Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

MONEY

Money:

_

____

Section-1

Prologue:

Somebody once asked the late bank robber named Willie Sutton why he robbed banks. He answered: “That’s where the money is.” Money is something we encounter in every facet of our daily lives. The first thing that springs to mind for most of us when we hear the word “money” is coins and banknotes. We talk about “making money” when we refer to our income. We say that we are “spending money” when we go shopping. For major purchases we sometimes have to “borrow money” by taking out a loan, either from someone we know or from a bank. It is no accident that the term “money” gets used in so many different ways: it is a reflection of the myriad functions that money performs in our economic lives.

_

Money is one of the fundamental inventions of mankind. Economists say that the invention of money belongs in the same category as the great inventions of ancient times, such as the wheel and the inclined plane. The creation of money is made possible because human beings have the capacity to accord value to symbols. Money is a symbol that represents the value of goods and services. The acceptance of any object as money – be it wampum, a gold coin, a paper currency note or a digital bank account balance – involves the consent of both the individual user and the community. Thus, all money has a psychological and a social as well as an economic dimension. As human consciousness has evolved, the nature and function of money has evolved too. While a history of money may trace the origin and usage of different forms of money at different times and in different parts of the world, an evolutionary perspective on money traces the social and psychological changes in human attitude and collective behavior that made possible this historical development.

_

Money is the commonly accepted medium of exchange. In an economy which consists of only one individual there cannot be any exchange of commodities and hence there is no role for money. Even if there are more than one individual but they do not take part in market transactions, such as a family living on an isolated island, money has no function for them. However, as soon as there are more than one economic agent who engage themselves in transactions through the market, money becomes an important instrument for facilitating these exchanges. Economic exchanges without the mediation of money are referred to as barter exchanges. Humans passed through a stage when money was not in use and goods were exchanged directly for one another. However, they presume the rather improbable double coincidence of wants. Consider, for example, an individual who has a surplus of rice which she wishes to exchange for clothing. If she is not lucky enough she may not be able to find another person who has the diametrically opposite demand for rice with a surplus of clothing to offer in exchange. The search costs may become prohibitive as the number of individuals increases. Thus, to smoothen the transaction, an intermediate good is necessary which is acceptable to both parties. Such a good is called money. The individuals can then sell their produces for money and use this money to purchase the commodities they need. Though facilitation of exchanges is considered to be the principal role of money, it serves other purposes as well like store & measure of value.

_

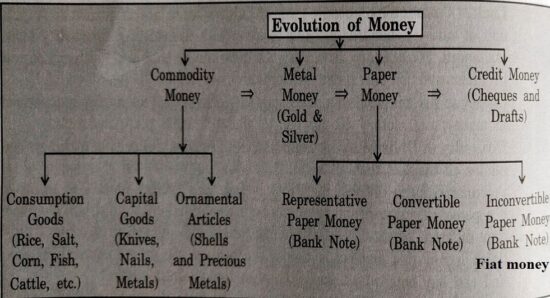

Money has undergone a long process of historical evolution. The inconveniences and drawbacks of barter led to the gradual use of a medium of exchange. If we study history of money, we shall find that all sorts of commodities like seashells, pearls, precious stones, tea, tobacco, cow, leather, cloth, salt, wine, etc. have been used as a medium of exchange. It is called commodity money. Inadequacy of commodity money led to the evolution of metallic money (gold and silver). The problem of uniformity of weight and purity of precious metals led to private and public coinage. This process was finally taken over by the state as one of its essential features and ultimately commodity money gave way to paper money which means currency notes. The process of evolution of some better medium of exchange still continues. As the volume of transactions increased, even paper money started becoming inconvenient because of time involved in its counting and space required for its safe keeping. This led to introduction of bank money (or credit money) in the form of cheques, drafts, bills of exchange, credit cards, etc. We use coins and banknotes but the balances we hold in our bank accounts are now recorded only in the form of bits and bytes. Although we cannot even hold it in our hands, we still accept it as money because we trust in its value. Ultimately, money is whatever is generally accepted as money within a society at a given time. Money is what money does. Money is so important that when no official money exists, people often create it. For example, during World War II, prisoners in prisoner-of-war camps used cigarettes as money. All other goods were priced in terms of cigarettes, and prisoners willingly accepted them as payment for any other good. While cigarettes have value to smokers, once they become money, they gain value in terms of everything they can be exchanged for, whether a person smokes or not. People will always find something to serve as money, even with no government to enforce its legitimacy.

_

Money for the sake of money is not an end in itself. You cannot eat dollar bills or wear your bank account. Ultimately, money is only useful because you can exchange it for goods and services. As the American writer and humourist Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914) wrote in 1911, money is a “blessing that is of no advantage to us excepting when we part with it.” Businesses and government use money in similar ways. Both require money to finance their operations. By controlling the amount of money in circulation, the federal government can promote economic growth and stability. For this reason, money has been called the lubricant of the machinery that drives our economic system. Money is indispensable in an economy, whether it is capitalistic or socialistic. Our banking system was developed to ease the handling of money. Money is a necessary component of any democracy: it enables political participation, campaigning and representation. However, if not effectively regulated, it can undermine the integrity of political processes & institutions and jeopardize the quality of democracy. Thus, regulations related to the funding of political parties and election campaigns, commonly known as political finance are a critical way to promote integrity, transparency and accountability in any democracy. In order to appreciate the conveniences that money brings to our lives, think about life without it.

_

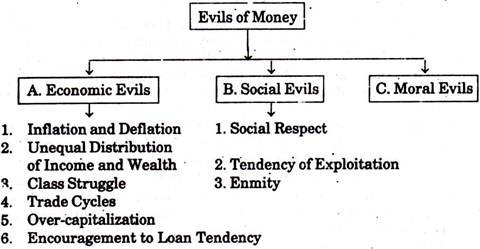

Money was a clever and convenient invention; it was designed as a means of exchange and a measure of wealth. But somehow that has changed; what was once solely a means to an end has become the end itself, and what was a measure of wealth has become wealth itself. Take for example agriculture, the purpose of which was to produce nutritious food whilst ensuring that the land remained in good heart for all future generations and for the good health of biotic communities. Agriculture was a way of life that gave farmers their dignity, and in turn they cultivated the crops with tender loving care and considered their work intrinsically good. Then came money, which changed everything: agriculture turned into agribusiness and the paramount purpose of it became the making of money. Food became a commodity and yet another means of making large profits. We can cut down the rainforest to make money, we can pollute the rivers and over-fish the oceans for profit, we can destroy the local economy in search of cheaper goods, no matter how much CO2 is emitted in the process. Nothing is forbidden, just as long as it adds to GDP and increases the share value of corporations and companies. Ethics, morals and human dignity are all secondary and subservient to the profit margin. All money tends to corrupt, and absolute money corrupts absolutely. This is an ancient message. You can find it in the Bible (“the love of money is the root of all evil”) and in the writings of ancient Greek philosophers and Renaissance moralists. You can’t buy a friend because if you know you’ve paid someone to be nice to you it ceases to be a “real” friendship. Nonetheless rich people tend to have more “friends” than poor ones. Money creates conflicts within family and between families. Money is the root cause of many crimes. Von Mises remarked: “Money is regarded as the cause of theft and murder, of deception and betrayal.” I have seen people trying to bribe God with money so that their sins can be pardoned. I have also seen people who believe that money is God no matter means to obtain it.

_____

_____

Quotes on money:

-1. The money which a man possesses is the instrument of freedom.; that which we eagerly pursue is the instrument of slavery.

~ Jean-Jacques Rousseau

-2. Top 15 Things Money Can’t Buy

Time. Happiness. Inner Peace. Integrity. Love. Character. Manners. Health. Respect. Morals. Trust. Patience. Class. Common sense. Dignity.

― Roy T. Bennett, The Light in the Heart

-3. If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people he gave it to.

― Dorothy Parker

-4. Libraries will get you through times of no money better than money will get you through times of no libraries.

― Anne Herbert

-5. The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax.

― Albert Einstein

-6. Money may not buy happiness, but I’d rather cry in a Jaguar than on a bus.

― Françoise Sagan

-7. I’ve been rich, and I’ve been poor; believe me, rich is better.

―Mae West

_____

_____

Abbreviations and synonyms:

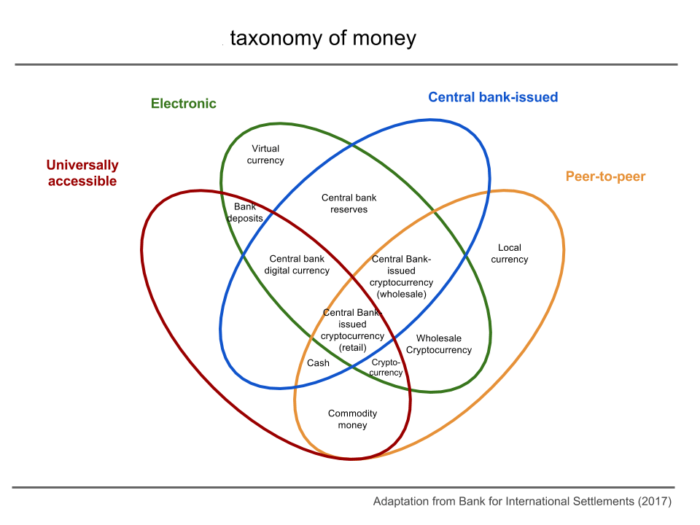

CDBC = central bank digital currencies

M0 = base money

MZM = money zero maturity

TVM = time value of money

UCC = Uniform Commercial Code

EFTS = electronic funds transfer system

FRB = Federal Reserve Board

Fed = Federal Reserve

OMO = open market operations

MMT = Modern Monetary Theory

MMMF = Money Market Mutual Funds

PPP = Purchasing Price Parity

CPI = Consumer Price Index

CRR = cash reserve ratio

IOU = I owe you

______

Some facts about money:

-The U.S. currency paper is composed of 25% linen and 75% cotton. About 4,000 double folds (first forward and then backwards) are required before a note will tear.

