Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

POPULATION PROBLEM

Population Problem:

_

_

Prologue:

In an interview given to Economic Times, JRD Tata had reminisced how Nehru once retorted to his concerns on rising population. “Nonsense, a large population is the greatest source of power of any nation,” the first prime minister of Independent India is believed to have told the industry doyen. Subsequently India’s bulging population was seen as threat to the country’s future so much so that Nehru’s grandson, Sanjay Gandhi, ran a controversial campaign of forced sterilization during the emergency (1975-77). Their present Prime Minister Narendra Modi red-flagged population explosion in the course of his Independence Day speech.

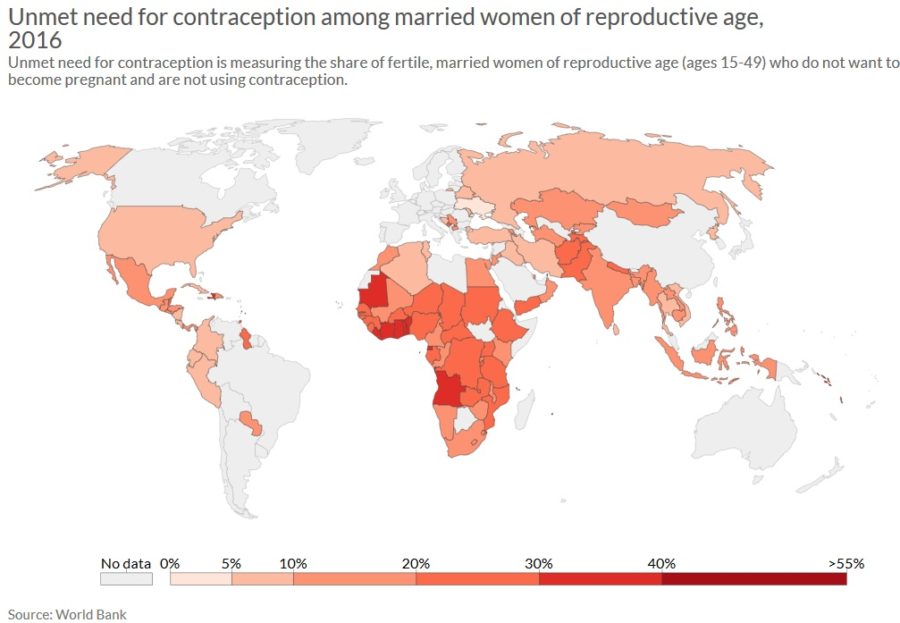

Mainstream politicians, journalists, and academics frequently avoid discussing population issues since notions about population are often seen as being politically or ideologically motivated. As a result, population debates are generally argued from the fringes. Some groups characterize population growth as a Ponzi scheme, whereby increasing numbers of youth are constantly required to support older generations. Antiimmigration activists mobilize overpopulation fears in an attempt to justify legislative actions against immigration. Environmental organizations generally cite population growth as an unsustainable stress on natural ecosystems and resources. There are reasons to worry about the long-term effects of population growth on the environment and quality of life. Humane and non-coercive strategies are available to stabilize our population without draconian population laws. These measures use education (especially of young women), family planning and access to contraception, and they focus on allowing women to make their own choice about how many children they have.

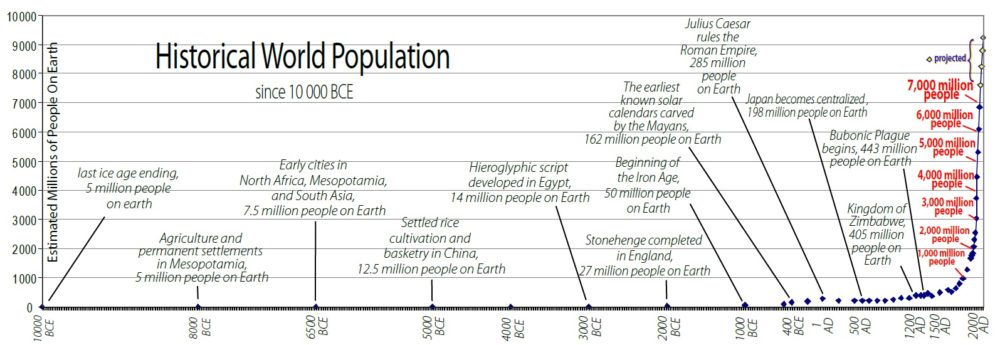

It took hundreds of thousands of years for humans to hit the 1 billion mark in 1800. We added the next billion by 1928. In 1960, we hit 3 billion. In 1975, 4 billion. That sounds like the route to an overpopulation apocalypse. Ever since Thomas Malthus published “An Essay on the Principle of Population” in 1798, speculating that humans’ proclivity for procreation would exhaust the global food supply within a matter of decades, population growth has been a hot issue among those contemplating humankind’s future. However, since Malthus first published his famous Essay on Population in 1798, the world population has grown nearly six times larger, while food output and consumption per person are considerably higher now, and there has been an unprecedented increase both in life expectancies and in general living standards. The fact that Malthus was mistaken in his diagnosis as well as his prognosis two hundred years ago does not, however, indicate that contemporary fears about population growth must be similarly erroneous.

Few issues today are as divisive as what is called the “world population problem.” Divisions among experts are receiving enormous attention and generating considerable heat. There is a danger that in the confrontation between apocalyptic pessimism on the one hand and a dismissive smugness on the other, a genuine understanding of the nature of the population problem may be lost. Visions of impending doom have been increasingly aired in recent years, often presenting the population problem as a ‘bomb’ that has been planted and is about to ‘go off.’ If the propensity to foresee impending disaster from overpopulation is strong in some circles, so is the tendency in others to dismiss all worries about population size. Critics argue that action to address population creates social and economic segregation, and portray overpopulation concerns as being “anti-poor,” “anti-developing country,” or even “anti-human.” Some say the real problem facing humanity is aging and declining world population.

While the Northern populations are declining (and consumption still rising), the Southern countries, particularly in sub Saharan Africa, are still growing in population. The ethical question posed is that the global “North” or “West” should not tell people in the “South” that they should have fewer children, opening a Pandora’s box of potential accusations. In this critique, those who link population to sustainability are branded neo-Malthusian, racist, or misanthropic.

I have discussed “overpopulation” very briefly on January 23, 2010 on this website. Now it is time to discuss “Population Problem” in detail.

______

Abbreviations and synonyms:

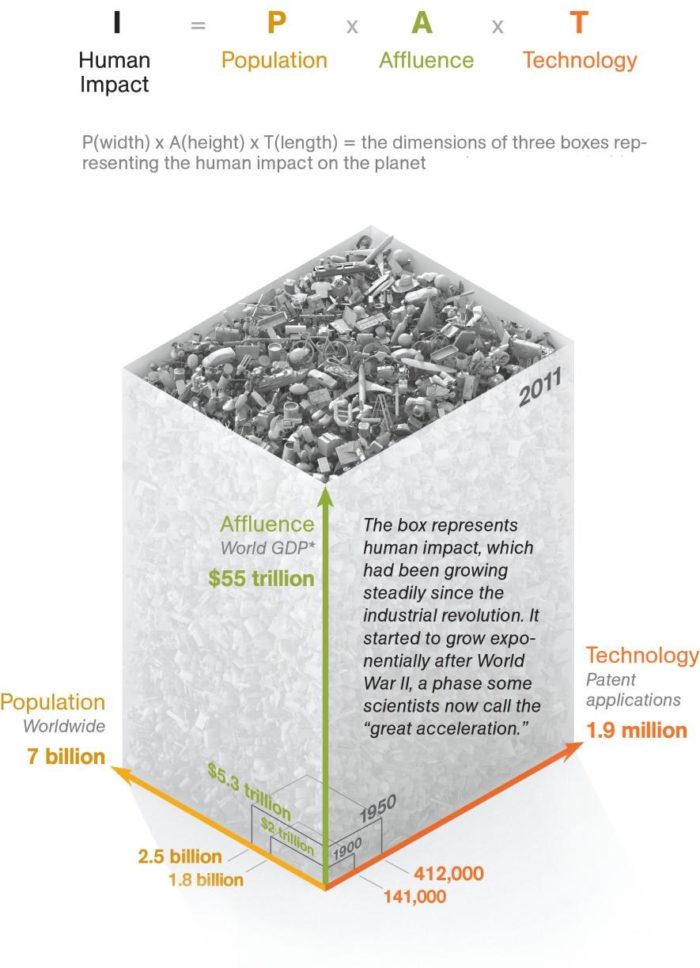

IPAT means Impact = Population X Affluence X Technology

UNFPA = UN Population Fund = United Nations Fund for Population Activities

LEDC = Less Economically Developed Country = Less Developed Country (LDC)

MEDC = More Economically Developed Country = More Developed Country (MDC)

TFR = Total Fertility Rate

HRD = Human Resource Development

FAO = Food and Agriculture Organization of UN

MEA = Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

PGR = Population Growth Rate

CBR = Crude Birth Rate

RNI = Rate of Natural Increase (of population)

_____

Some Quotes on Population:

The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.

V.S. Naipaul, A Bend in the River

_

A crowded society is a restrictive society; an overcrowded society becomes an authoritarian, repressive and murderous society.

Edward Abbey

_

Ozone depletion, lack of water, and pollution are not the disease-they are the symptoms. The disease is overpopulation. And unless we face world population head-on, we are doing nothing more than sticking a Band-Aid on a fast-growing cancerous tumor.

Dan Brown, Inferno

_

Short of nuclear war itself, population growth is the gravest issue the world faces. If we do not act, the problem will be solved by famine, riots, insurrection and war.

Robert McNamara, Former World Bank President

_

Pressures resulting from unrestrained population growth put demands on the natural world that can overwhelm any efforts to achieve a sustainable future. If we are to halt the destruction of our environment, we must accept limits to that growth.

World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity, signed by 1600 senior scientists from 70 countries, including 102 Nobel Prize laureates

_

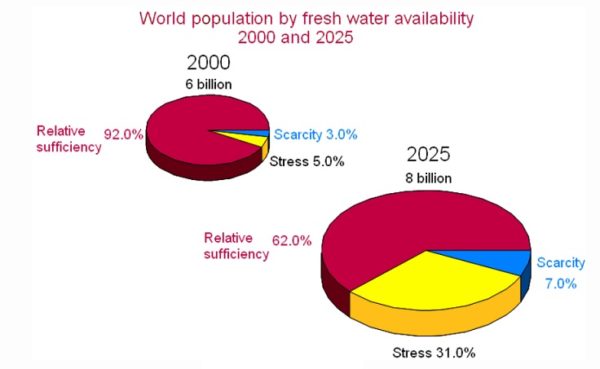

The colonization-followed-by-extinction pattern can be seen as recently as 2,000 years ago, when humans colonized Madagascar and quickly drove elephants, birds, hippos, and large lemurs extinct. The first wave of extinctions targeted large vertebrates hunted by hunter-gatherers. The second, larger wave began 10,000 years ago as the discovery of agriculture caused a population boom and a need to plow wildlife habitats, divert streams, and maintain large herds of domestic cattle. The third and largest wave began in 1800 with the harnessing of fossil fuels. With enormous, cheap energy at its disposal, the human population grew rapidly from 1 billion in 1800 to 2 billion in 1930, 4 billion in 1975, and over 7 billion today. If the current course is not altered, we’ll reach 8 billion by 2020 and 9 to 15 billion (likely the former) by 2050.

Center for Biological Diversity

________

Some facts about Population:

- The world population reached 7.7 billion in 2019. The world has added around one billion people over the last twelve years.

- With the world’s population growing by 1.08 percent per year (83 million people annually), it is estimated that the global population will 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100.

- 50.4 percent of the world’s population is male and 49.6 percent is female.

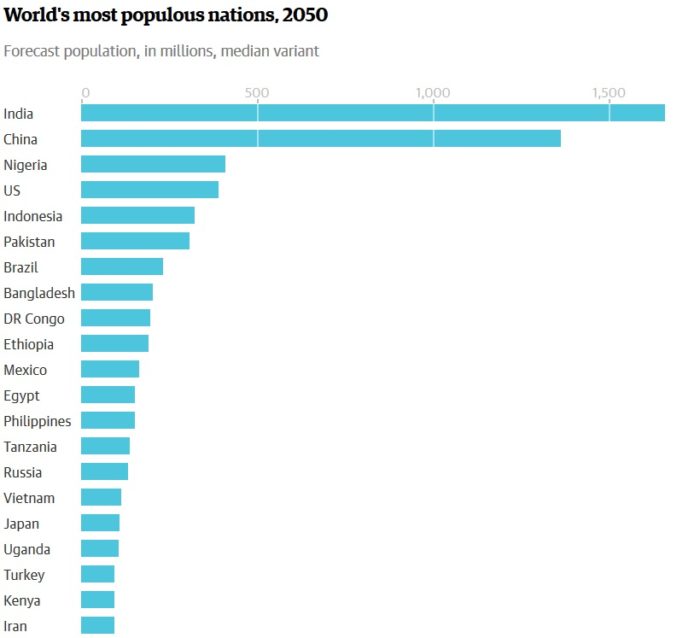

- Statistics show that half of the world’s population growth will be concentrated in just nine countries: India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Ethiopia, the United Republic of Tanzania, the United States of America, Uganda and Indonesia (in order of their contribution to world population).

