Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

Hate

Hate:

_

Figure above shows Klansman (member of the Ku Klux Klan) raises his left arm during a “white power” chant at a Ku Klux Klan rally in the Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois, on December 16, 2000.

_____

Section-1

Prologue:

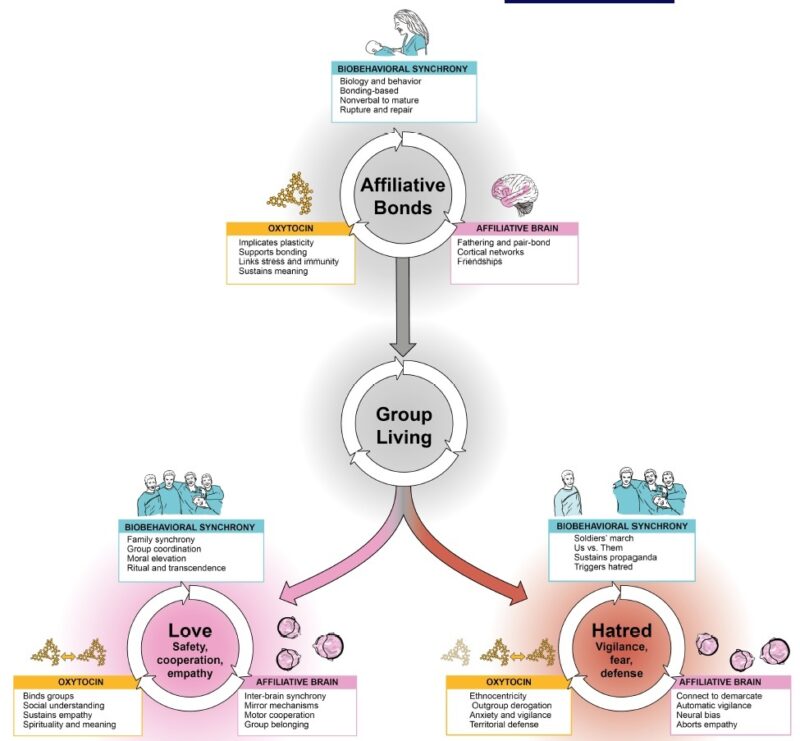

Human beings are biologically predisposed to divide humanity into ingroups and outgroups, and this comes with a great social cost – the capacity for hate. While we may view ourselves and our communities as benevolent and egalitarian, we often view outsiders as inhuman, unworthy, or alien, allowing us to victimize them in conscious and unconscious ways. Hate is among the most powerful of human emotions—it has caused great sorrow and suffering. All over the world, researchers are studying hate from disciplines like education, history, law, leadership, psychology, sociology and many others. After the genocide perpetrated by the Nazis in World War II, the expression “Never Again” became a familiar refrain. Yet, during the last half of the twentieth century and the first quarter of twenty-first century, society has witnessed staggering numbers of brutal and hateful acts. News sources are filled with reports of white supremacist groups murdering members of minority groups, religious zealots killing doctors who perform abortions, teenagers violently clashing with their classmates, genocide in Rwanda and Bosnia, and Israel Hamas war. These are not random or sudden bursts of irrationality, but rather, carefully planned and orchestrated acts of violence and killing. Underlying these events is a widespread and hazardous human emotion: hate.

_

Through the ages, music, art, and performance have grappled with how to portray hate, it’s devastating impact, and the relief of giving it up. We’re a society that loves to hate things. 67% of a survey respondents hate admitting their wrong, 5% of US workers admit they hate their job, and tragically, one person in every 1,000 in the US was a victim of a nonfatal hate crime in 2019. With the same word describing such a huge range of experiences, you might wonder what hate actually is. Hate is an intense aversion or hostility towards someone or something. It involves a strong negative emotional response and often includes a desire to harm, devalue, or exclude the target of hatred. According to Freud, “hate” is defined as an ego state that wishes to destroy the source of its unhappiness. Hate is an emotion that masks personal insecurities. Hatred is traumatizing physically, emotionally and morally. It therefore demands greater attention because the most common and lasting effects of hatred involve mental health concerns. Not only is it important to know the impact of hatred on the victim but perhaps more important is to understand the psychology of the person who hates (the hater). This may help in the prevention of various crimes like rape, murder and even genocide.

_

After the England men’s football team reached their first major final in 55 years, the national headlines should have been celebrating their exceptional achievement. Instead, the focus quickly turned to the vile racist abuse targeted at three Black players: Marcus Rashford, Bukayo Saka, and Jadon Sancho. These young men were subjected to widespread racist hatred and threats on social media platforms. The magnitude and ferocity of such incidents of hate is, regrettably, just the tip of the iceberg. “Whites don’t kill whites,” a witness quoted Gregory Bush as saying; he was arrested in the murders of two black shoppers at a Kentucky grocery store in 2018 and pleaded guilty to federal hate crimes. According to a recent study, there are at least 917 organized hate groups in the United States. Hate crimes start with hate speech, which often thrives in times of crisis. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Jonathan Mok, a college student from Singapore, reported being punched and kicked on the street in London. His attackers shouted, “We don’t want your coronavirus in our country.” Mok posted photos of his injured face on social media, writing, “Racism is not stupidity — racism is hate. Racists constantly find excuses to expound their hatred.”

_

Religion is contextual, and it can manifest itself in extremely damaging and violent ways. It can divide us from one another. It can create supremacist outlooks. It can create and be influenced by ethno-nationalist outlooks. But so many people find spiritual and political inspiration from their religions. As horrifying scenes of the Oct. 7 attack on Israel and the relentless bombing of the Gaza Strip that followed continue to dominate the news, incidents of antisemitism, Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism have surged in the world, leaving parents across the world struggling to calm their children’s fears and answer their questions — and to remind them that every person, everywhere, has the right to feel safe and respected. In an academic paper entitled The Palestinian–Israeli conflict: a disease for which root causes must be acknowledged and treated, authors noted that hatred goes side by side with violence. Hatred self-perpetuates, usually through cycles of hatred and counter-hatred, violence and counter-violence — sometimes manifested as revenge.

_

While the hate crime problem has moved up the political agendas of policymakers at every level of government in recent years, the phenomenon is hardly new. From the Romans’ persecution of Christians and the Nazis’ “final solution” for the Jews to the “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia and genocide in Rwanda, hate crimes have shaped and sometimes defined world history. In the United States, racial and religious biases largely have inspired most hate crimes. As Europeans began to colonize the New World in the 16th and 17th centuries, Native Americans increasingly became the targets of bias motivated intimidation and violence. During the past two centuries, some of the more typical examples of hate crimes in United States include the lynchings of African Americans, cross burnings to drive black families from predominantly white neighborhoods, assaults on homosexuals, and the painting of swastikas on Jewish synagogues.

_

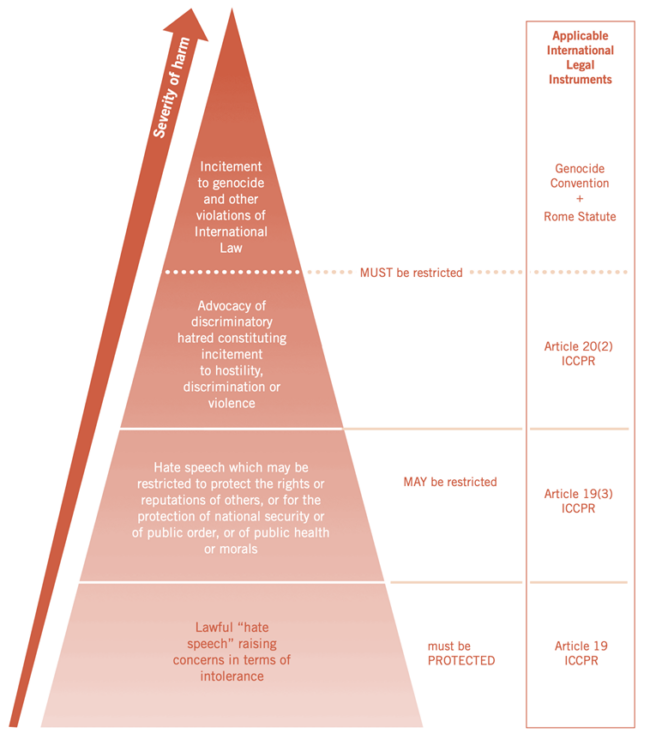

“Hate speech”, a shorthand phrase that conventional international law does not define, has a double ambiguity. Its vagueness and the lack of consensus around its meaning can be abused to enable infringements on a wide range of lawful expression. Many Governments use “hate speech”, similar to the way in which they use “fake news”, to attack political enemies, non-believers, dissenters and critics. However, the phrase’s weakness (“it’s just speech”) also seems to inhibit Governments and companies from addressing genuine harms, such as the kind resulting from speech that incites violence or discrimination against the vulnerable or the silencing of the marginalized. The situation gives rise to frustration in a public that often perceives rampant online abuse. Hate speech is spreading faster and further than ever before as a result of social media user growth and the rise of populism. Both online and offline, hate speech targets people and groups based on who they are. It has the potential to ignite and fuel violence, spawn violent extremist ideologies, including atrocity crimes and genocide. It discriminates and infringes on individual and collective human rights, and undermines social cohesion.

