Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

PRIVACY

Privacy:

_____

_____

Section-1

Prologue:

Many people consciously respect other people’s property yet sometimes fail to respect something even more important to a person which is his/her privacy. Every individual value his/her privacy. A private time with no one around gives you room to reflect on the most important issues in your life while private time with another helps to build close personal relationship with the one whom we choose to draw close to. To intrude in this is like stealing from someone or trespassing on the person’s domain. The right to privacy could refer to your right to be left alone or to your right not to share every detail with someone.

The most common retort against privacy advocates — by those in favour of ID checks, cameras, databases, data mining and other wholesale surveillance measures — is this line: “If you aren’t doing anything wrong, what do you have to hide?” Some clever answers: “If I’m not doing anything wrong, then you have no cause to watch me.” “Because the government gets to define what’s wrong, and they keep changing the definition.” “Because you might do something wrong with my information.” Basic problem with quips like these — as right as they are — is that they accept the premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong. It is not. Privacy is an inherent human right, and a requirement for maintaining the human condition with dignity and respect.

Cardinal Richelieu understood the value of surveillance when he famously said, “If one would give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest man, I would find something in them to have him hanged.” Watch someone long enough, and you’ll find something to arrest — or just blackmail — with. Privacy is important because without it, surveillance information will be abused: to peep, to sell to marketers and to spy on political enemies — whoever they happen to be at the time. Privacy protects us from abuses by those in power, even if we’re doing nothing wrong at the time of surveillance. A future in which privacy would face constant assault was so alien to the framers of the Constitution of many nations that it never occurred to them to call out privacy as an explicit right. Privacy was inherent to the nobility of their being and their cause.

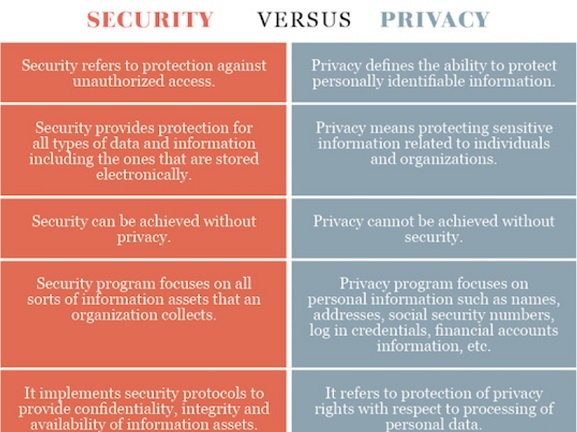

Of course, being watched in your own home was unreasonable. Watching at all was an act so unseemly as to be inconceivable among gentlemen in their day. You watched convicted criminals, not free citizens. You ruled your own home. It’s intrinsic to the concept of liberty. For if we are observed in all matters, we are constantly under threat of correction, judgment, criticism, even plagiarism of our own uniqueness. We become children, fettered under watchful eyes, constantly fearful that — either now or in the uncertain future — patterns we leave behind will be brought back to implicate us, by whatever authority that has now become focused upon our once-private and innocent acts. We lose our individuality, because everything we do is observable and recordable. Many people wrongly characterize the debate as “security versus privacy.” The real choice is liberty versus control. Tyranny, whether it arises under threat of foreign physical attack or under constant domestic authoritative scrutiny, is still tyranny. Liberty requires security without intrusion, security plus privacy.

Traditional concepts of privacy — our right to be left alone — and the basic principle that the content of our communications should remain confidential — are being challenged and eroded with advancements in digital technology. Similarly, the fundamental principle that individuals should be able to control when their personal data is collected by third parties and how it is used is nearly impossible to implement in a world where personal data is collected, created, used, processed, analysed, shared, transferred, copied, and stored in unprecedented ways and at an extraordinary speed and volume – without your consent! Many of our activities leave a trail of data. This includes phone records, credit card transactions, GPS in cars tracking our positions, mobile phones, smart wearable devices, smart toys, connected cars, drones, personal assistants like the Amazon echo, instant messaging, watching videos and browsing websites. In fact, online almost all activities leave a trail of data. There will be no opting out of this data-intensive world. Technology and sharing personal information have become indispensable to participation in modern society. Internet access and use of new digital technologies are necessary for employment, education, access to benefits, and full participation in economic and civic life. So, what happens to our personal data, identity, reputation, and privacy in this digital connected world? Unclear. Our privacy laws are based on antiquated notions of notice and choice, and are completely inadequate to address this rapid evolution in technology, computer science, and artificial intelligence.

_____

Abbreviations and synonyms:

PII = Personally Identifiable Information

ISP= Internet Service Providers

DPIA = Data Protection Impact Assessment

PIA = Privacy Impact Assessment

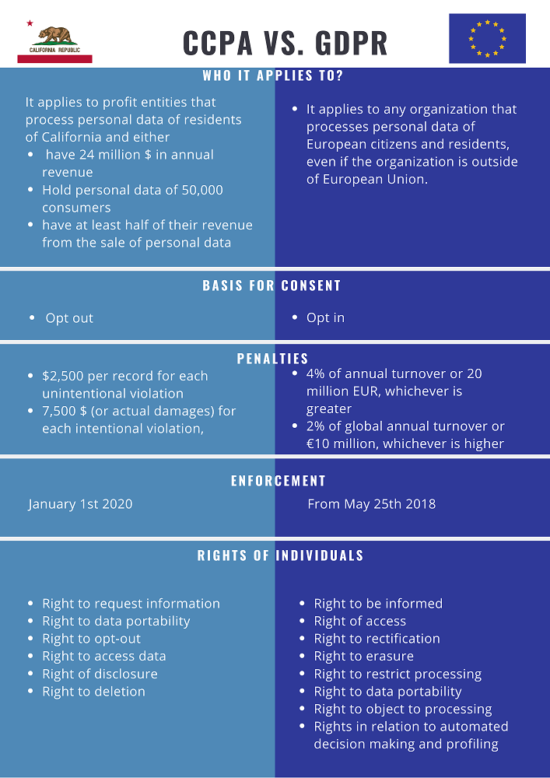

GDPR = General Data Protection Regulation

CCPA = California Consumer Privacy Act

HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

IP = internet protocol (responsible for establishing communications in most of our networks)

IP = intellectual property (protected in law by patents, copyright and trademarks)

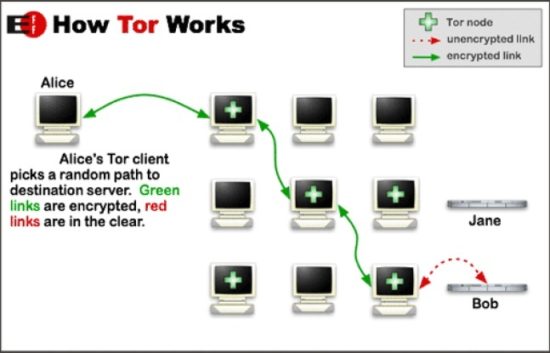

TOR = The Onion Router

VPN = Virtual Private Network

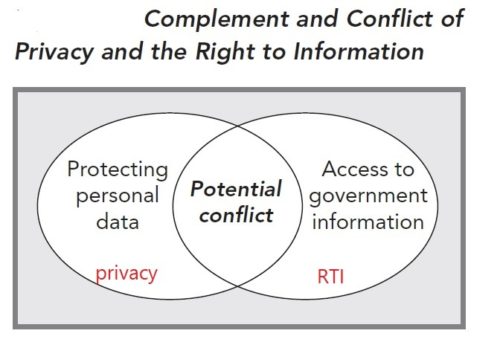

RTI = Right to Information

GSMA = Groupe Spéciale Mobile Association = Global System for Mobile Communications

VCC = Virtual Credit Card

NSA = National Security Agency

Right to be left alone = right to be let alone

_____

_____

Section-2

Introduction to privacy:

What is Privacy?

According to (Parent, 2012), “privacy is the condition of not having undocumented personal knowledge about one possessed by others.”

According to (Warren & Brandeis, 1890), “privacy consists of being let alone” (p.205).

According to (Sandel, 1989), “privacy is the right to engage in certain conduct without government restraint, the traditional version is the right to keep certain personal facts from public view” (p. 524)

According to (Garfinkel, 2000), “privacy is about self- possession, autonomy, and integrity” (p.4).

_

Privacy is a fundamental right, essential to autonomy and the protection of human dignity, serving as the foundation upon which many other human rights are built. Privacy enables us to create barriers and manage boundaries to protect ourselves from unwarranted interference in our lives, which allows us to negotiate who we are and how we want to interact with the world around us. Privacy helps us establish boundaries to limit who has access to our bodies, places and things, as well as our communications and our information. The rules that protect privacy give us the ability to assert our rights in the face of significant power imbalances. As a result, privacy is an essential way we seek to protect ourselves and society against arbitrary and unjustified use of power, by reducing what can be known about us and done to us, while protecting us from others who may wish to exert control. Privacy is essential to who we are as human beings, and we make decisions about it every single day. It gives us a space to be ourselves without judgement, allows us to think freely without discrimination, and is an important element of giving us control over who knows what about us.