-The copper coin production in the Chinese Song Dynasty reached the highest output, once within a period, 10000 tons of copper a year were used, if line up the coins one by one, it is 128333 kilometers, about 3 circles round the earth, this was only one year’s output, no one knows where so much copper were collected.

-Records shows China had ways to avoid counterfeited paper money nearly 1000 years ago, and laws for that were also published then, even printed on the paper money.

-The United States Secret Service was originated in 1865 to combat counterfeit money. At the time, as much as one third of all the money in the United States was estimated to be counterfeit. Currently, about $250,000 in counterfeit money appears each day.

-As of mid-July 2017, there was more than $1.56 trillion in U.S. currency in circulation, with $40 billion in coins.

_______

Terminology:

|

Key term |

Definition |

|

money |

any asset that can serve the three functions of money; 1) medium of exchange, 2) a store of value, and 3) a unit of account. |

|

a medium of exchange |

the ability for something be used to purchase something else, such as “I can use this 5 dollar bill to buy a grilled cheese and peanut butter sandwich” |

|

a store of value |

the ability to delay using money as a medium of exchange until later, such as “I am going to keep this $5 bill in my wallet so I can buy a grilled cheese and peanut butter sandwich tomorrow” |

|

a unit of account |

the ability to represent the value of an item, such as “this grilled cheese and peanut butter sandwich costs $ 5” |

|

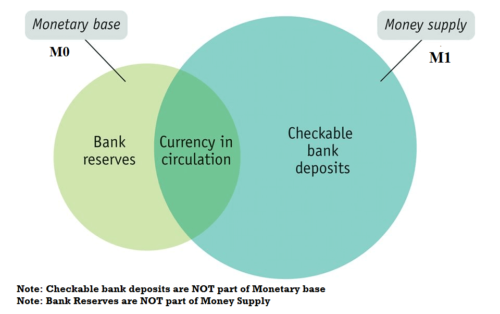

currency in circulation |

money outside of banks, such as money in your wallet or your cupboard; the money in your pocket is currency in circulation, but the money in your bank account is outside of circulation. |

|

currency in vaults |

(Also called reserves) money that banks keep within the bank, outside of circulation |

|

required reserves |

the fraction of money a bank is required to put aside and not use for loans or any other purpose, usually required by banking regulations; this fraction is based on the amount of money that has been deposited into the bank, such as 10 percent of all deposits. |

|

demand deposits |

deposits placed into banks that a bank must return to the account holder on demand; checking accounts are examples of demand deposits because the bank must allow you to withdraw it or use it at any time. |

|

the transactions motive |

when people hold money for the purpose of buying things |

|

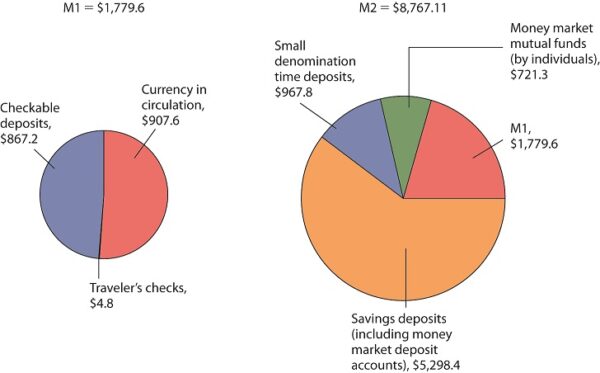

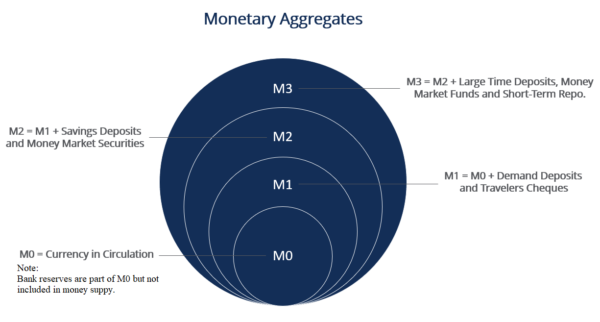

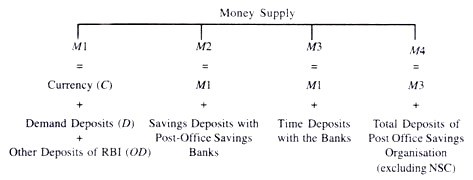

M1 |

assets that can be directly used to carry out the transactions motive of money; M1 is sometimes called “narrow money” because this is the narrowest definition of the money supply. |

|

M2 |

financial assets that aren’t directly used for a medium of exchange, but can be converted into cash or a checking account; M2 is sometimes called “near money” because it is nearly as liquid as M1, but not quite as liquid. |

|

money supply |

the total amount of money in an economy that can carry out the transactions motive; in most countries, the money supply is either the monetary aggregate M1 or M2 |

|

monetary aggregates |

an overall measure of the money supply that includes different forms of money which are categorized based on liquidity; the most commonly used monetary aggregates are M1 and M2 |

|

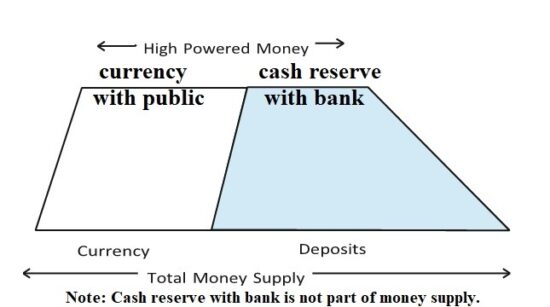

monetary base M0 |

(Also called high powered money) the sum of currency in circulation and bank reserves held in vaults; only part of the monetary base (currency in circulation) is counted in the money supply. |

|

commodity money |

money that has intrinsic value in other uses; a tangible asset that circulates as money. Examples of commodity money include gold, silver, tobacco, grain, platinum, etc. Gold has historically been the most popular and efficient commodity money used throughout history. |

|

fiat money |

money which is declared to be legal tender but has no intrinsic value and is not backed by (not legally defined by convertibility into) any tangible commodity such as gold, silver, etc. Fiat money is money by decree or proclamation. It derives its value from the perceived authority and creditworthiness of the issuer (national government – central bank of the respective country); paper money is fiat money because its value for its use as a currency is far higher than the intrinsic value of a small scrap of paper. |

|

commodity backed money |

money that has no inherent value, but it has a value guaranteed by a promise that it can be converted into something of value like gold |

|

central bank |

a banking organization that is usually independent of government, responsible for implementing a country monetary policy and for the function of issuing currency. |

|

currency |

notes and coins issued by the central bank or government serving as legal tender for trade. |

|

fiscal policy |

the deliberate use of the government’s revenue – raising (taxation) and spending activities in an effort to influence the behaviour of certain macroeconomic variables such as total employment. |

|

monetary policy |

an attempt to influence the economy by operating on such monetary variables as the quantity of money and the rate of interest. The nation’s central bank is usually involved with monetary policy. |

|

seigniorage |

seigniorage revenue is the net revenue derived for governments from the issuing of coins and bank notes. It is the difference between interest earned on the issuance of money and the costs associated with the producing and distributing bank notes & coins. Unlike the seigniorage for coins, bank note seigniorage is collected in instalments over a period of years due to paper money’s short life span (i.e., damaged notes) and the future liability to government of redeeming the currency. |

|

Bank rate (discount rate) |

Bank rate, also known as discount rate, is the rate of interest which a central bank charges on its loans and advances to a commercial bank. |

|

Funds rate |

The interest rates at which banks lend to each other overnight in order to maintain reserve requirements is known as funds rate. |

_______

_______

Various Words about Money:

Many of the words we associate with money today come from ancient uses of currency. Examining where these words came from helps us understand how currency systems developed.

Buck – Early settlers in North America relied heavily on the skin of the deer for trade. Each skin was referred to as a buck.

Pecuniary – This modern word means, “relating to money.” It comes from the Latin word pecus, which means cattle.

Fee – This word comes from the German word for cattle, vieh.

Shell out – The use of shells as currency among Native Americans, and, later, the European colonists, led to the phrase “shell out,” meaning “to pay.”

Salary – This is another money-related word we got from the Romans. At one point, Roman soldiers were paid part of their wages in salt. The Latin word salarium means “of salt.”