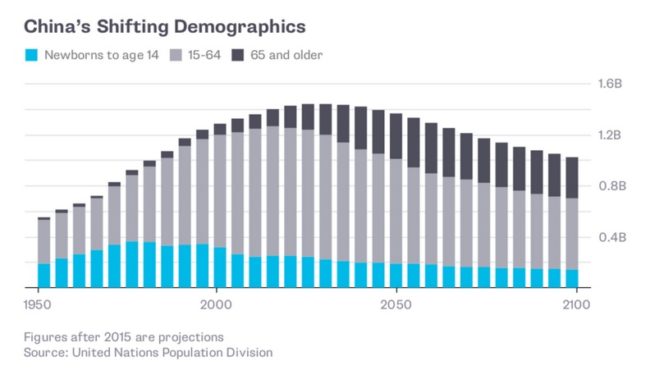

- China (1.41 billion) and India (1.34 billion) continue to be the two most crowded countries of the world, representing 19 and 18 percent of the world’s population, respectively. In 2024, both countries are expected to have roughly 1.44 billion people. Thereafter, India’s population is projected to continue growing for several decades to around 1.5 billion in 2030 and approaching 1.66 billion in 2050, while the population of China is expected to remain stable until the 2030s, after which it may begin a slow decline.

- According to UNICEF (2009), 47 per cent of India’s women and 56 per cent of rural women aged 20–24 are married before the legal age of 18. It is shocking to note that 40 per cent of the world’s child marriages occur in India.

- India’s wheat and rice yields are 2.6 tons and 2.9 tons per hectare respectively as compared to 8 tons and 10 tons being the highest in the world. China produces 40 per cent more food than India on just 60 per cent of the arable land area of India.

______

______

Introduction to population problem:

The wish of the great majority of mankind to have children has extended across centuries, cultures, and classes. The survival of the human race demonstrates that most people have been willing to bear the cost of rearing two or more children to the age of puberty. Widely held ideas and common attitudes reflect and recognize the benefits parents expect from having children.

_

What is population?

Population is a summation of all the organisms of the same group or species, which live in a particular geographical area & have the capacity of interbreeding.

What does population mean?

-Total number of people inhabiting a specified area or territory (e.g. population of a village, city, state, country, world).

-Total number of people of a particular group, race, class or category (e.g. population of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, or religious groups like Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs)

-In biology, collection of inter-breeding organisms of a particular species (e.g. population of tigers, deer, etc.)

-In statistics, a population is the entire pool from which a statistical sample is drawn. A population may refer to an entire group of people, objects, events, hospital visits, or measurements. A population can thus be said to be an aggregate observation of subjects grouped together by a common feature.

_

Population growth has been propelled by a number of factors, including developments in medicine since the nineteenth century (e.g. the discovery of antibiotics); relative peace since the Second World War; and more efficient food production propelled by the Green Revolution. Antibiotics have helped to rid humanity in most parts of the world from deadly pandemics such as cholera, plague, and tuberculosis. Today, while infectious diseases such as HIV, Ebola virus, and malaria are not yet overcome, survival chances of individuals suffering these diseases have increased. Noninfectious wealthy world diseases such as cancer and diabetes may be on the rise, yet due to better medical care, they do not necessarily condemn the patients to death. Better health, peace, and abundant food are all economic development benefits certainly something that we all celebrate.

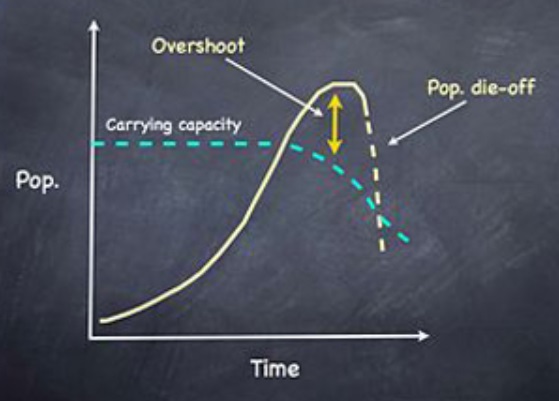

In the twentieth century, medical and resource constraints have become easier to manage with the Green Revolution which has enabled humans to produce much more food than Malthus could have imagined. In more contemporary writing, Childe (1951) saw population growth as dependent on subsistence, perceiving foragers as severely restricted by a low carrying capacity. The adoption of farming raised the carrying capacity and so made possible a “population explosion” (Netting 1977, p. 13). The economist Ester Boserup (1965) has emphasized that population growth causes a higher carrying capacity by forcing people to use land more intensively and to adopt technological innovations that make more intensive land use possible.

Yet, the negative side of population growth has also been noted. Thomas Malthus’ (1798) An Essay on the Principle of Population, is one of the best-known and most criticized classical texts on population. Malthus postulated that there are certain “checks” on population expansion, emerging “from the difficulty of subsistence,” including struggle for resources, diseases, and starvation. As land and resources are not unlimited, checks of growth must be in place to avoid Malthusian “controls.” The publication of The Population Bomb (Ehrlich 1968; for an update see Ehrlich & Ehrlich 2009) and The Limits of Growth (published in 1972, for an update see Meadows et al. 2004), linked some Malthusian ideas to the twentieth-century sustainability issues. The Population Bomb offered a model warning that technology may not be sufficient to curtail the devastating effects of increasing populations. Although they were labeled “extremists” and alarmists at the time (Ehrlich and Ehrlich (2014), today we see that their predictions for environmental damage due to excessive population growth, technological and industrial “innovations” to be right on the pulse of global concerns.

Expanding population can become a threat to humanity itself, as it undermines its own resource base, ultimately leading to the reassertion of “natural” controls. A well-known anthropologist Gregory Bateson (1972) noted how when faced with challenges of altered natural conditions, we tend to focus on modifying our environment rather than ourselves. Bateson argued that these basic causes of environmental crisis lie in the combined action of (a) technological advance, (b) population increase, and (c) conventional (but wrong) ideas about the “nature of man” and his relation to the environment. While technological advance has created unintended but extremely destructive effects on the environment, population increase has exacerbated the challenges. The present way of thinking about the primacy of economic agendas has made the challenge of demographic sustainability even more urgent. As Ehrlich and Ehrlich (2014) have long pointed out, the environmental impact is population times consumption, and we cannot ignore either.

_

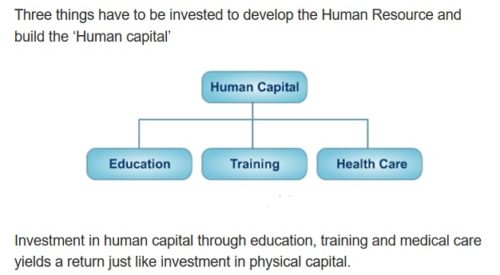

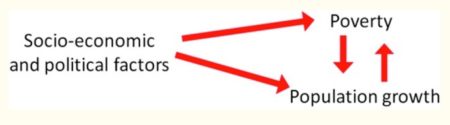

Social Scientists and demographers have for long debated the relation among population, environment and development. In recent times, the old debate has yet again become popular due to new but opposite evidences like expansion of labour market owing to economic globalisation on the one hand and ecological crisis because of global warming on the other. Though the problem of “over‟ or “under‟ population hunts many countries of the world today, the societies of the third world are particularly faced with the problem of “population bomb‟ (Ehrlich 1968). In order to attain the cherished goal of sustainable development, these societies need to improve the quality of life and material security of the billion poorest people as well as to realize an ecological wisdom of intergenerational equity in the use of natural resources (Mehta 1997). Although human resource is a significant factor in development, any sustainable society also requires an optimum population to realise the goals of equity and efficiency. As our earth has a carrying capacity, it cannot sustain any unlimited number of people for maximum period of time. There is no doubt about the fact that any additional number of human populations puts demands for more houses, schools, hospitals, roads, jobs etc., and when a society fails to meet these increasing demands, the socio-cultural, economic and political environment degrades. Contrarily, the “success‟ of a society to meet the additional demands of its population puts constraint on environment. The overpopulation question has therefore occupied a pivotal place in any discourse on development in the countries like India. But, in recent years, globalization has, at least theoretically, enhanced the possibility of labour migration, mobility and involvement of “excess‟ (in the form of unemployed or under-employed persons) labour in the expanding areas of our economic activities. It is argued that our population itself is our strength as huge population offers a bigger pool of human resource and hence a bigger consumer market too (Roche 2012). The trend towards shifting of manufacturing and information technology-based industries from the advance industrialised countries to those where labour is cheap appears to be our “advantage‟ now. Looking into this aspect of utilisation of “human resource‟ and the existence of huge “youth power‟ in the country, some have argued that India’s over-population is a prerequisite to development and not a liability in the changed context. Yet, as noted by the Asian Development Bank, “The demographic dividend is not, however, an automatic consequence of demographic changes. Rather, it depends on the ability of the economy to productively use its additional workers‟ (ADB 2011).

_

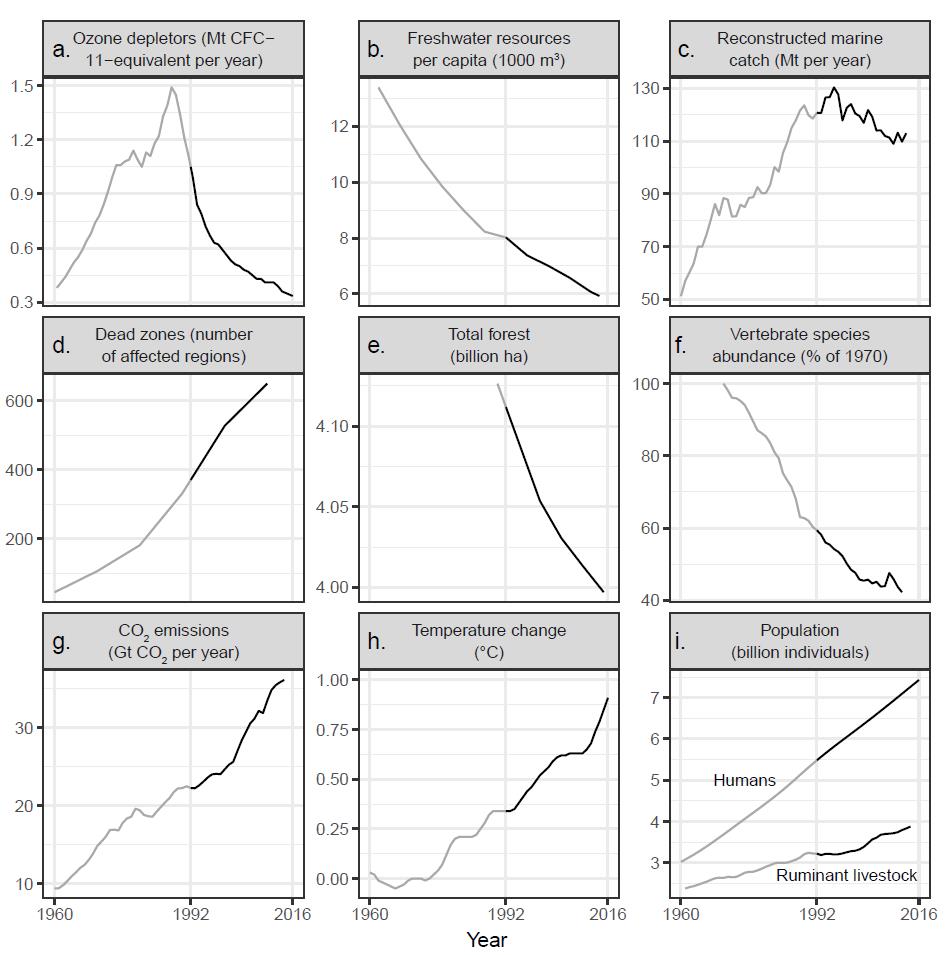

Some people say that the world is not overpopulated and that the main issue is overconsumption. It’s pointless talking about overpopulation without considering the consumption patterns. Look up ecological overshoot. It occurs when a population temporarily exceeds the long-term carrying capacity of its environment. We use more ecological resources and services than nature can regenerate through overfishing, overharvesting forests, and emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than forests can sequester. The earth is in the midst of the sixth mass extinction and we have lost more than 50% wildlife in the last 40 years. It’s true that some nations are more densely populated than others, however, the planet is overpopulated by humans. The world is also overpopulated with cows, pigs, chickens, and turkeys, but these animals are artificially being bred for human consumption. You could probably put all the 7.7 billion people into a state of the size of Texas, but they would still require land, water, and other resources for the goods they consume and we are running out of those resources. And while you may outsource manufacturing to continue enjoying cheap goods, the warming is global. In some nations, the air quality is so poor, they even sell air pollution masks to prevent cancer and lung diseases. Overpopulation and overconsumption are two sides of the same coin. We have to work on reducing both. 7.7 billion people aspiring to live a western lifestyle is a recipe for disaster!