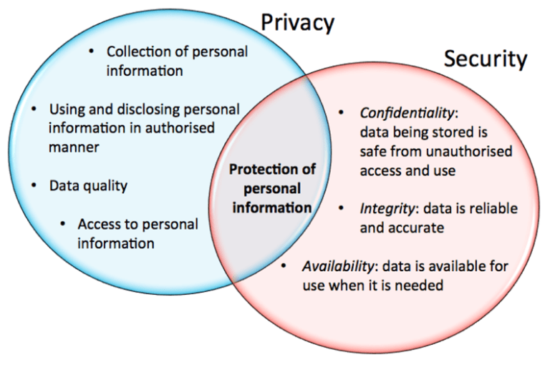

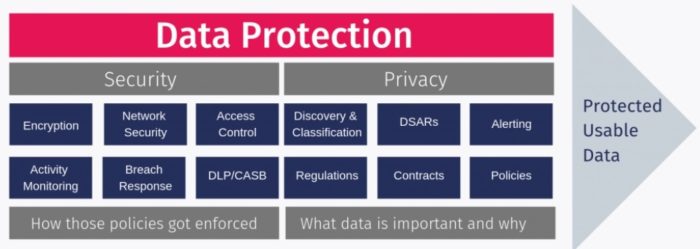

Privacy is freedom of an individual to be in solitude, withhold his/her private information and express oneself selectively. The boundaries and content of what is private or public differ among cultures and individuals, but still share common elements and constructs. When something is private to a person, it usually means that something is inherently special or sensitive to him/her. The domain of privacy partially overlaps security, which can include the concepts of appropriate use, as well as protection of information. Privacy may also take the form of bodily integrity and social dignity. Most cultures recognize the ability of individuals to withhold certain parts of their personal information from wider society, such as closing the door to one’s home.

Privacy as per article no. 12 of Universal Human Rights Declaration (UHRD, 1948):

‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.’

Thus, we find privacy is anything which if lost can result in ruining a person’s reputation, honour, relation, intellectual possession and the like. Life is not merely eat, sleep and sex, it is much more, also demands non material entities like environment, love, acceptance, happiness and privacy as well.

____

The term “privacy” is used frequently in ordinary language as well as in philosophical, political and legal discussions, yet there is no single definition or analysis or meaning of the term. The concept of privacy has broad historical roots in sociological and anthropological discussions about how extensively it is valued and preserved in various cultures. Moreover, the concept has historical origins in well-known philosophical discussions, most notably Aristotle’s distinction between the public sphere of political activity and the private sphere associated with family and domestic life. Yet historical use of the term is not uniform, and there remains confusion over the meaning, value and scope of the concept of privacy.

Early treatises on privacy appeared with the development of privacy protection in American law from the 1890s onward, and privacy protection was justified largely on moral grounds. This literature helps distinguish descriptive accounts of privacy, describing what is in fact protected as private, from normative accounts of privacy defending its value and the extent to which it should be protected. In these discussions some treat privacy as an interest with moral value, while others refer to it as a moral or legal right that ought to be protected by society or the law. Clearly one can be insensitive to another’s privacy interests without violating any right to privacy, if there is one.

There are several sceptical and critical accounts of privacy. According to one well known argument there is no right to privacy and there is nothing special about privacy, because any interest protected as private can be equally well explained and protected by other interests or rights, most notably rights to property and bodily security (Thomson, 1975). Other critiques argue that privacy interests are not distinctive because the personal interests they protect are economically inefficient (Posner, 1981) or that they are not grounded in any adequate legal doctrine (Bork, 1990). Finally, there is the feminist critique of privacy, that granting special status to privacy is detrimental to women and others because it is used as a shield to dominate and control them, silence them, and cover up abuse (MacKinnon, 1989).

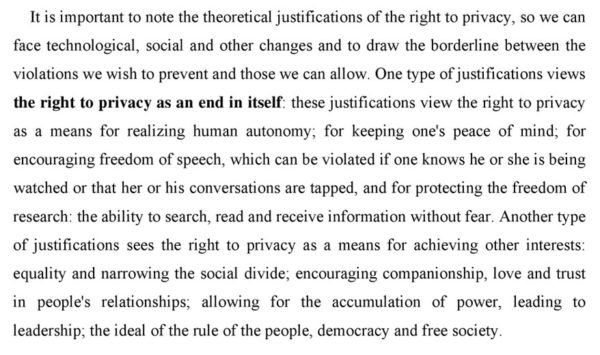

Nevertheless, most theorists take the view that privacy is a meaningful and valuable concept. Philosophical debates concerning definitions of privacy became prominent in the second half of the twentieth century, and are deeply affected by the development of privacy protection in the law. Some defend privacy as focusing on control over information about oneself (Parent, 1983), while others defend it as a broader concept required for human dignity (Bloustein, 1964), or crucial for intimacy (Gerstein, 1978; Inness, 1992). Other commentators defend privacy as necessary for the development of varied and meaningful interpersonal relationships (Fried, 1970, Rachels, 1975), or as the value that accords us the ability to control the access others have to us (Gavison, 1980; Allen, 1988; Moore, 2003), or as a set of norms necessary not only to control access but also to enhance personal expression and choice (Schoeman, 1992), or some combination of these (DeCew, 1997). Discussion of the concept is complicated by the fact that privacy appears to be something we value to provide a sphere within which we can be free from interference by others, and yet it also appears to function negatively, as the cloak under which one can hide domination, degradation, or physical harm to women and others.

_____

Privacy is a fundamental human right. It protects human dignity and other values such as freedom of association and freedom of speech. It has become one of the most important human rights of the modern age. Privacy is recognized around the world in different regions and cultures. It is protected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and in many other international and right of privacy in its constitution. At a minimum, these provisions include rights of inviolability of the home and secrecy of communications. In many of the countries where privacy is not specifically recognized in the constitution, the courts have found that right in other provisions. In the United States, the concept of privacy has evolved since it was first articulated by Justice Brandeis in 1898. His definition of privacy – “The right to be let alone” (Brandeis and Warren, 1890) – has been influential for nearly a century. In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the proliferation of information technology (and concurrent developments in the law of reproductive and sexual liberties) prompted further and more sophisticated legal inquiry into the meaning of privacy. Justice Brandeis’s vision of being “let alone” no longer suffices to define the concept of privacy in today’s digital environment, where personal information can be transported and distributed around the world in seconds. With the growth and development of new technological advancements, society and government also recognized its importance. The surveillance potential of powerful computer systems prompted demands for specific rules governing the collection and handling of personal information.

The genesis of modern legislation in this area can be traced to the first data protection law enacted in Germany in 1970. This was followed by national laws in Sweden (1973), the United States (1974), Germany (1977), and France (1978). At the end of 2000, ideas about privacy became more complex. It reflected, the rapid and remarkable advances in computers that have made storage, manipulation, and sharing of data at unprecedented rate.

_____

Many philosophers have examined the moral foundations of privacy interests. Some hold that the obligation to protect privacy is ultimately based on other, more fundamental moral principles such as the right to liberty or autonomy or the duty to not harm others. For example, breaching medical privacy can be regarded as unethical because it can cause harm such as loss of employment, discrimination, legal liability, or embarrassment to the person. Breaching privacy may be unethical even if it does not cause any harm because it violates a person’s right to control the disclosure of private information. Watching someone undress without permission invades physical privacy; even if it does not cause harm to the person, it violates his or her right to control access to his or her body. Others hold that violations of privacy are wrong because they undermine intimacy, which is necessary for the formation of meaningful human relationships. People develop close relationships by sharing private information, secret dreams and desires, and physical space. Because people cannot form these close relationships unless they have some expectation that their privacy will be protected, society needs laws and ethical rules to protect privacy.

______

Privacy is hitting the headlines more than ever. As computer users are asked to change their passwords again and again in the wake of exploits like Heartbleed and Shellshock, they’re becoming aware of the vulnerability of their online data — a susceptibility that was recently verified by scores of celebrities who had their most intimate photographs stolen.

Any of us could have our privacy violated at any time… but what does that mean exactly?

What privacy means varies between Europe and the US, between libertarians and public figures, between the developed world and developing countries, between women and men.

However, before you can define privacy, you first have to define its opposite number: what’s public. merriam-webster.com’s first definition of “public” includes two different descriptions that are somewhat contradictory. The first is “exposed to general view: open” and the second is “well-known; prominent”.