Dollar – A count in a Czechoslovakian town called Jachymov started minting silver coins in 1519. The coins were known as talergroschen, which was eventually shortened to talers. They spread throughout Europe, and today, many nations have currency named for some variation of the word taler, including the American “dollar.”

______

Slang terms for money:

Slang terms for money often derive from the appearance and features of banknotes or coins, their values, historical associations or the units of currency concerned. Within a language community, some of the slang terms vary in social, ethnic, economic, and geographic strata but others have become the dominant way of referring to the currency and are regarded as mainstream, acceptable language (for example, “buck” for a dollar or similar currency in various nations including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Nigeria and the United States).

India:

In India slang names for coins are more common than the currency notes. For 5 paisa (100 paisa is equal to 1 Indian rupee) it is panji. A 10 paisa coin is called dassi and for 20 paisa it is bissi. A 25 paisa coin is called chavanni (equal to 4 annas) and 50 paisa is athanni (8 annas). However, in recent years, due to inflation, the use of these small value coins has declined, and so has the use of these slang terms. The more prevalent terms now (particularly in Mumbai and in Bollywood movies) are peti for a Lakh (Rs. 100,000) and khokha for a Crore (Rs. 10,000,000) and tijori for 100 crores (Rs. 1,000,000,000). Peti also means “suitcase”, which is the volume needed to carry a Lakh of currency notes. Tijori means a large safe or a cupboard, which would be the approximate space required to store that money in cash form. Because of the real estate boom in recent times, businessmen also use the terms ‘2CR’ or ‘3CR’ referring to two crores and three crores respectively.

United States:

General terms include:

- bread

- bucks

- cheddar

- dough

- greens

- jello

- loot

- moolah

- paper

- samolians or simoleons

- smackers

- smackeroonies

- stash

- rack

- guap

U.S. coinage nicknames reflect their value, composition and tradition:

- The one-cent coin ($0.01 or 1¢) is commonly called a penny due to historical comparison with the British penny. Older U.S. pennies, prior to 1982, are sometimes called “coppers” due to being made of 95% copper. Pennies dated 1909–1958, displaying wheat stalks on the reverse, are sometimes called “wheaties” or “wheat-backs”, while 1943 steel wheat cents are sometimes nicknamed “steelies”.

- The five-cent coin ($0.05 or 5¢) is commonly called a nickel due to being made of 25% nickel since 1866. Nickels minted between 1942 and 1945 are nicknamed ‘war nickels’ owing to their different metal content, removing the nickel for a mixture of silver, copper and manganese.

- The dime coin ($0.10 or 10¢) is worth ten cents.

- The quarter coin ($0.25 or 25¢) is worth twenty-five cents. A quarter used to be called two-bits (see below), but this is falling out of use.

- The half ($0.50 or 50¢) is worth fifty cents.

Dimes and quarters used to be sometimes collectively referred to as “silver” due to their historic composition of 90% silver prior to 1965.

A bit is an antiquated term equal to one eighth of a dollar or 12+1⁄2 cents, after the Spanish 8-Real “piece of eight” coin on which the U.S. dollar was initially based. So “two bits” is twenty-five cents; similarly, “four bits” is fifty cents. Rarer are “six bits” (75 cents) and “eight bits” meaning a dollar. These are commonly referred to as two-bit, four-bit, six-bit and eight-bit.

Actually, money is so important that people came up with dozens of ways to talk about it throughout the ages. Emerging in the US, the UK or elsewhere, slang words for money became a huge part of the language we use.

______

______

Section-2

Introduction to money:

Money is one of the fundamental inventions of mankind. It has become so important that the modern economy is described as the money economy. The modern economy cannot work without money. Even in the early stages of economic development, the need for exchange arose. At first, the family or village was a self-sufficient unit. But later on, with the development of agriculture and application of the division of labor—that is, the division of the society into agriculturists, carpenters, merchants, and so on—the need for exchange arose. Exchange took place first in the form of barter. Barter is the direct exchange of goods for goods. Barter is a system of trading without the use of money. At first, when the wants of men were few and simple, the barter system worked well. But as days passed by, it was found to be unsuitable. It has many difficulties.

Difficulties of Barter:

The barter economy presents many difficulties:

-1. Absence of double coincidence of wants:

Barter requires a double coincidence of wants. That is, one must have what the other man wants, and vice versa. This is not always possible. For example, say I want a cow. You must have it. If you want a horse in return, I must have it. But if I do not have it, exchange cannot take place. So, I should go to a person who has a horse, and I must have what he wants. All of this means a lot of inconvenience. But money overcomes these difficulties. If I have an object, I can sell it for some price. I get the price in money. With that, I can buy whatever I want.

-2. No standard of measurement:

A barter market theoretically requires a value being known of every commodity, which is both impractical to arrange and impractical to maintain. If all exchanges go ‘through’ an intermediate medium, such as money, then goods can be priced in terms of that one medium. The medium of exchange allows the relative values of items in the marketplace to be set and adjusted with ease. This is a dimension of the modern fiat money system referred to as a unit of account or measure of value. Barter provides no standard of measurement. In other words, it provides no measure of value.

-3. Absence of subdivision:

Sometimes it will be difficult to split up commodities into parts. They will lose their value if they are subdivided. For example, say a man wants to sell his house and buy some land, some cows, and some cloth. In this case, it is almost impossible for him to divide his house and barter it for all the above things. Again, suppose a man has diamonds. If he divides them, he will make a great loss. A barter transaction requires that both objects being bartered be of equivalent value. A medium of exchange is able to be subdivided into small enough units to approximate the value of any good or service.

-4. Difficulty of storage:

Money serves as a store of value. In the absence of money, a person has to store his wealth in the form of commodities, and they cannot be stored for a long period. Some commodities are perishable, and some will lose their value.

-5. No transactions over time:

A barter transaction typically happens on the spot or over a short period of time. It is impossible to make payments in instalments and difficult to make payments at a later point in time.

All the difficulties of barter were overcome with the introduction of money. Despite the long list of limitations, the barter system has some advantages. It can replace money as the method of exchange in times of monetary crisis, such as when the currency is either unstable (e.g., hyperinflation or deflationary spiral) or simply unavailable for conducting commerce. It can also be useful when there is little information about the credit worthiness of trade partners or when there is a lack of trust.

_____

Medium of exchange:

In economics, a medium of exchange is any item that is widely acceptable in exchange for goods and services. In modern economies, the most commonly used medium of exchange is currency. The origin of “mediums of exchange” in human societies is assumed to have arisen in antiquity as awareness grew of the limitations of barter. The form of the “medium of exchange” follows that of a token, which has been further refined as money. A “medium of exchange” is considered one of the functions of money. The exchange acts as an intermediary instrument as the use can be to acquire any good or service and avoids the limitations of barter; where what one wants has to be matched with what the other has to offer. Most forms of money are categorised as mediums of exchange, including commodity money, representative money, cryptocurrency, and most commonly fiat money. Representative and fiat money most widely exist in digital form as well as physical tokens, for example coins and notes.

_

Examples of Mediums of Exchange:

The Island of Yap:

In 1903, an American anthropologist by the name of William Henry Furness III visited the island. He found the islanders used a currency that was large, solid, thick, stone wheels, ranging in diameter from a foot to twelve feet, having in the centre a hole varying in size with the diameter of the stone, wherein a pole may be inserted sufficiently large and strong to bear the weight and facilitate transportation. An interesting aspect of the stones was that they were made from limestone found on an island some 400 miles distant. They were originally quarried and shaped on that island and brought to Yap by venturesome native navigators, in canoes and on raft. Also interesting was that it was not necessary for owners to physically possess the stones. After concluding bargains that involved too many stones to be conveniently moved, its new owners were quite content to accept the bare acknowledgment of ownership and without so much as a mark to indicate the exchange, the coin remains undisturbed on the former owner’s premises.

Cigarettes as a Currency in Prisoner of War Camps:

R.A. Radford was a British prisoner of war in a German camp during World War 2. His article “The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp” describes the use of cigarettes as a currency in these camps. Radford describes how all prisoners would receive equal supplies of all rations including cigarettes. Everyone receives a roughly equal share of essentials; it is by trade that individual preferences are given expression and comfort increased. All at some time, and most people regularly, make exchanges of one sort or another. “Cigarettes rose from the status of a normal commodity to that of currency … Although cigarettes as currency exhibited certain peculiarities, they performed all the functions of a metallic currency as a unit of account, as a measure of value and as a store of value, and shared most of its characteristics. They were homogeneous, reasonably durable, and of convenient size for the smallest or, in packets, for the largest transactions.”

Precious Metals as Mediums of Exchange:

While large stones and cigarettes make entertaining examples of items that can be used as a medium of exchange, coins made of precious metals such as gold and silver have been the dominant format for money for most of its history. Precious metals were adopted as mediums of exchange because they contained many of the features that made such mediums work well.

-1. Coins made of precious metals were portable and easy to use.

-2. The precious metal content of coins could be standardised and checked.

-3. The metals generally had their own separate value for use as jewellery or ornaments, so the coins could still have a value even if they ceased to be accepted purely as a medium of exchange.