_

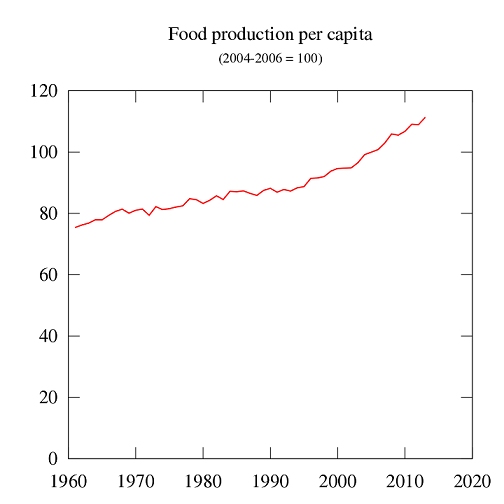

In a famous 1798 essay, Thomas Malthus proposed that human population would grow more rapidly than our ability to grow food, and that eventually we would starve. He asserted that the population would grow geometrically—1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32—and that food production would increase only arithmetically—1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. So food production would not keep up with our expanding appetites. As more people entered the workforce, wages would fall and goods would become scarce. Calamity was inevitable. He observed that although an increase in food production of a nation led to population growth, the improvement was temporary. Rapid population growth normalised and restored the original per capita consumption level. Malthus asserted that there was the tendency of humans for greater consumption of food and other resources rather than improvement of quality and standard of living. It was dubbed as the “Malthusian trap.” When population reached certain level of growth, the poor people experience economic hardships, making them more vulnerable to famine and disease. Malthus’s rationale was so influential that this mode of thinking was soon called ‘Malthusian.’ Even though more than 800 million people worldwide don’t have enough to eat now, the mass starvation Malthus envisioned hasn’t happened. This is primarily because advances in agriculture—including improved plant breeding and the use of chemical fertilizers—have kept global harvests increasing fast enough to mostly keep up with demand. Still, researchers such as Jeffrey Sachs and Paul Ehrlich continue to worry that Malthus eventually might be right. Ehrlich, a Stanford University population biologist, wrote a 1968 bestseller called The Population Bomb, which warned of mass starvation in the 1970s and 1980s because of overpopulation. Even though he drastically missed that forecast, he continues to argue that humanity is heading for calamity. Ehrlich says the key issue now is not just the number of people on Earth, but a dramatic rise in our recent consumption of natural resources, which Elizabeth Kolbert explored in 2011 in an article called “The Anthropocene—The Age of Man.” As part of this human-dominated era, the past half century also has been referred to as a period of “Great Acceleration” by Will Steffen at International Geosphere-Biosphere Program. Besides a nearly tripling of human population since the end of World War II, our presence has been marked by a dramatic increase in human activity—the damming of rivers, soaring water use, expansion of cropland, increased use of irrigation and fertilizers, a loss of forests, and more motor vehicles. There also has been a sharp rise in the use of coal, oil, and gas, and a rapid increase in the atmosphere of methane and carbon dioxide, greenhouse gases that result from changes in land use and the burning of such fuels.

_

Measuring our rising Impact:

As a result of this massive expansion of our presence on Earth, scientists Ehrlich, John Holdren, and Barry Commoner in the early 1970s devised a formula to measure our rising impact, called IPAT, in which (I)mpact equals (P)opulation multiplied by (A)ffluence multiplied by (T)echnology.

The IPAT formula, they said, can help us realize that our cumulative impact on the planet is not just in population numbers, but also in the increasing amount of natural resources each person uses. The graphic above, which visualizes IPAT, shows that the rise in our cumulative impact since 1950—rising population combined with our expanding demand for resources—has been profound.

IPAT is a useful reminder that population, consumption, and technology all help shape our environmental impact, but it shouldn’t be taken too literally. University of California ecologist John Harte has said that IPAT “. . . conveys the notion that population is a linear multiplier. . . . In reality, population plays a much more dynamic and complex role in shaping environmental quality.”

One of our biggest impacts is agriculture. Whether we can grow enough food sustainably for an expanding world population also presents an urgent challenge, and this becomes only more so in light of these new population projections. Where will food for an additional 2 to 3 billion people come from when we are already barely keeping up with 7 billion? Such questions underpin a 2014 National Geographic series on the future of food. As climate change damages crop yields and extreme weather disrupts harvests, growing enough food for our expanding population has become what The 2014 World Food Prize Symposium calls “the greatest challenge in human history.”

_

There are more than 7 billion people on Earth now, and roughly one in eight of us doesn’t have enough to eat. The question of how many people the Earth can support is a long-standing one that becomes more intense as the world’s population—and our use of natural resources—keeps booming. Recently two conflicting projections of the world’s future population were released. A new United Nations and University of Washington study in the journal Science says it’s highly likely we’ll see 9.6 billion Earthlings by 2050, and up to 11 billion or more by 2100. These researchers used a new “probabilistic” statistical method that establishes a specific range of uncertainty around their results. Another study in the journal Global Environmental Change projects that the global population will peak at 9.4 billion later this century and fall below 9 billion by 2100, based on a survey of population experts. Who is right? After all, how many of us there are, how many children we have, how long we live, and where and how we live affect virtually every aspect of the planet upon which we rely to survive: the land, oceans, fisheries, forests, wildlife, grasslands, rivers and lakes, groundwater, air quality, atmosphere, weather, and climate.

_

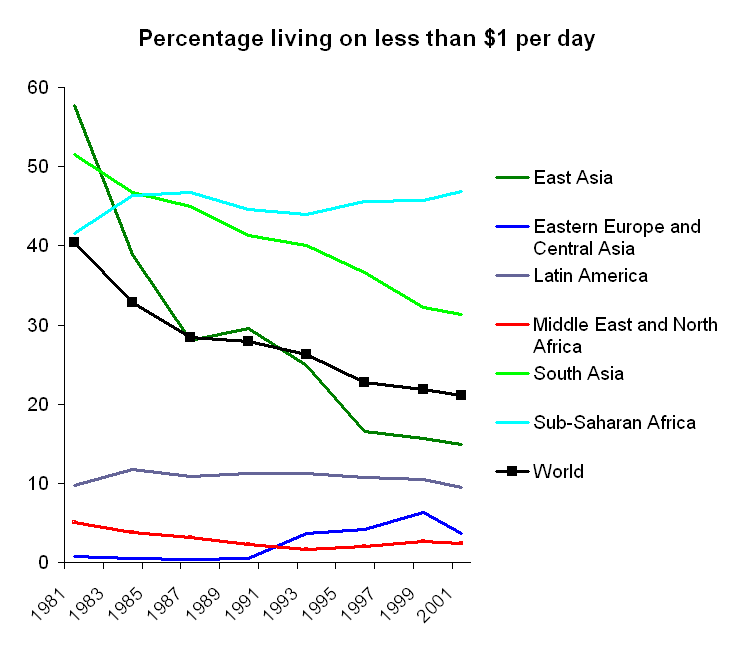

Significant progress has been made over the past 20 years in combating global poverty and addressing other internationally agreed development goals, such as improving gender equality, lowering child mortality, raising educational attainment and improving sanitation and access to clean drinking water. However, progress has been uneven within and across countries and regions and the benefits of social and economic progress have not been shared equally. At the same time, there is growing evidence that population growth, combined with economic development, rising standards of living and a higher level of consumption has resulted in changing patterns of land use, increased energy use and the depletion of natural resources, with signs of climate change and environmental degradation more visible than ever before.

______

Population’s Structure: Fertility, Mortality and Migration:

Population is not just about numbers of people. Demographers typically focus on three dimensions—fertility, mortality, and migration—when examining population trends. Fertility examines how many children a woman bears in her lifetime, mortality looks at how long we live, and migration focuses on where we live and move. Each of these population qualities influences the nature of our presence and impact across the planet.