These definitions are at odds with each other because it’s easy for something to be exposed to view without it being prominent. In fact, that defines a lot of our everyday life. If you have a conversation with a friend in a restaurant or if you do something in your living room with the curtains open or if you write a message for friends on Facebook, you presume that what you’re doing will not be well-known, but it certainly could be open to general view.

So, is it public or is it private?

It turns out that this is a very old question. When talking about recent celebrity photo thefts, Kyle Chayka highlighted the early 20th-century case of Gabrielle Darley Melvin, an ex-prostitute who had been acquitted of murderer. After settling quietly into marriage, Melvin found herself the subject of an unauthorized movie that ripped apart the fabric of her new life. Melvin sued the makers of the film but lost. She was told in the 1931 decision Melvin v. Reid: “When the incidents of a life are so public as to be spread upon a public record they come within the knowledge and into the possession of the public and cease to be private.” So the Supreme Court of Los Angeles had one answer for what was public and what was private.

Melvin’s case was one where public events had clearly entered the public consciousness. However today, more and more of what people once thought of as private is also escaping into the public sphere — and we’re often surprised by it. That’s because we think that private means secret, and it doesn’t; it just means something that isn’t public.

Anil Dash recently discussed this on Medium and he highlighted a few reasons that privacy is rapidly sliding down this slippery slope of publication.

First, companies have financial incentives for making things “well-known” or “prominent”. The 24-hour news cycle is forcing media to report everything, so they’re mobbing celebrities and publishing conversations from Facebook or Twitter that people consider private. Meanwhile, an increasing number of tech companies are mining deep ores of data and selling them to the highest bidder; the more information that they can find, the more they can sell.

Second, technology is making it ridiculously easy to take those situations that are considered “private” despite being “exposed to general view” and making them public. It’s easier than ever to record a conversation, or steal data, or photograph or film through a window, or overhear a discussion. Some of these methods are legal, some aren’t, but they’re all happening — and they seem to be becoming more frequent.

The problem is big enough that governments are passing laws on the topic. In May 2014, the European Court of Justice decreed that people had a “Right to Be Forgotten”: they should be able to remove information about themselves from the public sphere if it’s no longer relevant, making it private once more. Whether this was a good decision remains to be seen, as it’s already resulted in the removal of information that clearly is relevant to the public sphere. In addition, it’s very much at odds with the laws and rights of the United States, especially the free speech clause of the First Amendment. As Jeffrey Toobin said in a New Yorker article: “In Europe, the right to privacy trumps freedom of speech; the reverse is true in the United States.” However right to be forgotten is distinct from the right to privacy.

All of this means that the line between public and private remains as fuzzy as ever.

We have a deep need for the public world: both to be a part of it and to share ourselves with it. However, we also have a deep need for privacy: to keep our information, our households, our activities, and our intimate connections free from general view. In the modern world, drawing the line between these two poles is something that every single person has to consider and manage.

That’s why it’s important that each individual define their own privacy needs — so that they can fight for the kinds of privacy that are important to them.

______

______

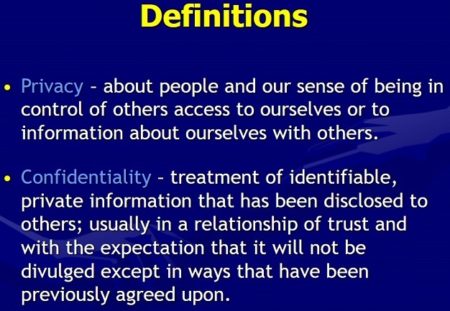

Definitions of privacy:

Of all the human rights in the international catalogue, privacy is perhaps the most difficult to define and circumscribe. Privacy has roots deep in history. The Bible has numerous references to privacy. There was also substantive protection of privacy in early Hebrew culture, Classical Greece and ancient China. These protections mostly focused on the right to solitude. Definitions of privacy vary widely according to context and environment. In many countries, the concept has been fused with Data Protection, which interprets privacy in terms of management of personal information. Outside this rather strict context, privacy protection is frequently seen as a way of drawing the line at how far society can intrude into a person’s affairs.

_

Privacy has deep historical roots (reviewed by Pritts, 2008; Westin, 1967), but because of its complexity, privacy has proven difficult to define and has been the subject of extensive, and often heated, debate by philosophers, sociologists, and legal scholars. The term “privacy” is used frequently, yet there is no universally accepted definition of the term, and confusion persists over the meaning, value, and scope of the concept of privacy. At its core, privacy is experienced on a personal level and often means different things to different people (reviewed by Lowrance, 1997; Pritts, 2008). In modern society, the term is used to denote different, but overlapping, concepts such as the right to bodily integrity or to be free from intrusive searches or surveillance. The concept of privacy is also context specific, and acquires a different meaning depending on the stated reasons for the information being gathered, the intentions of the parties involved, as well as the politics, convention and cultural expectations (Nissenbaum, 2004; NRC, 2007b).

_

In the 1890s, future United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis articulated a concept of privacy that urged that it was the individual’s “right to be left alone.” Brandeis argued that privacy was the most cherished of freedoms in a democracy, and he was concerned that it should be reflected in the Constitution.

Robert Ellis Smith, editor of the Privacy Journal, defined privacy as “the desire by each of us for physical space where we can be free of interruption, intrusion, embarrassment, or accountability and the attempt to control the time and manner of disclosures of personal information about ourselves.”

According to Edward Bloustein, privacy is an interest of the human personality. It protects the inviolate personality, the individual’s independence, dignity and integrity.

According to Ruth Gavison, there are three elements in privacy: secrecy, anonymity and solitude. It is a state which can be lost, whether through the choice of the person in that state or through the action of another person.

The Calcutt Committee in the United Kingdom said that, “nowhere have we found a wholly satisfactory statutory definition of privacy.” But the committee was satisfied that it would be possible to define it legally and adopted this definition in its first report on privacy: The right of the individual to be protected against intrusion into his personal life or affairs, or those of his family, by direct physical means or by publication of information. The Preamble to the Australian Privacy Charter provides that, “A free and democratic society requires respect for the autonomy of individuals, and limits on the power of both state and private organizations to intrude on that autonomy…Privacy is a key value which underpins human dignity and other key values such as freedom of association and freedom of speech…Privacy is a basic human right and the reasonable expectation of every person.” Autonomy means the ability to make our own life decision free from any force. Some authors refer to privacy as “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.”

_

The Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation (referred to as Common Criteria or CC) is an international standard (ISO/IEC 15408) for computer security certification. According with the CC standard, privacy involves “user protection against discovery and misuse of identity by other users”. In addition, the CC standard defines the following requirements in order to guarantee privacy:

- Anonymity

- Pseudonymity

- Unlinkability

- Unobservability

Thus, we consider the definition of privacy as a framework of requirements that prevents the discovery and identity of the user.

Anonymity:

Anonymity is intrinsically present in the concept of privacy. Nevertheless, anonymity refers exclusively to the matters related to the identity. The CC standard defines “anonymity ensures that a user may use a resource or service without disclosing the user’s identity. The requirements for anonymity provide protection of the user identity. Anonymity is not intended to protect the subject identity. […] Anonymity requires that other users or subjects are unable to determine the identity of a user bound to a subject or operation.”

Privacy is when nobody is aware of what you are doing but potentially they know your identity. Privacy relates to content. If you send an encrypted email to a friend so only the two of you can open it, this is private. It is not public. Anonymity is when nobody knows who you are but potentially they know what you are doing.

Pseudonymity:

The use of anonymity techniques can protect the user from revealing their real identity. Most of the time there is a technological requirement necessary to interact with an entity, thus, such entity requires to have some kind of identity. The CC standard claims pseudonymity ensures that a user may use a resource or service without disclosing its user identity, but can still be accountable for that use.

Unlinkability:

In order to guarantee a protection of the user’s identity, there is a need for unlinkability of the user’s activities within a particular context. This involves the lack of information to distinguish if the activities performed by the user are related or not.

Unobservability:

The CC standard refers to this concept as “unobservability, requires that users and/or subjects cannot determine whether an operation is being performed.”. Other authors claim that unobservability should be differentiated from the undetectability. The reasoning behind this, claims that something can be unobservable, but can still be detected.

______

In spite of the several attempts that have been made to define privacy; no universal definition of privacy could be created. Despite the fact that the claim for privacy in universal, its concrete form differs according to the prevailing societal characteristics, the economic and cultural environment. It means that privacy must be reinterpreted in the light of the current era and be examined in the current context.