-4. The fact that metals were difficult to extract meant that the supply of such metals was usually stable. Large fluctuations in the supply of a medium of exchange will limit its usefulness.

Despite these advantages, many different decisions had to be taken before precious metals could be used as a workable currency system.

_

Government Money:

Because of the inefficiency of barter, mediums of exchange sometimes emerged as an evolutionary process in which people decided that the use of some agreed “token” to facilitate transactions would be an improvement. However, a number of questions have to be resolved before a monetary system can be put in place.

-1. Who decides which tokens will be used as money?

-2. Who controls the supply of money?

-3. Who prevents counterfeit of money?

In practice, most of the monetary systems that have existed have been controlled by governments as opposed to emerging spontaneously from private markets. Charles Goodhart’s 1998 paper “Two Concepts of Money” provides evidence that the relationship of the state, the governing body, to currency in all its roles has almost always been close and direct. He explains the key roles governments have played in introducing money, in enforcing its use as legal tender and in generating demand for it via requiring payment of taxes in money. The introduction of currency also made it much more convenient for governments to collect taxation. Kings traditionally required resources to fund their armies, justice systems, palaces and so on. Prior to the existence of currency, kings could request, for example, 10 percent of everyone’s output and then use barter to exchange stuff they didn’t need for stuff they did need. But this kind of system creates lots of complications. At what point in the year does the king collect his share and where does he store it all? How would the king collect ten percent of the output of a barber or a playwright? The introduction of currency thus made it much easier to finance government operations. Requiring that taxation be paid in the legal tender created an important source of demand for the currency and also restricted its supply: A government running a balanced budget would receive as much currency as it created so it was not increasing the total supply of currency.

______

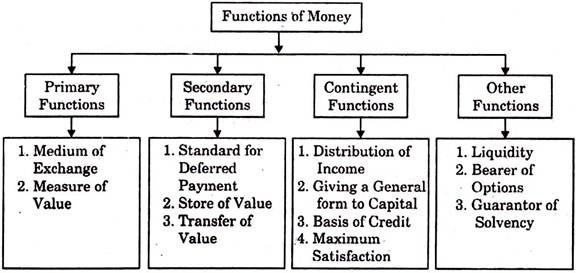

The term money refers to an object that is accepted as a mode for the transaction of goods and services in general and repayment of debts in a particular country or socio-economic framework. Traditionally, economists considered four main functions of money, which are a medium of exchange, a measure of value, a standard of deferred payment, and a store of value. Money can be in various forms, such as notes, coins, credit and debit cards, and bank checks.

There are two important things to note about money. First, Money has been defined in terms of functions it performs. That is, money is anything which performs the functions of money. Second, any essential requirement of any kind of money is that it must be generally acceptable to every member of the society. Money has a value for ‘A’ only when he thinks that ‘B’ will accept it in exchange for goods. And money is useful for ‘B’ only when he confident that ‘C’ will accept it in exchange for goods or for settlement of debts. General acceptability is not a physical quality possessed by a good. General acceptability is a social phenomenon and is conferred upon a good when the society by law or convection adopts it as a medium of exchange. Since general acceptability is the fundamental characteristic of money, in simple words, money may be defined as anything which is generally acceptable by the people in exchange of goods and services or in repayment of debts. The status of a particular form of money always depends on the status ascribed to it by humans and by society. For instance, gold may be seen as valuable in one society but not in another or that a bank note is merely a piece of paper until it is agreed that it has monetary value.

Money is a concept which we all understand but which is difficult to define in exact terms. This is because it fulfills many functions and comes in many forms each of them providing a criterion of moneyness. For this reason, Prof. Walker defines money as ‘‘Money is what money does’’. By this, he refers to the functions of money. Money performs many functions in a modern economy. One of the traditional definitions of Money calls it “a unit of account, a means of payment and a store of value”.

Professor Coulborn defines money as “the means of valuation and of payment; as both the unit of account and the generally acceptable medium of exchange.” These are the functional definitions of money because they define money in terms of the functions. Some economists define money in legal terms saying that “anything which the state declares as money is money.”

Professor D.H. Robertson defines money as “anything which is widely accepted in payment for goods or in discharge of other forms of business obligations.”

According to Hawtrey, “Money is one of those concepts which like a teaspoon or an umbrella, but unlike an earthquake or buttercup are definable primarily by the use or purpose which they serve.”

According to Crowther, “Money can be defined as anything that’s generally acceptable as a means of exchange and that at the same time acts as a measure and a store of value.” An important point about this definition is that it regards anything that is generally acceptable as money. Thus, money includes coins, currency notes, cheques, Bills of Exchange, and so on.

According to Dr Alfred Marshall, “Money constitutes all those things which are at any time and place generally accepted without doubt or specially enquiry as a means of purchasing commodities and services and of defraying expenses”.

According to Prof G D H Cole, “Money is anything that is habitually and widely used as a means of payment and is generally acceptable in the settlement of debt.”

It is not always easy to define money.

_______

Money goes back a dizzyingly long way in Indo-European civilization. Well before the invention of minted coins in the Lydian cities of the Aegean in the 7th century BCE, writings from the Sumerian civilization at Ur in the 3rd millennium BCE refer to documents mentioning silver struck with the head of Ishtar. The mother-goddess and symbol of fertility, Ishtar was also the goddess of death. So from the very outset, money’s ambivalence reflects the ambiguity of its social function: an instrument of cohesion and pacification in the community, it is also at the center of power struggles and a source of violence. Money towers over the market economy as we know it from so high and so far that its shadow throws suspicion on the prevailing economic wisdom, which incidentally also creates unease within the profession itself. After all, did not Hahn assert that the perplexing difficulty of the theory of value lay in the inability to account for the universality and durability of money? Economists cannot therefore regard the history of money as a sort of “natural” history which should immediately make sense. The OECD views money as a force driving economic and social change. This position is incompatible with the neutrality of money, which is the theoretical cladding for its supposed unimportance in coordinating economic actions as money is the primary standard of exchange, the fundamental institution of the market economy. This is the paradox of money in economics.

_______

We are destined to fail if we try to define ‘money’ from the viewpoint of materials or forms. Money is sometimes considered to be some commodity such as gold or silver, and it is sometimes considered to be the paper on which some numbers and figures are printed. Furthermore, it is often considered to be the only abstract number recorded in the computers used by the banks. Money changed its materials and its forms in the course of the development of economic society. As Hicks (1967) pointed out correctly, therefore, we must define ‘money’ from the viewpoint of its function. Usually, the economists define ‘money’ as the ‘generally accepted means of payments’, and as a result it is said that ‘money’ must have the following three functions.

-1. Means of payments (or means of exchange)

-2. Measure of value (or unit of calculation)

-3. Means of store of value

This is the conventional definition of ‘money’ in Economics. As Hicks (1967) noted, this definition has somewhat paradoxical nature, because it means that ‘money’ is what is considered to be money by a lot of people in a society. It may be worth noting that the first function is primary, and other two functions are derived from the first function. That is to say, money is used as the measure of value and the means of store of value because it is generally accepted as the means of payments or exchange. Money to be used as a medium of exchange must be universally acceptable. All people must accept a thing as money. Or the government should give it legal sanction. And to be used as a store of value, money should have stability of value. In other words, the value of money should not change often. Since ancient times, the enigmatic properties of money have fascinated philosophers, and the philosophical and metaphysical speculations on money abound.

_

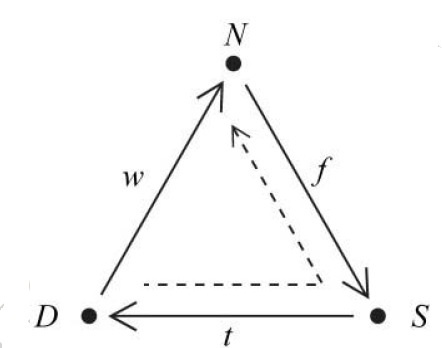

In standard economic theory, the necessity of money is usually explained by using figure below, which is an illustration of the so called ‘Wicksell’s problem’.

Suppose that there are three economic agents, D(Denmark) who has the commodity w(wheat), S (Sweden) who has the commodity t (timber), and N (Norway) who has the commodity f (fishes). Suppose, furthermore, that D wants t, S wants f, and N wants w. In this case, any exchange in barter is impossible because there is no double coincidence of the wants. However, the indirect exchanges become possible if one of the commodities, for example, w, is used as a ‘generally accepted means of payments’, that is, money. In this case, S receives w from D in exchange for t, and then S receives f from N in exchange for w. In this example, a commodity w became the ‘commodity money’. But, what kind of commodity is likely to become commodity money? Menger (1892) considered this problem, and his answer was as follows. “The commodity with the highest saleability or marketability will be accepted as money by the society.” Historically such a commodity was gold or silver. This is a semi theoretical/semi historical consideration of the origin of money. Needless to say, in modern society money is not commodity money but paper money and/or credit money. But it is true that they are still the commodities with the highest saleability/marketability in modern society.

________

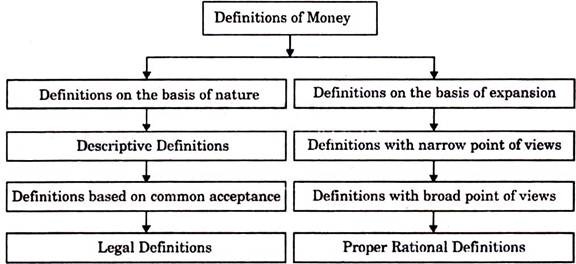

Definition of Money:

There is much difference in opinions of scholars regarding the ‘definition of money’. Someone has based the definition of money on the universal acceptance; whereas someone else has taken its function as the central issue in the definition. The definitions of money can be classified as follows:

_

Definitions on the basis of nature of money can be classified into following three groups:

-1. Descriptive or Functional Definitions:

This category includes definitions of those scholars who stated functions of money in their definitions.

Some important definitions of this category are given below:

(1) According to Crowther, “Money is anything that is commonly used and generally accepted as means of exchange and at the same time acts as measure and store of value.”

(2) According to Prof. Thomas, “It is a means to an end not for its own sake but as a means of obtaining-other’s articles or commanding the service of others”.

(3) According to Coulborn, “Money may be defined as the means of valuation and payment.”

(4) According to Nogaro, “Money is a commodity which serves as an intermediary in exchange and as a common measure of value.”

(5) According to Hartle Withers, “Money is what money does.”

(6) According to Whitelesy, “If a particular unit is commonly employed to state values, exchange goods and services or perform other money functions, than it is money whatever its legal or physical characteristics.”

Although the above definitions are practical, they describe money in place of defining it. There is radical difference in ‘description’ and ‘definition’. These definitions don’t claim any universal acceptance or recognition of governments. So even if these definitions are accepted in practice, they can’t be given recognition.

-2. Definitions Based on Common Acceptance:

It is an essential characteristic of money that it is commonly accepted by the common people in return for the goods and services. So, some scholars have defined money on the basis of acceptance.

Some important definitions of this category are given here:

(1) According to Marshal, “Money includes all those things which are at given time or place generally current without doubt or special enquiry as a means of purchasing commodities or services and of defraying expenses.”

(2) According to Robertson, “Money is anything which is widely acceptable in discharge of obligation.”

(3) According to Seligman, “Money is one thing that possesses general acceptability.”

(4) According to Ely, “Anything that passes freely from hand to hand as a medium of exchange and is generally received in final discharge of debts.”

(5) According to Prof. Keynes, “Money itself is that by delivery of which debt contracts and price contracts are discharged and in the shape of which a store of general purchasing power is held.”

(6) According to G.D.H. Cole, “Money is simply purchasing power— something which buys things, it is anything which is habitually and widely used as a means of payment and is generally acceptable in the settlement of debts.”

(7) According to R.P. Kent. “Money is anything which is commonly used and generally accepted as a medium of exchange or as a standard value.”

(8) According to (roger miller) “Anything which is generally accepted in payment for the goods and services or the repayment of debts is money”

It is evident from all above definitions that a common acceptance is a chief characteristic of money. But just describing qualities can’t be a complete definition. On the basis of the above definitions credit instruments can’t be considered as money since they are not accepted everywhere.

-3. Legal Definitions:

Definitions based on state principles have been kept under this category. According to this principle only such a thing can be money which has been declared legally by the government. This category includes ideas of Prof. Knapp from Germany and British Economist Hartle.

(1) According to Knapp, “Anything which is declared money by state becomes money.”

(2) Hartle has also initially accepted the definitions given by Knapp, but he has amended this definition saying, “Money should not be defined only in terms of recognition by the government, but also as a unit of settlement of transactions.”

__

Definitions given on the Basis of Expansion:

There are three views regarding the meaning of money on the basis of expansion:

-1. Definitions with Narrow Points of View:

The definition given by Robertson is kept in this category. Robertson and his associates held that “A commodity which is used to denote anything which is widely accepted in payment of goods or in discharge of other business obligations.”

If this definition is analysed, gold is the only thing which is acceptable to all countries for replacement. In this condition, money formed from gold or silver alone can be included in the definition of money. So, most of the economists held, the definition given by Robertson to be narrow.

-2. Definitions with Broad Points of View:

Definition given by Hartle Withers can be included in this category! According to him, “Money is what money does.”

This definition is descriptive as well as universal. This definition can be termed as ‘everything in something’. According to this definition not only metals or currencies but also cheques, bill of exchanges, hundies and other credit instruments are included in money. But some economists consider that this definition is far more universal (broad) than what is needed. According to this definition credit instruments are also money, but nobody can be compelled to accept it for repayment.

-3. Proper Definition:

On making a careful study of various definitions, it is found that some economists have centered their attention on the acceptance of money, while some others have based their definitions on functions what it does. To know the form of money, it can be defined as follows:

“Money is something which is accepted freely and widely as a medium of exchange; measuring value; final repayment of loans and accumulating values.”

______

Definitions Based on Viewpoints of Economists:

Harry G. Johnson has presented four viewpoints regarding the definition of money.

These include:

(1) Traditional Approach:

According to this viewpoint money is considered according to its function. So, all those things which act as money can be called money. On this basis, currencies and demand deposits are included in money. In this category Hartle Withers, Keynes, Kent, Crowther etc. get place for their definitions.

(2) Chicago Approach:

Economist of Chicago University has made the definition of money universal by accepting the traditional approach and at the same time including fixed term deposits and savings accounts deposits of commercial banks.

According to this approach:

Money = Currency + Demand Deposits + Fixed Deposits + Saving Bank Deposit.

(3) Gurley and Shaw Approach:

This approach includes savings deposits with non-banking financial institutions, debenture and bonds to Chicago approach.

So, according to this approach:

Money = Currency + Demand Deposits + Fixed Deposits + Saving Bank Deposits + Saving Deposits with Non-banking Financial Institutions, shares, debentures and bonds.

(4) Central Bank Approach:

According to this approach all kinds of credits are included in money. That is why; in the monetary policies of the Central Bank the amount of gross credit is considered.

Redcliff has also said, “Money means credits forwarded by various sources.”

Considering all these approaches it is evident that ‘Proper Definition’ which has already been defined is the best.

_____

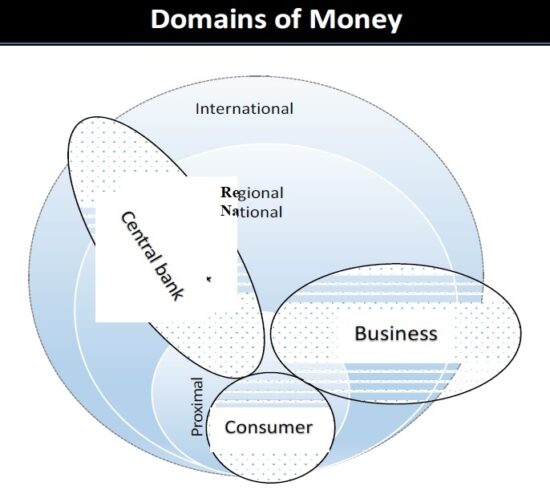

Locality:

The definition of money says it is money only “in a particular country or socio-economic context”. In general, communities only use a single measure of value, which can be identified in the prices of goods listed for sale. There might be multiple media of exchange, which can be observed by what is given to purchase goods (“medium of exchange”), etc. In most countries, the government acts to encourage a particular form of money, such as requiring it for taxes and punishing fraud.

Some places do maintain two or currencies, particularly in border towns or high-travel areas. Shops in these locations might list prices and accept payment in multiple currencies. Otherwise, foreign currency is treated as a financial asset in the local market. Foreign currency is commonly bought or sold on foreign exchange markets by travellers and traders.

Communities can change the money they use, which is known as currency substitution. This can happen intentionally, when a government issues a new currency. For example, when Brazil moved from the Brazilian cruzeiro to the Brazilian real. It can also happen spontaneously, when the people refuse to accept a currency experiencing hyperinflation (even if its use is encouraged by the government).

The money used by a community can change on a smaller scale. This can come through innovation, such as the adoption of cheques (checks). Gresham’s law says that “bad money drives out good”. That is, when buying a good, a person is more likely to pass on less-desirable items that qualify as “money” and hold on to more valuable ones. For example, coins with less silver in them (but which are still valid coins) are more likely to circulate in the community. This may effectively change the money used by a community.

The money used by a community does not have to be a currency issued by a government. A famous example of community adopting a new form of money is prisoners-of-war using cigarettes to trade.

______

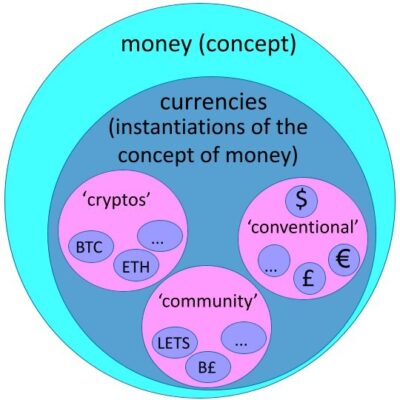

Various money types:

-1. Fiat Money

Examples: Banknotes (paper money) and coins

Fiat money (fiat currency) is money whose value is not based on its inherent value but is based on an authoritative decision (fiat) by the governing body. The government declares it as legal tender and it must then be accepted as a form of payment everywhere. Due to not having an intrinsic value, a partially destroyed bill can be replaced by the Federal Reserve Bank. On the other hand, commodity money cannot be.