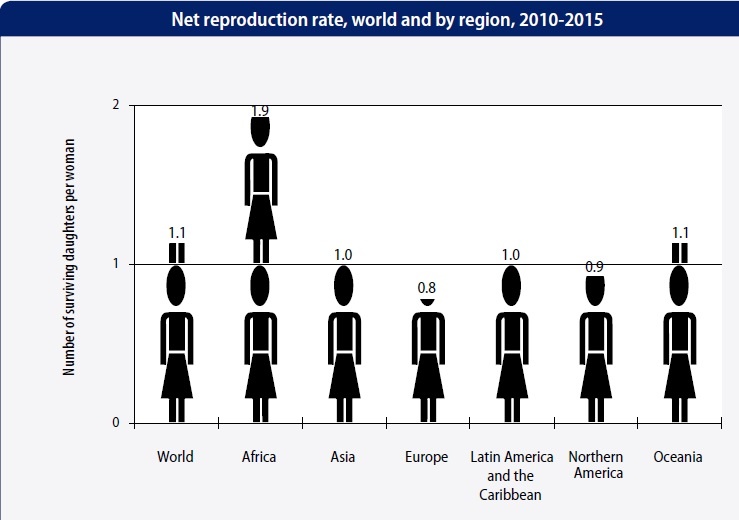

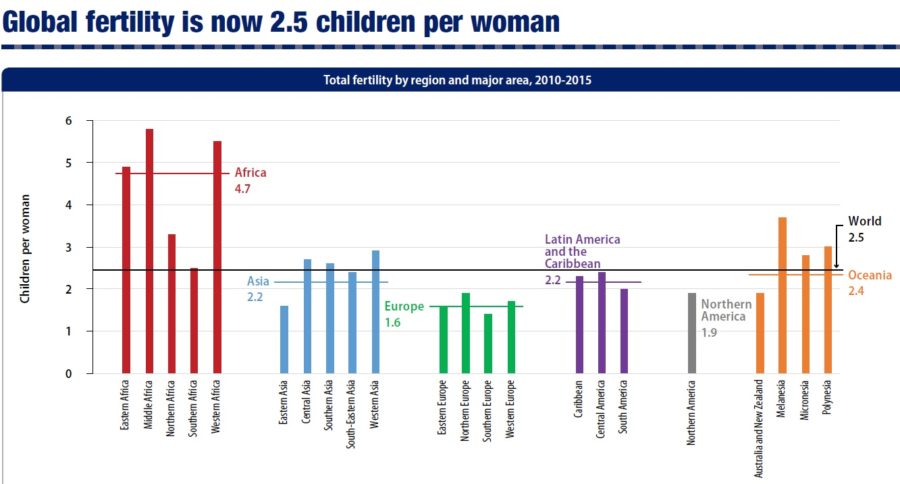

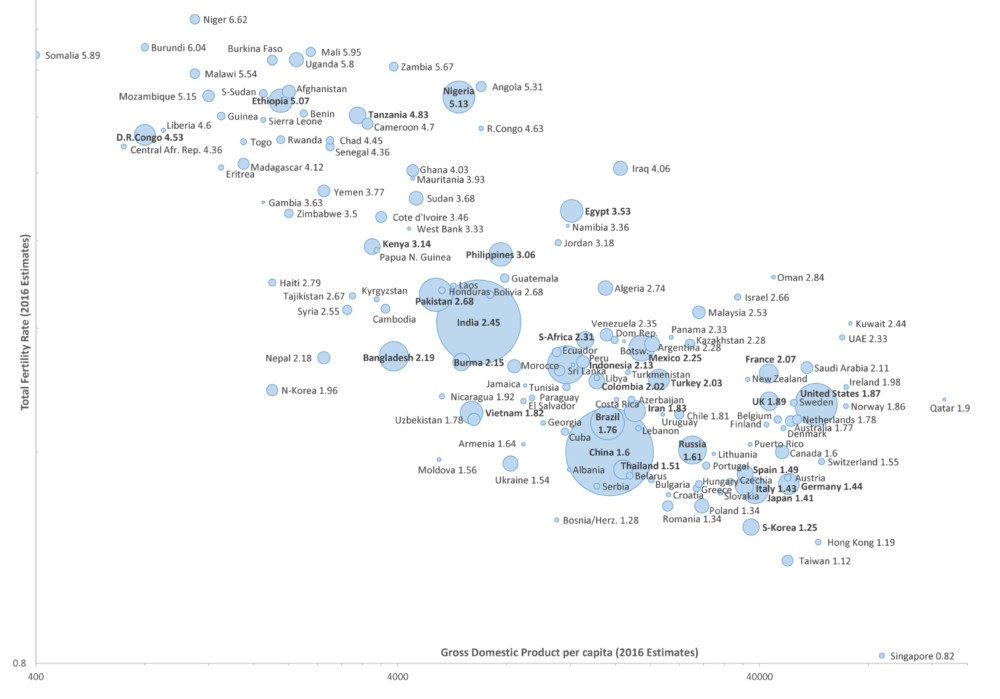

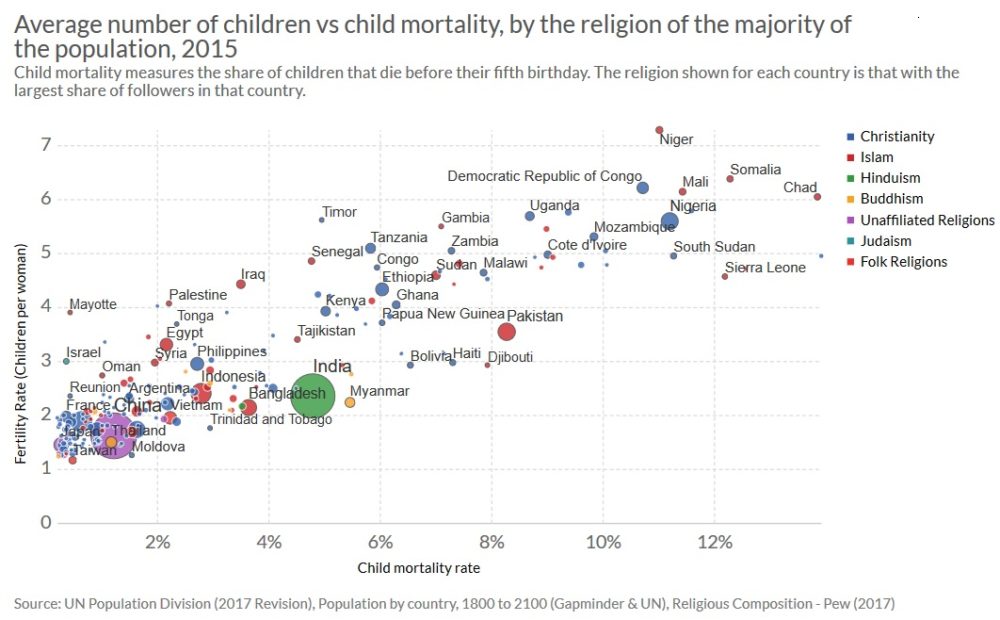

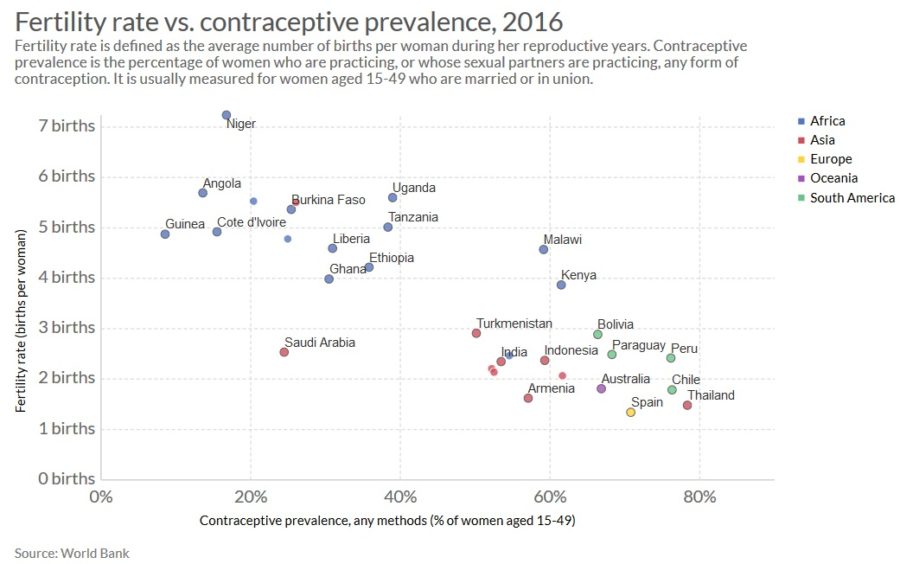

The newly reported higher world population projections result from continuing high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. The median number of children per woman in the region remains at 4.6, well above both the global mean of 2.5 and the replacement level of 2.1. Since 1970, a global decline in fertility—from about 5 children per woman to about 2.5—has occurred across most of the world: Fewer babies have been born, family size has shrunk, and population growth has slowed. In the United States, fertility is now slightly below replacement level. Reducing fertility is essential if future population growth is to be reined in. Cynthia Gorney wrote about the dramatic story of declining Brazilian fertility as part of National Geographic’s 7 Billion series. Average family size dropped from 6.3 children to 1.9 children per woman over two generations in Brazil, the result of improving education for girls, more career opportunities, and the increased availability of contraception. Mortality—or birth rates versus death rates—and migration (where we live and move) also affect the structure of population. Living longer can cause a region’s population to increase even if birth rates remain constant. Youthful nations in the Middle East and Africa, where there are more young people than old, struggle to provide sufficient land, food, water, housing, education, and employment for young people. Besides the search for a life with more opportunity elsewhere, migration also is driven by the need to escape political disruption or declining environmental conditions such as chronic drought and food shortages.

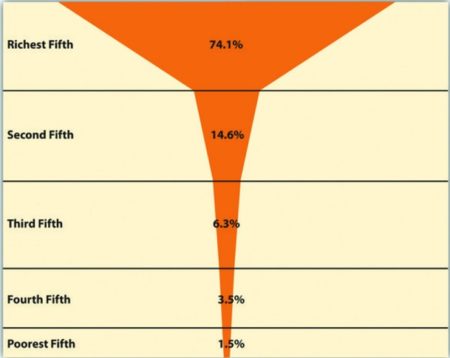

A paradox of lower fertility and reduced population growth rates is that as education and affluence improves, consumption of natural resources increases per person. In other words, (as illustrated in the IPAT graphic above) as we get richer, each of us consumes more natural resources and energy, typically carbon-based fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. This can be seen in consumption patterns that include higher protein foods such as meat and dairy, more consumer goods, bigger houses, more vehicles, and more air travel.

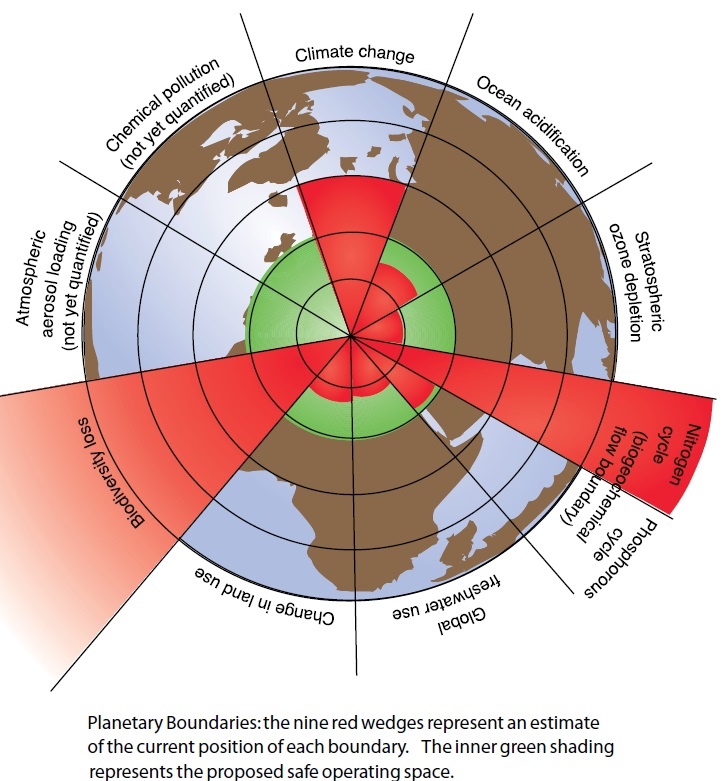

When it comes to natural resources, studies indicate we are living beyond our means. An ongoing Global Footprint Network study says we now use the equivalent of 1.7 planets to provide the resources we use, and to absorb our waste. A study by the Stockholm Resilience Institute has identified a set of “nine planetary boundaries” for conditions in which we could live and thrive for generations, but it shows that we already have exceeded the institute’s boundaries for climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, altered biogeochemical cycles (phosphorus and nitrogen).

Those of you reading my article are among an elite crowd of Earthlings. You have reliable electricity, access to Internet-connected computers and phones, and time available to contemplate these issues. About one-fifth of people on Earth still don’t have access to reliable electricity. So as we debate population, things we take for granted—reliable lighting and cooking facilities, for example—remain beyond the reach of about 1.3 billion or more people. Lifting people from the darkness of energy poverty could help improve lives. As World Bank Vice President Rachel Kyte says, “It is energy that lights the lamp that lets you do your homework, that keeps the heat on in a hospital, that lights the small businesses where most people work. Without energy, there is no economic growth, there is no dynamism, and there is no opportunity.” Improved education, especially for girls, is cited as a key driver of declining family size. Having light at night can become a gateway to better education for millions of young people. So when we debate population, it’s important to also discuss the impact—the how we live—of the population equation. While new projections of even higher world population in the decades ahead are cause for concern, we should be equally concerned about—and be willing to address—the increasing effects of resource consumption and its waste.

_______

Numerous population and environmental theorists characterize human population growth as an unsustainable pandemic accountable for a variety of ecological problems. However, regional consumption patterns amplify the environmental impact of a population, making the two factors (consumption and population) difficult to evaluate separately. For instance, a billion subsistence farmers may instigate less environmental impact than a much smaller quantity of rich consumers. The United States Census Bureau expects the world population will peak at about 9 billion by 2043. Such a large number of humans might not cause a problem if everyone were simple subsistence farmers. But clearly this is not the case. Most rich-world inhabitants each consume much more than a subsistence farmer in terms of products, services, and energy. These lofty consumption practices intensify a population’s impact on the biosphere. Furthermore, controversy surrounds calls for population reduction. Many environmentalists advocate for wider distribution of family planning services, contraception, and sexual education to prevent population growth. Meanwhile, some rights advocates insist that population growth is the symptom of larger cultural injustices and that contraceptives are inappropriate tools to address these underlying inequities. Environmental theorists debate the impact of population and consumption on the global ecosystem. Cornucopian theorists believe that technological innovation will allow for continuing growth despite a growing population with high levels of consumption.

_____

Neo-Malthusianism:

Neo-Malthusianism is the advocacy of population control programs to ensure resources for current and future populations. Malthus and the later thinkers alarmed by rapid population growth, including Paul Ehrlich, focused primarily on the effects of overpopulation on the human species in relation to the “carrying capacity” of the earth: that loss of human habitat and resources that would result in human die-backs if population growth could not be controlled. More recently, theorists of the Anthropocene have become concerned with the impact on earth systems themselves, in addition to the impact on humans, of continuing growth in the human population—this is, after all, what is seen as the cause of the damage to earth systems. Humans are spoiling their nest, to put the neo-Malthusian concern in other words, and it may not be possible to repair the damage even if their growth in numbers is curtailed. This fuels the neo-Malthusian view. There is only one morally acceptable option: effective population control. To consign living people to catastrophic die-back is not a morally satisfactory solution; and there is no third alternative. Nature in this sense is harsh: control your growth or suffer disastrous consequences.

______

______

How many children can you have in a lifetime?

There is a limit to how many children one person can have, but that number is much higher for men than it is for women. One study estimated a woman can have around 15-30 children in a lifetime, taking pregnancy and recovery time into account. Since men require less time and fewer resources to have kids, the most “prolific” fathers can have up to about 200 children. The number of children men can have depends on the health of their sperm and other factors like how many women they can reproduce with. In fact, studies suggest that men over 50 have up to a 38% lower chance of impregnating a woman compared to men under 30.

______

Why unrestrained population growth of humans is a bane.

Well, the human being is not just another animal but it is the only animal which

-can proliferate more than the capacity of the land to sustain it.

-can eat even when its hunger is assuaged.

-can consume more than it needs.

-can prolong life even after its time is past in a wish to live ‘forever’

-has no natural enemies in the normal course of things

-can neutralize or remove its natural enemies where and when they occur

-can work against Nature to do all the above.

‘Against Nature’ – is the operative word. Herein lies the bane.

The human is the only animal which can think, ruminate, plan, manipulate, discover and invent…in order to save, preserve and proliferate himself and his kind.

Almost every thought and act of Man since he appeared on Earth, has been to do the above.

Worse, he constantly interferes with Nature to do this.

______

______

History of population concern and population planning:

Ancient times through Middle Ages:

A number of ancient writers have reflected on the issue of population. At about 300 BC, the Indian political philosopher Chanakya (c. 350-283 BC) considered population a source of political, economic, and military strength. Though a given region can house too many or too few people, he considered the latter possibility to be the greater evil. Chanakya favored the remarriage of widows (which at the time was forbidden in India), opposed taxes encouraging emigration, and believed in restricting asceticism to the aged.

In ancient Greece, Plato (427-347 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC) discussed the best population size for Greek city-states such as Sparta, and concluded that cities should be small enough for efficient administration and direct citizen participation in public affairs, but at the same time needed to be large enough to defend themselves against hostile neighbors. In order to maintain a desired population size, the philosophers advised that procreation, and if necessary, immigration, should be encouraged if the population size was too small. Emigration to colonies would be encouraged should the population become too large. Aristotle concluded that a large increase in population would bring, “certain poverty on the citizenry and poverty is the cause of sedition and evil.” To halt rapid population increase, Aristotle advocated the use of abortion and the exposure of newborns (that is, infanticide).

Confucius (551-478 BC) and other Chinese writers cautioned that, “excessive growth may reduce output per worker, repress levels of living for the masses and engender strife.” Confucius also observed that, “mortality increases when food supply is insufficient; that premature marriage makes for high infantile mortality rates, that war checks population growth.”

Ancient Rome, especially in the time of Augustus (63 BC-AD 14), needed manpower to acquire and administer the vast Roman Empire. A series of laws were instituted to encourage early marriage and frequent childbirth. Lex Julia (18 BC) and the Lex Papia Poppaea (AD 9) are two well-known examples of such laws, which among others, provided tax breaks and preferential treatment when applying for public office for those that complied with the laws. Severe limitations were imposed on those who did not. For example, the surviving spouse of a childless couple could only inherit one-tenth of the deceased fortune, while the rest was taken by the state. These laws encountered resistance from the population which led to the disregard of their provisions and to their eventual abolition.

Tertullian, an early Christian author (ca. AD 160-220), was one of the first to describe famine and war as factors that can prevent overpopulation. He wrote: “The strongest witness is the vast population of the earth to which we are a burden and she scarcely can provide for our needs; as our demands grow greater, our complaints against Nature’s inadequacy are heard by all. The scourges of pestilence, famine, wars, and earthquakes have come to be regarded as a blessing to overcrowded nations since they serve to prune away the luxuriant growth of the human race.”

Ibn Khaldun, a North African Arab polymath (1332–1406), considered population changes to be connected to economic development, linking high birth rates and low death rates to times of economic upswing, and low birth rates and high death rates to economic downswing. Khaldun concluded that high population density rather than high absolute population numbers was desirable to achieve more efficient division of labour and cheap administration.

During the Middle Ages in Christian Europe, population issues were rarely discussed in isolation. Attitudes were generally pro-natalist in line with the Biblical command, “Be ye fruitful and multiply.”