There are several factors that affect what people consider private. There are huge differences between particular societies and cultures, or scientific development can also lead to a different, urging need for ensuring the protection of privacy. It depends on the concrete situation, on the context: sharing the same information in different situations might be considered private differently. American law professor Alan Westin established three levels that affect privacy norms: the political, the socio-cultural and the personal level. The individual also plays a central role: privacy can be understood as a quasi “aura” around the individual, which constitutes the limit between him/her and the outside world. The limits of this aura change from context to context and from individual to individual, so from all this individualized and changing context an average standard must be found and this standard can be legally protected. Besides this always changing context, numerous attempts to define privacy have been made during the last 120 years. However, there is a problem with all these definitions, which Daniel Solove explained in one of his articles: their scope is either too narrow or too broad. He emphasizes that it does not mean that these concepts lack of merit, the problem is that these authors use a traditional method of conceptualizing privacy, and as a result their definitions only highlight either some aspects of privacy, or they are too broad and do not give an exact view on the elements of privacy. He created six categories for these definitions according to which privacy is (1) the right to be let alone, (2) limited access to the self, (3) secrecy, (4) control of personal information, (5) personhood and (6) intimacy.

As already presented, Warren and Brandeis defined privacy as “the right to be let alone”. According to Israeli law professor Ruth Gavison “our interest in privacy […] is related to our concern over our accessibility to others: the extent to which we are known to others, the extent to which others have physical access to us, and the extent to which we are the subject of others’ attention.” American jurist and economist Richard Posner avoid giving a definition but states “that one aspect of privacy is the withholding or concealment of information.” From among the authors who consider privacy as a control over personal information, Alan Westin and American professor Charles Fried must be mentioned. Westin defined privacy as “the claim of an individual to determine what information about himself or herself should be known to others” while Fried stated that „privacy […] is the control we have over information about ourselves.” American Edward Bloustein argued that intrusion into privacy has a close connection with personhood, individuality and human dignity. American professor Tom Gerety understands privacy as “the control over or the autonomy of the intimacies of personal identity”. Máté Dániel Szabó, Hungarian jurist, argued that “privacy is the right of the individual to decide about himself/herself”. As all these definitions state something very important about what we should consider private, it is an extremely hard task to attempt to create a uniform definition of privacy.

_______

_______

What is personally identifiable information (PII)?

Personally identifiable information (PII) is any data that can be used to identify a specific individual. Social Security numbers, mailing or email address, and phone numbers have most commonly been considered PII, but technology has expanded the scope of PII considerably. It can include an IP address, login IDs, social media posts, or digital images. Geolocation, biometric, and behavioral data can also be classified as PII.

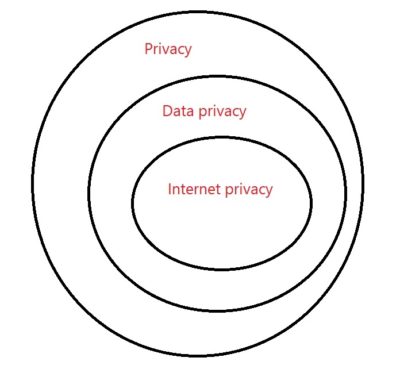

Internet privacy involves the right or mandate of personal privacy concerning the storing, repurposing, provision to third parties, and displaying of information pertaining to oneself via the Internet. Internet privacy is a subset of data privacy. Privacy concerns have been articulated from the beginnings of large-scale computer sharing. It has been suggested that the “appeal of online services is to broadcast personal information on purpose.”

_

_

With all around technological invasion in all sort of life activities, information privacy is becoming more complex by every passing minute as more and more data is being collected, transferred, exchanged and analyzed for positive and negative reasons. As the technology gets more powerful and invasive it becomes more of a sensitive issue as it tries to blur the line between private and public. Even the business houses in the field are facing an uphill task to protect the personal information of the customers safe. As a result, privacy has become the most delicate consumer protection issue in this age of information, which otherwise is a human right at first place.

The former US Homeland Security secretary, Michael Chertoff, has been in the news of late, discussing cybersecurity and his new book ‘Exploding Data’. His opinion gets fairly scary as he intimates most of our personal/corporate data is out there already, and we all have no idea who already has it and what they intend to do with it. Data has become the “new domain of warfare,” or at least part of the toolbox for waging war. So, is stealing data or spying considered warfare? Chertoff says no, “but if you destroy things and kill people with it, that’s warfare.” He further points to the public and business fascination and reliance upon social media as an obvious data giveaway. Chertoff warns of our cell phone usage as an immediate and direct funnel of personal, and private, information. “We’re opening ourselves up and freely giving away our data, even “Locational Data…our Digital Exhaust,” as he puts it. Loyalty cards at the grocery store, credit cards, iWallet’s, ride services and the like are other examples, and Chertoff explains that we give it away easily in the name of convenience and consumerism.

______

Control over information:

Control over one’s personal information is the concept that “privacy is the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.” Generally, a person who has consensually formed an interpersonal relationship with another person is not considered “protected” by privacy rights with respect to the person they are in the relationship with. Charles Fried said that Privacy is not simply an absence of information about us in the minds of others; rather it is the control we have over information about ourselves. Nevertheless, in the era of big data, control over information is under pressure.

______

Surveillance:

Surveillance is the systematic investigation or monitoring of the actions or communications of one or more persons. The primary purpose of surveillance is generally to collect information about the individuals concerned, their activities, or their associates. There may be a secondary intention to deter a whole population from undertaking some kinds of activity.

Two separate classes of surveillance are usefully identified:

-1, Personal Surveillance is the surveillance of an identified person. In general, a specific reason exists for the investigation or monitoring. It may also, however, be applied as a means of deterrence against particular actions by the person, or repression of the person’s behaviour.

-2. Mass Surveillance is the surveillance of groups of people, usually large groups. In general, the reason for investigation or monitoring is to identify individuals who belong to some particular class of interest to the surveillance organization. It may also, however, be used for its deterrent effects.

The basic form, physical surveillance, comprises watching (visual surveillance) and listening (aural surveillance). Monitoring may be undertaken remotely in space, with the aid of image- amplification devices like field glasses, infrared binoculars, light amplifiers, and satellite cameras, and sound- amplification devices like directional microphones; and remotely in time, with the aid of image and sound- recording devices.

In addition to physical surveillance, several kinds of communications surveillance are practised, including mail covers and telephone interception.

The popular term electronic surveillance refers to both augmentations to physical surveillance (such as directional microphones and audio bugs) and to communications surveillance, particularly telephone taps.

These forms of direct surveillance are commonly augmented by the collection of data from interviews with informants (such as neighbours, employers, workmates, and bank managers). As the volume of information collected and maintained has increased, the record collections of organizations have become an increasingly important source. These are often referred to as ‘personal data systems’. This has given rise to an additional form of surveillance:

Data Surveillance (or Dataveillance) is the systematic use of personal data systems in the investigation or monitoring of the actions or communications of one or more persons. Dataveillance is significantly less expensive than physical and electronic surveillance, because it can be automated. As a result, the economic constraints on surveillance are diminished, and more individuals, and larger populations, are capable of being monitored.

Like surveillance more generally, dataveillance is of two kinds:

-1. Personal Dataveillance is the systematic use of personal data systems in the investigation or monitoring of the actions or communications of an identified person. In general, a specific reason exists for the investigation or monitoring of an identified individual. It may also, however, be applied as a means of deterrence against particular actions by the person, or repression of the person’s behaviour.

-2. Mass Dataveillance is the systematic use of personal data systems in the investigation or monitoring of the actions or communications of groups of people. In general, the reason for investigation or monitoring is to identify individuals who belong to some particular class of interest to the surveillance organization. It may also, however, be used for its deterrent effects.

Dataveillance comprises a wide range of techniques. These include:

-1. Front- End Verification. This is the cross-checking of data in an application form, against data from other personal data systems, in order to facilitate the processing of a transaction.

-2. Computer Matching. This is the expropriation of data maintained by two or more personal data systems, in order to merge previously separate data about large numbers of individuals.

-3. Profiling. This is a technique whereby a set of characteristics of a particular class of person is inferred from past experience, and data-holdings are then searched for individuals with a close fit to that set of characteristics.

-4. Data Trail This is a succession of identified transactions, which reflect real-world events in which a person has participated.

______

How do surveillance and privacy relate?

They both are about the control of information—in one case as discovery, in the other as protection. At the most basic level, surveillance is a way of accessing data. Surveillance, implies an agent who accesses (whether through discovery tools, rules or physical/logistical settings) personal data. Privacy, in contrast, involves a subject who restricts access to personal data through the same means. In popular and academic dialogue surveillance is often wrongly seen to be the opposite of privacy and, in simplistic dramaturgy, the former is seen as bad and the latter good. For example, social psychologist Kelvin (Kelvin 1973) emphasized privacy as a nullification mechanism for surveillance. But Kelvin’s assertion needs to be seen as only one of four basic empirical connections between privacy and surveillance. Surveillance is not necessarily the dark side of the social dimension of privacy.

-Yes, privacy (or better actions taken to restrict access to all or only to insiders) may serve to nullify surveillance. Familiar examples are encryption, whispering, and disguises.