_

“In its published, posted, or pasted-up form, hate speech can become a world-defining activity, and those who promulgate it know very well—this is part of their intention—that the visible world they create is a much harder world for the targets of their hatred to live in,” says Jeremy Waldron in his book The Harm in Hate Speech. This statement summarises succinctly the deleterious impact of hate speech: a phenomenon that negatively alters reality to make it harder for the ones at the receiving end of such hate speech to live, as equals with dignity in the society. During the Rwandan Genocide which saw the killing of the ethnic minority Tutsis, one of the most used propaganda tools to spew hatred against the Tutsis was the Rwandan Radio which broadcasted inciteful anti-Tutsi propaganda. The radio station RTLM allied with leaders of the government incited Hutus against the Tutsi minority, repeatedly describing the latter as inyenzi, or “cockroaches,” and as inzoka, or “snakes.” Hutus, by reputation, are shorter than Tutsis; radio broadcasters also urged Hutus to “cut down the tall trees.” Within 100 days, an estimated 1 million people, the overwhelming majority of whom were Tutsis, lay dead. After all, what could be better used to convince a majority population to commit violent and gruesome acts against the minority ethnic groups than carefully crafted, provocative and inciteful words. Many wonder how is that possible? Tutsis are human beings. Researchers who study dehumanization know that not all people see it that way. It is very common for people around the world to look at entire groups of people — Muslims, Native populations, Romani people, Africans, or Mexican immigrants — as not fully human.

_

In America many years ago, they began to create laws, which were meant to protect the civil rights of African Americans. All these many years later there are still shootings, and riots and bigotry, and hatred all over the streets of America. Why is that? Well, it’s pretty obvious that laws can’t dictate the human psyche. We put the laws into effect, but people still hate. Only recently have laws begun to be put on the books about LGBT issues, so that while gays, lesbians and bisexuals can now marry in all 50 states, transgendered persons still can’t go into the appropriate bathrooms in some. And there are still very few laws that actually protect the LGBT person from getting fired for being LGBT. We have a long way to go here and the hate is still rampant. During a rally supporting then former President Trump, a 40-year-old male devotee was asked by a reporter who he hates. He quickly listed some famous Democrats whose behavior he found “disgusting.” When asked how far he was prepared to take his hatred, he recalled a story when he told his Democratic sister that if there was ever a civil war in the country, he would not hesitate to kill her. For many years, scientists have been trying to discover where in the brain something so terrible could originate.

_

Around the world, we are seeing an alarming rise of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim hatred. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream in liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes alike – and casting a shadow over our common humanity. It undermines social cohesion, erodes shared values, and can lay the foundation for violence, setting back the cause of peace, stability, sustainable development and human dignity. We’re having a master class on hate because we’ve no choice; it has moved from the part of our character we work hardest to suppress to the part we can least afford to ignore. Hate slipped its bonds and runs loose, through our politics, platforms, press and private encounters. And the further it travels, the stronger it grows. People unaccustomed to despising anyone, ever, find themselves so frightened or appalled by what they see across the divide that they are prepared to fight it hand to hand. Calls for civility are scorned as weak, a form of unilateral disarmament. It is us versus them, it is natives versus outsiders, it is whites versus blacks, it is Hindus versus Muslims and so on and so forth. So, I decided to study hate with the intention to reduce it.

_____

_____

Glossary:

Discrimination = The practice of unfairly treating different categories of people, especially on the grounds of ethnicity, national origin, gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation.

Bias = The disproportionate weight in favor of or against a person or an idea or thing, usually in a way that is inaccurate, closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair.

Prejudice = An adverse or hostile attitude toward a group or its individual members, generally without just grounds or before sufficient evidence.

Racial Slur = A derogatory, insulting, or disrespectful nickname for a person’s race.

Slander = An intentional false statement that harms a person’s reputation, or which decreases the respect or regard in which a person is held.

Gender = The social and cultural codes (linked to but not congruent with ideas about biological sex) used to distinguish between society’s conceptions of “femininity” and “masculinity.”

Hate = Hatred when used in a noun context.

______

______

Section-2

Introduction to hate:

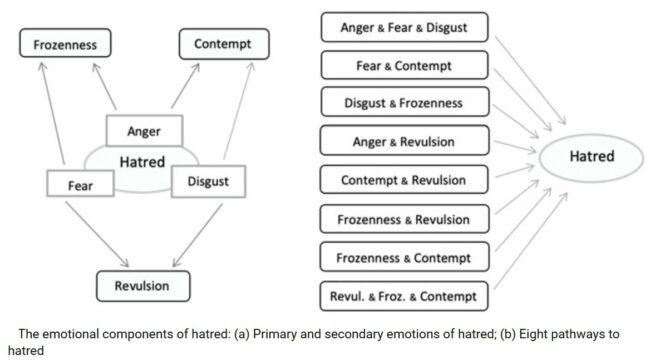

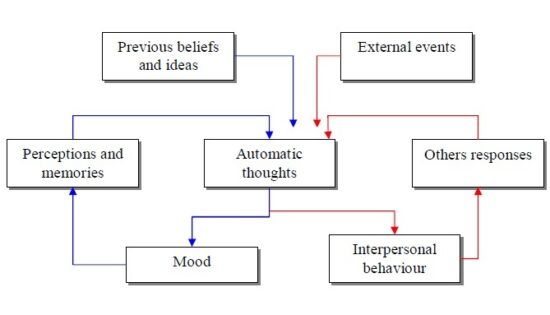

Commentary on the nature of hate may have begun with Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E), who believed that “hate rises without previous offense, is remorseless for the person experiencing it, incurable by time, and strives for the annihilation of its target.” Darwin, in 1872, described hate as a feeling that lacks a distinct facial expression and manifests itself as rage. Hatred has been studied for centuries by philosophers and theologians, and more recently by social psychologists, anthropologists and evolutionary scientists. There is no consensus on a definition of hatred that is scientific, comprehensive and holistic. Hatred is more than just an emotion. Eric Halpern, an Israeli psychologist and political scientist, defined hatred as “a negative emotion that motivates and may lead to negative behaviours with severe consequences.” Typically, hate is viewed as an extreme form of dislike, an amplified version of anger, disgust, or contempt and a readiness to do harm. Psychologists believe that hate is most likely to emerge in the presence of moral violations particularly when the targets of hatred are perceived as bad, immoral, and dangerous. Psychological studies have found that people feel more emotionally aroused, personally threatened, and inclined toward attack when experiencing hate as compared with disgust, contempt, anger, and dislike. People also report that hate feels more intense and durable than dislike, anger, and contempt. Hate between groups can also be intense but is typically based less on past one-on-one interactions, but rather on differences in beliefs such as one’s association with a political party. In studies that compared hate with other emotions, disgust shared the most commonalities with hate. Hate was not significantly different from disgust in terms of intensity and duration.

_

There is ample evidence in historical records, art, and artifacts that hate has very deep roots and that it stands tall, often pushing aside its counterparts, love and hope. As such, it is archetypal in nature, suggesting a biological and/or cultural origin that transcends history and geography. This idea is well articulated by the archetypal psychology of Carl Jung. The archetypal nature of hate can be understood in Jung’s conception of the shadow, the darker, repressed parts of the psyche that resist the pressures of self and society to conform and, when acted out, often assume violent forms of expression. There is so much hate in the world because hate is hard-wired in the brain. Like the role of killer, it is archetypal, motivating, and common to all human beings. And yet, according to researcher and primatologist Robert Sapolsky, the brain that hates others can be re-trained if human beings can imagine a role-reversal, where the hated ‘them’ and the righteous ‘us’ are experienced equivalently, in order to conceive of an integration of human existence. Sapolsky’s optimism, to many, may be contrary to reason and empirical evidence supported by grim statistics. And yet, if the killer is a role and if roles, when integrated with counter-roles, can be reconceived, maybe there is hope. It certainly appears hopeful to at least understand that biology is not necessarily destiny and that therapy of many kinds does have a salutary effect upon brain and behavior.

_

Everyday observations suggest that hate is so powerful that it does, not just temporarily but permanently, destroy relations between individuals or groups. An illustration comes from a story of a 20-year-old Kosovar Albanian woman who was asked to describe an experience of hatred in the context of a study by Jasini and Fischer (2018):

I was 10 years old when Serbian paramilitary men broke into my house with violence. They had guns in their hands and they approached my dad and my brothers and asked them all the money we had in the house. They threatened to kill them all if the family did not leave the house immediately. Few hours after this horror moment, my family and I left the village to seek refuge in the Albanian territory. Even now, ten years after the Kosovo war, I still hate the Serbians and can’t forget their hatred for us, nor their maltreatment of my family, relatives and neighbors [emphasis added]. I often talked about this event with my family members and friends, but never with Serbian people. Hate can thus remain long after an incident, and therefore can take a different form than a short-term emotional reaction to a specific event (like anger or disgust).

_

Hate begins with Bias:

Bias is the disproportionate weight in favor of or against a person or an idea or thing, usually in a way that is inaccurate, closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Hate generally starts with bias that is left unchecked. Bias is a preference either for or against an individual or group that affects someone’s ability to judge fairly. When that bias is left unchecked, it becomes normalized or accepted, and may even escalate into violence. The U.S. Department of Justice defines hate as “bias against people or groups with specific characteristics that are defined by the law.” These characteristics can include a person’s race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability and national origin. When the word “hate” is used in law, such as “hate crime law,” it does not mean rage, anger, or general dislike. In this context, “hate” means bias against people or groups with specific characteristics. Bias leads to discrimination. While bias can lead to discriminatory behavior, it does not always.

Bias leads to Prejudice:

Given the centrality of ‘prejudice’ to definitions of hate crime in the British criminal justice system, it is worth considering how prejudice has been understood in academic research and how it can help us to explain the phenomenon of hate crime.

A concise definition of prejudice has been provided by Abrams (2010):

‘Bias that devalues people because of their perceived membership of a social group’

However, most theoretical analyses of prejudice amplify that definition to emphasise its multi-faceted nature and its underlying antipathy. A recent example would be: ‘any attitude, emotion or behaviour towards members of a group which directly or indirectly implies some negativity or antipathy towards that group’ (Brown, 2010, p. 7)

But why do people hold prejudiced attitudes, emotions and behaviours? Social psychological theories offer several explanations for why perpetrators target people belonging to certain minority groups. These range from the purely psychological (for example, in terms of personality or cognitive processes), through accounts based on education and familial and group influences (for example, learning prejudiced attitudes at school, in the home or from peer groups), to ‘intergroup perspectives’ (that is, where prejudice is seen as the result of conflicts or tensions that exist between groups of people).

Hate is a form discrimination:

Discrimination is the practice of unfairly treating different categories of people, especially on the grounds of ethnicity, national origin, gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation. Hate is a harmful action against a person or property that is based on an unreasonable opinion about the other person’s identity. Hate often relates to race, colour, gender, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender expression, and other personal characteristics. Hate is a form of discrimination. Examples of hate as a form of discrimination include:

- threatening a co-worker because of their gender identity or gender expression

- making offensive comments during a job interview about a candidate’s Indigenous identity

- refusing to serve someone at a restaurant because of the person’s culture

- refusing to rent to a couple because of their sexual orientation

- displaying hateful comments about a person or community in a public place, including online

_

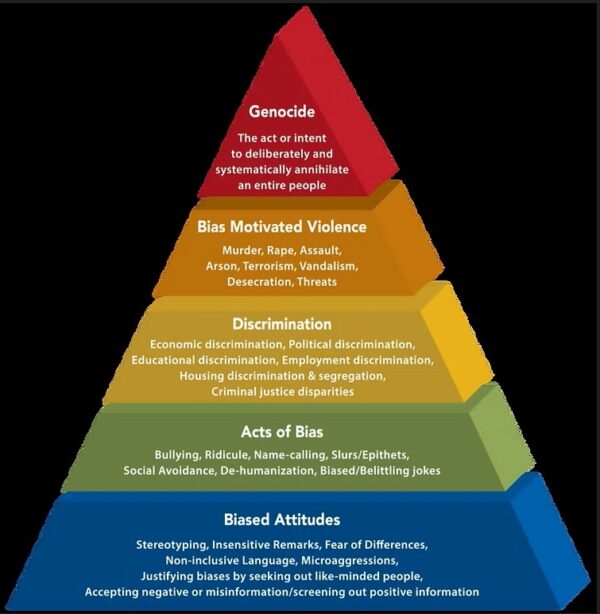

Pyramid of hate:

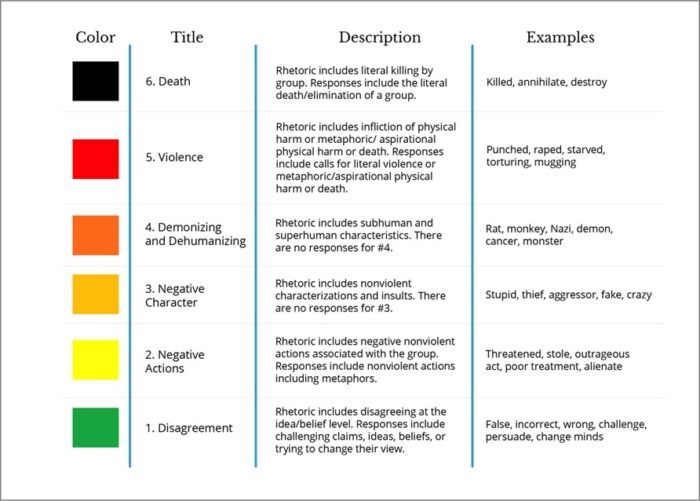

One way to think about hate is as a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid, hate is a feeling that grows from biased attitudes about others, like stereotypes that certain groups of people are animals, lazy or stupid. Sometimes these biased attitudes and feelings provide a foundation for people to act out their biases, such as through bullying, exclusion or insults. For example, many Asian people in the U.S. experienced an increase in hate incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. If communities accept biases as OK, some people may move up the pyramid and think it is also OK to discriminate, or believe that specific groups of people are not welcome in certain neighborhoods or jobs because of who they are. Near the top of the pyramid, some people commit violence or hate crimes because they believe their own way of being is better than others. They may threaten or physically harm others, or destroy property. At the very top of the pyramid is genocide, the intent to destroy a particular group – like what Jewish people experienced during World War II or what Rohingya people have experienced in Myanmar.

The pyramid of hate (below) shows how bias can escalate from attitudes to more severe forms of hate.

In the Pyramid, Biased Attitudes, such as stereotypes, misinformation and micro-aggressions, form the bedrock that enables escalation of hate and discrimination. Microaggressions are defined as the everyday, subtle, intentional — and oftentimes unintentional — interactions or behaviors that communicate some sort of bias toward historically marginalized groups. Pyramid shows a progression towards acts of bias, including dehumanisation and slurs, to Discrimination, Violence and, eventually, Genocide. Hate at the middle and higher levels of the pyramid happens because no one took action to discourage the biased feelings, attitudes and actions at the lower levels of the pyramid. The pyramid of hate shows how bias can escalate from attitudes to more severe forms of hate. Genocidal acts cannot occur without being upheld by the lower stages that act as a base for mass atrocities.

_

Hate in war:

The dehumanization of an enemy is a common tactic in warfare. Dehumanization reduces people to the status of animals or automata, and therefore not subject to the normal moral rules. It is a well-known method for persuading soldiers to kill indiscriminately when invading a country. By characterizing the enemy as not really human, worthy of hatred and contempt, leaders may try to justify their acts. Hate-based violence can lead to persistent cross-generational trauma, as research has shown. Yet it may be easier to encourage hateful actions than to prevent them. Chambers noted that avoiding hate in war was difficult: “Maintaining a level of empathy and compassion during conflict and war has to be an intentional action. It has to become an empowered response.”

_____

_____

The word hate:

According to James W. Underhill in his ethno-linguistic and cultural concepts, hate, just like love, is socially and culturally constructed. Hate, in the English language, invariably involves an object or a person, thereby implying a relationship with something or someone. But on a higher emotional plane, hatred is a form of animosity, frustration and hostility which churns within the subject and gives rise to an aimless desire for destruction. Hate describes a sense or feeling of deep hostility. It is a feeling that has many people in its grip, particularly in our current age. The word has also become standard in our descriptions of both communication and community. The terms “hate mail,” “hate speech,” “hate groups,” and “hate crimes” may be all too familiar, but they also contain an irony: the connection and bonding suggested by the words “speech” and “group” seem to work at crosscurrents with hate, which insists on maintaining separation between people.

_

Maybe we should explore the origins of this word! For starters, many people are likely to define hate as an emotion or feeling—or maybe a very negative attitude toward another person. But hate actually comes from the Old English word hata, which meant something like “enemy” or “opponent.” And like so many other English words, hate has made pretty big leaps and has come to take on a variety of meanings. Later in the Middle Ages the word would come to refer to intense anger, for example wrath, whether divine or human. In religious contexts, to hate something (sin, for example) meant to avoid, shun, or refrain from an action regarded as (spiritually) harmful. Nowadays we speak of “hating” a particular insect or cold pizza. There does not seem to be a deeply emotional hostility at work here. On the other hand, by hating individuals or whole groups of people—because of who they love, what they believe, or how they look—we go far beyond emotional hostility or even treating them as an adversary; we reject their very humanity.

_

Hate vs hatred:

Hate is the verb, hatred the noun. Hate is also used as a noun, but hatred is not a verb. From an intensity viewpoint, and when used in a noun context, there is no difference i.e. hate = hatred. The hate he felt for her matched the hatred she felt for him. You could switch the two words around in that sentence with no difference to the meaning. They’re both defined as meaning the same thing. In terms of how they feel… you could say hatred is a more intense version of hate. In terms of language, hate can also be used as a verb and a modifier (“I hate you”; “hate speech”), while hatred is only a noun.

_

Public display of hatred (PDH):

If I dislike you and can find your social media accounts, I can declare my dislike, using my real name or not. With just a few clicks, I can lacerate your looks, work, intellect, or politics. I can call you a lazy fascist slug. I might be wrong, of course, but I can call anyone anything at any moment. So can you. In a historical sense, this is new. For most of history, PDH required not just will but muscle, force, and risk. Our ancestors lacked the technology by which to proclaim instantly and effortlessly, for an audience of millions, “I just can’t stand this guy.” Public display of hatred (PDH) defines our times and has changed the way we interact. The very fact that PDH exists has transformed daily life into a battle zone. Hate is a hobby, a career, a mission, and a sport. It’s even creepier in that, for all its power to destroy, PDH manifests not face-to-face but at a distance, in virtual space. We have reached a point at which we love to loathe. We love it better when we loathe together. As a social species, we want millions to like our dislikes. The prevalence of PDH has changed our sense of being in the world. We feel constantly judged and watched as if through gunsights, subject to discussion, accusation, defamation, mockery, or bigotry. Certain public displays of hatred are sometimes legally proscribed in the context of pluralistic cultures that value tolerance.

_

Slow hate:

‘Slow hate’ is a term developed from Princeton Professor Rob Nixon’s idea of ‘slow violence’, often invisible, accumulative activities that degrade the natural environment and ‘slow hate’ does the same for the social environment. It involves minor violations of people and their culture that all add up; spiteful, discriminatory, denigrating or mean-spirited speech, for example, can be deeply problematic in its most extreme and explicit forms.

______

______

Delve deep in hate:

Hatred or hate is an intense negative emotional response towards certain people, things or ideas, usually related to opposition or revulsion toward something. Hatred is often associated with intense feelings of anger, contempt, and disgust. While hate relates to other negative emotions, it also has some unique features, such as the motivation to eliminate the object of your hate. Hatred is sometimes seen as the opposite of love. A number of different definitions and perspectives on hatred have been put forth. Philosophers have been concerned with understanding the essence and nature of hatred, while some religions view it positively and encourage hatred toward certain outgroups. Social and psychological theorists have understood hatred in a utilitarian sense. Hatred may encompass a wide range of gradations of emotion and have very different expressions depending on the cultural context and the situation that triggers the emotional or intellectual response. Based on the context in which hatred occurs, it may be viewed favorably, unfavorably, or neutrally by different societies.

_

Recently, neuroscience research has made the first steps toward mapping a hate circuit in the brain involving the putamen, the insula and the frontal cortex (Zeki & Romaya, 2008). But what is hate exactly? Most typically, hate is conceptualized as an extreme form of dislike, as well as an amplified version of specific emotions such as anger, disgust, or contempt (Allport, 1954; Aumer & Hatfield, 2007; Ben-Ze’ev, 2000; Darwin, 1872; Frijda, 1986; Staub, 2005). However, is hate indeed conceptually the same as dislike and these emotions? And if not, how is hate different from dislike and these emotions? Considerable theorizing has described what hate is, how it develops, how it relates to other discrete emotions, and what its cognitive, motivational, and behavioral characteristics are (e.g., Allport, 1954; Brewer, 1999; Fischer et al., 2018; Kucuk, 2016; Royzman et al., 2005; Staub, 2005; Sternberg & Sternberg, 2008). Nevertheless, research testing this theorizing empirically is remarkably scarce (Halperin et al., 2012; Royzman et al., 2005; Sternberg & Sternberg, 2008), and only a handful of studies have focused on the differences between hate and other emotional experiences such as anger, fear or dislike (Fischer et al., 2018; Halperin, 2008; Roseman & Steele, 2018; Van Bavel et al., 2018). Hate can develop both in interpersonal and intergroup relationships as a strong emotion. At the intergroup level, hate plays a role in for instance intergroup intractable conflicts (Halperin, 2008), political intolerance (Halperin et al., 2009), and war (Halperin et al., 2011). At the interpersonal level, hate has been characterized as the counterpart of love (Aumer et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2017), another strong and long lasting feeling with shared characteristics like its duration and intensity (Ben-Ze’ev, 2018), especially toward close targets (Aumer & Hatfield, 2007).

_

Unlike anger-emotions, hate is directed at a whole person rather than a specific action or event. It involves the belief that the other person is inherently bad or evil, and that there is little to no chance that this could change. This belief is usually not established from a single action, but a pattern of behavior. Furthermore, because you think this person is bad beyond change, you believe there is no point in any constructive approach. Rather, you just wish something bad would happen to them, or at least, that they would disappear from your life. Although hate can definitely lead to violent behavior, this is not necessarily the case, depending on the person and the situation. Often, someone will just avoid the hated person. If that is not possible, for example, because they work closely together, other strategies are used to create psychological distance. Hate can also be directed towards groups, a form that is often actively stimulated in wartime. Hating the enemy can relieve feelings of guilt for one’s own wrongdoings.

_

What we do know is that hate is intense and enduring, and it seems to be based on a view of its targets as essentially bad and threatening. For example, when the Hutus slaughtered the Tutsis in the Rwanda genocide of 1994, the hate they experienced appears to have been based on the perception that the Tutsis were essentially evil and that they should be eliminated. The hate embodied by the Ku Klux Klan and other extremist groups often goes back decades or longer, transcending generations and sometimes lying dormant until finding a new trigger. We also know that people can hate close individuals such as family members, friends or romantic partners. Whether one considers intimate violence between family members, the carnage of the World Wars or the wholesale slaughter of genocides around the world, the damage that humans can do to each other presents a serious threat to all of us. Theorists from Freud to the present have faced the challenge of developing an understanding of hate and violence.

_

The concept of hate can be operationalized as an instance of negative prejudice. As such, hate is a prejudice held by a person toward another individual, group, social object, category, or institution; it has distinct cognitive and emotional components. Hate is marked by intense emotional arousal and high meaningfulness, or conceptual salience, to the person. Hate is a simple word connoting extreme enmity and, as a construct, is readily understood, even by young children. Yet its prima facie obviousness is deceptive. Hate comes in various degrees and forms. Some hates are more powerfully felt and enduring than others. Some are socially shared, others are peculiar to an individual; some are one-way, others are mutual; some are enacted, others are not; and some are directed at individuals, others are directed at groups ranging from small family units to larger religious, ethnic, and political groups. Commenting on one of these dimensions of hate–severity–Kernberg described hate as occurring on a spectrum that includes mild, intermediate, and severe forms.

_

Hate is no stranger to humankind. Most (or maybe all) people are capable of experiencing the “intense hostility and aversion” toward some entity that is characteristic of this emotion. “True haters,” Gaylin observed, “live daily with their hatred. Their hatred is a way of life…. They are obsessed with their enemies, attached to them in a paranoid partnership.” In Gaylin’s view, the hatred they feel is a long-lasting enmity focused on some person or group that seeks the destruction of this target, more for the pleasure this will bring than for purposes of advantage, material gain, or revenge. But even more narrowly, the author focuses much of his attention on hate crimes, especially on the more extreme cases in which someone is deliberately killed because of his or her membership in a hated group. Hate crimes are typically differentiated from other types of crimes on the basis of the victim’s group membership; the offense probably would not have occurred if he or she had not belonged to that particular group.

_

Hate has personal, interpersonal, and societal dimensions. Unlike anger, hate resists efforts at emotion regulation; it typically takes life-changing events to reduce its effects. Where anger is about prevailing against perceived threats, hate is about destroying them. Once anger and resentment cross the line into hate, it’s extremely hard to come back from it, in part because it relieves self-doubt with an artificial sense of moral superiority. Hate endures because it justifies the harm done while hating.

When people feel unsafe within themselves, the expression of hate makes them feel empowered. It provides a sense of purpose in tearing down or destroying that which we hate. People without a sense of purpose are especially susceptible to hate.

Hate is heavily embedded with bias and distorted or oversimplified thinking. This makes it difficult on an interpersonal level to mitigate projection, to discern whether people we hate merely reflect qualities we don’t like about ourselves. Hate expressed on an interpersonal level is almost certain to evoke hateful responses from others. Expressing hate creates more hate.

On a societal level, hate holds groups together with a common enemy but tears them apart without one. Hate groups invariably develop factions and infighting, if not civil war.

Hate is embedded in presumed righteousness. Every hate group asserts its hate and aggression in the name of justice (human or divine). They feature indoctrination and forced reeducation, which, of course, increase hate.

__

Hate or hatred is an emotion of intense revulsion, distaste, enmity, or antipathy for a person, thing, or phenomenon; a desire to avoid, restrict, remove, or destroy its object. The emotion is often stigmatized; yet it serves an important purpose, as does love. Just as love signals attachment, hatred signals detachment. In psychology, Sigmund Freud defined hate as an ego state that wishes to destroy the source of its unhappiness. In a more contemporary definition, the Penguin Dictionary of Psychology defines hate as a “deep, enduring, intense emotion expressing animosity, anger, and hostility towards a person, group, or object.” Because hatred is believed to be long-lasting, many psychologists consider it to be more of an attitude or disposition than a (temporary) emotional state.

Hatred can be based on fear of its object, justified or unjustified, or past negative consequences of dealing with that object. Often “hate” is used casually to describe things one merely dislikes, such as a particular style of architecture, a certain climate, a movie, one’s job, or some particular food.

“Hate” or “hatred” is also used to describe feelings of prejudice, bigotry or condemnation against a person, or a group of people, such as racism, and intense religious or political prejudice. The term hate crime is used to designate crimes committed out of hatred in this sense.

Sometimes people, when harmed by a member of an ethnic or religious group, will come to hate that entire group. The opposite situation occurs too, where an entire group hates a single person. Some consider this to be socially unacceptable–Western culture, for example, frowns on collective punishment and insists that people be treated as individuals rather than members of groups. Others view such generalizing behavior as rational and indeed, necessary in order to ensure group survival in the face of competing groups or individuals who often have differing points of view.

Hate is often a precursor to violence. Before a war, a populace is sometimes trained via political propaganda to hate some nation or political regime. Hatred remains a major motive behind armed conflicts such as war. Hate is not necessarily logical and it can be counterproductive and self-perpetuating.

_

One of the characteristics of hatred is the need to devalue the victim more and more (Staub, 2005). At the end of the process, the object of the hatred loses all moral or human consideration in the eyes of the hater. When hatred intensifies, a certain fanatical obligation to get rid of the person or group that is the object of the hatred can easily arise (Opotow, 1990). Getting rid of that person sometimes means inflicting considerable damage or, taking it to an extreme, physical disappearance or murder: a frequent recourse in situations of intense hatred. In the end, it can produce a reversal of the moral code: killing the hated person or group is a right. The history of mankind is full of such examples: deportations of potential enemies by Stalin; ethnic cleansing in the Balkans war; the many cases of domestic violence ending in the murder of the partner.

There are two factors at the root of hatred: the devaluation of the victim and the ideology of the hater. Both of these factors mould and expand hatred. They reduce empathy, because the hater moves increasingly away from the object of their hatred. They remove obstacles that could limit our hatred towards others, by transforming our feelings into hatred. They not only change our ideas and feelings, but even the social norms that guide our behaviour towards the object of our hatred. The new behaviour ends up being accepted and normal; and institutions may even be created to promote and spread hatred. Palestinian children learn to hate Jews at school and Jewish radicals do the same with their children; Saharan children are taught to hate Moroccans; sometimes in the Basque Ikastolas, history is distorted to justify the existence of the Spanish invaders. We could continue with examples from everywhere.

_

Hate is conceptualized by multiple authors as an intense negative emotion, which is often compared with other negative emotions such as contempt, or anger, but has a much stronger response against the target such as complete avoidance or elimination of it. From a neurobiological perspective, multiple areas of the brain are involved in the experience of hate i.e., the parts of the limbic system, prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, etc. The experience of hate can take place at a self, interpersonal and intergroup level. Wherein, the latter has a much greater involvement of people with a far greater outreach surpassing the local boundaries due to the presence of the internet and other social media sites. Intergroup hate is often used by some people with a vested economic, social or political interest.

_

Hate Duration and Intensity:

In terms of duration, hate’s single episodes take more time to dissipate compared with other discrete emotions like anger (Verduyn & Lavrijsen, 2015), as it can remain dormant for decades (even across generations) waiting to be triggered (Sternberg, 2003). Lay people deem hate as an extreme, long-term, and highly emotional experience (Halperin, 2008) and report more long-lasting hate than short-term hate toward different out-groups (Halperin et al., 2012). In terms of intensity, it has been suggested that people experience hate with higher intensity than dislike (Goodvin et al., 2018). Previous attempts to categorize hate by intensity have proposed mild, moderate, and severe degrees of hate, with subcategories within each level (Sternberg & Sternberg, 2008), but without enough empirical evidence for such a taxonomy.

Hate Motivations:

Previous theorizing suggests that a key motivational goal underlying hate is to protect individuals from pertinent threats in the social environment. It has been assumed that hate emerges in the presence of a number of threats to the self, the in-group, or cultural values (Staub, 2005). For example, hate is associated with threats to life, freedom, resources, ideas, and the fulfilment of basic needs (Fromm, 1992; Staub, 2011), threats to selfesteem, self-interest, and personal goals (Baumeister & Butz, 2005; Beck, 2000), and threats to justice (Kucuk, 2016; Opotow & McClelland, 2007; Van Doorn, 2018). Also, hate is most likely to emerge in the presence of moral violations (Van Bavel et al., 2018) and when targets are perceived as essentially bad, immoral, and dangerous (Baumeister, 1997). However, few empirical studies have tested this association between threat and hate. At an interpersonal level, it has been speculated that hate serves isolated functions such as self-redress after interpersonal conflicts, motivating revenge, communicating emotional states, or reestablishing autonomy (Aumer & Bahn, 2016; Rempel & Sutherland, 2016). At the intergroup level, hate has been described as functional for political behaviors such as affiliation and in-group cohesion (Halperin et al., 2012).

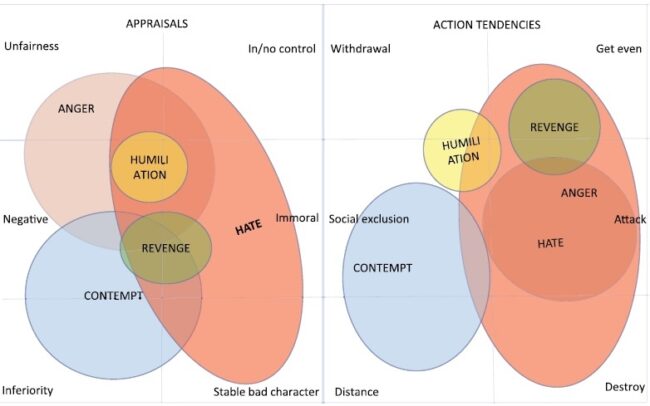

Hate Action Tendencies:

It has been typically argued that hate’s particular goal is harming or eliminating its targets (Allport, 1954; Baumeister & Butz, 2005; Fischer et al., 2018; Staub, 2005; Sternberg & Sternberg, 2008). Hate has been linked to attack action tendencies ranging from verbal aggression and hate speech to moral exclusion, physical aggression, and extreme violence (Chetty & Alathur, 2018; Opotow & McClelland, 2007; Sternberg, 2003). Alternatively, other studies have suggested instead that hate’s broader goal is to keep the targets out of one’s life, associating hate to avoidance-oriented action tendencies (Aumer & Bahn, 2016; Roseman & Steele, 2018). The distinctive action tendencies of anger, contempt, and disgust are less controversial. It is well-established that whereas anger prepares individuals for approach-oriented behaviors, disgust, and contempt promote avoidant-oriented behaviors (Hutcherson & Gross, 2011). Disgust aims at avoiding infectious agents, undesired sexual contact, and, more relevant for the present purposes, immoral actions and individuals (Tybur et al., 2009). On the other hand, contempt is associated with looking down, derogating, and excluding the targets (Schriber et al., 2017). Thus, whereas anger is primarily focused on changing a target’s unwanted behaviors, and contempt and disgust are focused on excluding and avoiding the targets, hate is focused on the target itself, and aims to physically, socially or symbolically eliminate it (Fischer et al., 2018). We expect, therefore, that as compared with dislike, anger, contempt, and disgust, hate will elicit more attack-oriented and less withdraw-oriented behaviors. However, there are many ways to cause hate-motivated harm in interpersonal relationships without necessarily engaging in physical violence (Rempel & Sutherland, 2016), and it is rather unlikely for a single individual to eliminate or harm an entire group. Thus hate’s attack-oriented behaviors do not necessarily always take extreme forms such as aggression or violence.

_

Desire to harm in hate:

Hate is an intense, negative emotional reaction to a target considered intrinsically malicious and unchangeable in its evilness (Fischer et al., 2018). The hated object is seen as dangerous, a threat to one’s values and identity, so the aim is its social, physical, mental, and symbolic destruction. A distinction can be made between interpersonal and intergroup hate, depending on whether the target is hated because of their membership to a particular group or their personal characteristics (Fischer et al., 2018).

There are many definitions and conceptions of hate. However, despite the conceptual discrepancies, there’s one component of hate that’s been accepted in all of them: the desire to harm. This desire can be a means to an end or an end in itself. Thus, an individual may yearn to harm another in order to restore an established order, elevate themselves, gain pleasure, assert their autonomy, or prevent abandonment. In all of these cases, regardless of the intent, the goal is to harm.

At the interpersonal level, it’s been claimed that hate fulfills different functions. For instance, self-repair, revenge, communicating an emotional state or restoring autonomy. At the intergroup level, it’s been considered a functional means for political behaviors, such as affiliation and cohesion within a group.

Hate, understood as a short or long-term feeling, is altered and intensified by other emotions, such as revenge, anger, and contempt. Different factors intervene in the complexity, chronicity, and stability of this feeling, especially motivational ones. Thus, hate is influenced by a motivation that intensifies the basic tendencies to action. Roseman (2008) has suggested that these action tendencies are an inherent part of emotional experience. He labeled them as ’emotional’ components of the emotional system.

_

Intolerance and hate:

The human race is an intolerable species. We are seldom welcoming of varying views, belief systems, and behaviors. We shun or outwardly reject those who differ from our own person. As a species, we are more apt to disregard or completely ignore anyone we disagree with. Such intolerance is no different than blatant acts of hate and discrimination. You may be asking yourself, how can ignoring or shunning be as reprehensible as violent acts. While the acts of shunning or ignoring lack the physical violence of the fist; shunning and ignoring are intentionally setting a precedent of intolerance and bigotry. It is this sort of behavior, attitudes, and percepts that is directly linked to instilling negative emotions (i.e. fear, distrust, hatred, worry, and personal distress). The prejudices of an individual can invoke rage, hostilities, and an overall spirit of negativity. While the intolerance begins within the mind and psyche of the individual, seldom does the intolerance keep isolated within the mind of the individual. Sadly, the venomous nature of intolerance is capable of creeping itself slowly into the minds of others who directly and indirectly interact with the ill mind. The spoils of intolerance are capable of diminishing and destroying every thread of communication. It is the egregious nature of intolerance that spurs on the prejudices and bigotry developed within the minds of those effected by such hate.

_

Hate & contempt:

Contempt and hate are both negative evaluations of a person. For example, a group of soldiers may feel both contempt and hate towards a fellow soldier who betrayed them and defected to the other side. The important difference is that hate is an evaluation that someone is evil or dangerous, whereas contempt judges someone to be inferior. In the example of the soldiers, the contempt is directed at the defected soldier’s lack of loyalty and patriotism, while the hate is directed at the fact that the soldier puts his comrades at danger. Someone can feel contempt for a very lazy person, but not hate him, because he poses no threat. Similarly, someone can feel hate for a tough competitor, as they pose a threat, but not feel contempt, because they are not seen as inferior.

Hate & Anger:

When you hate a person, you are likely to also be angry with them. However, the opposite is often not true. For example, a father can be angry with his children, but this does not mean that he hates them. An important difference is that anger evaluates someone’s action (you did something bad), whereas hate evaluates and entire person (you are bad). This also means that anger is usually temporary: if the person has apologized or if they have changed their behavior, there is no need to keep being angry. Hate, on the other hand, is more enduring. If you hate a person, you are convinced that they are beyond improvement, so it will likely last a long time, if not forever.

_

Hate is often misunderstood:

Hate involves an appraisal that a person or group is evil. While hate relates to other negative emotions, it also has some unique features, such as the motivation to eliminate the object of your hate. Revenge is often a part of hate, because the idea behind revenge is to want to hurt the person/group as much as you have been hurt by them. In daily life, the word hate is used very casually (e.g., I hate my teacher because she gave me a bad grade). People don’t usually mean that. When we ask participants to recall an experience when they felt hate, they do not usually recall these types of casual events. In fact, one of the challenges of studying hate is that most people can’t think of a time when they experienced true hate.

It seems easier to hate groups than individuals:

One surprising finding from research is that hate spreads and increases quicker if it’s directed at a group, rather than an individual. When you hate a group, the intensity of your hate can grow without you being confronted with specific persons or contrasting information from the group—you are basing your hate on stereotypes and prejudices. If you hate an individual, your hate may be countered with empathy or a reappraisal of the person when you encounter their positive side. In fact, when we asked people in conflict regions to tell us stories in which they hated someone, 80% talked about groups and not individuals.

______

______

Hate is a sentiment or emotion or extreme dislike:

Philosophers from the ancient time sought to describe hatred and today, there are different definitions available. Aristotle, for instance, viewed it as distinct from anger and rage, describing hate as a desire to annihilate an object and is incurable by time. David Hume also offered his own conceptualization, maintaining that hatred is an irreducible feeling that is not definable at all. There is strong disagreement about the nature of hate. Scholars of hatred have continually debated the question of whether hatred is an emotion, a motive (Rempel & Burris, 2005), or an (emotional) attitude or syndrome (Royzman et al., 2005). This debate is driven by the fact that one of hate’s core characteristics is that it generally lasts longer than the event that initially evoked it. The enduring nature of hatred is based in the appraisals that are targeted at the fundamental nature of the hated group. Given that hate is often not a reaction to a specific event, and not limited to a short period of time, the question is raised whether hate actually is an emotion, or rather an emotional attitude or sentiment (Allport, 1954; Aumer-Ryan & Hatfield, 2007; Frijda, 1986; Frijda, Mesquita, Sonnemans, & van Goozen, 1991; Halperin et al., 2012; Royzman et al., 2005; Shand, 1920, as cited in Royzman et al., 2005; Sternberg, 2005). In the last two decades, scholars (e.g., Fischer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016; Halperin, 2008; Sternberg, 2003) have resolved this contradiction between emotions and sentiments by suggesting that some “emotions” can occur in both configurations—immediate and chronic, and thus can be conceived of as a (short-term) emotion as well as a (long-term) sentiment.

Emotions are short-lived states that arise from a subjective experience, while sentiments are long-lasting states that are a person’s interpretation of their emotions.

_

Hate has been generally conceptualized as a negative emotional attitude (Allport et al., 1954; White, 1996) toward persons or groups who are considered to possess fundamentally negative traits (Allport et al., 1954; Ben-Ze’ev, 2000; Royzman et al., 2006; Sternberg, 2003). Similarly to other affective states (Frijda et al., 1991), hatred can be experienced both as an emotion (“acute hate”) and as a sentiment or emotional attitude (“chronic hate”) (Bartlett, 2005; Halperin et al., 2012).

The emotion hate (also referred to as “immediate hate”; Halperin et al., 2012) is much more urgent and occurs in response to significant events that are appraised as so dramatic that they lead to the kind of appraisals (e.g., “the ougroup is evil by nature”) and motivations (e.g., “I would like it to be destroyed”) that are usually associated with hatred. This intense feeling is often accompanied by unpleasant physical symptoms and a sense of fear and helplessness (Sternberg, 2003, 2005). It provokes a strong desire for revenge, a wish to inflict suffering, and, at times, desired annihilation of the outgroup. Studies by Halperin et al. (2012) unequivocally show that people are capable of short-term hate, following an unusual, mostly destructive, and violent event. In that very short period of time, they attribute the negative behavior of the outgroup to its innate evil character.

The two forms of hatred are related, yet distinct, and one fuels the occurrence and magnitude of the other. Frequent incidents of the emotion hate may make the development of the sentiment more probable (see also Rempel & Burris, 2005). At the same time, the lingering of hate as a sentiment constitutes fertile ground for the eruption of hate. Chronic haters, who encounter their targets or the consequences of their targets’ actions, most likely react with immediate hatred. These people evaluate almost any behavior of the hate target through the lens of their long-term perspective that the hate target is malevolent. As such, haters are probably more susceptible than others to systematic biases, such as the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977). What follows is that the mere presence, mentioning, or even internal recollection of the hated person or group can fuel hate as a sentiment. At the same time, the causal mechanism can work the other way as well. Repeated events of immediate hatred can very easily turn the hatred feeling into an enduring sentiment. Indeed, it is only natural that after repeated violent events of that kind, it becomes very difficult for people to forget earlier instances, and such feelings remain present for longer periods of time. In a way, hatred is an emotion that requires more time to evolve, but once it happens it takes much longer to dissolve, and it will always leave scars.

_

When hate is defined as an emotional attitude (versus hate as an emotion), it is a more stable disposition towards a hated object that relies significantly on cognition (Halperin et al., 2012). In this respect, hatred can be conceptually compared to dislike, which can be defined as a preference or negative disposition towards an object that influences our behavior (de Houwer & Hughes, 2020). Hatred and dislike have been historically conceptualized as two related concepts. For instance, German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously speculated that “Hatred is active, and envy passive dislike; there is but one step from envy to hate” (Edwards, 1908) and Darwin (1872) argued that “Dislike easily rises into hatred”, suggesting that the two belong on a common conceptual spectrum.

From a modern psychological perspective, what we label dislike and hatred both share some characteristics in terms of their dispositional nature and negative valence. However, the things that we say that we hate, as opposed to dislike, are transmissible, lead to false attributions, and motivate violent crimes (Sternberg, 2005). And these differences may be understood by taking into account the moral dimension of hate.

_

Is hate simply a stronger version of dislike? Or is it qualitatively different?

In a project, Cunningham, Dennis and Postdoctoral Researcher Jay J. Van Bavel conducted a scientific analysis of hate to identify its psychological underpinnings and motivational implications. The investigators studied the nature of hate through a series of seven studies using two methods: latent semantic analysis and social cognitive neuroscience.

Latent semantic analysis uses computers to take a body of text such as participant interviews and produce a vector space representation of how key words are related. The researchers used this method in a series of studies that included:

- Participants reporting three objects, people or concepts they hate, three they dislike, and detailed explanations why

- Participants reporting one object, person or concept they dislike, extremely dislike, and hate

- Analysis of real-world conflicts in which collective attitudes reflect hate.

Social cognitive analysis investigates the role of the human brain in producing thoughts and emotions. Here, the investigators did two studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG). In both experiments, participants were instructed to think about people and issues they dislike and those they hate so the investigators could see if different regions of the brain were involved.

Preliminary results show that hate is qualitatively different from dislike. While dislike was associated with avoidance, hate was associated with approach. Hate was also based on core moral or ideological beliefs, thus reducing positive attitudes or empathy toward others and possibly triggering violent motivations. By understanding the psychological nature of hate, the investigators hope that interventions can be introduced to reduce or eliminate it.

_

The Psychology of Hate: Moral Concerns Differentiate Hate from Dislike, a 2022 study:

Authors investigated whether any differences in the psychological conceptualization of hate and dislike were simply a matter of degree of negativity (i.e., hate falls on the end of the continuum of dislike) or also morality (i.e., hate is imbued with distinct moral components that distinguish it from dislike). In three lab studies in Canada and the US, participants reported disliked and hated attitude objects and rated each on dimensions including valence, attitude strength, morality, and emotional content. Quantitative and qualitative measures revealed that hated attitude objects were more negative than disliked attitude objects and associated with moral beliefs and emotions, even after adjusting for differences in negativity. In study four, authors analyzed the rhetoric on real hate sites and complaint forums and found that the language used on prominent hate websites contained more words related to morality, but not negativity, relative to complaint forums. The overall pattern of findings suggests that morality helps differentiate expressions of hate from expressions of dislike.

________

________

Hate and morality:

In general, moral values are strongly implicated in intergroup prejudice. Typically, this is a positive association, with the idea that morality—i.e. concerns about right and wrong—helps to combat prejudicial attitudes and actions. This is supported by research in psychology: works such as Rutland et al have proposed that morality plays a crucial role in children’s development of prejudice. Specifically, by way of an interaction with the emergence of group identity, children variably apply their “emerging beliefs about fairness, inclusion, and equality”. However, the positive influence of morality on prejudice—e.g. its reduction when applied during childhood development—is potentially at odds with the wider literature on morality and its potentially deleterious consequences. Specifically, moral motives may actually be a driver in acts of violence, rather than a pacifier. In the same vein, humans’ moral motives may drive them to out-group hatred and, consequently, hate-based behaviors including violence and forms of hate crime. Recent work has suggested such a connection, theorizing that moralized threats are a key instigator of acts of intergroup hate. There is now an emerging literature demonstrating that acts of hate and genocide are not committed due to lack of awareness, but because the perpetrators believe that “what they are doing is right”. Only recently have researchers begun to propose that violence and prejudice may have roots in moral intuitions. Can it be the case that the act of verbalizing hatred involves a moral component, and that hateful and moral language are inseparable constructs? A 2023 study ‘The (moral) language of hate’ attempt to find the answer. In this work, authors hypothesize that morality and hate are concomitant in language. In a series of studies, they find evidence in support of this hypothesis using language from a diverse array of contexts, including the use of hateful language in propaganda to inspire genocide, hateful slurs as they occur in large text corpora across a multitude of languages, and hate speech on social-media platforms. In post hoc analyses focusing on particular moral concerns, authors found that the type of moral content invoked through hate speech varied by context, with Purity language prominent in hateful propaganda and online hate speech and Loyalty language invoked in hateful slurs across languages.

______

______

Hate-Motivated Behavior:

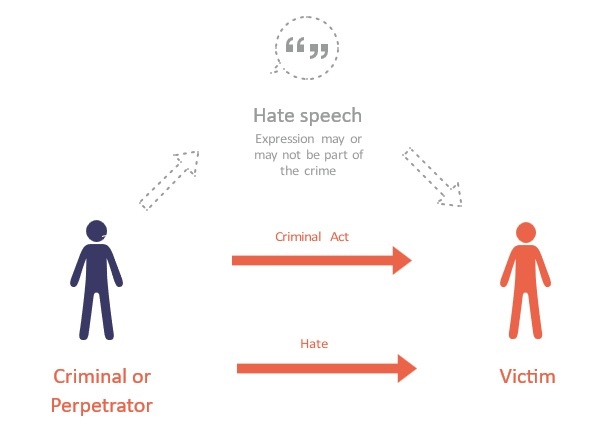

Hateful acts, especially hate crimes, are rooted in biases or even the simple preferences all people possess. For some people, these biases may manifest as prejudicial or stigmatizing beliefs. Prejudicial processes happen when people engage in cognitive shortcuts via stereotypes, which are exaggerated beliefs about a group or evaluations of an object, person, or group. Prejudicial beliefs also stem from negative emotional reactions to members of a targeted group. Prejudice ultimately shows up as discriminatory behaviors directed toward another person on the basis of group membership. Hate-motivated behavior, which is highly prevalent and likely underreported, comprises a continuum of behavior from subtle discrimination to violent crime. Targeted groups are heterogenous. Hate-motivated behavior can be thought of as verbal or nonverbal expressions of discrimination. For instance, hate speech comprises the verbal or written expression of prejudice aimed at harming another group. Hate crimes are commonly defined as harmful acts toward a person or group based on actual or perceived group membership. Acts of hate are thought to be effortful or intentional.

_

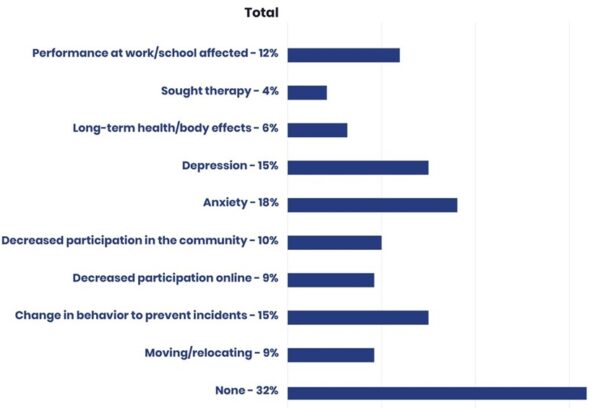

Hate-motivated behavior poses a threat to the population’s well-being, especially for vulnerable populations. Targeted communities are heterogenous—in its cataloging of hate crime statistics, the Federal Bureau of Investigation recognizes myriad groups targeted on the basis of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, religion, and disability. The negative health consequences for victims are numerous, with much of the literature focused on the victimization of people on the basis of race, sexual orientation, and gender minority status. Experiences of hate are associated with poor emotional well-being such as feelings of anger, shame, and fear. Moreover, victims tend to experience poor mental health, including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal behavior. Medically, impacts include poor overall physical health, physical injury, stress, and difficulty accessing medical care. Victimization is also associated with poor health behaviors such as alcohol or drug use and unhealthy coping strategies such as emotion suppression. The experience of hate-motivated behavior can result in blaming of and lower empathy toward fellow victims.

_

Research demonstrates that perpetrators of hate crimes tend to be of younger age, male sex, and White race. Personality traits such as high emotional instability have been shown to be background risk factors for discrimination. Potential drivers of hate-motivated behavior include a range of attitudes (for example, high social dominance orientation) and prejudices, mental shortcuts (for example, dichotomous thinking), and disinhibiting behaviors (for example, alcohol use). The same prejudices and attitudes (for example, social dominance orientation) that drive hate are also empirically linked to support of far-right political figures and movements, such as President Donald Trump, Brexit, and the UK Independence Party. Interpersonal risk factor research highlights the impact of both negative family and peer group influences on subtle discrimination and far-right extremist behavior, respectively. A variety of perceptions of outgroup members (for example, as a threat) may also precipitate hateful acts. Lack of exposure to diversity may also be associated with sexist behavior.

______

______

Do animals feel hate?

No, animals don’t really hate, that emotion is solely for humans.

People disagree about the nature of emotions in nonhuman animal beings (hereafter animals), especially concerning the question of whether any animals other than humans can feel emotions (Ekman 1998). Pythagoreans long ago believed that animals experience the same range of emotions as humans (Coates 1998), and current research provides compelling evidence that at least some animals likely feel a full range of emotions, including fear, joy, happiness, shame, embarrassment, resentment, jealousy, rage, anger, love, pleasure, compassion, respect, relief, disgust, sadness, despair, and grief (Skutch 1996, Poole 1996, 1998, Panksepp 1998, Archer 1999, Cabanac 1999, Bekoff 2000). The tendency to feel hate can be useful in a survivalistic sense but animals are incapable of feeling hate. They can have aggression towards another animal or person but that does not mean they “hate” them. Animals can be wary and they certainly can feel fear, anger and love. Wild creatures will explode with rage and anger, but they will not hate. That takes a capacity for abstraction and judgement they don’t have. While dogs can experience a range of emotions, including fear, anxiety, and affection, the concept of hate is typically beyond their cognitive capacity. Negative behaviors exhibited by dogs are often rooted in instinct, learned responses, or underlying stressors.

_______

_______

What breeds hate?

Hate is a negative feeling of hostility and aversion towards certain people, things, and ideas. Hate is often associated with feelings of fear, anger and discomfort. It often induces harmful behaviour and rift among the people and increases violence, discrimination, and oppression. The hate is change with the individual perspective and hence can be manifested in various forms. It can be racial hatred (hate based on the person’s race or creed), religious hatred (prejudice against individuals or groups based on their religious beliefs), homophobia (hate on the basis of sexual orientation mainly people with LGBTQIA+), sexism (prejudice against someone based on their gender), political hatred (hate because of political belief) and class hatred (prejudice of economic background). Hate can be induced by several factors, which include individual, societal and psychological elements. It can stem from a variety of sources, such as cultural, social, political, and personal factors. The reasons for hatred can be complex and multifaceted, making it a challenging topic to tackle.

_

Fear:

The common denominator in most acts of hatred is fear, usually fear of different types of people or ideas. This is why hatred is most often directed toward people of differing race, sexual orientation, religious background or some other criterion. People are threatened by the unknown and seek to extinguish this fear, resulting historically in massive death tolls, slavery and other injustices. Merriam-Webster defines xenophobia as “fear and hatred of strangers or foreigners or of anything that is strange and foreign.” Some psychologists assert that hatred isn’t inherent at birth. Instead, they believe this emotion is learned over time, sometimes rearing its ugly head later in life in the form of bigotry, prejudice and even hate crimes.

Long before the existence of codified law, uncivilized people lived defensively and territorially. These people didn’t take kindly to unfamiliar people on their turf. Rather than approaching with a handshake and a smile, they usually responded to possible threats with violence. Since the people who took the “kill rather than be killed” approach survived and reproduced, this attitude evolved over time into the instant classification of strangers. As such, the idea of “us vs. them” became instinctual and socially acceptable.

Hatred is the natural reaction to fear. Fear of rejection, abandonment, suffocation, and mortality can all lead to hate. When a group threatens our beliefs, we may fear and then hate them. Everyone fears pain, injury, and death. If we did not have hatred, we would have no incentive to overcome the source of the fear and subdue or eliminate it, and therefore we would succumb to it and allow ourselves to die.

_

From the neurological point of view, fear and aggression are motivated by an automatic response to perceived threats, the well-known fight, flight, or freeze phenomenon that is wired into our limbic system. This familiar trifecta of stress responses is rooted in the desire to stay alive—as well as to live well and to avoid injury of all kinds, including to our self-esteem, self-identity, and emotional well-being. This fear-driven motivational system designed to protect us involves the amygdalae, a pair of small structures deep in the brain, which are the center for primitive emotions, including fear. And here’s the thing: two-thirds of the cells in the amygdalae are designed to respond to unpleasant experiences. The amygdalae react far more rapidly and completely to negative than to positive stimuli. To put it another way, the “stick” sticks in your mind while the “carrot” makes much less of an impression. This leaves you predisposed to make negative interpretations and jump to fear-based conclusions. It’s not hard to see how we might have ended up with this negatively biased hardwiring. In evolutionary terms, natural selection favors the negativity bias. Mistaking a benign situation for a threatening one may be hard on your nervous system, but it is not as immediately dangerous as the opposite mistake—not recognizing a threat. Our brains are designed to look at the worst-case scenario in order to survive. We need to recognize threats in our environment, whether we’re avoiding a tripping hazard or a cheating ex. Our bias toward negativity helps us determine who to cooperate with and who to compete with.

_

Hatred is a forced, adaptive response to unrelenting fear. No one arrives in this world with the ability or will to hate others. It is a learned internal response in reaction to inescapable, or repeated painful experiences inflicted by others. Hate can be a necessary ‘psychological defense’ when a child (or adult) is — 1) fully dependent/subjugated by another and is, 2) unable to control, predict, mitigate, or escape the terror or suffering. Experiences that breed hatred include:

-chronic physical or emotional abuse of a child by a parent or other trusted adult

-victimization that occurs in ‘forced’ environments (school, jail, camp, slavery)

-chronic abuse from those with ‘absolute’ authority (police, doctors, parents, teachers, priests)

-abuse or torment among unequal siblings, neighbors, teammates, classmates, etc. in which access is inevitable.

Within groups or populations, hatred is sown during the terrors of war, genocide, oppressive dictatorships, etc.

Second-hand hate can be bred indirectly as it is ‘taught’ through indoctrination, training, harsh example, fear manipulation, etc. Tribal war-cultures, extremist military groups, terrorist organizations, and extreme cults may be examples here.

_

There are other key factors, which can easily influence hate:

- Personal Experience: People who have experienced negative attitudes from a certain group of people are likely to develop a negative feeling towards them. For example, if a person gets bullied by an individual of a specific race may develop a racist attitude towards the whole race.

- Fear and insecurity: Hate is often influenced by the fear of losing something, it can be identity or privileges.

- Socialization: People can learn about hate from their family, peers, and communities. If an individual is exposed to negative messages about a certain group. They are most likely to adopt a negative attitude towards that group which influences hate.

- Media: Media plays an important role in influencing hate. If a news channel is broadcasting stereotypical negative news about a certain group, then, the people who are watching are most likely to develop a negative attitude towards that group and this ultimately influences the hatred and prejudice.

- Economic Factor: Economic inequality can contribute to, and influence prejudice and hatred. People who feel economically threatened often scapegoat minority people.

- Political Factor: Political agendas and propaganda can manipulate the people and induce hatred and prejudice among their followers.

- Psychological factor: An individual can include the personality trait an individual owns by birth. Some people have hatred in their basic trait due to low levels of empathy and high levels of aggression.

__

The psychology of hate involves the following aspects:

-Hate is an appraisal that a person or group is evil.

-It includes a strong negative emotional response and often a desire to harm, devalue, or exclude the target.

-Hate is a secondary emotion learned from personal experiences, social conditioning, and cognitive processes.

-It often stems from mistrust, feelings of powerlessness, or vulnerability.

-Experiences of hate are associated with poor emotional well-being and mental health issues.

_

Hate can cause a number of consequences which can be devastating for both individuals and society:

- Physical and emotional harm: Hate influences an individual to commit a crime which harms the beings physically and causes emotional disbalance. Victims of hate crime are most likely to experience stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Post-traumatic stress disorder).

- Social isolation and exclusion: People do not like to be with a person who is full of negativity so, the person who shows the feeling of hating is most likely to experience social isolation and exclusion from peers and society. This results in them having mental distress and disturbance in well-being.

- Reduced opportunities: Job opportunities can be reduced as hate can lead to people being discriminated against in employment and areas of job, which can affect your potential to achieve higher goals.

- Increased violence and crime: In extreme cases, hatred can increase the rate of violence and crime among the people who are influenced by the negative attitude which can result in acts of genocide, physical harm, and loss of lives.

- Social unrest and division: Hatred can create social unrest and division among a group of people. It also creates distrust among the group of people and makes it difficult to build a cohesive and just society.

These consequences can be harmful to the individual and the whole society, so one should combat these consequences by making some changes in your behaviour and actions.

_

Synopsis of hate:

- Hate is an intense aversion or hostility towards someone or something rooted in personal experiences, social conditioning, and cognitive processes.

- Reasons for developing strong feelings of dislike or hatred include misunderstanding, negative experiences, societal influence, fear of the unfamiliar, and personal insecurities or biases.

- Hate is influenced by social and cultural factors, such as upbringing, cultural background, and the desire for belonging. It often stems from an “us vs. them” mentality, leading to discrimination, violence, and division.

- Psychologically, hate can be fueled by negative personal experiences, the need for a scapegoat, insecurity, and unconscious reactions to non-verbal cues.