_

16th and 17th centuries:

European cities grew more rapidly than before, and throughout the 16th century and early 17th century discussions on the advantages and disadvantages of population growth were frequent. Niccolò Machiavelli, an Italian Renaissance political philosopher, wrote, “When every province of the world so teems with inhabitants that they can neither subsist where they are nor remove themselves elsewhere… the world will purge itself in one or another of these three ways,” listing floods, plague and famine. Martin Luther concluded, “God makes children. He is also going to feed them.”

Jean Bodin, a French jurist and political philosopher (1530–1596), argued that larger populations meant more production and more exports, increasing the wealth of a country. Giovanni Botero, an Italian priest and diplomat (1540–1617), emphasized that, “the greatness of a city rests on the multitude of its inhabitants and their power,” but pointed out that a population cannot increase beyond its food supply. If this limit was approached, late marriage, emigration, and the war would serve to restore the balance.

Richard Hakluyt, an English writer (1527–1616), observed that, “Through our long peace and seldom sickness… we are grown more populous than ever heretofore;… many thousands of idle persons are within this realm, which, having no way to be set on work, be either mutinous and seek alteration in the state, or at least very burdensome to the commonwealth.” Hakluyt believed that this led to crime and full jails and in A Discourse on Western Planting (1584), Hakluyt advocated for the emigration of the surplus population. With the onset of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), characterized by widespread devastation and deaths brought on by hunger and disease in Europe, concerns about depopulation returned.

_

Two centuries ago, Thomas Malthus’s Essay on Population warned that out-of-control population growth would deplete resources and bring about widespread famine. Malthus argued that, “Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence only increases in an arithmetical ratio.” He also outlined the idea of “positive checks” and “preventative checks.” “Positive checks”, such as diseases, wars, disasters, famines, and genocides are factors which Malthus believed could increase the death rate. “Preventative checks” were factors which Malthus believed could affect the birth rate such as moral restraint, abstinence and birth control. He predicted that “positive checks” on exponential population growth would ultimately save humanity from itself and he also believed that human misery was an “absolute necessary consequence.” Malthus went on to explain why he believed that this misery affected the poor in a disproportionate manner. After Malthus died, the Industrial Revolution brought about unprecedented prosperity that funded the construction of safe water supplies and sewage systems at a scale never before achieved. Living standards were transformed and lifespans lengthened. As farms mechanized, food became more plentiful even as the population grew. Famine became rarer. Throughout recorded history, population growth has usually been slow despite high birth rates, due to war, plagues and other diseases, and high infant mortality. During the 750 years before the Industrial Revolution, the world’s population increased very slowly, remaining under 250 million.

_

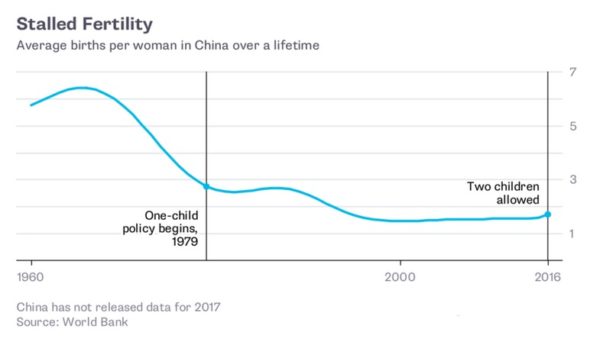

During the 19th century, Malthus’s work was often interpreted in a way that blamed the poor alone for their condition and helping them was said to worsen conditions in the long run. This resulted, for example, in the English poor laws of 1834 and in a hesitating response to the Irish Great Famine of 1845–52. By the 1970s, overpopulation hysteria came fully back into vogue. Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb in 1968, which opened with the lines, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Shortly thereafter, in 1972, the Club of Rome issued a report called The Limits to Growth. It bolstered the old argument that population growth would deplete resources and lead to a collapse of society with evidence from computer simulations based on dubious assumptions. Those jeremiads led to human rights abuses including millions of forced sterilizations in Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, Indonesia, Bangladesh and India, as well as China’s draconian one-child (now two-child) policy. In 1975, officials sterilized 8 million men and women in India alone. Were these human rights abuses necessary? No. Instead of facing widespread starvation and resource shortages, humanity managed to make resources more plentiful by using them more efficiently, increasing the supply and developing substitutes.

_

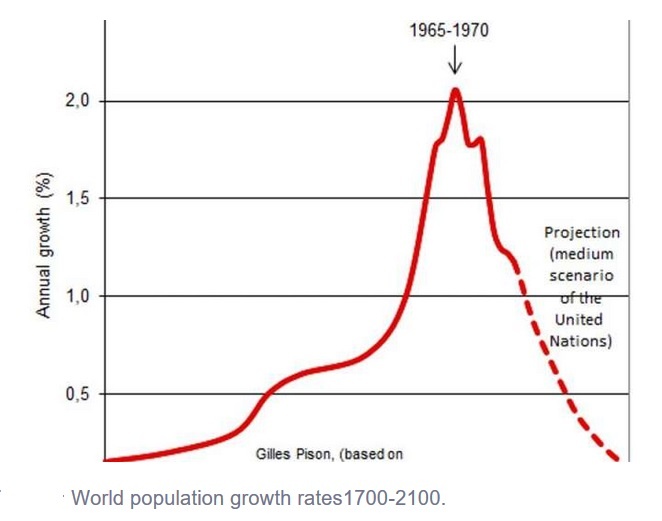

A 2014 study published in Science asserts that population growth will continue into the next century. Adrian Raftery, a University of Washington professor of statistics and sociology and one of the contributors to the study, says: “The consensus over the past 20 years or so was that world population, which is currently around 7 billion, would go up to 9 billion and level off or probably decline. We found there’s a 70 percent probability the world population will not stabilize this century. Population, which had sort of fallen off the world’s agenda, remains a very important issue.”

In 2017, more than a third of 50 Nobel prize-winning scientists surveyed by the Times Higher Education at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings said that human overpopulation and environmental degradation are the two greatest threats facing humankind. In November that same year, a statement by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries indicated that rapid human population growth is the “primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats.”

Even if overpopulation were to prove to be a problem, it is one with an expiration date: due to falling global birth rates, demographers estimate the world population will decrease in the long run. It is now well-documented that as countries grow richer, and people escape poverty, they opt for smaller families. It is almost unheard of for a country to maintain a high fertility rate after it passes about $5,000 in per-person annual income. The UN publication ‘World population prospects’ (2017) projects that the world population will reach 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100. Human population is predicted to stabilise soon thereafter.

______

______

World Population Growth:

Throughout most of history, the world’s population has been much smaller than it is now. Before the invention of agriculture, for example, the human population was estimated to be around 15 million people at most. The introduction of agriculture and the gradual movement of humanity into settled communities saw the global population increase gradually to around 300 million by AD 0. To give you an idea of scale, the Roman Empire, which many regards as one of the strongest empires the world has ever seen, probably contained only around 50 million people at its height; that’s less than the number of people in England today. It wasn’t until the early 19th century that the world population reached its first big milestone: 1 billion people. Then, as the industrial revolution took hold and living standards improved, the rate of population growth increased considerably. Over the next hundred years, the population of the world doubled, reaching 2 billion in the late 1920s. The 20th century, however, is where population growth really took off, and over the past 100 years, the planet’s population has more than tripled in size. This massive increase in human population is largely due to improvements in diet, sanitation and medicine, especially compulsory vaccination against many diseases. Today’s world population (~7.7 billion) is approximately 7% of the estimated 110 billion who have ever lived.

_

Here’s a timeline of the world population growth milestones:

- Year 1: 200 million

- Year 1000: 275 million

- Year 1500: 450 million

- Year 1650: 500 million

- Year 1750: 700 million

- Year 1804: 1 billion

- Year 1850: 1.2 billion

- Year 1900: 1.6 billion

- Year 1927: 2 billion

- Year 1950: 2.55 billion

- Year 1955: 2.8 billion

- Year 1960: 3 billion

- Year 1970: 3.7 billion

- Year 1985: 4.85 billion

- Year 1999: 6 billion

- Year 2011: 7 billion

- Year 2025: 8 billion

_

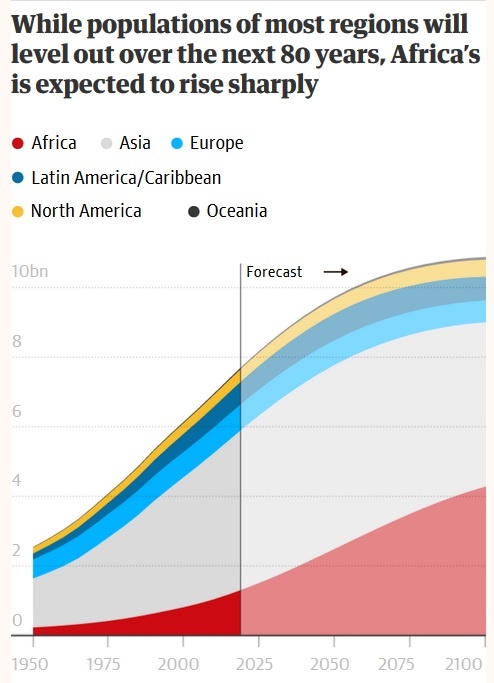

In 2014 the United Nations estimated there is an 80% likelihood that the world’s population will be between 9.6 billion and 12.3 billion by 2100. Most of the world’s expected population increase will be in Africa and southern Asia. Africa’s population is expected to rise from the current one billion to four billion by 2100, and Asia could add another billion in the same period. What happens next isn’t quite so clear. Most people agree that population increases will continue, but there are arguments about the rate of increase, and even a few people who believe population decreases are likely. The United Nations has gradually been revising its predictions downwards, and now believes that the world population in 2050 will be around 9 billion. It believes that, as the world grows steadily richer and the average family size decreases, growth will steadily slow and eventually stop. However, others believe that poverty will encourage steadily increasing growth, particularly in countries in Africa and parts of Asia, where growth is already much higher than the global average. A few scientists even believe that populations will decrease. Some believe that gradual increases in living standards will result in similar patterns to those in Western Europe, where birth rates are declining rapidly. Others believe that the current world population is unsustainable, and predict that humanity will simply not be able to produce enough food and oil to feed itself and sustain our industrial economy.

_____

United Nations role in population issues:

The United Nations system has long been involved in addressing these complex and interrelated issues – notably, through the work of the UN Population Fund (formerly United Nations Fund for Population Activities UNFPA) and the UN Population Division.

UN Population Division:

The Population Division pulls together information on such issues as international migration and development, urbanization, world population prospects and policies, and marriage and fertility statistics. It supports UN bodies such as the Commission on Population and Development, and supports implementation of the Program of Action adopted by the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (IPCD). The Population Division prepares the official United Nations demographic estimates and projections for all countries and areas of the world, helps States build capacity to formulate population policies, and enhances coordination of related UN system activities through its participation in the Committee for the Coordination of Statistical Activities.

UN Population Fund:

The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) started operations in 1969 to assume a leading role within the UN system in promoting population programs, based on the human right of individuals and couples to freely determine the size of their families. At the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 1994), its mandate was fleshed out in greater detail, to give more emphasis to the gender and human rights dimensions of population issues, and UNFPA was given the lead role in helping countries carry out the Conference’s Program of Action. The three key areas of the UNFPA mandate are reproductive health, gender equality, and population and development.

World Population Day is observed annually on 11 July. It marks the date, in 1987, when the world’s population hit the 5 billion mark.

_______

World Population by Country in 2019:

The current US Census Bureau world population estimate in June 2019 shows that the current global population is 7,577,130,400 people on earth, which far exceeds the world population of 7.2 billion from 2015. The estimate based on UN data shows the world’s population surpassing 7.7 billion.

China is the most populous country in the world with a population exceeding 1.4 billion. It is one of just two countries with a population of more than 1 billion, with India being the second. As of 2018, India has a population of over 1.355 billion people, and its population growth is expected to continue through at least 2050. By the year 2030, India is expected to become the most populous country in the world. This is because India’s population will grow, while China is projected to see a loss in population.

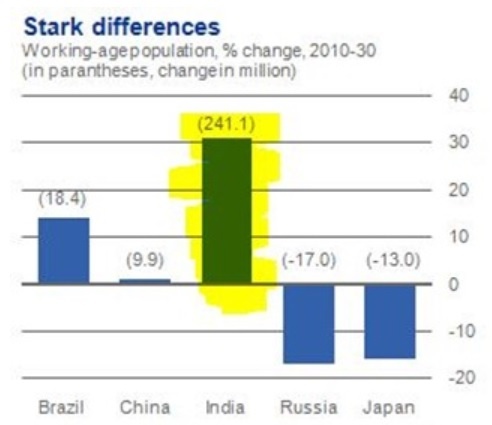

The next 11 countries that are the most populous in the world each have populations exceeding 100 million. These include the United States, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Russia, Mexico, Japan, Ethiopia, and the Philippines. Of these nations, all are expected to continue to grow except Russia and Japan, which will see their populations drop by 2030 before falling again significantly by 2050.

Many other nations have populations of at least one million, while there are also countries that have just thousands. The smallest population in the world can be found in Vatican City, where only 801 people reside.

In 2018, the world’s population growth rate was 1.10 %. Every five years since the 1970s, the population growth rate has continued to fall. The world’s population is expected to continue to grow larger but at a much slower pace. By 2030, the population will exceed 8 billion. In 2040, this number will grow to more than 9 billion. In 2055, the number will rise to over 10 billion, and another billion people won’t be added until near the end of the century. The current annual population growth estimates from the United Nations are in the millions – estimating that over 80 million new lives are added each year.