But

-Surveillance may serve to protect privacy. Examples include biometric identification and audit trails.

-Privacy may serve to protect surveillance. Consider undercover police who use various fronts and false identification to protect their real identity and activities.

-Surveillance may serve to nullify privacy as Kelvin claims. (Big data, night vision video cameras, drugs tests)

_

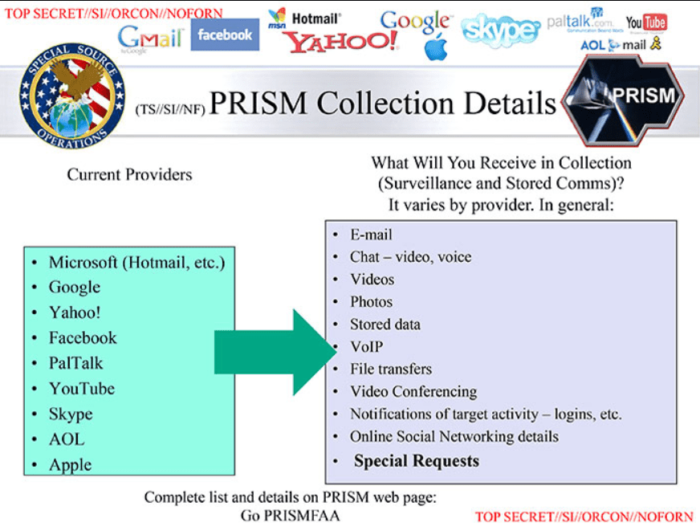

Government mass surveillance:

Over the past decade, rapid advancements in communications technology and new understandings of global security and cybersecurity have motivated governments to eschew the traditional limitations of lawfulness, necessity and proportionality on surveillance. It is perceived that reviewing every communication is necessary to understand all aspects of potential threats to national security, as each message could be the proverbial needle in the digital haystack. This has led to the development of mass surveillance, also known as bulk collection or bulk interception, which captures extensive amounts of data from the undersea fibre-optic cables that carry most of the world’s data.

Mass surveillance programmes form a key part of many national security apparatuses and can be purchased on the private market, including by oppressive regimes. Mass surveillance is often neither lawful nor acknowledged by national authorities, although a recent wave of legal reform aims to grant the practice greater legitimacy. It may be conducted without the knowledge and assistance of ICT companies, who typically own and manage the channels by which information is communicated, although telecommunications companies and Internet service providers are in many instances informed of, asked to cooperate with, or compelled to facilitate government programmes.

Mass surveillance not only compromises the very essence of privacy, but also jeopardizes the enjoyment of other human rights such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly and association. This can undermine democratic movements, impede innovation, and leave citizens vulnerable to the abuse of power.

_

In both academic and popular discussion privacy is too often justified as a value because of what it is presumed to do for individuals. But it can also be a positive social value because of what it does for the group. An additional point (neglected by some of privacy’s more strident supporters) is that it can also be an anti-social value tied to private property and modernization.

In contrast, surveillance is too often criticized for what it is presumed to do for more powerful groups (whether government or corporations) relative to the individual. But it can also be a pro-social value. Just as privacy can support the dignity and freedom to act of the person, surveillance can protect the integrity and independence of groups vital to a pluralistic democratic society and it can offer protection to individuals, whether for the dependent such as children and the sick, or to those who like clean water and industrial safety and do not want their precious liberties destroyed by enemies. Surveillance, like privacy, can be good for the individual and for the society, but like privacy it can also have negative consequences for both.

______

Scope of privacy:

Professor Roger Clarke suggests that the importance of privacy has psychological, sociological, economic and political dimensions.

-1. Psychologically, people need private space. This applies in public as well as behind closed doors and drawn curtains …

-2. Sociologically, people need to be free to behave, and to associate with others, subject to broad social mores, but without the continual threat of being observed …

-3. Economically, people need to be free to innovate …

-4. Politically, people need to be free to think, and argue, and act. Surveillance chills behaviour and speech, and threatens democracy.

In general, privacy is a right to be free from secret surveillance and to determine whether, when, how, and to whom, one’s personal or organizational information is to be revealed.

______

States of privacy:

Alan Westin defined four states—or experiences—of privacy: solitude, intimacy, anonymity, and reserve. Solitude is a physical separation from others. Intimacy is a “close, relaxed, and frank relationship between two or more individuals” that results from the seclusion of a pair or small group of individuals. Anonymity is the “desire of individuals for times of ‘public privacy.'” Lastly, reserve is the “creation of a psychological barrier against unwanted intrusion”; this creation of a psychological barrier requires others to respect an individual’s need or desire to restrict communication of information concerning himself or herself.

In addition to the psychological barrier of reserve, Kirsty Hughes identified three more kinds of privacy barriers: physical, behavioral, and normative. Physical barriers, such as walls and doors, prevent others from accessing and experiencing the individual. Behavioral barriers communicate to others—verbally, through language, or non-verbally, through personal space, body language, or clothing—that an individual does not want them to access or experience him or her. Lastly, normative barriers, such as laws and social norms, restrain others from attempting to access or experience an individual.

______

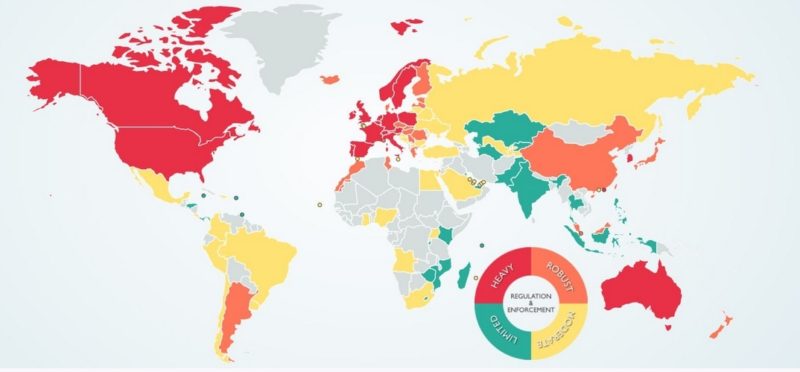

Privacy is a fundamental human right recognized in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and in many other international and regional treaties. Privacy underpins human dignity and other key values such as freedom of association and freedom of speech. It has become one of the most important human rights issues of the modern age. Many countries in the world recognizes a right of privacy explicitly in their Constitution. At a minimum, these provisions include rights of inviolability of the home and secrecy of communications. Most recently-written Constitutions such as South Africa’s and Hungary’s include specific rights to access and control one’s personal information. In many of the countries where privacy is not explicitly recognized in the Constitution, such as the United States, Ireland and India, the courts have found that right in other provisions. In many countries, international agreements that recognize privacy rights such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the European Convention on Human Rights have been adopted into law.

Reasons for Adopting Comprehensive Privacy Laws:

There are three major reasons for the movement towards comprehensive privacy and data protection laws. Many countries are adopting these laws for one or more reasons.

- To remedy past injustices. Many countries, especially in Central Europe, South America and South Africa, are adopting laws to remedy privacy violations that occurred under previous authoritarian regimes.

- To promote electronic commerce. Many countries, especially in Asia, but also Canada, have developed or are currently developing laws in an effort to promote electronic commerce. These countries recognize consumers are uneasy with their personal information being sent worldwide. Privacy laws are being introduced as part of a package of laws intended to facilitate electronic commerce by setting up uniform rules.

- To ensure laws are consistent with Pan-European laws. Most countries in Central and Eastern Europe are adopting new laws based on the Council of Europe Convention and the European Union Data Protection Directive. Many of these countries hope to join the European Union in the near future. Countries in other regions, such as Canada, are adopting new laws to ensure that trade will not be affected by the requirements of the EU Directive.

Continuing Problems:

Even with the adoption of legal and other protections, violations of privacy remain a concern. In many countries, laws have not kept up with the technology, leaving significant gaps in protections. In other countries, law enforcement and intelligence agencies have been given significant exemptions. Finally, in the absence of adequate oversight and enforcement, the mere presence of a law may not provide adequate protection.

There are widespread violations of laws relating to surveillance of communications, even in the most democratic of countries. The U.S. State Department’s annual review of human rights violations finds that over 90 countries engage in illegally monitoring the communications of political opponents, human rights workers, journalists and labor organizers. In France, a government commission estimated in 1996 that there were over 100,000 wiretaps conducted by private parties, many on behalf of government agencies. In Japan, police were recently fined 2.5 million yen for illegally wiretapping members of the Communist party. Police services, even in countries with strong privacy laws, still maintain extensive files on citizens not accused or even suspected of any crime. There are investigations in Sweden and Norway, two countries with the longest history of privacy protection for police files. Companies regularly flaunt the laws, collecting and disseminating personal information. In the United States, even with the long-standing existence of a law on consumer credit information, companies still make extensive use of such information for marketing purposes.