-2. Commodity Money

Examples: Precious metals (i.e., gold), salt, beads, alcohol

Unlike fiat currency, the value of commodity money is intrinsic; its value comes from the commodity it is made from. If the money is destroyed, it cannot be replaced. It is also probably the earliest form of money. These commodities are used as a medium of exchange and gain their value from the scarcity of the items. The use of this type of money is like using the barter system where goods and services are exchanged for the like. Unlike the barter system, using commodity money functions as a unit of account that allows you to compare the worth of goods and services.

-3. Representative Money

Examples: Certificates, token coins

Representative money, like fiat money, has no value of its own. Unlike fiat money, it is backed by a commodity. As a commodity-back money, it could be exchanged for precious metals (like gold) held within a bank vault. It was easier to carry a certificate around rather than a chest full of gold.

-4. Fiduciary Money

Examples: Checks, bank drafts

Deriving from the Latin word fiducia, to trust, fiduciary money works on the promise and trust that it will be exchanged for fiat or commodity money by the issuer (bank). People are not required to take it as a form of payment because it is not a government-ordered legal tender. People can use fiduciary money just like regular fiat or commodity money as long as they are confident that the promise will not be broken.

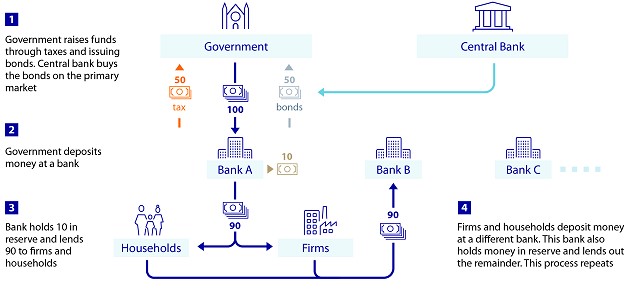

-5. Commercial Bank Money

Example: Funds in a checking account

Commercial money (also known as demand deposits) is a claim against a bank for the purchase of goods and services (through the means of withdrawing in person, check, ATMs, or online banking). It is a debt-created currency by the bank. They create more money through a process called fractional-reserve banking. In this, only a certain percentage of money the bank “has” is held within it. The other percent is given to others in the form of loans, in doing so, the bank makes back more money from the interest and fees charged to customers. In short, the bank is loaning out the money you deposit to give others debt and create more money from the interest placed on it.

______

Leper colony money:

Leper colony money was special money (scrip or vouchers) which circulated only in leper colonies (sanatoriums for people with leprosy) due to the fear that money could carry leprosy and infect other people. The original reason for leper colony money was the prevention of leprosy in healthy persons. However, leprosy is not easily transmitted by casual contact or objects; actual transmission only happens through long-term, constant, intimate contact with leprosy sufferers and not through contact with everyday objects used by sufferers. Special leper colony money was used between 1901 and around 1955. In 1938, Dr. Gordon Alexander Ryrie in Malaysia proved that the paper money was not contaminated with leprosy bacteria, and all the leper colony banknotes were burned in that country.

_______

Inside and Outside Money:

Money is an asset that serves as a medium of exchange.

Outside money is money that is either of a fiat nature (unbacked) or backed by some asset that is not in zero net supply within the private sector of the economy. Thus, outside money is a net asset for the private sector. The qualifier outside is short for (coming from) outside the private sector.

Inside money is an asset representing, or backed by, any form of private credit that circulates as a medium of exchange. Since it is one private agent’s liability and at the same time some other agent’s asset, inside money is in zero net supply within the private sector. The qualifier inside is short for (backed by debt from) inside the private sector.

Money which is an asset to the person or firm holding it, but is also a liability for somebody else in the economy. As an easy way to remember whether money is “inside” or “outside” money ask first where the liability resides. If the liability resides inside the private sector then the money is inside money. If the liability resides outside the private sector then the money is outside money. For instance, a bank deposit is a liability of the private bank that issues it. One of the most common examples of inside money is the deposits that customers make at banks. These deposits form the basis for the bank being able to respond to the needs of others in the community who are in need of loans for cars, mortgages, and other loan. Inside money is contrasted with outside money, where the asset of the holder is not balanced by a liability for some other party. Bank balances, for example, are clearly inside money, while gold coinage is outside money. A rise in the real value of inside money does not increase the aggregate wealth of the economy, but redistributes it between the issuers and the holders of money.

______

Understanding Money:

Money is an economic unit that functions as a generally recognized medium of exchange for transactional purposes in an economy. Money provides the service of reducing transaction cost, namely the double coincidence of wants. Money originates in the form of a commodity, having a physical property to be adopted by market participants as a medium of exchange. Money can be: market-determined, officially issued legal tender or fiat moneys, money substitutes and fiduciary media, and electronic cryptocurrencies.

_

Money is a liquid asset used in the settlement of transactions. It functions based on the general acceptance of its value within a governmental economy and internationally through foreign exchange. The current value of monetary currency is not necessarily derived from the materials used to produce the note or coin. Instead, value is derived from the willingness to agree to a displayed value and rely on it for use in future transactions. This is money’s primary function: a generally recognized medium of exchange that people and global economies intend to hold, and are willing to accept as payment for current or future transactions.

_

Money is a medium of exchange, a measure of value, a store of value, and a standard of deferred payments.

-1. Medium of exchange:

The most important function of money is that it acts as a medium of exchange. When money is used to intermediate the exchange of goods and services, it is performing the function of a medium of exchange. It thereby avoids the inefficiencies of a barter system, such as the dependence on the occurrence of a coincidence of wants. To be widely acceptable, a medium of exchange should have stable purchasing power. It should therefore possess the following characteristics:

Valuation of common assets

Constant utility

Low cost of preservation

Transportability

Divisibility

High market value in relation to volume and weight

Recognizability

Resistance to counterfeiting

Gold was long popular as a medium of exchange and store of value because it was inert and was convenient to move because even small amounts of it had considerable value. Gold also had a constant value due to its special physical and chemical properties, which made it cherished by men.

-2. Measure of value:

Money acts as a common measure of value. It is a unit of account and a standard of measurement. Whenever, we buy a good in the market, we pay a price for it in money. And price is nothing but value expressed in terms of money. So we can measure the value of a good by the money we pay for it. Just as we use yards and meters for measuring length, and pounds for measuring weights, we use money for measuring the value of goods. It makes economic calculations easy. To function as a measure of value and unit of account, whatever is being used as money must meet these characteristics:

-It must be divisible into smaller units without loss of value. For example, precious metals can be coined from bars, or melted down into bars again.

-It must be fungible. In other words, one unit or piece must be perceived as equivalent to any other. One dollar note is equivalent to any one dollar note. This is why diamonds, works of art, or real estate are not suitable as money.

-It must be countable. A unit of account is countable and subject to mathematical operations. You can easily add, subtract, divide, and multiply units. This allows people to account for profits, losses, income, expenses, debt, and wealth. It must have a specific weight, measure, or size in order to be verifiably countable. For instance, coins are often milled with a reeded edge, so that any removal of material from the coin (lowering its commodity value) will be easy to detect.

-3. Store of value:

A man who wants to store his wealth in some convenient form will find money admirably suitable for the purpose. It acts as a store of value. Suppose the wealth of a man consists of a thousand cattle. He cannot preserve his wealth in the form of cattle. But if there is money, he can sell his cattle, get money for that and can store his wealth in the form of money. To act as a store of value, money must be able to be reliably saved, stored, and retrieved. Moreover, it must be predictably usable as a medium of exchange when it is retrieved. The value of the money must also remain stable over time. Put simply, money acting as a store of value allows its owner to transfer real purchasing power from the present to the future. Some have argued that inflation, by reducing the value of money, diminishes its ability to function as a store of value.

-4. Standard of deferred payments:

Money is used as a standard for future (deferred) payments. It forms the basis for credit transactions. Business in modern times is based on credit to a large extent. This is facilitated by the existence of money. In credit, since payment is made at a future date, there must be some medium which will have as far as possible the same exchange power in the future as at present. If credit transactions were to be carried on the basis of commodities, there would be a lot of difficulties and it will affect trade. Money can function as a “standard of deferred payment”, which means that its status as legal tender allows it to function for the discharge of debts. Debt is the money you owe, while credit is money you can borrow. You create debt by using credit to borrow money.

_

Money is one of the most fundamental inventions of mankind. Every branch of knowledge has its fundamental discovery. In mechanics, it is the wheel; in science fire; in politics the vote. Similarly, in economics, in the whole commercial side of man’s social existence, money is the essential invention on which all the rest is based. Money is indispensable in an economy, whether it is capitalistic or socialistic. Price mechanism plays a vital role in capitalism. Production, distribution, and consumption are influenced to a great extent by prices, and prices are measured in money. Even a socialist economy, where the price system does not play so important a role as under capitalism, cannot do without money. For a while, the socialists talked of ending money, i.e., abolishing money itself, because they considered money as an invention of the capitalists to suppress the working class. But later on they found that even under a system of planning, economic accounting would be impossible without the help of money.

_

In the early stages of civilization, different people used different things as money. Cattle, tobacco, shells, wheat, tea, salt, knives, leather, animals such as sheep, horses and oxen, and metals like iron, lead, tin, and copper have been used as money. Gradually, precious metals such as gold and silver replaced other metals such as iron, copper, and bronze as money. Now paper is used as money. Almost all countries in the world today have paper money. We may describe one more form of money; that is, bank deposits that goes from person to person by means of cheques.

_

Although money can take an extraordinary variety of forms, there are really only two types of money: money that has intrinsic value and money that does not have intrinsic value.

Commodity money is money that has value apart from its use as money. Mackerel in federal prisons is an example of commodity money. Mackerel could be used to buy services from other prisoners; they could also be eaten. Gold and silver are the most widely used forms of commodity money. Gold and silver can be used as jewellery and for some industrial and medicinal purposes, so they have value apart from their use as money. The first known use of gold and silver coins was in the Greek city-state of Lydia in the beginning of the seventh century B.C. The coins were fashioned from electrum, a natural mixture of gold and silver.

One disadvantage of commodity money is that its quantity can fluctuate erratically. Gold, for example, was one form of money in the United States in the 19th century. Gold discoveries in California and later in Alaska sent the quantity of money soaring. Some of this nation’s worst bouts of inflation were set off by increases in the quantity of gold in circulation during the 19th century. A much greater problem exists with commodity money that can be produced. In the southern part of colonial America, for example, tobacco served as money. There was a continuing problem of farmers increasing the quantity of money by growing more tobacco. The problem was sufficiently serious that vigilante squads were organized. They roamed the countryside burning tobacco fields in an effort to keep the quantity of tobacco, hence money, under control. (Remarkably, these squads sought to control the money supply by burning tobacco grown by other farmers.)

Another problem is that commodity money may vary in quality. Given that variability, there is a tendency for lower-quality commodities to drive higher-quality commodities out of circulation. Horses, for example, served as money in colonial New England. It was common for loan obligations to be stated in terms of a quantity of horses to be paid back. Given such obligations, there was a tendency to use lower-quality horses to pay back debts; higher-quality horses were kept out of circulation for other uses. Laws were passed forbidding the use of lame horses in the payment of debts. This is an example of Gresham’s law: the tendency for a lower-quality commodity (bad money) to drive a higher-quality commodity (good money) out of circulation. Unless a means can be found to control the quality of commodity money, the tendency for that quality to decline can threaten its acceptability as a medium of exchange.

But something need not have intrinsic value to serve as money. Fiat money is money that some authority, generally a government, has ordered to be accepted as a medium of exchange. The currency—paper money and coins—used today is fiat money; it has no value other than its use as money. You will notice that statement printed on each bill: “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private.” Legal tender money is issued by the monetary authority of a country. It has legal sanction of the Government. Every individual is bound to accept legal tender money in exchange for goods and services, and in the discharge of debts.

Checkable deposits, which are balances in checking accounts, and traveler’s checks are other forms of money that have no intrinsic value. They can be converted to currency, but generally they are not; they simply serve as a medium of exchange. If you want to buy something, you can often pay with a check or a debit card. A check is a written order to a bank to transfer ownership of a checkable deposit. A debit card is the electronic equivalent of a check. Suppose, for example, that you have $100 in your checking account and you write a check to your campus bookstore for $30 or instruct the clerk to swipe your debit card and “charge” it $30. In either case, $30 will be transferred from your checking account to the bookstore’s checking account. Notice that it is the checkable deposit, not the check or debit card, that is money. The check or debit card just tells a bank to transfer money, in this case checkable deposits, from one account to another.

A negotiable instrument is a signed document that promises a sum of payment to a specified person or the assignee. Negotiable instruments are transferable in nature, allowing the holder to take the funds as cash or use them in a manner appropriate for the transaction or according to their preference. Common examples of negotiable instruments include checks, money orders, and promissory notes. Negotiable instruments do not include money. Negotiable instruments exist as an alternative to cash in instances where someone wants to promise or order the payment of a specific amount of money. Check is a negotiable instrument but not money.

What makes something money is really found in its acceptability, not in whether or not it has intrinsic value or whether or not a government has declared it as such. For example, fiat money tends to be accepted so long as too much of it is not printed too quickly. When that happens, as it did in Russia in the 1990s, people tend to look for other items to serve as money. In the case of Russia, the U.S. dollar became a popular form of money, even though the Russian government still declared the rouble to be its fiat money.

______

______

Qualities (properties) of good money:

With the ongoing fraudulent issues associated with counterfeit money, it is important to be familiar with the qualities of good money. To be able to perform the functions of money well, the money material must possess the following qualities:

-1. Acceptability – Good money is accepted by all because it serves as a medium of exchange. The material of which money is made should be acceptable to all without any hesitation. In this connection, metallic money – gold and silver are considered as good money material because they are readily acceptable to the general public due to its utility and value. The holder can use it as money or metal. He does not lose value in both.ie Apart from being used as money, these metals can also be put to other uses (e.g., making ornaments.) The essential quality of good money is that it should be acceptable to all, without any hesitation in the exchange for goods and services. Also it should have a long history of acceptance, which is why we don’t use molybdenum or rhodium.

-2. Durability – Money must be durable/long lasting. It should not lose its value with passage of time. This simply refers to the physical wear and use of money over a period of time. If some money is easily destroyed or damaged it is likely that it is fraudulent and therefore cannot be trusted. Money material must last for a long time without losing its value. Ice and fruits cannot become good money because they lose their value with the passage of time. Ice melts and fruits, wheat, corn, rice etc perish. Metals are most durable compared to other forms of money. Gold and silver do not wear out quickly, in case of money made from a paper source some wear and tear must be expected. However they can be treated as durable due to replacement by the bank.

-3. Portability – The commodity chosen as money should be easily transportable without any depreciation. Good money must be portable easily. It should have more value in small quantity. On this ground, various animals cannot be used as money. The commodity chosen as money should be easily transportable without any depreciation. i.e. should be easily transferable from one place to another for doing business and making payment. The paper money is easier to carry because it has less weight than metallic money, people can carry it around with them on a daily basis. This also allows for the ease of transaction.

-4. Scarcity – The scarcity is the quality of good money material. Good money is always scarce. Money must be limited in supply as compare to demand for it. It should be scarce enough to be valuable/ to retain its worth. The more money that is in circulation the less it is valued by the economy. Which is why we don’t use aluminium or iron or common goods such as sand or pebbles on a beach. This quality induces the people to have more and more money for meeting their basic necessities of life.

-5. Divisibility – Good money is that which could be easily sub-divided for the purchase of smaller units of the commodities, without losing any value. People will only need as much money as is necessary for their purchases, therefore it is necessary for money to be easily broken down for different types of transactions. Cow, for example, cannot function as good money because it cannot be divided without losing its value; a fraction of cow is quite different entity than a whole cow. The metallic money and paper money is divisible and therefore has public confidence

-6. Cognizability – Good money is easily recognized either by sound, sight or touch. If it is not easily recognizable, it would be difficult for the individuals to determine whether they are dealing with money or some inferior asset. Money is subject to the type of currency that is in circulation within a specific place, so if it is easily recognized it is likely to be genuine. The printing of notes is secret. The imitation is not possible, because the process of colouring and the quality of paper are always in the hands of central bank. The general public is familiar with the various kinds of notes and recognise it easily.

-7. Malleability – A good money material must be malleable i.e. capable of being melted and put to different forms/new money. A metal is melted and then coins are minted. Gold, silver, copper, etc., have this quality they can be moulded and stamped and proper designs are made on it. The money material, which can be melted, is fit for making coins. The malleable materials have impression on its face and back for recognition.

-8. Homogeneity / Uniformity – Good money must be of standardized/identical nature. The quality and quantity of its material should not undergo great change. Money should be homogeneous. Its units should be identical; they should be of equal quality and physically indistinguishable. The unit of money of the same denomination of currency must have the same purchasing power otherwise there will be confusion in buying and selling of goods and services. The colour and size of money material help the people to deal in the market and also allows for money to be counted and measured accurately. If money is not homogeneous, the individuals will not be certain of what they are receiving when they make transactions.

-9. Elasticity -The good material has the quality of elasticity. The business needs change from season to season. The supply money should be elastic. If demand of money increases its supply may be increased easily. Paper money possesses the quality of elasticity.

-10. Stability of value – The value of money should remain stable and should not change for a long period of time. If the value of money is not stable, it will not be able to function as a measure of value, as a store of value and as a standard of deferred payment. A change in its value brings change in the prices of goods and services. The public confidence is developed if value of money is stable. The money having ever-changing value is not liked by the people

-11. Storability – A good money material is that which can be store able without any depreciation. If money material is perishable then it cannot serve as a good money material as it will lose its value. A good money material is storable for meeting the future demand. The minimum space and lowest storing expenses are necessary for keeping the money material. Paper money and metallic coins have this quality of storability.

-12. Economical – It is important quality of good money that it should be made economically, unnecessary expenditure may not be wasted on its preparation. If there is heavy cost on issuing more money that is not good money. Good money is that has low cost and more supply. The cost of printing currency notes and minting coins must be lower. Paper money has this quality of economy.

-13. Effective Supervision – The good money is one that can be effectively supervised by a central monetary authority. It is of such a nature that central authority is able to keep records of the amount of money in circulation and the pattern of its distribution.

-14. Government Support: The good money material must be supported by the government. The people accept even fiat money (money issued without keeping any metallic reserves) due to the government support. The government’s backing to money creates a sense of confidence.

-15. Fungibility: It must be fungible. In other words, one unit or piece must be perceived as equivalent to any other. One dollar note is equivalent to any one dollar note. This is why diamonds, works of art, or real estate are not suitable as money.

-16. Countable: It must be countable. A unit of account is countable and subject to mathematical operations. You can easily add, subtract, divide, and multiply units. This allows people to account for profits, losses, income, expenses, debt, and wealth. It must have a specific weight, measure, or size in order to be verifiably countable. For instance, coins are often milled with a reeded edge, so that any removal of material from the coin (lowering its commodity value) will be easy to detect.

-17. Noncounterfeitability: This characteristic means that money cannot be easily duplicated. A given item cannot function as a medium of exchange if everyone is able to “print up,” “whip up,” or “make up” a batch of money any time that they want. Why would anyone accept money in exchange for a good, if they can make their own? Money that is easily duplicated ceases to be the medium of exchange.

Preventing the unrestricted duplication of money is a task that has long been relegated to government. In fact, this task is one of the prime reasons why governments exist. An economy needs government to regulate the total quantity of money in circulation. By controlling money duplication, governments are also able to control the total quantity in circulation, and this control is what gives money value in exchange.

_

So far not a single commodity has been discovered which possess all the attributes given above in their entirety. The precious metals, gold and silver by and large, possess the above mentioned qualities of good money material. It is because of this reason, that these metals have been used as money for a considerably long period of time. These have been discarded in the past in favour of paper currency and bank money. Now the notion of money has changed. The modern governments go through trial and error procedures before adopting a common medium of exchange. The main considerations for selecting a money material are general acceptability and cost of producing money. We can say that anything which command confidence of the people and is accepted as a medium of exchange is called money.

__

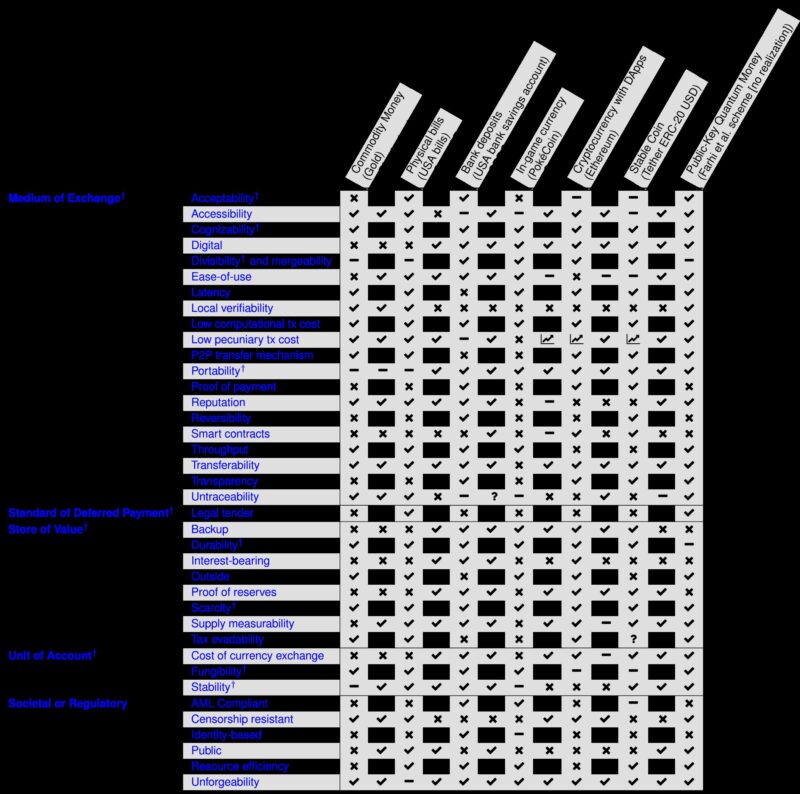

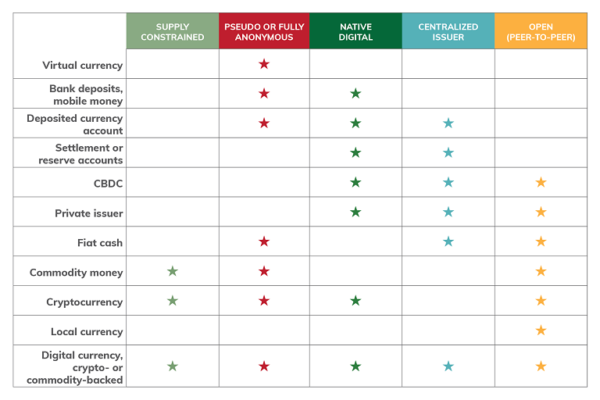

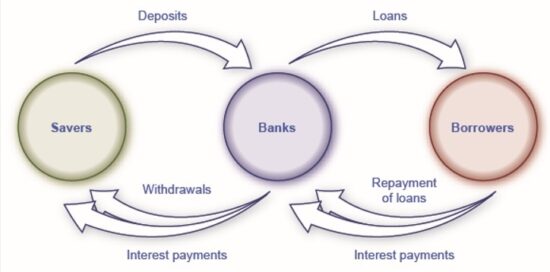

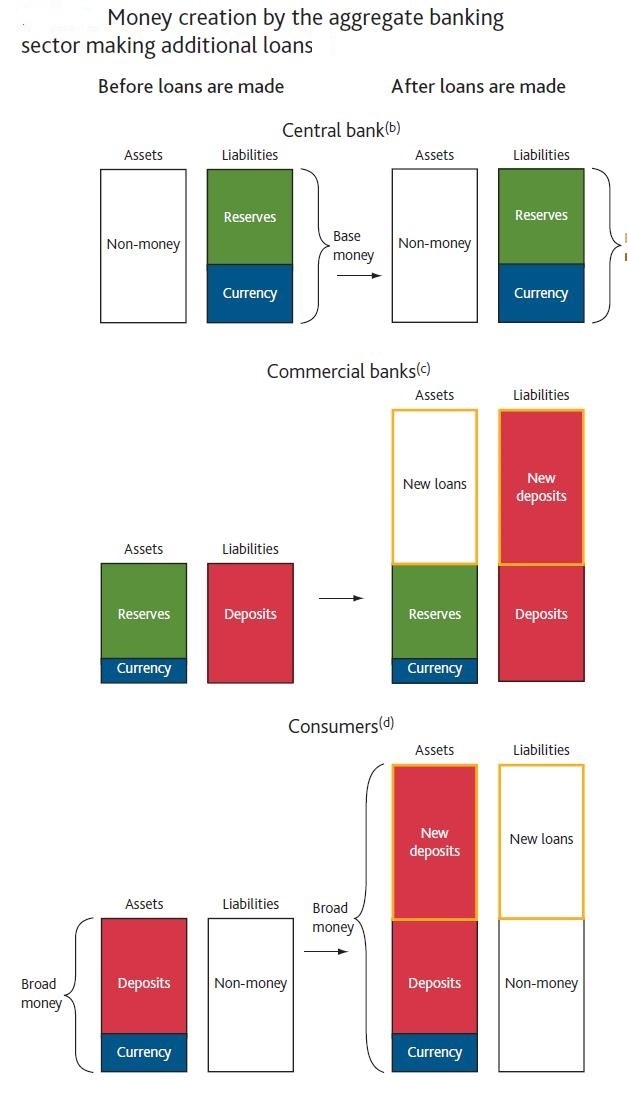

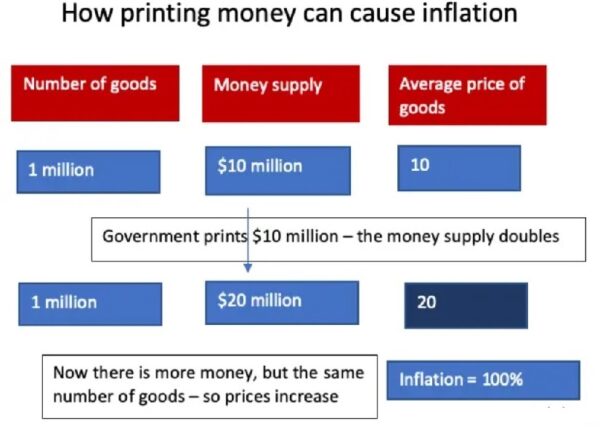

Technological progress has historically enabled the development of new forms of money with novel and enhanced properties. The introduction of coins and paper money, for instance, improved portability and cognizability relative to commodity money. Private bank money offered the possibility to earn interest and (eventually) transact digitally. Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, provided censorship resistance. Central bank digital currencies, which are under research and development at an increasing number of central banks, promise to restore public money, but in a digital form. And quantum money, which has been theoretically studied but is not yet technically feasible, could reproduce the properties of cash, but with improved unforgeability guarantees and the ability to transact digitally.