This population growth will be significantly impacted by nine specific countries which are situated to contribute to the population growth more quickly than other nations. These nations include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, and the United States of America. Particularly of interest, India is on track to overtake China’s position as the most populous country by the year 2030. Additionally, multiple nations within Africa are expected to double their populations before fertility rates begin to slow entirely.

Global life expectancy has also improved in recent years, increasing the overall population life expectancy at birth to just over 70 years of age. The projected global life expectancy is only expected to continue to improve – reaching nearly 77 years of age by the year 2050. Significant factors impacting the data on life expectancy include the projections of the ability to reduce AIDS/HIV impact, as well as reducing the rates of infectious and non-communicable diseases.

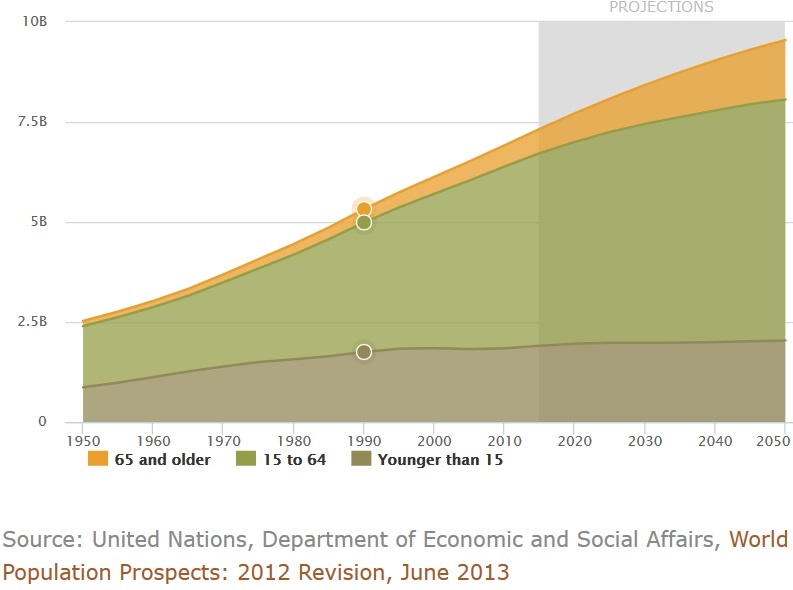

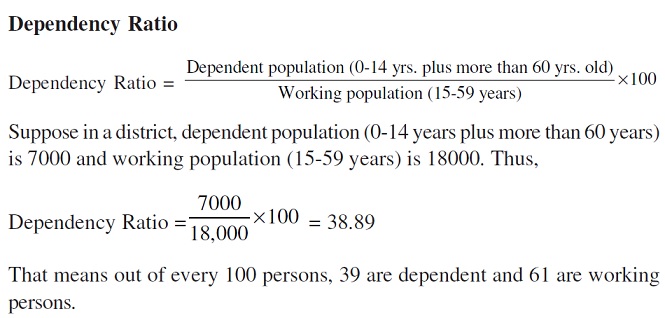

Population aging has a massive impact on the ability of the population to maintain what is called a support ratio. The support ratio is the number of people age 15–64 per one older person aged 65 or older. This ratio describes the burden placed on the working population by the non-working elderly population. As a population ages, the support ratio tends to fall. One key finding from 2017 is that the majority of the world is going to face considerable growth in the 60 plus age bracket. This will put enormous strain on the younger age groups as the elderly population is becoming so vast without the number of births to maintain a healthy support ratio.

____

Projections of population growth:

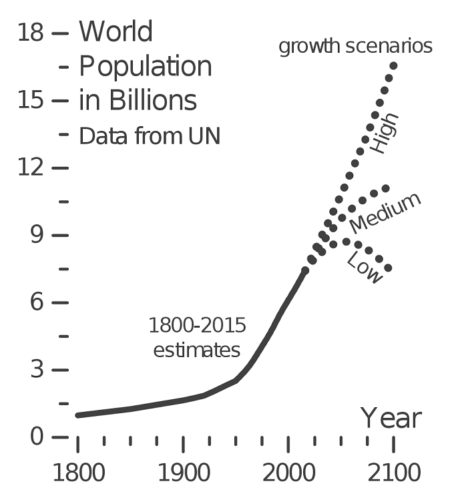

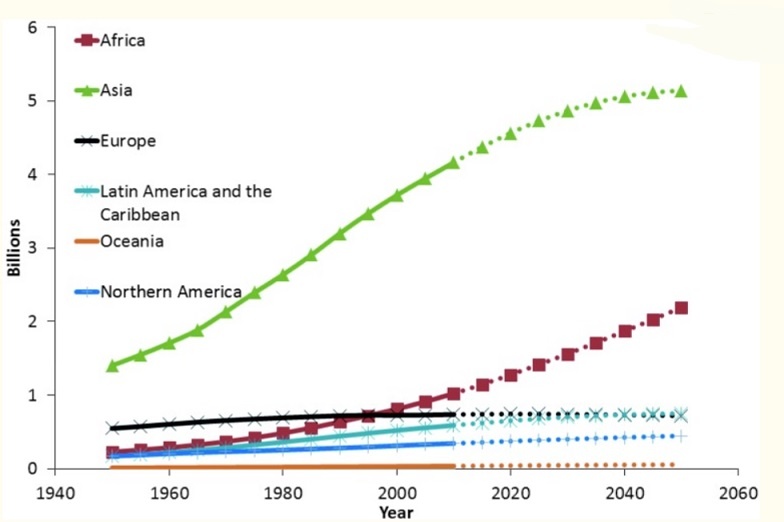

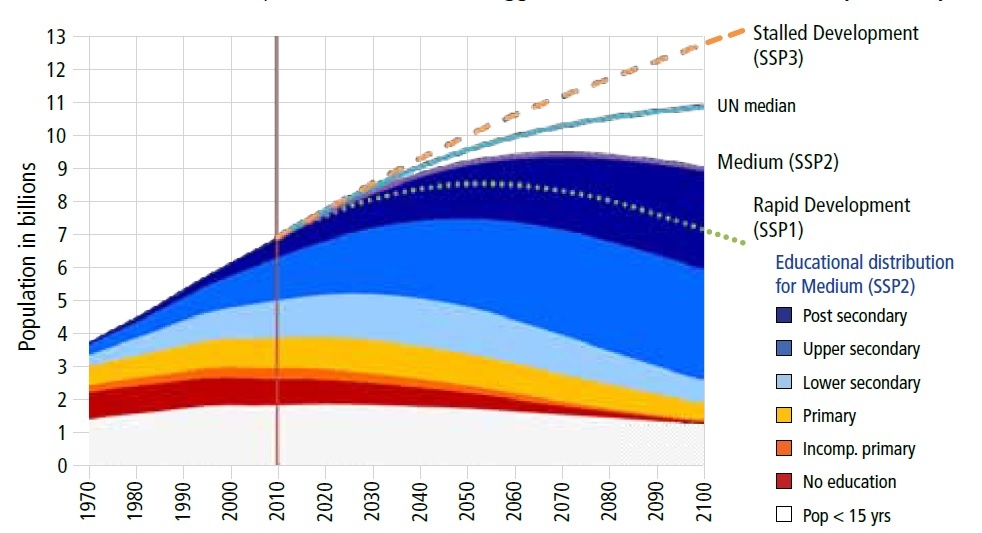

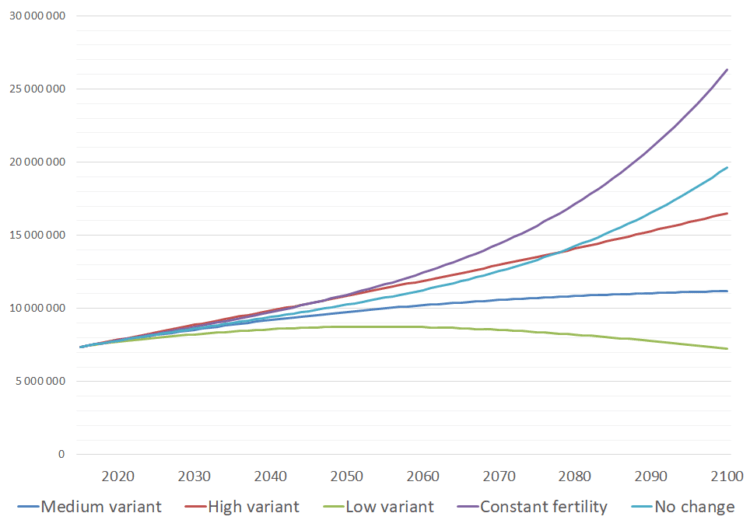

Figure above shows world population estimates from 1800 to 2100, based on “high”, “medium” and “low” United Nations projections in 2015 and UN historical estimates for pre-1950 data. According to the highest estimate, the world population may rise to 16 billion by 2100; according to the lowest estimate, it may decline to 6 billion. The median estimate for future growth sees the world population reaching 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100 assuming a continuing decrease in average fertility rate from 2.5 births per woman in 2010–2015 to 2.2 in 2045–2050 and to 2.0 in 2095–2100, according to the medium-variant projection. With longevity trending towards uniform and stable values worldwide, the main driver of future population growth is the evolution of the fertility rate.

_

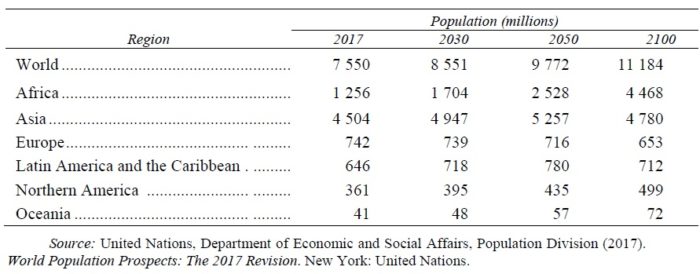

Population of the world and regions in 2017, 2030, 2050 and 2100 according to the medium variant projection in 2017:

Today, the world’s population continues to grow, albeit more slowly than in the recent past. Ten years ago, the global population was growing by 1.24 per cent per year. Today, it is growing by 1.08 per cent per year, yielding an additional 83 million people annually. The world’s population is projected to increase by slightly more than one billion people over the next 13 years, reaching 8.6 billion in 2030, and to increase further to 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100 (see table above).

Remember the Medium Variant is the projection that the UN researchers see as the most likely scenario.

_

By 2050 (medium variant), India will have 1.73 billion people, China 1.46 billion, Nigeria 401 million, United States 398 million, Indonesia 327 million, Pakistan 403 million, Bangladesh 265.8 million, Brazil 232 million, Democratic Republic of Congo 195.3 million, Ethiopia 188.5 million, Mexico 164 million, Philippines 157.1 million, Egypt 142 million, Russia 133 million, Tanzania 129.4 million, Vietnam 112.8 million, Japan 107 million, Uganda 101 million, Turkey 96 million, Kenya 95.5 million, Iran 95 million, Sudan 81 million, Germany 78 million and the United Kingdom and France 75 million.

_

Rapid population growth in Africa:

A key trend in future decades will be population growth in Africa. The continent’s population could quadruple over the next century, rising from 1 billion inhabitants in 2010 to an estimated 2.5 billion in 2050 and more than 4 billion in 2100, despite the negative impact of the AIDS epidemic and other factors. While, globally speaking, one person in six currently lives in Africa, the proportion will probably be more than one in three a century from now. Growth should be especially rapid in sub-Saharan Africa, where the population may rise from just over 800 million in 2010 to 4 billion in 2100.

More than half of global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa. Africa has the highest rate of population growth among major areas. A rapid population increase in Africa is anticipated even if there is a substantial reduction of fertility levels in the near future. The strong growth of the African population will happen regardless of the rate of decrease of fertility, because of the exceptional proportion of young people already living today. For example, the UN projects that the population of Nigeria will surpass that of the United States by 2050.

_

Shrinking population in Europe:

In sharp contrast to Africa, the populations of 55 countries or areas in the world are expected to decrease by 2050, of which 26 may see a reduction of at least ten per cent. Several countries are expected to see their populations decline by more than 15 per cent by 2050, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine. Fertility in all European countries is now below the level required for full replacement of the population in the long run (around 2.1 children per woman), and in the majority of cases, fertility has been below the replacement level for several decades.

_____

Factors influencing the population growth:

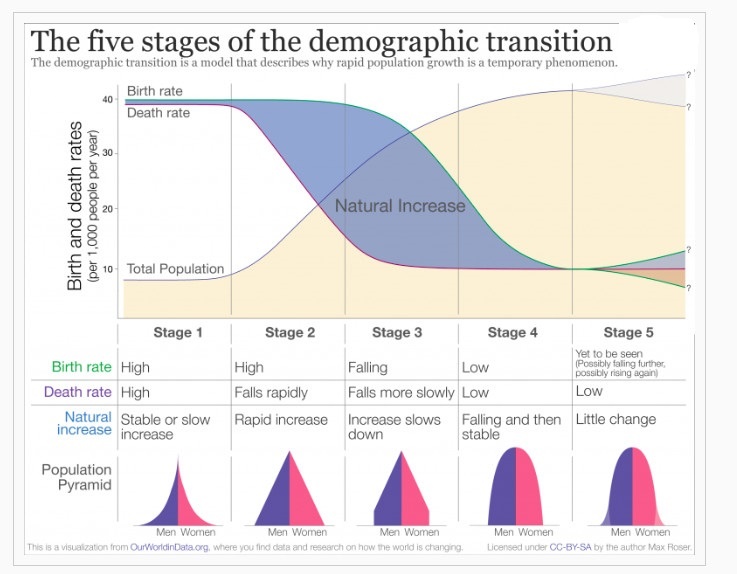

Population of any country increases or decreases because of three main demographic factors: (a) birth rate, (b) death rate, and (c) migration. A number of socio-economic factors also influence birth rate and death rate which ultimately affect population change.

Birth Rate: The number of births per thousand of population in a given year under a particular territory is called Crude Birth Rate (popularly known as birth rate).

Death Rate: The number of deaths per thousand of population in a given year under a particular territory is called Crude Death Rate (popularly known as death rate).

Natural Growth Rate: Natural growth rate is the difference between birth rate and death rate. Therefore, natural growth rate = birth rate – death rate.

Suppose the birth rate of a particular year within an area is 32 and death rate is 24. Therefore, natural growth rate is 32 – 24 = 8 per thousand of population. Population growth rate is in percentage i.e. 0.8 %. (8 per thousand is 0.8 per hundred) In other words, birth rate minus death rate divided by 10 gives population growth rate in percentage excluding migration.

When the birth rate is higher than the death rate, population increases. When the death rate is more than the birth rate, population decreases. When the two rates are equal, the population remains constant. Thus, the birth and death rates affect the balance of population.

_

When demographers attempt to forecast changes in the size of a population, they typically focus on four main factors: fertility rates, mortality rates (life expectancy), the initial age profile of the population (whether it is relatively old or relatively young to begin with) and migration. In the case of religious groups, a fifth factor is switching – how many people choose to enter and leave each group, including how many become unaffiliated with any religion.

Fertility rates:

Future population growth is highly dependent on the path that future fertility will take. According to the World Population Prospects (2019 Revision), global fertility is projected to fall from 2.5 children per woman in 2019 to 2.2 in 2050. As a result of declining fertility rates, global population growth is slowing. Over the four decades from 1970 to 2010, the number of people on Earth grew nearly 90%. From 2010 to 2050, the world’s population is expected to rise 35%, from roughly 7 billion to more than 9 billion.

Life expectancy:

People in many (though not all) countries are living longer due to increased access to healthcare, improvements in diet and hygiene, effective responses to infectious disease, and many other factors. These developments in healthcare and living conditions, however, have not occurred uniformly around the world. Overall, significant gains in life expectancy have been achieved in recent years. Globally, life expectancy at birth is expected to rise from 72.6 years in 2019 to 77.1 years in 2050. While considerable progress has been made in closing the longevity differential between countries, large gaps remain. In 2019, life expectancy at birth in the least developed countries lags 7.4 years behind the global average, due largely to persistently high levels of child and maternal mortality, as well as violence, conflict and the continuing impact of the HIV epidemic. Life expectancy is a significant factor in estimating the size of the world’s populations over time. Groups with higher life expectancies will, on average, live longer and (all else remaining equal) have larger populations.

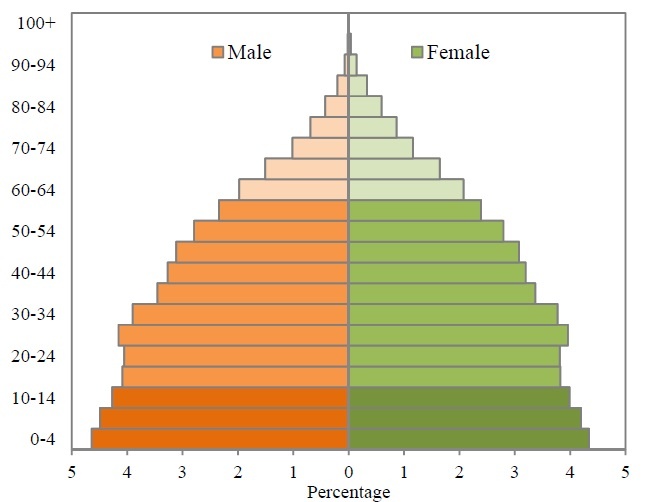

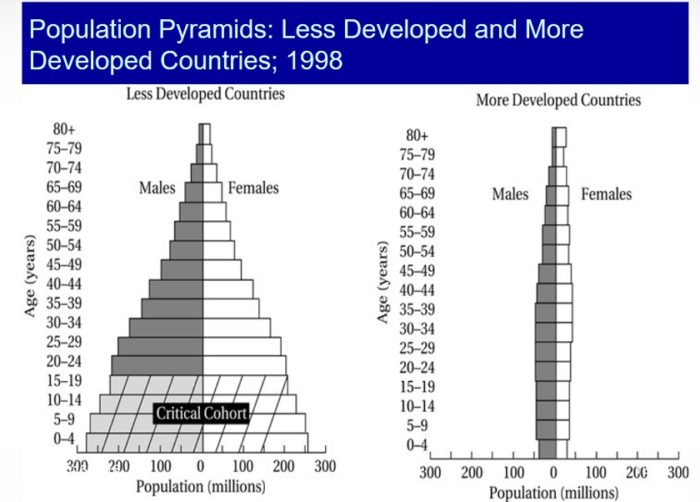

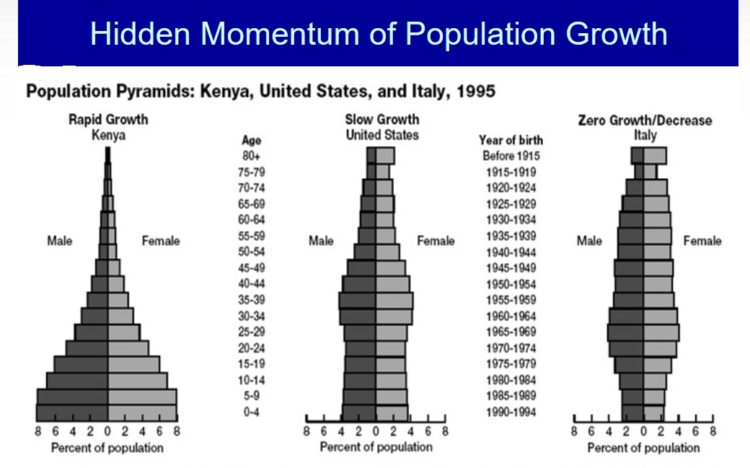

Age structure:

All else being equal, a population that begins with a relatively large percentage of people who are in – or soon will enter – their prime childbearing years will grow faster than a population that begins with many people who are beyond their prime reproductive years. Moreover, growth propelled by a youthful population tends to carry into the next generation, as the younger cohort’s children reach maturity and begin to have babies of their own, creating a kind of demographic momentum.

International migration:

International migration is a much smaller component of population change than births or deaths. However, in some countries and areas the impact of migration on population size is significant, namely in countries that send or receive large numbers of economic migrants and those affected by refugee flows. Between 2010 and 2020, fourteen countries or areas will see a net inflow of more than one million migrants, while ten countries will see a net outflow of similar magnitude.

Projected migration to developed countries:

According to the United Nations, during 2005–2050 the net number of international migrants trying to reach more developed regions is projected to be 98 million, so the population in those regions will likely be influenced by international migration. Deaths are projected to exceed births in the more developed regions by 73 million during 2005–2050. In 2000–2005, net migration in 28 countries either prevented population decline or doubled at least the contribution of natural increase (births minus deaths) to population growth. These countries include Austria, Canada, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Qatar, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom.

______

______

Birth rate:

The birth rate (technically, births/population rate) is the total number of live births per 1,000 in a population in a year or period. The rate of births in a population is calculated in several ways: live births from a universal registration system for births, deaths, and marriages; population counts from a census, and estimation through specialized demographic techniques. The birth rate (along with mortality and migration rate) are used to calculate population growth.

The crude birth rate is the number of live births per year per 1,000 mid-year population. When the crude death rate is subtracted from the crude birth rate, the result is the rate of natural increase (RNI). This is equal to the rate of population growth (excluding migration).

The average global birth rate is 18.5 births per 1,000 total population in 2016. The death rate is 7.8 per 1,000 per year. The RNI is thus 10.7 per thousand or 1.07 %.

The 2016 average of 18.5 births per 1,000 total population is estimated to be about 4.3 births/second or about 256 births/minute for the world.

_

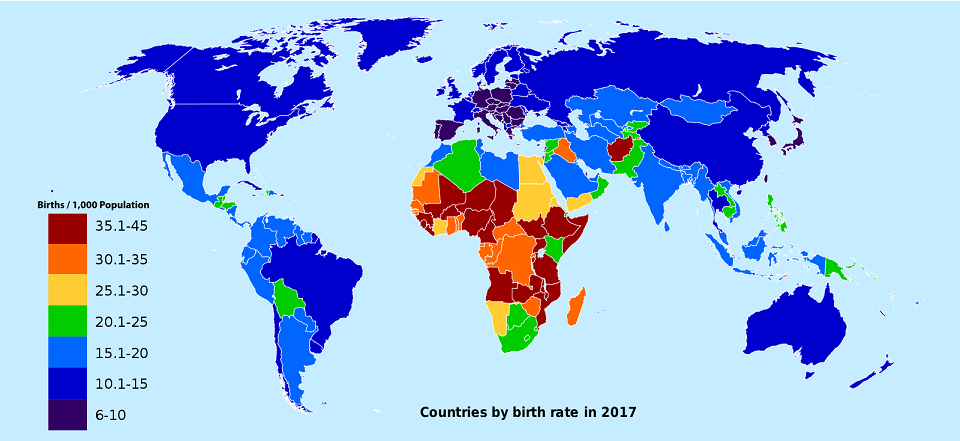

Figure below shows countries by crude birth rate (CBR) in 2017:

Africa has the highest birth rates.

_

Factors affecting birth rate:

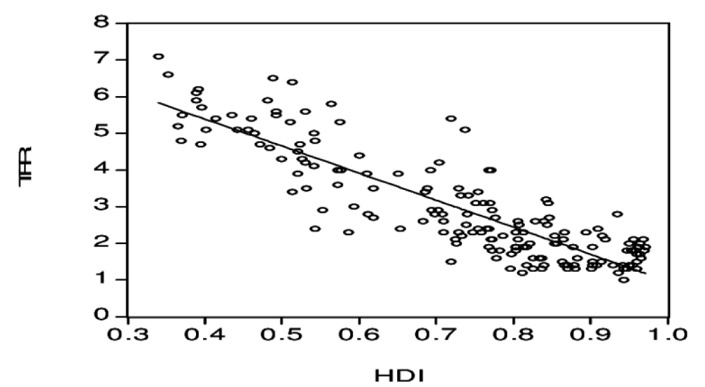

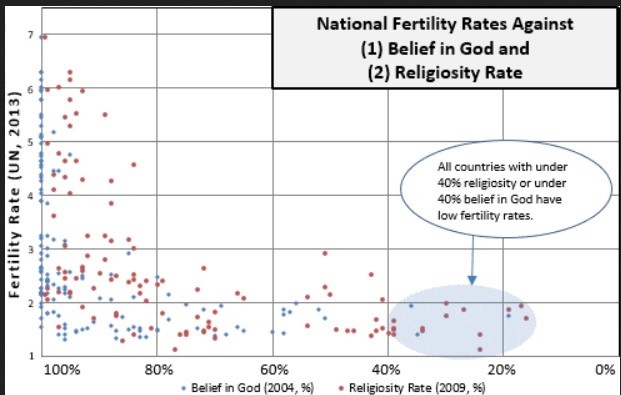

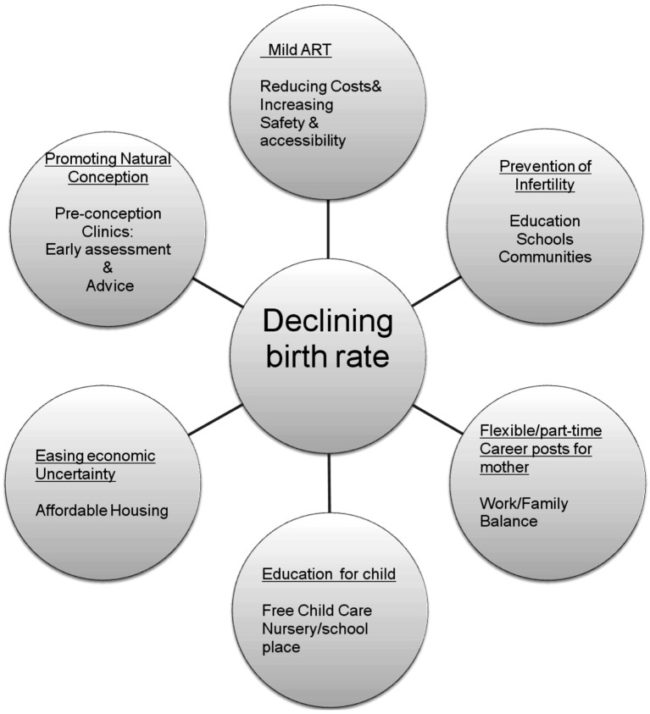

There are many factors that interact in complex ways, influencing the births rate of a population. Developed countries have a lower birth rate than underdeveloped countries. A parent’s number of children strongly correlates with the number of children that each person in the next generation will eventually have. Factors generally associated with increased fertility include religiosity, intention to have children, and maternal support. Factors generally associated with decreased fertility include wealth, education, female labor participation, urban residence, intelligence, increased female age, women’s rights, access to family planning services and (to a lesser degree) increased male age. Many of these factors however are not universal, and differ by region and social class. For instance, at a global level, religion is correlated with increased fertility, but in the West less so: Scandinavian countries and France are among the least religious in the EU, but have the highest TFR, while the opposite is true about Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Poland and Spain.

Reproductive health can also affect the birth rate, as untreated infections can lead to fertility problems, as can be seen in the “infertility belt” – a region that stretches across central Africa from the United Republic of Tanzania in the east to Gabon in the west, and which has a lower fertility than other African region.

_

In the 20th Century, the world’s birth rate dropped from 40 births per 1,000 people per year to just 31 in 1995, and today it is only 18.5. But long ago, humans needed a birth rate of about 80 births per 1,000 people per year in order to survive, because people didn’t live so long and far fewer of those born had children. Today, life expectancy is about 70 years and for most of human history that was not the case. There are some estimates for the Middle Ages where life expectancy might have been 10-12 years, which means many people never made it out of childhood. Even if you had a lot of births, many of those never lived to actually bear children themselves. That estimate of 80 births per 1,000 people per year looks very high by today’s standards – but in fact it is conservative, implying a very slow population growth, much slower than anything we see today.

______

Why do death rates decline?

Except for a 10-year period between 1955 and 1965 when the mortality rate was essentially flat, mortality rates have declined at the relatively constant rate of approximately 1 to 2 percent per year since 1900. That mortality reduction used to be concentrated at younger ages, but then became increasingly concentrated among the aged. In the first four decades of the twentieth century, 80 percent of life expectancy improvements resulted from reduced mortality for those below age 45, the bulk of these for infants and children. In the next two decades, life expectancy improvements were split relatively evenly by age group. In the latter four decades of the century, about two-thirds of life expectancy improvements resulted from mortality reductions for those over age 45.

During the first half of the twentieth century, changes in the ability to avoid and withstand infectious diseases were the prime factors in reducing mortality. Infectious diseases were the leading cause of death in 1900, accounting for 32 percent of deaths. Pneumonia and influenza were the biggest killers. Therefore, improved nutrition and public health measures, particularly important for the young, were vastly more important in this period than medical interventions. Better nutrition allowed people to avoid contracting disease and to withstand disease once contracted; public health measures reduced the spread of disease. During this period, reduced infant mortality contributed 4.5 years to overall improvements in life expectancy; reduced child mortality contributed nearly as much, and reduced mortality among young adults added about 3.5 years.

Between 1940 and 1960, infectious diseases as a cause of death continued to decline. But more of this decline was attributable to medical factors, such as the use of penicillin, sulfa drugs (discovered in 1935), and other antibiotics. These help the elderly as well as the young, thereby reducing mortality across the age spectrum. By 1960, 70 percent of infants could be expected to survive to age 65.

Since 1960, mortality reductions have been associated with two newer factors: the frequent conquest of cardiovascular disease in the elderly and the prevention of death caused by low birth weight in infants. Traditional killers such as pneumonia in the young also have continued to decline, but mortality from these causes was already so low that further improvements did not add greatly to overall longevity.

Increasingly, mortality reductions are attributed to medical care, including high tech medical treatment, and not to social or environmental improvements. Smoking cessation and better diets also are factors: per capita consumption of cigarettes rose from essentially zero in 1900 to more than 4,000 per year per capita in 1960, or over two packs per smoker per day. Since then, per capita consumption has fallen by more than 50 percent. These trends affect death from heart disease and from smoking-sensitive cancers with a 10 to 20-year lag.

For several important causes of death, rising incomes and a variety of social programs have accompanied significant reductions in mortality.

______

Population growth rate:

Population growth rate is the rate at which the no. of individuals in a population increases in a given time period, expressed as a fraction of the initial population. Population growth rate is the average annual percent change in the population, resulting from a surplus (or deficit) of births over deaths and the balance of migrants entering and leaving a country. A positive growth rate indicates that the population is increasing, while a negative growth rate indicates that the population is decreasing. A growth ratio of zero indicates that there were the same number of individuals at the beginning and end of the period—a growth rate may be zero even when there are significant changes in the birth rates, death rates, immigration rates, and age distribution between the two times. The rate of national population growth is expressed as a percentage for each country, commonly between about 0.1% and 3% annually. Current Indian population growth rate is 1.38 % which should become zero or even negative to control population.

_

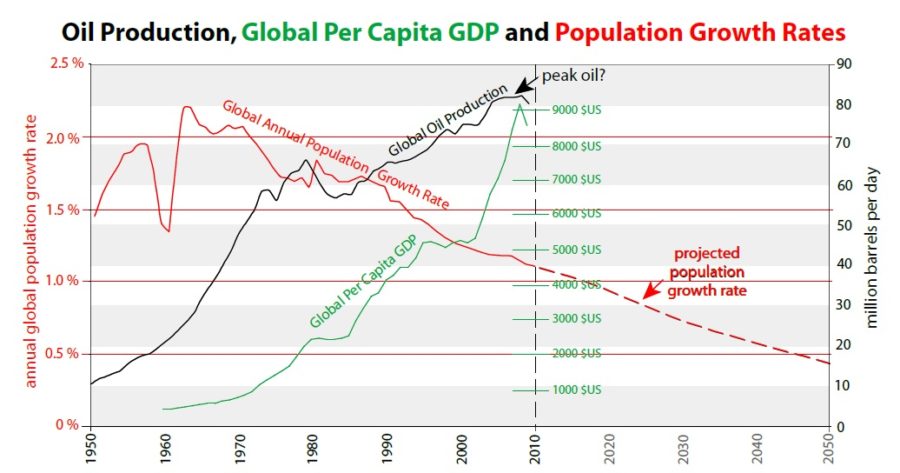

The world population is currently growing by approximately 83 million people each year. Within many populations of the world, growth rates are slowing, resulting in the global population growth rate decreasing as below:

| 1995 | 1.55% |

| 2005 | 1.25% |

| 2015 | 1.18% |

| 2017 | 1.12% |

Population in the world is currently (2019-2020) growing at a rate of around 1.08% per year (down from 1.10% in 2018, 1.12% in 2017 and 1.14% in 2016).

_

Calculate Population’s Growth Rate:

Calculate population growth rate by dividing the change in population by the initial population, multiplying it by 100, and then dividing it by the number of years over which that change took place. The number is expressed as a percentage.

Population growth rates are used for many sizes of geographic areas from a specific neighborhood to the world. These rates take into account the births and deaths occurring during the specified time along with people who move into and out of the area. I have shown before that you can get population growth rate by subtracting death rate from birth rate and dividing it by 10. This is natural population growth rate and this population growth rate is not taking migration into account.

_

Natural Growth vs. Overall Growth:

You’ll find two percentages associated with population – natural growth and overall growth. Natural growth represents the births and deaths in a country’s population and does not take into account migration. The overall growth rate takes migration into account.

For example, Canada’s natural growth rate is 0.3% while its overall growth rate is 0.9%, due to Canada’s open immigration policies. In the U.S., the natural growth rate is 0.6% and overall growth is 0.9%.

The growth rate of a country provides demographers and geographers with a good contemporary variable for current growth and for comparison between countries or regions. For most purposes, the overall growth rate is more frequently utilized.

_

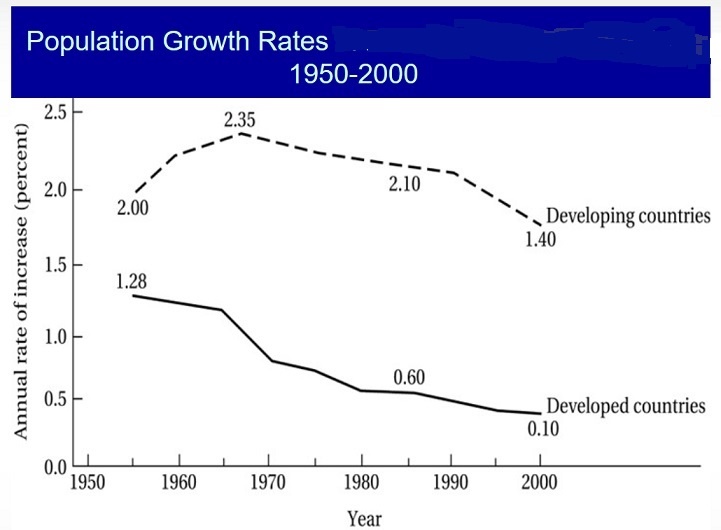

The annual population growth rate actually peaked half a century ago at more than 2%, and has fallen by half since then, to 1.12 % in 2017 (see figure below). This trend should continue in coming decades because fertility is decreasing at global level, from 5 children per woman in 1950 to 2.5 today. In 2017, the regions where fertility remains high (above 3 children per woman) include most countries of intertropical Africa and an area stretching from Afghanistan to northern India and Pakistan. These are the regions that will drive future world population growth.

_

Doubling Time:

The growth rate can be used to determine a country or region’s — or even the planet’s — “doubling time,” which tells us how long it will take for that area’s current population to double. This length of time is determined by dividing 70 by growth rate. The number 70 comes from the natural log of 2, which is 0.70.

The doubling time is not constant. Humans reached 1 billion around 1800, a doubling time of about 300 years; 2 billion in 1927, a doubling time of 127 years; and 4 billion in 1974, a doubling time of 47 years.

Given Canada’s overall growth of 0.9% in the year 2006, we divide 70 by 0.9 (from the 0.9%) and yield a value of 77.7 years. Thus, in 2083, if the current rate of growth remains constant, Canada’s population will double from its current 33 million to 66 million. However, if we look at the U.S. Census Bureau’s Demographic Data for Canada, we see that Canada’s overall growth rate is expected to decline to 0.6% by 2025. With a growth rate of 0.6% in 2025, Canada’s population would take about 117 years to double (70 / 0.6 = 116.666).

_____

Patterns of population growth:

The LEDC (Less Economically Developed Country) sector includes countries with a lower GDP and a lower standard of living than MEDC (More Economically Developed Country) countries. Indicators used to classify countries as LEDC or MEDC include industrial development and education. Rates of population growth vary across the world. Although the world’s total population is rising rapidly, not all countries are experiencing this growth. In the UK, for example, population growth is slowing, while in Germany the population has started to decline. MEDCs have low population growth rates, with low death rates and low birth rates. LEDCs have high population growth rates. Both birth rates and death rates in LEDCs tend to be high. However, improving healthcare leads to death rates falling – while birth rates remain high.

The tables below show data in selected LEDC and MEDC countries.

| MEDC | Birth rate | Death rate | Natural increase | Population growth rate (%) |

| UK | 11 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Canada | 11 | 7 | 4 | 0.4 |

| Bulgaria | 9 | 14 | -5 | -0.5 |

| LEDC | Birth rate | Death rate | Natural increase | Population growth rate (%) |

| South Africa | 25 | 15 | 10 | 1 |

| Botswana | 31 | 22 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Zimbabwe | 29 | 20 | 9 | 0.9 |

_

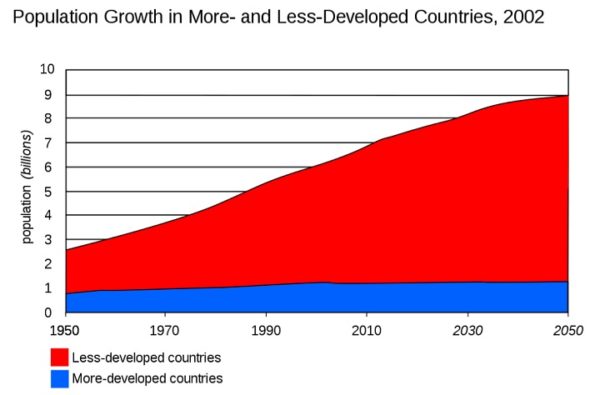

Population Growth in Developed and Developing Countries:

Let us look into the contrasting features of population growth in the developing and developed countries of the world.

By the middle of 2012, growth of world population was 7.058 billion (bn), 84 per cent of which (5.93 bn) are in the developing and poor nations of Asia, Africa and Latin America. In other words, world population growth is far from systematic as nearly 37per cent (2.6 bn) of world population is in two developing countries, viz. China (1.35 bn) and India (1.25bn) only. Data reveal the tragic aspect of population growth: poorer the country, the higher the rate of population growth. The more developed countries of the West today have low death (10 per 1000 population) and low birth rate (11 per 1000 population). One important reason for such a demographic transition is the high standard of life of their population as revealed in their HDI rank and Gross National Income in Purchasing Power Parity (GNI PPP) per capita. But, due to steadily declining population, these societies are also faced with strains of fading and aging populations. Changes in the composition of population during the last century also have left adverse effect on the environment because different population subgroups behave differently and their requirements also differ. This aspect of the population– development relation once again reminds us about the fact that population is a prerequisite to development only to the extent that a society requires more manpower to carry out its developmental activities.

_

Figure below shows difference in population growth rates between developed and developing countries:

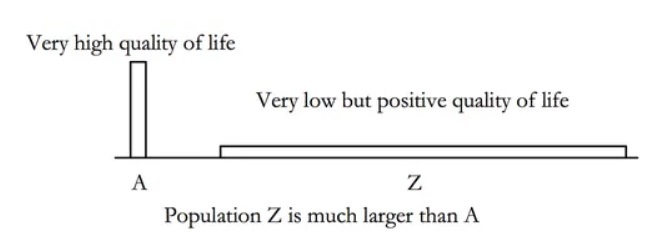

_