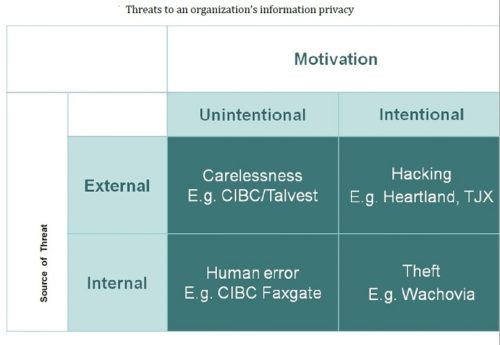

Threats to privacy:

The increasing sophistication of information technology with its capacity to collect, analyze and disseminate information on individuals has introduced a sense of urgency to the demand for legislation. Furthermore, new developments in medical research and care, telecommunications, advanced transportation systems and financial transfers have dramatically increased the level of information generated by each individual. Computers linked together by high speed networks with advanced processing systems can create comprehensive dossiers on any person without the need for a single central computer system. New technologies developed by the defense industry are spreading into law enforcement, civilian agencies, and private companies.

According to opinion polls, concern over privacy violations is now greater than at any time in recent history. Uniformly, populations throughout the world express fears about encroachment on privacy, prompting an unprecedented number of nations to pass laws which specifically protect the privacy of their citizens. Human rights groups are concerned that much of this technology is being exported to developing countries which lack adequate protections. Currently, there are few barriers to the trade in surveillance technologies.

It is now common wisdom that the power, capacity and speed of information technology is accelerating rapidly. The extent of privacy invasion — or certainly the potential to invade privacy — increases correspondingly.

Beyond these obvious aspects of capacity and cost, there are a number of important trends that contribute to privacy invasion:

-1. Globalization removes geographical limitations to the flow of data. The development of the Internet is perhaps the best-known example of a global technology.

-2. Convergence is leading to the elimination of technological barriers between systems. Modern information systems are increasingly interoperable with other systems, and can mutually exchange and process different forms of data.

-3. Multi-media fuses many forms of transmission and expression of data and images so that information gathered in a certain form can be easily translated into other forms.

The macro-trends outlined above have definite effect on surveillance in various nations.

_______

_______

Various kinds of privacy:

Different authors have classified privacy differently. Here are some examples.

_

It has been suggested that privacy can be divided into a number of separate, but related, concepts:

-1. Information privacy, which involves the establishment of rules governing the collection and handling of personal data such as credit information, and medical and government records. It is also known as ‘data protection’;

-2. Bodily privacy, which concerns the protection of people’s physical selves against invasive procedures such as genetic tests, drug testing and cavity searches;

-3. Privacy of communications, which covers the security and privacy of mail, telephones, e-mail and other forms of communication; and

-4. Territorial privacy, which concerns the setting of limits on intrusion into the domestic and other environments such as the workplace or public space. This includes searches, video surveillance and ID checks.

_

Clarke’s four categories of privacy:

Roger Clarke’s human-centred approach to defining categories of privacy does assist in outlining what specific elements of privacy are important and must be protected.

Clarke’s four categories of privacy, outlined in 1997, include privacy of the person, privacy of personal data, privacy of personal behaviour and privacy of personal communication.

Privacy of the person has also been referred to as “bodily privacy” and is specifically related to the integrity of a person’s body. It would include protections against physical intrusions, including torture, medical treatment, the “compulsory provision of samples of body fluids and body tissue” and imperatives to submit to biometric measurement. For Clarke, privacy of the person is thread through many medical and surveillance technologies and practices. Privacy of personal behaviour includes a protection against the disclosure of sensitive personal matters such as religious practices, sexual practices or political activities. Clarke notes that there is a space element included within privacy of personal behaviour, where people have a right to private space to carry out particular activities, as well as a right to be free from systematic monitoring in public space. Privacy of personal communication refers to a restriction on monitoring telephone, e-mail and virtual communications as well as face-to-face communications through hidden microphones. Finally, privacy of personal data refers to data protection issues. Clarke adds that, with the close coupling that has occurred between computing and communications, particularly since the 1980s, the last two aspects have become closely linked, and are commonly referred to as “information privacy”.

Four to Seven categories of privacy:

Despite the utility of these four categories, recent technological advances have meant that they are no longer adequate to capture the range of potential privacy issues which must be addressed. Specifically, technologies such as whole body imaging scanners, RFID-enabled travel documents, unmanned aerial vehicles, second-generation DNA sequencing technologies, human enhancement technologies and second-generation biometrics raise additional privacy issues, which necessitate an expansion of Clarke’s four categories. These new and emerging technologies argue for an expansion to seven different types of privacy, including privacy of the person, privacy of behaviour and action, privacy of personal communication, privacy of data and image, privacy of thoughts and feelings, privacy of location and space and privacy of association (including group privacy).

_______

_______

Another way to classify privacy is privacy of space, body, information and choice.

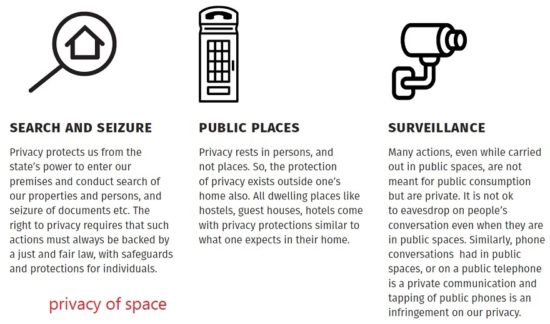

Privacy of space:

Privacy of space protects private spaces or zones where one has a reasonable expectation of privacy from outside interference or intrusion.

The right to privacy initially focused on protecting “private” spaces. These included spaces such as the home, from state interference. This drew from the belief that “a person’s home is their castle”. However, this idea of privacy is not limited simply to a person’s home. Privacy rests in ‘person’ and not in ‘places’. Therefore, even outside one’s home, other spaces could also acquire the character of private spaces, and even public spaces can afford a degree of privacy.

_

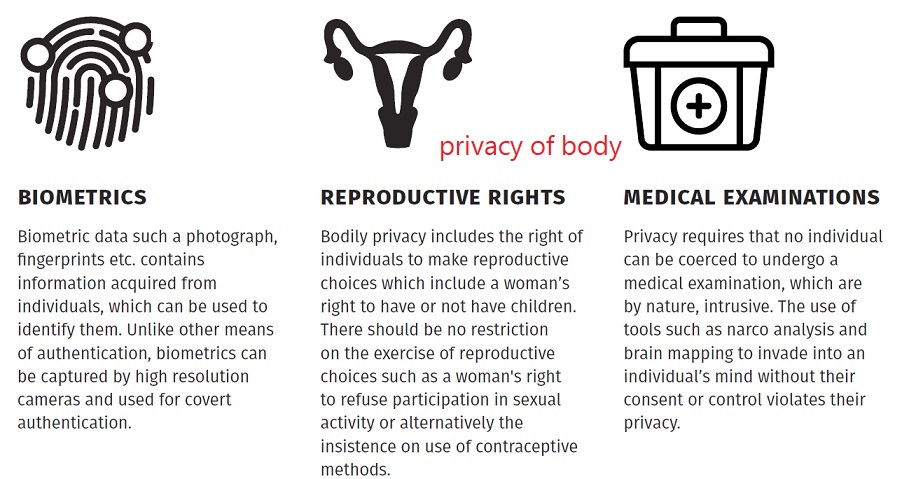

Privacy of body:

Privacy of body protects bodily integrity, and acts against physical and psychological intrusions into our bodies and bodily spaces.

Privacy of body is fundamental to our understanding of our bodies as private. The understanding of where bodily privacy extends is contextual and our boundaries may start at our skin, or the point where we can feel breath, or even till the other side of the room. It is the point where we feel touched and physically affected by another person. Similarly, intrusions into our psychological space without consent and control violate our bodily privacy.

_

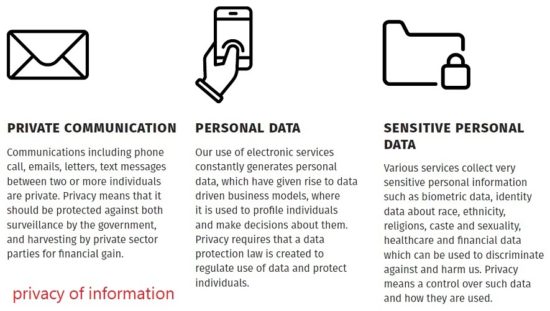

Privacy of information:

Privacy of information is our right to meaningful control over the sharing & use of information about ourselves without coercion or compulsion.

In the age of Big Data, the collection and analysis of personal data has tremendous economic value. However, these economic interests should not be pursued at the expense of personal privacy. Similarly, modern technology provides excessive opportunities to governments to monitor and surveil the lives of citizens. Informed Consent and meaningful choice while sharing information about ourselves is central to the idea of informational privacy.

_

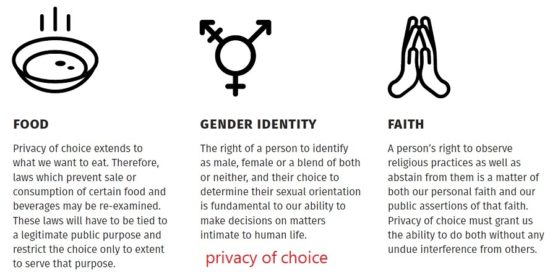

Privacy of choice:

Privacy of choice means our right to make choices about our own lives, including what we eat and wear, and our gender identities.

The understanding of privacy has expanded to protect intimate relationships, such as family and marriage, and to include autonomous decision making. Spatial privacy presumes access to private spaces, but this may not always be the case due to economic inability or social mores. Understanding privacy as choice allows greater protection to private acts of individuals, even if they are not protected by a spatial privacy. The right to privacy gives us a choice of preferences on various facets of life.

_______

_______

While the right to privacy is now well-established in international law, understandings of privacy have continued to differ significantly across cultures, societies, ethnic traditions and time. Even the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy has remarked on the lack of a universally agreed definition, despite the fact that “the concept of privacy is known in all human societies and cultures at all stages of development and throughout all of the known history of humankind”. Privacy is at the heart of the most basic understandings of human dignity, and the absence of an agreed definition does not prevent the development of broad understandings of privacy and its importance in a democratic society. As set out below, current conceptions of the right to privacy draw together four related aspects: decisional privacy, informational privacy, physical privacy and dispositional privacy.

-1. Decisional privacy: A comprehensive view of privacy looks to individuals’ ability to make autonomous life choices without outside interference or intimidation, including the social, political and technological conditions that make this ‘decisional privacy’ possible. This makes privacy a social value as well as a public good, and offers protection against outside intrusion into peoples’ homes, communications, opinions, beliefs and identities.

-2. Informational privacy: Privacy has more recently evolved to encapsulate a right to ‘informational privacy ‘, also known as data protection. The right to informational privacy is increasingly central to modern policy and legal processes, and in practice means that individuals should be able to control who possesses data about them and what decisions are made on the basis of that data.

-3. Physical privacy: A third and more straightforward conception of privacy is that of ‘physical privacy ‘, the right of an individual to a private space and to bodily integrity. Among other things, the right to physical privacy has underpinned jurisprudence supporting autonomy with respect to sexual and reproductive choices.

-4. Dispositional privacy is restriction on attempts to know an individual’s state of mind.

______

Dimensions of privacy:

People often think of privacy as some kind of right. Unfortunately, the concept of a ‘right’ is a problematical way to start, because a right seems to be some kind of absolute standard. What’s worse, it’s very easy to get confused between legal rights, on the one hand, and natural or moral rights, on the other. It turns out to be much more useful to think about privacy as one kind of thing (among many kinds of things) that people like to have lots of. Privacy is the interest that individuals have in sustaining ‘personal space’, free from interference by other people and organisations.

Drilling down to a deeper level, privacy turns out not to be a single interest, but rather has multiple dimensions:

- privacy of the person, sometimes referred to as ‘bodily privacy’ This is concerned with the integrity of the individual’s body. Issues include compulsory immunisation, blood transfusion without consent, compulsory provision of samples of body fluids and body tissue, and compulsory sterilisation;

- privacy of personal behaviour. This relates to all aspects of behaviour, but especially to sensitive matters, such as sexual preferences and habits, political activities and religious practices, both in private and in public places. It includes what is sometimes referred to as ‘media privacy’;

- privacy of personal communications. Individuals claim an interest in being able to communicate among themselves, using various media, without routine monitoring of their communications by other persons or organisations. This includes what is sometimes referred to as ‘interception privacy’; and

- privacy of personal data. Individuals claim that data about themselves should not be automatically available to other individuals and organisations, and that, even where data is possessed by another party, the individual must be able to exercise a substantial degree of control over that data and its use. This is sometimes referred to as ‘data privacy’ and ‘information privacy’.

With the close coupling that has occurred between computing and communications, particularly since the 1980s, the last two aspects have become closely linked. It is useful to use the term ‘information privacy’ to refer to the combination of communications privacy and data privacy.

During the period since about 2005, a further disturbing trend has emerged, which gives rise to a fifth dimension that wasn’t apparent earlier;

- privacy of personal experience. Individuals gather experience through buying books and newspapers and reading the text and images in them, buying or renting recorded video, conducting conversations with other individuals both in person and on the telephone, meeting people in small groups, and attending live and cinema events with larger numbers of people. Until very recently, all of these were ephemeral, none of them generated records, and hence each individual’s small-scale experiences, and their consolidated large-scale experience, were not visible to others. During the first decade of the 21st century, reading and viewing activities have migrated to screens, are performed under the control of corporations, and are recorded; most conversations have become ‘stored electronic communications’, each event is recorded and both ‘call records’ and content may be retained; many individuals’ locations are tracked, and correlations are performed to find out who is co-located with whom and how often; and events tickets are paid for using identified payment instruments. This massive consolidation of individuals’ personal experience is available for exploitation, and is exploited

With the patterns becoming more complex, a list may no longer be adequate, and a diagram below may help understand privacy dimensions:

________

________

Christopher Allen classifies Four Kinds of Privacy:

-1. The First Kind: Defensive Privacy

The first type of privacy is defensive privacy, which protects against transient financial loss resulting from information collection or theft. This is the territory of phishers, conmen, blackmailers, identity thieves, and organized crime. It could also be the purview of governments that seize assets from people or businesses. An important characteristic of defensive privacy is that any loss is ultimately transitory. A phisher might temporarily access a victim’s bank accounts, or an identity thief might cause problems by taking out new credit in the victim’s name, or a government might confiscate a victim’s assets. However, once a victim’s finances have been lost, and they’ve spent some time clearing the problem up, they can then get back on their feet. The losses also might be recoverable — or if not, at least insurable.

This type of privacy is nonetheless important because assaults against it are very common and the losses can still be very damaging. The Bureau of Justice report says that 16.6 million Americans were affected in 2012 by identity theft alone, resulting in $24.7 billion dollars being stolen, or about $1,500 per victim. Though most victims were able to clear up the problems in less than a day, 10% had to spend more than a month.

-2. The Second Kind: Human Rights Privacy

The second type of privacy is human rights privacy, which protects against existential threats resulting from information collection or theft. This is the territory of stalkers and other felonious criminals as well as authoritarian governments and other persons intent on doing damage to someone for personal for his or her beliefs or political views. An important characteristic of human rights privacy is that violations usually result in more long-lasting losses than was the case with defensive privacy. Most obviously, authoritarian governments and hard-line theocracies might imprison or kill victims while criminals might murder them. However, political groups could also ostracize or blacklist a victim.

Though governments are the biggest actors on the stage of human rights breaches, individuals can also attack this sort of privacy — with cyberbullies being among the prime culprits. Though a bully’s harassment could only involve words, the attackers frequently release personal information about the person they’re harassing, which can cause the bullying to snowball. For example Jessica Logan, Hope Sitwell, and Amanda Todd were bullied after their nude pictures were broadcast, while Tyler Clementi was bullied after a hall-mate streamed video of Clementi kissing another young man. Unfortunately, cyberbullying often results in suicide, showing the existential dangers of these privacy breaches.

-3. The Third Kind: Personal Privacy

The third type of privacy is personal privacy, which protects persons against observation and intrusion; it’s what Judge Thomas Cooley called “the right to be let alone”, as cited by future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in “The Right to Privacy”, which he wrote for the Harvard Law Review of December 15, 1890. Brandeis’ championing of this sort of privacy would result in a new, uniquely American right that has at times been attributed to the First Amendment (giving freedom of speech within one’s house), the Fourth Amendment (protecting one’s house from search & seizure by the government), and the Fifth Amendment (protecting one’s private house from public use). This right can also be found in state Constitutions, such as the Constitution of California, which promises “safety, happiness, and privacy”.

When personal privacy is breached we can lose our right to be ourselves. Without Brandeis’ protection, we could easily come under Panoptic observation where we could be forced to act unlike ourselves even in our personal lives. Unfortunately, this isn’t just a theory: a recent PEN America survey shows that 1 in 6 authors already self-censor due to NSA surveillance. Worse, it could be damaging: another report shows that unselfconscious time is restorative and that low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety can result from its lack.

Though Brandeis almost single-handedly created personal privacy, it didn’t come easily. The Supreme Court refused to protect it in a 1928 wire-tapping case called Olmstead v. United States; in response, Brandeis wrote a famous dissenting opinion that brought his ideas about privacy into the official record of the Court. Despite this initial loss, personal privacy gained advocates in the Supreme Court over the years, who often referred to Brandeis’ 1890 article. By the 1960s, Brandeis’ ideas were in the mainstream and in the 1967 Supreme Court case Katz v. United States, Olmstead was finally overturned. Though the Court’s opinion said that personal privacy was “left largely to the law of the individual States”, it had clearly become a proper expectation.

The ideas that Brandeis championed about personal privacy are shockingly modern. They focused on the Victorian equivalent of the paparazzi, as Brandeis made clear when he said: “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” He also carefully threaded the interface between public and private, saying, “The right to privacy does not prohibit any publication of matter which is of public or general interest.”

Today, personal privacy is the special concern of the more Libertarian-oriented founders of the Internet, such as Bit Torrent founder Bram Cohen, who demanded the basic human rights “to be free of intruders” and “to privacy”. Personal privacy is more of an issue than ever for celebrities and other public figures, but attacks upon it also touch the personal life of average citizens. It’s the focus of the “do not call” registry and other telemarketing laws and of ordinances outlawing soliciting and trespass. It’s the right at the heart of doing what we please in our own homes — whether it be eating dinner in peace, discussing controversial politics & religion with our close friends, or playing sexual games with our partners.

Though personal privacy has grown in power in America since the 1960s, it’s still under constant attack from the media, telemarketing interests, and the government. Meanwhile, it’s not an absolute across the globe: some cultures, such as those in China and parts of Europe, actively preach against it — advocating that community and sharing trump personal privacy.

-4. The Fourth Kind: Contextual Privacy

The fourth type of privacy is contextual privacy, which protects persons against unwanted intimacy. Failure to defend contextual privacy can result in the loss of relationships with others. No one presents the same persona in the office as they do when spending time with their kids or even when meeting with other parents. They speak different languages to each of these different “tribes”, and their connection to each tribe could be at risk if they misspoke by putting on the wrong persona or speaking the wrong language at the wrong time. Worse, the harm from this sort of privacy breach may also be increasing in the age of data mining, as bad actors can increasingly put together information from different contexts and twist them into a “complete” picture that simultaneously might be damning and completely false.

Though it’s easy to understand what can be lost with a breach of contextual privacy, the concept can still be confusing because contextual privacy overlaps with other sorts of privacy; it could involve the theft of information or an unwelcome intrusion, but the result is different. Where theft of information might make you feel disadvantaged (if a conman stole your financial information) or endangered (if the government discovered you were whistle blowing), and where an intrusion might make you feel annoyed (if a telemarketer called during dinner), a violation of contextual privacy instead makes you feel emotionally uncomfortable and exposed — or as boyd said, “vulnerable”.

You probably won’t find any case law about contextual privacy, because it’s a fairly new concept and because there’s less obvious harm. However social networks from Facebook and LinkedIn to Twitter and LiveJournal are all facing contextual privacy problems as they each try to become the home for all sorts of social interaction. This causes people — in particular women and members of the LGBT communities — to try and keep multiple profiles, only to find “real name” policies working against them.

Meanwhile, some social networks make things worse by creating artificial social pressures to reveal information, as occurs when someone tags you in a Facebook picture or in status update. To date, Google+ is one of the few networks to attempt a solution by creating “circles”, which can be used to precisely specify who in your social network should get each piece of information that you share. However, it’s unclear how many people use this feature. A related feature on Facebook called “Lists” is rarely used.

If a lack of personal privacy causes you to “not be yourself”, a loss of contextual privacy allows other to “not see you as yourself”. You risk being perceived as “other” when your actions are seen out of context.

_______

_______

Motivations for privacy breach:

Historically, the control of the communications and the flow of information, are mandatory for any entity that aims to gain certain control over the society. There are multiple entities with such interests: governments, companies, independent individuals, etc. Most of the research available on the topic claims that the main originators of the threats against privacy and anonymity are governmental institutions and big corporations. The motivations behind these threats are varied. Nevertheless, they can be classified under four categories: social, political, technological and economical. Despite the relation between them, the four categories have different backgrounds.

-1. Social & political motivations:

The core of human interaction is communication in any form. The Internet has deeply impacted in how social interaction is conducted these days. The popularity and facilities that the Internet offers, makes it a fundamental asset for the society. Currently, it is estimated that there are more than 4.8 billion users of the Internet in the world.

Any entity that gains any level of control over this massive exchange of information, implicitly obtains two main advantages: the capability to observe the social interaction without being noticed (hence, being able to act with certain prediction), and the possibility to influence it. Privacy and anonymity are the core values against these actions. Nevertheless, several authoritarian regimes implemented diverse mechanisms for the dismissal of both, privacy and anonymity.

Many of the authors highlight that the foundations of these threats are most often motivated for ideological reasons, thus, in countries in which freedom of speech or political freedom are limited, privacy and anonymity are considered an enemy of the state. In addition, national defense and social “morality” are also some of the main arguments utilized when justifying actions against privacy and anonymity.

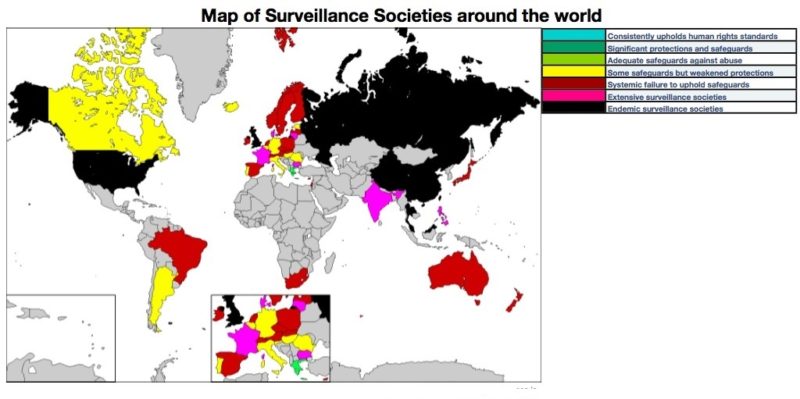

According to the OpenNet Initiative, there are at least 61 countries that have implemented some kind of mechanism that negatively affects privacy and anonymity. Examples of these countries are well-known worldwide: China, Iran, North Korea and Syria, among others. In addition, recent media revelations have shown that several mechanisms that are negatively affecting privacy and anonymity have been implemented in regions such as the U.S. and Europe.

-2. Technological issues:

There are some cases in which the threats against privacy and anonymity occur due to the lack of proper technology. Sometimes these threats can occur unintentionally. An example of this are bugs in software that are not discovered and somehow reveal information about the identity or data of the users. Also, misconfigured Internet services that do not use proper encryption and identity mechanisms when offering interaction with their users. Certain techniques utilized by the ISPs can lead to situations in which the user’s data and identity gets compromised even if the ISPs’ intentions are focused on bandwidth optimization. Finally, non-technological educated users can be a threat to themselves by unaware leaking their identity and data voluntarily but unaware of the repercussions (e.g. usage of social networks, forums, chats, etc).

-3. Economical motivations:

The impact and penetration of the Internet in modern society affects almost every aspect of it, with a primary use of it for commercial/industrial purposes. There are multiple economic interests that are related directly to the privacy and anonymity of the users. Several companies with Internet presence take advantage of user’s identity in order to build more successful products or to target a more receptive audience. Lately, the commercialization of user’s data has proven to be a profitable business for those entities that have the capability of collecting more information about user’s behavior. In addition, due to the popularity of Internet for banking purposes, the privacy and anonymity of the users are a common target for malicious attackers seeking to gain control over user’s economical assets.

______

______

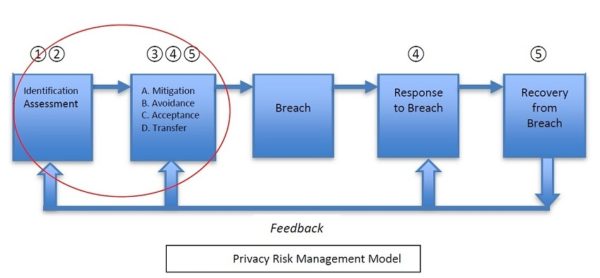

Privacy Risk Assessments: DPIAs and PIAs:

Once an organization has an initial understanding of its data collection, usage and sharing, the next step is to conduct Privacy Risk Assessments to understand the current and future privacy risks from those practices to the individual consumers and the organization. Organizations can engage in any number of individual or combined reviews in order to evaluate the implications of its business processes on privacy. There are many names for these Privacy Risk Assessments or Impact Assessment, but they are frequently referred to as either a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) or a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA).