Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Sexual Harassment:

_____

_____

Prologue:

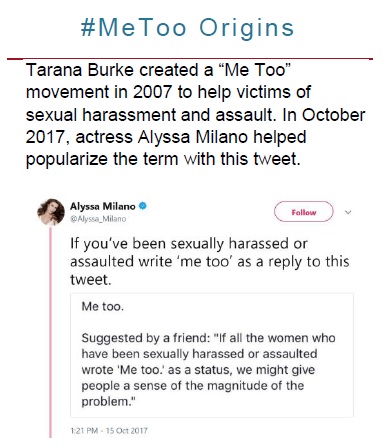

In October 2016, a month before the presidential election, a 2005 tape came to the public’s attention. In raw footage from behind the scenes on Access Hollywood, Republican candidate Donald Trump bragged boldly about kissing women without their consent, grabbing at their genitals, and simply having his way: “…when you’re a star, they let you do it.” In a subsequent debate, CNN’s Anderson Cooper called the actions that Trump described “sexual assault.” Trump called it “locker room talk.” Whatever the term, the behavior and the attitude ultimately proved inconsequential, not sufficiently meaningful or outrageous to derail Trump’s election victory. In January 2017, Trump took up the position as the most powerful man in the world. Yet, almost exactly one year later, scores of women are stepping up and speaking out. They tell heart-breaking, terrifying stories of sexual harassment, and sexual assault at the hands of powerful men – in Hollywood and New York, in politics and journalism, in religious and educational institutions – taking advantage of their powerful positions. One by one, by the thousands, women are joining around #MeToo to lend support to each other and voice their outrage, intent on being silenced no more. As the #MeToo movement gathers momentum in India, allegations of sexual harassment have surfaced against union minister of state for external affairs M.J. Akbar who has been accused of sexual harassment by many women journalists when he was editor.

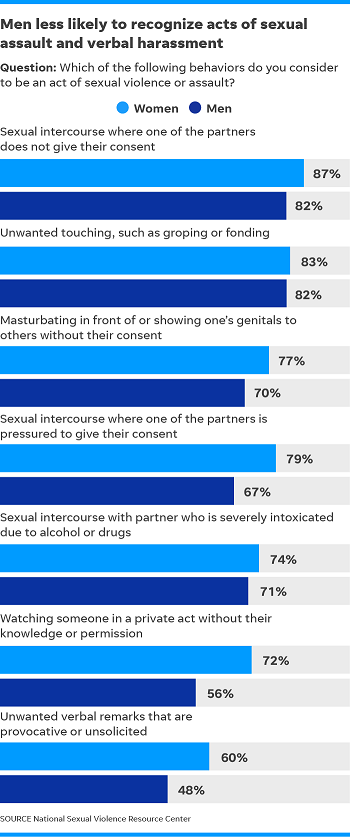

Although majority of victims are women, the victim, as well as the harasser, may be a woman or a man. The victim does not have to be of the opposite sex. The level of tolerance for sexual harassment varies from culture to culture. We need to focus more on this problem, because a lot of men still don’t take it seriously. Men and women view it differently. When 1200 men and women were asked if they would consider sexual proposition flattering, 68% of men said they would, and only 17% of the women agreed. At the same time 63% of women would be insulted by it and only 15% of men.

I have already posted articles on ‘the rape’, ‘sex trafficking’ and ‘scientific punishment for rape’ on this website, and today I am posting article on ‘sexual harassment’ which is far more common than rape. Although few authors have classified rape as a type of sexual harassment, sexual harassment is distinct from rape, and sexual harassment may lead to rape.

I quote myself from my article ‘scientific punishment for rape’:

“Libido (sex drive) is a strong instinct. Thoughts about sex are constantly swirling in the minds of most men. Even seers are not exempt from it. Fulfilment of a sexual desire is a natural quest. All men have sexual desire but many do not rape despite getting an opportunity because their neo-cortex is trained by culture, religion, education, society, fear of laws and good upbringing to override sub-cortical sex drives. We ought to teach and train neo-cortex of our teens to control sub-cortical biological sex drive as they reach puberty, and to respect women. Rape is about mind-set of men and we need to change that mind-set. Better upbringing, better education, better neighbourhood, better peers and better society can change that mind-set”.

About 80 women accused Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment in 2017. When movie stars don’t know where to go, what hope is there for the rest of women? What hope is there for the janitor who’s being harassed by a co-worker but remains silent out of fear she’ll lose the job she needs to support her children? For the administrative assistant who repeatedly fends off a superior who won’t take no for an answer? For the hotel housekeeper who never knows, as she goes about replacing towels and cleaning toilets, if a guest is going to corner her in a room she can’t escape? Is sexual harassment all about fulfilment of sexual desire even if unwanted by victim, or is it about power and dominance over victim or both?

_____

Abbreviations and synonyms:

SSH = Stop Street Harassment (a non-profit organization)

ICC = Internal Complaint Committee

HR = Human Resources

OCR = Office of Civil Rights

EEOC = Equal Employment Opportunities Commission

PISB = Patient-initiated sexual behaviors

SEQ = Sexual Experiences Questionnaire

PCSH = Psychological Climate for Sexual Harassment

_____

Note:

Historically, the terms “sex” and “gender” have been used interchangeably, but their uses are becoming increasingly distinct, and it is important to understand the differences between the two. Sex or sexuality refers to the physiological, biological characteristics of a person, with a focus on sexual reproductive traits, wherein males have male sexual traits (penis, testes, sperm) and females have female sexual traits (vagina, ovaries, eggs). Gender on the other hand primarily deals with personal, societal and cultural perceptions of sexuality.

______

______

Read these powerful, inspirational quotes to encourage you to fight against sexual harassment:

“Don’t be ashamed of your story it will inspire others”

-Anonymous

_

“Forgetting is difficult. Remembering is worse”

-Anonymous

_

“I can be changed by what happens to me, but I refuse to be reduced by it”

-Maya Angelou

_

“You took away my worth, my privacy, my energy, my time, my safety, my intimacy, my confidence, my own voice, until now”

-Anonymous

_

“She was powerful, not because she wasn’t scared but because she went on so strongly despite the fear”

-Atticus

_

“Today in science class I learned every cell in our entire body is replaced every seven years. How lovely it is to know one day I will have a body you will never have touched”

-L.M.

_

“I am not what happened to me. I am what I choose to become”

-Carl Jung

_

“I will never understand why it is more shameful to be raped than to be a rapist”

-Anonymous

_

“Beauty provokes harassment, the law says, but it looks through men’s eyes when deciding what provokes it.”

-Naomi Wolf

_

“If your flirting strategy is indistinguishable from harassment, it’s not everyone else that’s the problem.”

-John Scalzi

_

“Women who accuse men, particularly powerful men, of harassment are often confronted with the reality of the men’s sense that they are more important than women, as a group.”

-Anita Hill

_

“He told me he was used to getting what he wanted.”

-Celia Conrad

_

“You know… You’re still my boss… Which means… This is sexual harassment…Oh really? I guess I’ll have to fire you then.”

-Alexandra V.

_

A woman who was interviewed by sociologist Helen Watson said, “Facing up to the sexual harassment and having to deal with it in public is probably worse than suffering in silence. I found it to be a lot worse than the harassment itself.”

______

______

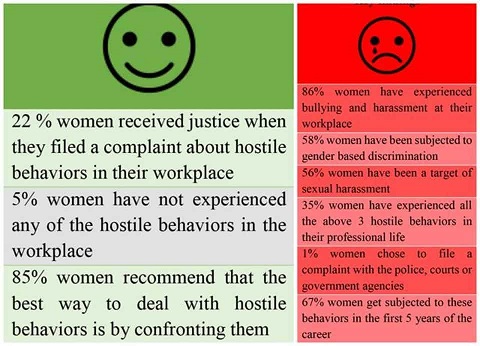

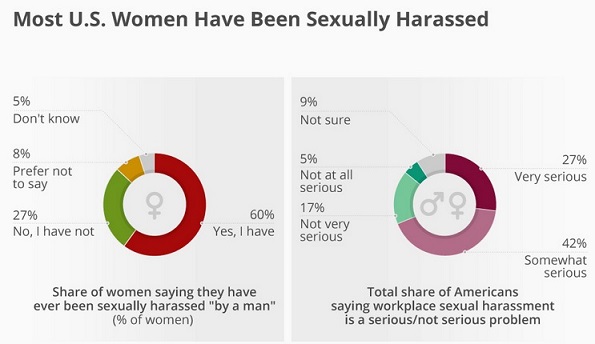

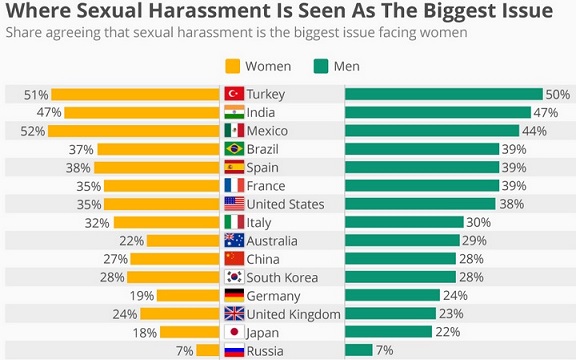

One of the unfortunate consequences of the ever-growing number of women joining the labour force and working side by side with men is the increasing number of sexual harassment cases all over world. It is very difficult to find a woman who has never ever encountered sexual harassment of one kind or another, whether it’s a wolf whistle, sexual touch or outright sexual favour. While sexual harassment has been a pervasive problem for women throughout history, only in the past few decades have feminist litigators won definition of sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination and have women come forward in droves to demand remedies and institutional change. Women around the world are beginning to tell their stories and expose the pervasiveness of sexual harassment in their societies. A 1992 International Labor Organization survey of 23 countries revealed what women already know: that sexual harassment is a major problem for women all over the world. A recent poll found that such experiences are a brutal reality across the United States, and 60 percent of all U.S. women have been sexually harassed by a man at some point while 27 percent have not and 8 percent prefer not to say. In India, 90% of the total female workforce is engaged in the informal economy. The incidences of sexual harassment of women workers in workplaces such as construction sites, informal vendor markets, residential complexes, agricultural fields and small-sized factories go unnoticed. Unaware of legal recourses and fearing societal indignity, they just succumb to the might of men. Sexual harassment at informal workplaces should be included in all debates and discussions.

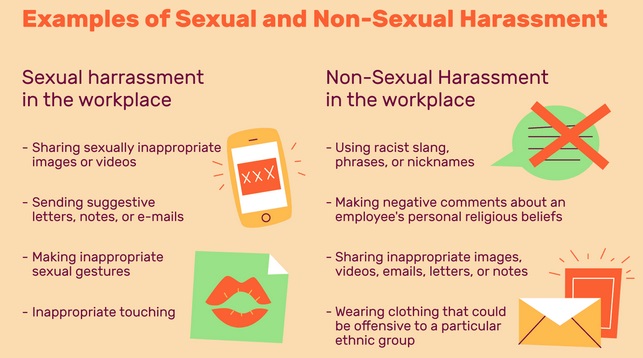

______

Sexual harassment means any unwelcome sexual advance, unwelcome request for sexual favours, or other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature which makes a person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated, and where that reaction is reasonable in the circumstances. Examples of sexual harassment include, but are not limited to,

- staring or leering

- unnecessary familiarity, such as deliberately brushing up against you or unwelcome touching

- suggestive comments or jokes

- insults or taunts of a sexual nature

- intrusive questions or statements about your private life

- displaying posters, magazines or screen savers of a sexual nature

- sending sexually explicit emails or text messages

- inappropriate advances on social networking sites

- accessing sexually explicit internet sites

- requests for sex or repeated unwanted requests to go out on dates

- behaviour that may also be considered to be an offence under criminal law, such as physical assault, indecent exposure, sexual assault, stalking or obscene communications

_____

Now let me show you some pictures of sexual harassment:

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

______

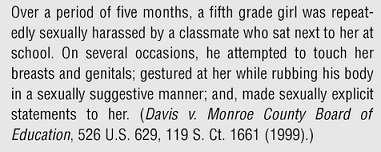

Following are some examples of sexual harassment:

- Susan

Susan recently took a job in the skilled trades. The men on the job make lewd sexual remarks and refuse to cooperate with Susan on job assignments. They tell her if she’s “so good” she can do the job herself. She finds obscene messages pasted to her locker, her work bench, and in her tool kit. Her supervisor suggests if she can’t “take a little fun” she should transfer to a new assignment.

- June

June worked as a sales person at a retail establishment. Two male co-workers tell dirty jokes of a sexual nature to her and make lewd remarks. She tried to ignore the comments by walking away. The verbal comments increased, and one co-worker began to touch her in sexually suggestive ways. June complained to her manager, who said he “would take care of it”, but the harassment became worse over the next few weeks. June felt forced to leave her employment.

- Joan

Joan works in a company as a custodial worker. She has been employed only a short time when a male co-worker begins making obscene sexual remarks to her. She tells him to leave her alone, and he reacts by forcing her into a locker room to cooperate with his sexual demands. She complains to her supervisor, but her supervisor tells her that he can’t do anything and that she should “work it out.” The next day Joan is subjected to the same verbal and physical threats.

- Sam

Sam works for a firm in Sales and has to travel to other cities with his boss. The boss wants to share a hotel room “to save the company some money.” When Sam refuses she tells him to stop “acting like a baby” and “smarten up”. She later gives him a poor performance evaluation, and he is terminated shortly afterwards.

_

5.

_

6.

_

7.

_

8.

_

9.

_

- A woman has walked alone down the street when a man follow her for two blocks repeating “God bless you, beautiful,” “God bless your beautiful body,” and “God made you so beautiful.” Anything said to a woman by the man under the protection of “God” is just as threatening as any other kind of sexual comment. And to the people for whom God is a special thing, using him as a weapon of harassment is doubly offensive.

_

Any of the examples above represent sexual harassment. In all cases it is the consequences – not the intentions – that count. The severity of the harassment is largely determined by the impact it has on the victim. So “It was just a joke” or “I had too much to drink” is no excuse and no defence. According to the law, actual intent is irrelevant; what is relevant is the impact the behavior has on the recipient. Harassment usually relates to intimidation, exploitation and power; not to real, mutual personal attraction and respect. Thus a relationship between two consenting adults would usually not be harassment. Yet if the one party has far more power than the other, and abuses this in the work situation to coerce the other, it could still be harassment. If unwelcome attentions have been declined, but are repeated, or if the person is victimised because of having refused advances, the situation becomes worse.

_

Varied behaviors:

One of the difficulties in understanding sexual harassment is that it involves a range of behaviors. In most cases (although not in all cases) it is difficult for the victim to describe what they experienced. This can be related to difficulty classifying the situation or could be related to stress and humiliation experienced by the recipient. Moreover, behavior and motives vary between individual cases.

_______

_______

Terminology:

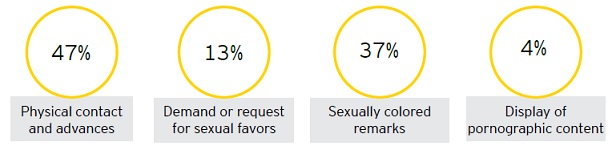

The terms “sexual abuse,” “sexual assault,” “sexual harassment” – and even “rape” – crop up daily in the news. We are likely to see these terms more as the #MeToo movement continues. Many people want to understand these behaviors and work to prevent them. It helps if we are consistent and as precise as possible when we use these terms. Let’s start by defining each of these terms. Then, we can look at how these behaviors sometimes overlap.

_

Discriminatory behavior:

An umbrella term that includes biased treatment based upon characteristics such as race, color, ethnicity, age, sex, and so on. This term includes the different forms of sexual harassment, as well as other forms of sex/gender discrimination.

_

Sexism:

Sexism is an attitude. It is an attitude of a person of one sex that he or she is superior to a person of the other sex.

For example, a man thinks that women are too emotional. Or a woman thinks that men are chauvinists.

_

Sex/gender discrimination:

A broad term that includes discrimination and harassment based upon gender or sex. In addition to sexually harassing behavior, examples of this include pay or hiring discrimination based on one’s sex or gender.

_

Consent:

Consent is a clear, knowing and voluntary decision to engage in sexual activity. Because consent is voluntary, it is given without coercion, force, threats, or intimidation. It is given with positive cooperation in the act or expression of intent to engage in the act pursuant to an exercise of free will. Consent is active, not passive. Silence, in and of itself, cannot be interpreted as consent. Consent can be given by words or actions, as long as those words or actions consist of an affirmative, unambiguous, conscious decision by each participant to engage in mutually agreed-upon sexual activity. Consent is revocable, meaning consent can be withdrawn at any time. Thus, consent must be ongoing throughout a sexual encounter. Once consent has been revoked, sexual activity must stop immediately.

_

Non-Consensual Sexual Contact:

Non-consensual sexual contact is any intentional sexual touching, however slight, with any object by a male or female upon a male or a female that is without consent and/or by force. Sexual Contact includes intentional contact with the breasts, buttock, groin, or genitals, or touching another with any of these body parts, or making another touch you or themselves with or on any of these body parts; any intentional bodily contact in a sexual manner, though not involving contact with/of/by breasts, buttocks, groin, genitals, mouth or other orifice.

_

Non-Consensual Sexual Intercourse:

Non-consensual sexual intercourse is any sexual intercourse however slight, by a male or female upon a male or a female that is without consent and/or by force. Intercourse includes vaginal penetration by a penis, object, tongue or finger; anal penetration by a penis, object, tongue, or finger; and oral copulation (mouth to genital contact or genital to mouth contact), no matter how slight the penetration or contact.

_

Sexual assault:

According to the United States Department of Justice, sexual assault is “any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient.” Sexual assault is basically an umbrella term that includes sexual activities such as rape, fondling, and attempted rape. However, the legal definition varies depending on which state you’re in, and can even be different depending on where you were when the assault happened.

_

Rape:

In 2012, the FBI issued a revised definition of rape as “penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.” The revised law is gender neutral, meaning that anyone can be a victim.

_

Sexual Exploitation:

Occurs when a person takes non-consensual or abusive sexual advantage of another for his/her own advantage or benefit, or to benefit or advantage anyone other than the one being exploited, and that behavior does not otherwise constitute one of other sexual misconduct offenses.

_

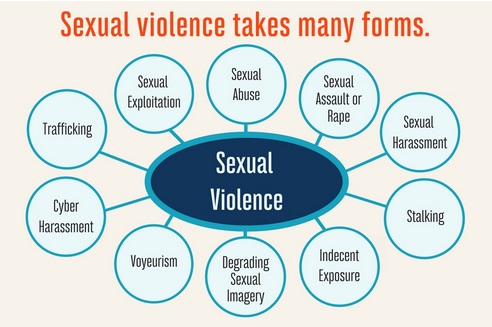

Sexual violence:

The World Health Organization (WHO) in its 2002 World Report on Violence and Health defined sexual violence as: “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.” Sexual violence include rape, sexual abuse, sexual harassment and intimidation at work, in educational institutions and elsewhere, trafficking in women and forced prostitution.

_

Sexual abuse:

Sexual abuse, also referred to as molestation, is usually undesired sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. When force is immediate, of short duration, or infrequent, it is called sexual assault. The offender is referred to as a sexual abuser or (often pejoratively) molester. The term also covers any behavior by an adult or older adolescent towards a child to stimulate any of the involved sexually. The use of a child, or other individuals younger than the age of consent, for sexual stimulation is referred to as child sexual abuse or statutory rape.

_

Stalking:

Stalking is unwanted or repeated surveillance by an individual or group towards another person. Stalking generally refers to harassing or threatening behavior that an individual engages in repeatedly, such as following a person, appearing at a person’s home or place of business, making harassing phone calls, leaving written messages or objects, or vandalizing a person’s property. These actions may or may not be accompanied by a credible threat of serious harm, and they may or may not be precursors to an assault or murder.

_

Voyeurism:

Voyeurism is the sexual interest in or practice of spying on people engaged in intimate behaviors, such as undressing, sexual activity, or other actions usually considered to be of a private nature. A male voyeur is commonly labelled as Peeping Tom. Research found that voyeurism is the most common sexual law-breaking behavior in both clinical and general populations. Non-consensual voyeurism is considered to be a form of sexual abuse. When the interest in a particular subject is obsessive, the behavior may be described as stalking.

_

Sexual misconduct:

Sexual misconduct is a non-legal term used informally to describe a broad range of behaviors, which may or may not involve harassment. For example, some companies prohibit sexual relationships between co-workers, or between an employee and their boss, even if the relationship is consensual. Sexual misconduct is an umbrella term for any misconduct of a sexual nature that is of lesser offense than felony sexual assault (such as rape and molestation), particularly where the situation is normally non-sexual and therefore unusual for sexual behavior, or where there is some aspect of personal power or authority that makes sexual behavior inappropriate. A common theme, and the reason for the term “misconduct,” is that these violations occur during work or in a situation of a power imbalance.

_

Sexual harassment (vide infra):

Sexual Harassment includes behavior such as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other conduct of a sexual nature. It is conduct that affects a person’s employment or education or interferes with a person’s work or educational performance or creates an environment that a reasonable person would find it intimidating, hostile or offensive. Reasonable person standard is a standard established to establish whether or not a particular act or conduct constitutes sexual harassment. The basis of the standard is what a “reasonable person” would conclude regarding the act rather than focusing on the specific victim or perpetrator.

Sexual harassment includes:

-an unwelcome sexual advance

-an unwelcome request for sexual favours

-engaging in other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that is offensive, humiliating or intimidating.

Examples of sexual harassment include staring or leering, unwelcome touching, suggestive comments, taunts, insults or jokes, displaying pornographic images, sending sexually explicit emails or text messages, and repeated sexual or romantic requests. It also includes behaviours that may be considered criminal offences, such as sexual assault, stalking or indecent exposure.

_

Retaliation:

Action taken by an accused individual or by a third party against any person because that person has opposed sexual harassment or because that person has filed a complaint, testified, assisted or participated in any manner in sexual harassment investigation or proceeding. This includes action taken against a bystander who intervened to stop or attempt to stop sexual harassment or sexual misconduct.

_

Locker room talk:

As for “locker room talk,” experts say it’s not usually a crime, but it can feed into a culture of sexual harassment. In some situations, “locker room talk” could actually be seen as a form of sexual harassment. Inappropriate jokes or pinup pictures in the workforce can create a hostile work environment, which could fall under the umbrella of sexual harassment.

______

What is the difference between sexual harassment and sexual assault?

Some authors have either confused the terms sexual assault and sexual harassment, or they have relegated sexual harassment to a back seat issue very different from sexual assault. Many believe that within the continuum of harm, sexual harassment eventually might lead to sexual assault. Both include unwelcome sexual advances to include touching. While there is overlap between the definitions, this overlap doesn’t constitute conflict. The real distinction between sexual harassment and sexual assault is sexual harassment’s connection to the victim’s employment and/or work performance, which is why sexual harassment is a civil rights issue. However, in some contexts, sexual harassment may constitute a crime under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Sexual assault is a crime against another person. However, unlike sexual harassment, it has nothing to do with their employment and/or work performance; it is a criminal assault of a sexual nature against another person. Sexual harassment is a broad term, including many types of unwelcome verbal and physical sexual attention. Sexual assault refers to sexual contact or behavior, often physical, that occurs without the consent of the victim. Sexual harassment generally violates civil laws—you have a right to work or learn without being harassed—but in many cases is not a criminal act, while sexual assault usually refers to acts that are criminal. In dealing with both matters, our focus should not be to emphasize one over the other. Rather, we need to recognize their relationship, how poor command climate fosters sexual harassment which can prevent bystanders from intervening and can embolden predators. In the response side of the equation, it is important to recognize the very real possibility that a victim may in fact have been subjected to both sexual harassment and sexual assault by the time a report is made.

_______

_______

Introduction to sexual harassment:

You’re not an A-list Hollywood actor, nor a mover and shaker in political circles. You’re just someone – probably a woman – with a job. And while they may not be powerful or important anywhere else, someone – a customer, a colleague, probably a man – is sexually harassing you at work. Maybe you’re a temping teaching assistant in a school, and the French teacher announces to a class full of teenage boys anyone can get a good look up your skirt – a comment none of them will ever let you forget. Said man then drunkenly tells you at the school Christmas party that he’d like to “rub one out against your leg”. Or maybe you’re a waitress in a wine bar, facing down a group of customers who think bits of your arse come free with the drinks, and who have not stopped trying to cop a feel of your tits all night. Maybe you’re the ambitious young lawyer working on mergers and acquisitions who finds herself the subject of a hilarious “joke” at an office function – one that involves being questioned on your sex life with your husband and having your boobs grabbed by the boss, both in front of the whole department. It’s humiliating, it’s reductive, and – inconceivably, to those who have not been in that situation – it’s an experience that provokes its victims, rather than its perpetrators, to feel guilt, anger, remorse and shame. And as gross and upsetting leers, inappropriate comments and touching up can be, it can get worse. So much worse. And become a consistent pattern. But when you’re in precarious work, or young, marginalised or just completely dependent on the income from your job, often harassment incidents that are illegal are endured by workers terrified of what will happen to their income if they take action.

_

One of the consequences of the increasing integration of men and women in the workplace has been the increased opportunity for conflict based upon gender differences (Browne, 2006). Despite the inclusion of gender as a banned ground of discrimination in the Human Rights Act 2003, and the best efforts of legislators and employers, gender-based conflict has become a major issue for organisations, and a topic of interest in research (Colarelli & Haaland, 2002). It appears that the differences between the sexes assert themselves in organisational settings, with the outcome that men and women are not just simply interchangeable employees (Browne, 2006). One of the most prevalent forms of this conflict has been labelled sexual harassment (Colarelli & Haaland, 2002). Although a myriad of definitions exist, there is no universal agreement on an objective definition of sexual harassment (Golden, Johnson & Lopez, 2001).

_

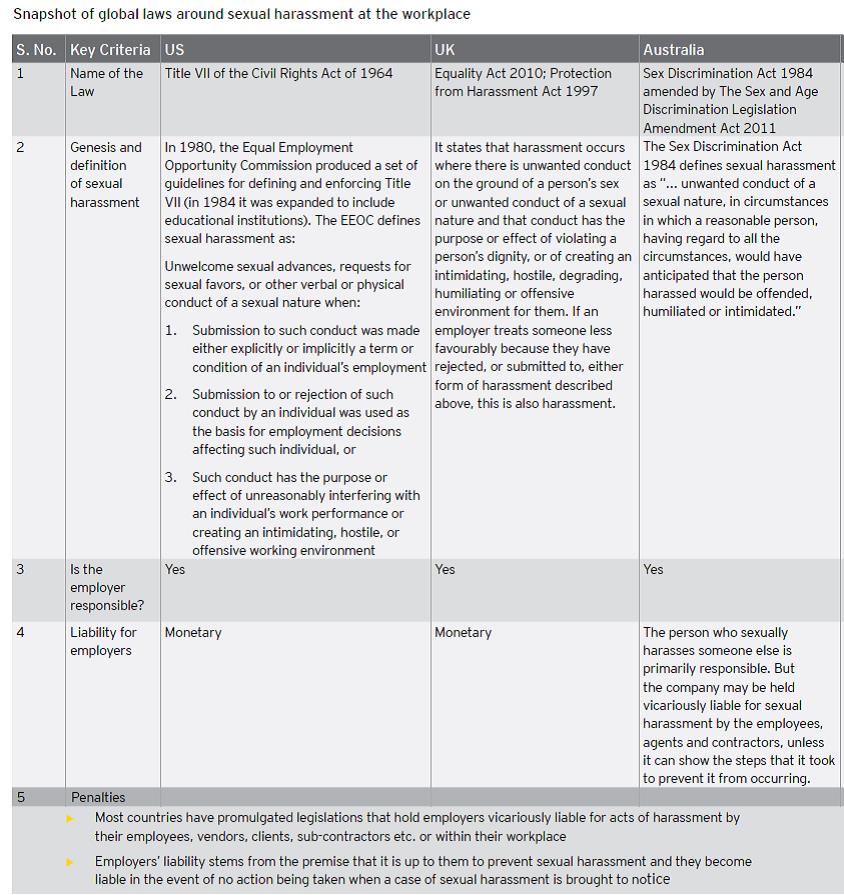

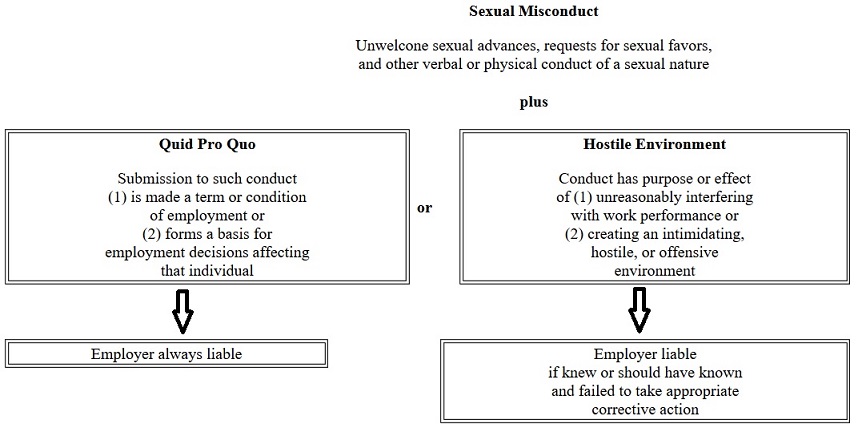

Sexual harassment is a kind of sex discrimination that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act 1964 in the United States. According to Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC), sexual harassment occurs whenever there is an unwanted conduct on the basis of gender and which consequently affects an individual’s job. The legal definition of sexual harassment is “unwelcome verbal, visual, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is severe or pervasive and affects working conditions and a hostile work environment. Sexual harassment refers to “unwanted sexual advances, whether touches, looks, pressures to have sex or even jokes” (Henslin & Nelson, 1996 p.300). Such behavior is imposed sometimes as a condition on a person’s employment. There are two types of sexual harassment. The first one known as ‘quid pro quo’, means ‘something for something’ consists of harassment that has a direct impact on the individual’s job. Suppose a manager imposes on his subordinate to get sexually cooperative, or else he or she will be fired from the job. The second one is known as hostile environment. It results from unwanted behaviors and conducts from seniors and other personnel on the job, such as discussing sexual topics, make use of inappropriate words such as ‘babe’ demonstrate indecent gestures and use crude and unusual language. Over few decades the American Supreme Court has declared sexual harassment as a reason of action under Title VII, sexual harassment still prevails in workplaces. Most complaints come from women. However, number of complaints filed by men is rising. There is an ever-increasing number of men reporting against female supervisors. According to EEOC, in 2007, 16% cases were reported by men. A Government study in UK stated that 2 out of 5 sexual victims are male.

_

It is not about fun but abuse of authority. It is found that only 5% to 15% of harassed women report problems of sexual harassment. There are various reasons why victims are hesitant to make accuses of sexual harassment. They may fear to lose their or interrupt their career or they may even not be believed. They can also think that nothing will be done to cease the harassment and to help them. Likewise, men are also reluctant to report cases, because of their masculine stereotype. They may think that this can have a negative impression on their masculinity. However, there appears to be a short of consensus regarding the definition of sexual harassment, especially when investigating the behaviors and the conditions in which sexual harassment occurs (Bimrose, 2004; Fitzgerald and Ormerod, 1991; Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Stockdale and Hope, 1997). There is no single and precise definition of sexual harassment, either in terms of behavior or the circumstances in which it occurs (Bimrose, 2004; Fitzgerald and Ormerod, 1991; Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Stockdale and Hope, 1997).

_

Sexual harassment is seen as one of the most difficult and emotional issue that employers, employees and human resource professionals are facing today. In fact no profession or occupation is exempted from this problem. Sexual harassment goes far beyond one’s social background, educational level, age group or ethnic belonging. It touches all the layers of the population without any exception (Kim and Kleiner, 1999). Sexual harassment has been called “an endemic feature of the contemporary workplace” (Jackson and Newman, 2004). Willness et al. (2007) find that sexual harassment results in the victim’s decreased job satisfaction, resignation from work, less socialization, bad health and some symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder for persons, as well as lower productivity, mounted absenteeism and rising sick leave costs for organizations. To know whether unwanted behavior is pervasive enough to create unfriendly environment, factors such as frequency of discriminatory manner, harshness of the behavior, was it physically threatening or only offensive statement, must be considered. Sexual harassment must be considered as an issue to be discussed in organizations, before improving a person’s skills to prevent sexual harassment.

_

It is complicated to recognize unfriendly and unwelcome environment. The fact must determine whether circumstances have crossed the line. Courts have declared that men and women do not have the same level of sensitivity. Two-thirds of men will be happy if they are approached sexually at work, and others will not like it, states a study. Causes of sexual harassment can be very complexed. Close relationships at work, having same interests, employees depending upon each other for teamwork are reasons that bring closeness and can step over professional limits and mislead people to cross the line. Factors such as personal problems may also give rise to sexual harassment. No job is distinct from sexual harassment.

In 2009 after a study at the University of Minnesota, it was found that women who occupy supervisory positions are most prone to sexual harassment. Researchers have found that most victims are women on supervisory positions. This strongly shows that sexual harassment is not only about sexual desire but also about to have power over and dominance. Nowadays men retain supervisory position and they decide if a report against sexual harassment lodged by a woman will be taken into consideration or not. As it is, women are considered to be less productive than men in organizations and it is necessary for the former to work, others tend to profit from such situations. So as not to lose their jobs, some women accept to be treated as such.

Sexual harassment may be a warning sign of life traumas such as divorce or death of spouse or even the child. It affects the victims professionally, academically, financially and socially. Even organizations suffer from low productivity, loss of staff, absenteeism and legal costs if the matter is taken into court. Cruel sexual harassment can have the same psychological effect as rape or sexual physical attack. Some victims, especially women may try to attempt suicide as well.

_

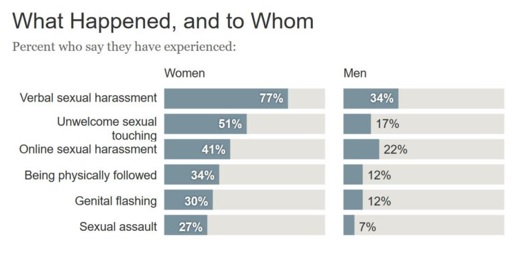

We should care because of the human and organizational costs of sexual harassment. Research tells us that victims perceive sexual harassment as annoying, offensive, upsetting, embarrassing, stressful, and frightening. Sexual harassment often results in emotional and physical stress and stress-related mental and physical illnesses. Research in the United States links sexual harassment to increased absenteeism, job turnover, transfer requests, and decreases in work motivation and productivity. Sexual harassers may be supervisors, peers, customers, or clients. Although men sometimes experience sexual harassment (mostly young men, gay men, members of ethnic or racial minorities, and men working in female-dominated work groups), the vast majority of those who experience it are women. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the United States estimates that between 25 and 50 percent of women have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. When women are minorities, either statistically because there are few of them or because they are ethnic minorities, they are often at increased risk for sexual harassment.

_

Employers may be legally accountable for sexual harassment against employees and they may be liable to pay for damages. A victim of sexual harassment must report to an official. The victim must participate in investigation and cooperate fully. The matter must be kept confidential as reputation will be at stake. Both the complainant and the accused will have a chance to defend their cases. The law protects employees who cooperate in administrative complaints, thus one must not be afraid to collaborate. The person concerned must be able to answer questions such as name of harasser, where and when the incident occurred, when investigation is being carried out. The plaintiff has full rights to know everything about the investigation. The complainant must admit that the problem exists and have the courage to talk about it and say what is wrong. The victim must not blame himself/herself for some else’s behavior. He/she must not ignore hostile behavior and must not try to handle the situation alone. He/she must get help. Policies need to be adopted to prevent sexual harassment, such as: sexual harassment policy, general harassment policy. Managers must ensure that such situations do not occur at workplace. Employees need to be informed and addressed on such matters. They must be aware of the law that protects them. Independent bodies must take the responsibility to make regular checks in organizations so as to question staff and ensure that everything is going on well with their work.

_

Not all workplace or educational conduct that may be described as “harassment” affects the terms, conditions or privileges of employment or education. For example, a mere utterance of an isolated ethnic, gender-based or racial epithet which creates offensive feelings in an employee or student, while highly inappropriate, would not normally affect the terms and conditions of their employment or limits a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from the University’s educational programs or activities.

A common myth is that sexual harassment is just a few notches down from sexual assault but it’s not that simple. Sexual harassment is uniquely tied to power structures, often in employment and career advancement situations. The perpetrator holds the key to moving onwards and upwards, creating a dilemma for the victim: submit and be exploited or resist and be punished. The victim is placed in an intimidating lose-lose situation without any power or control. Therefore, sexual harassment can and does run the gamut from demeaning comments to requests for sexual favors to unwanted sexual advances. In addition, it doesn’t always but certainly can include sexual assault, which is any non-consensual or coerced sexual act, including sexual touching.

Harassment is also different than unwanted sexual attention, which consists of unwelcome come-ons and comments that are not primarily designed to demean and intimidate. Think terrible pick-up lines: “I lost my teddy bear, will you sleep with me instead?” from a guy at the bar is unwanted sexual attention, but from your boss, its sexual harassment.

To be clear, it’s not only women as victims and men as perpetrators, even though that setup is the vast majority of cases. Of the 13,000 charges of sexual assault logged in 2016 by the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (believed to be just the tip of the iceberg), 83 percent of them were filed by women. And the women who face sexual harassment by bosses and supervisors aren’t just rising Hollywood starlets or, like Anita Hill, Yale-educated lawyers. They’re everyday people—restaurant workers, clerks, flight attendants, students, health care workers, programmers—whose bosses control scheduling, raises, future promotions, and references.

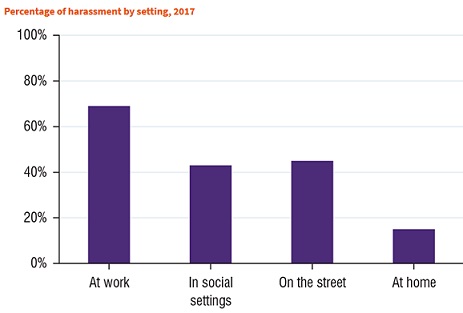

_

Sexual harassment in the workplace is unwelcome or unwanted attention of a sexual nature from someone at work that causes discomfort, humiliation, offence or distress, and/or interferes with the job. This includes all such actions and practices of a sexual nature by a person or a group of people directed at one or more workers. The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, a supervisor in another area, a co-worker, or a client or customer. Harassers or victims can be of either gender. In most modern legal contexts, sexual harassment is illegal. Laws surrounding sexual harassment generally do not prohibit simple teasing, offhand comments, or minor isolated incidents—that is due to the fact that they do not impose a “general civility code”. In the workplace, harassment may be considered illegal when it is frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment or when it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim’s demotion, firing or quitting). The legal and social understanding of sexual harassment, however, varies by culture.

_

Sexually harassing behaviors differ in type and severity. Key determining factors are that the behavior is:

- Unwelcome

- Sex or gender based

- Reasonably perceived as offensive and objectionable under both a subjective and objective assessment of the conduct.

_

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission guidelines define sexual harassment as the following:

“Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment”.

Sexual harassment was first recognized in cases in which women lost their jobs because they rejected sexual overtures from their employers (e.g., Barnes v. Costle 19771). This type of sexual harassment became defined as quid pro quo sexual harassment (Latin for “this for that,” meaning that a job or educational opportunity is conditioned on some kind of sexual performance). Such coercive behavior was judged to constitute a violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Soon it was recognized in employment law that pervasive sexist behavior from coworkers can create odious conditions of employment—what became known as a hostile work environment—and also constitute illegal discrimination (Farley 1978; MacKinnon 1979; Williams v. Saxbe 19762). These two basic forms of sexual harassment, quid pro quo and hostile environment harassment, were summarized in guidelines issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 1980.

_

Sexual harassment can occur in a variety of circumstances, including but not limited to the following:

- The victim as well as the harasser may be a woman or a man. The victim does not have to be of the opposite sex.

- The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, an agent of the employer, a supervisor in another area, a co-worker, or a non-employee.

- The victim does not have to be the person harassed but could be anyone affected by the offensive conduct.

- Unlawful sexual harassment may occur without economic injury to or discharge of the victim.

- The harasser’s conduct must be unwelcome.

The defining characteristic of sexual harassment is that it is unwanted. It is important to clearly let an offender know that certain actions are unwelcome. Hostile work or educational environments can be created by behaviors such as addressing women in crude or objectifying terms, posting pornographic images in the office, and by making demeaning or derogatory statements about women, such as telling anti-female jokes. Hostile environment harassment also encompasses unwanted sexual overtures such as exposing one’s genitals, stroking and kissing someone, and pressuring a person for dates even if no quid pro quo is involved (Bundy v. Jackson 1981; Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson 1986).

An important distinction between quid pro quo and hostile environment harassment is that the former usually involves a one-on-one relationship in which the perpetrator has control of employment- or educational-related rewards or punishments over the target. In contrast, the latter can involve many perpetrators and many targets. In the hostile environment form of sexual harassment, coworkers often exhibit a pattern of hostile sexist behavior toward multiple targets over an extended period of time (Holland and Cortina 2016). For hostile sex-related or gender-related behavior to be considered illegal sexual harassment, it must be pervasive or severe enough to be judged as having had a negative impact upon the work or educational environment. Therefore, isolated or single instances of such behavior typically qualify only when they are judged to be sufficiently severe. Legal scholars and judges continue to use the two subtype definitions of quid pro quo and hostile environment to define sexual harassment.

_

When is sexually based conduct harassment?

Attraction between employees should be a private matter between the employees, so long as it does not cross the boundary between welcome conduct and harassment. To determine whether sexual conduct in the workplace amounts to sexual harassment, distinctions must be made between sexual advances that are:

- Invited: if the conduct is welcome, harassment has not occurred but could cause difficulties down the line if an office romance goes sour.

- Uninvited but welcome: again, while there is no harassment, the potential for harassment could exist if a relationship between two employees breaks up.

- Offensive but tolerated: just because an employee does not make a complaint does not mean that harassment is not occurring — if you see it or hear of it, put a stop to it.

- Flatly refused: this is clearly harassment and should be handled accordingly.

_

Is gender-based harassment the same as sexual harassment?

There are forms of harassment that are gender-based but are nonsexual in nature. Gender-based harassment is harassment that would not have occurred but for the sex of the victim. So gender based harassment is a type of sexual harassment. It lacks sexually explicit content but is directed at one sex and motivated by animus against that sex, whether female or male.

Example:

A comment like “You’re a woman, you can’t handle this job” may amount to gender-based harassment even though it does not carry a sexual connotation.

_

Who is harasser & who may be harassed?

It is commonly thought that workplace sexual harassment is limited to interactions between male bosses and female subordinates. This is not true. In fact, sexual harassment can occur between any co-workers, including the following:

- peer to peer harassment;

- subordinate harassment of a supervisor;

- men can be sexually harassed by women;

- same sex harassment – men can harass men; women can harass women;

- third party harassment; and

- offenders can be supervisors, co-workers, or non-employees, such as customers, vendors, and suppliers.

Another common perception is that the person who is the recipient of the behavior is the victim of the sexual harassment. In fact, anyone who is affected by the offensive conduct, whether they were the intended “target” or not, is a victim of sexual harassment. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) states, ”the victim does not have to be the person harassed but could be anyone affected by the offensive conduct.” Likewise, there is no “typical harassed woman.” Women of all ages, backgrounds, races and experience and in every work environment experience sexual harassment.

_

Is Sexual Harassment about Sex or Power?

According to a 1992 study conducted by the International Labor Organization (ILO),”Sexual harassment is inextricably linked with power and takes place in societies which often treat women as sex objects and second-class citizens.” Catharine MacKinnon, one of the foremost writers on the topic, describes sexual harassment as an “explosive combining of unacceptable sexual behavior and the abuse of power.” A particular incident of harassment may or may not include any explicitly sexual behavior, but it always involves some form of abuse of power. For example, when a harasser sabotages a woman’s work, he is not engaging in any kind of romantic sexual action. He is engaging in aggression. This situation is no different from that of the street harasser who comments on a woman’s body as she walks by, the co-worker who won’t stop touching her or the landlord who won’t repair the sink because she hasn’t been “nice enough” to him. While not one of these actions is “sexual” in an affectionate or friendly sense, all are forms of sexual harassment.

It is very important to closely examine the “sexual” aspect of sexual harassment, because sexuality is often used as a justification for this social practice. Confusion about the difference between sexual invitation and sexual harassment is common. Many men and women around the world believe that sexual harassment is a practice based on simple sexual attraction. It is often seen as an expression of male interest and a form of flattering sexual attention for women – a sometimes vulgar but essentially harmless romantic game, well within the range of normal, acceptable behavior between men and women. However, the difference between invitation and harassment is the use of power. Harassment is not a form of courtship and it is not meant to appeal to women. It is designed to coerce women, not to attract them. When the recipient of sexual harassment has no choice in the encounter, or has reason to fear the repercussions if she declines, the interaction has moved out of the realm of invitation and courtship into the arena of intimidation and aggression. Confusion about the dynamics of sexuality and power in sexual harassment prevents women from reacting to harassers with strong, effective countermeasures.

_

Can one incident of harassment or offensive behavior constitute sexual harassment?

It depends. Quid pro quo cases may be considered sexual harassment when linked to the granting or denial of employment benefits. On the other hand, the conduct would have to be quite severe for a single incident or isolated incidents of offensive sexual conduct or remarks to rise to the level of a hostile environment. Hostile environment claims usually require proof of a pattern of offensive conduct. Nevertheless, a single and extremely severe incident of harassment may be sufficient to constitute a Title VII violation. A general rule of thumb is that the more severe the harassment is, the less likely it is that the victim will be required to show a repetitive series of incidents. This is especially true when the harassment is physical.

_

Situations:

Sexual harassment may occur in a variety of circumstances—in workplaces as varied as factories, school, college, acting, and the music business. Often, the perpetrator is in a position of power or authority over the victim (due to differences in age, or social, political, educational or employment relationships). They can also be expecting to receive such power or authority in form of promotion.

Forms of harassment relationships include:

- The perpetrator can be anyone, such as a client, a co-worker, a parent or legal guardian, relative, a teacher or professor, a student, a friend, or a stranger.

- The place of harassment occurrence may vary from different schools workplace and other.

- There may or may not be other witnesses or attendances.

- The perpetrator may be completely unaware that his or her behavior is offensive or constitutes sexual harassment. The perpetrator may be completely unaware that his or her actions could be unlawful.

- The incident can take place in situations in which the harassed person may not be aware of or understand what is happening.

- The incident may be a one-time occurrence but more often the incident repeats.

- Adverse effects on the target are common in the form of stress, social withdrawal, sleep, eating difficulties, and overall health impairment.

- The victim and perpetrator can be any gender.

- The perpetrator does not have to be of the opposite sex.

- The incident can result from a situation in which the perpetrator thinks they are making themselves clear, but is not understood the way they intended. The misunderstanding can either be reasonable or unreasonable. An example of unreasonable is when a woman holds a certain stereotypical view of a man such that she did not understand the man’s explicit message to stop.

With the advent of the internet, social interactions, including sexual harassment, increasingly occur online, for example in video games or in chat rooms. According to the 2014 PEW research statistics on online harassment, 25% of women and 13% of men between the ages of 18 and 24 have experienced sexual harassment while online.

_

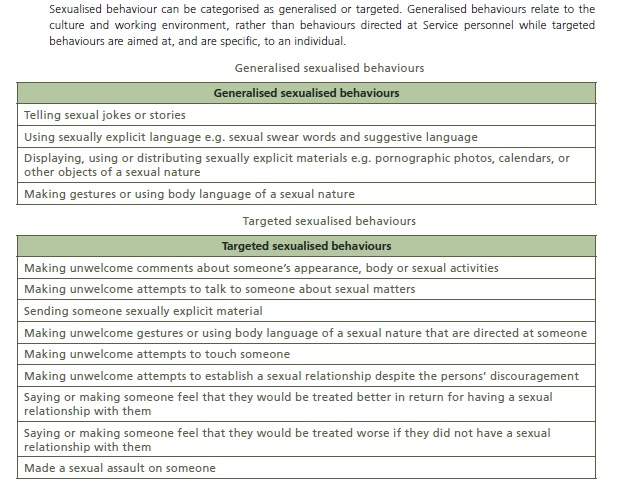

Generalised versus targeted sexual behaviour:

______

______

Etymology and history of sexual harassment:

The modern legal understanding of sexual harassment was first developed in the 1970s, although related concepts have existed in many cultures. The activists, Lin Farley, Susan Meyer, and Karen Sauvigne went on to form the Working Women’s Institute which, along with the Alliance Against Sexual Coercion (founded in 1976 by Freada Klein, Lynn Wehrli, and Elizabeth Cohn-Stuntz), were among the pioneer organizations to bring sexual harassment to public attention in the late 1970s. One of the first legal formulations of the concept of sexual harassment as consistent with sex discrimination and therefore prohibited behavior under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 appeared in the 1979 seminal book by Catharine MacKinnon entitled “Sexual Harassment of Working Women”. Although Catharine MacKinnon is sometimes credited with creating the laws surrounding sexual harassment in the United States, the first known use of the term sexual harassment was in a 1973 report about discrimination called “Saturn’s Rings” by Mary Rowe, Ph.D. though Rowe has stated that sexual harassment was being discussed in women’s groups in Massachusetts in the early 1970s, and wasn’t likely the first person to use the term. At the time, Rowe was the Chancellor for Women and Work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Due to her efforts at MIT, the university was one of the first large organizations in the U.S. to develop specific policies and procedures aimed at stopping sexual harassment. In the book In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution (1999), journalist Susan Brownmiller quotes Cornell University activists who believed they had coined the term ‘sexual harassment’ in 1975 after being asked for help by Carmita Wood, a 44-year-old single mother who was being harassed by a faculty member at Cornell’s Department of Nuclear Physics.

_

‘Sexual Harassment of Working Women’ by Catharine A. MacKinnon:

Noted legal scholar and feminist Catherine MacKinnon defined sexual harassment as “the unwanted imposition of sexual requirement in the context of a relationship of unequal power”. Sexual harassment of working women has been widely practiced and systematically ignored. Men’s control over women’s jobs has often made coerced sexual relations the price of women’s material survival. Considered trivial or personal, or natural and inevitable, sexual harassment has become a social institution. MacKinnon offers here the first major attempt to understand sexual harassment as a pervasive social problem and to present a legal argument that it is discrimination based on sex. Beginning with an analysis of victims’ experiences, she then examines sex discrimination doctrine as a whole, both for its potential in prohibiting sexual harassment and for its limitations. Two distinct approaches to sex discrimination are seen to animate the law: one based on an analysis of the differences between the sexes, the other upon women’s social inequality. Arguing that sexual harassment at work is sex discrimination under both approaches, she criticizes the effectiveness of the law in reaching the real determinants of women’s social status. She concludes that a recognition of sexual harassment as illegal would support women’s economic equality and sexual self-determination at a point where the two are linked.

_

Historical antecedents of sexual harassment:

Ancient Rome:

In ancient Rome, according to Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, what is now called sexual harassment was then any of accosting, stalking, and abducting. Accosting was “harassment through attempted seduction” or “assaulting another’s chastity with smooth talk … contrary to good morals”, which was more than the lesser offense(s) of “obscene speech, dirty jokes, and the like”, “foul language”, and “clamor”, with the accosting of “respectable young girls” who however were dressed in slaves’ clothing being a lesser offense and the accosting of “women … dressed as prostitutes” being an even lesser offense. Stalking was “silently, persistently pursuing” if it was “contrary to good morals”, because a pursuer’s “ceaseless presence virtually ensures appreciable disrepute”. Abducting an attendant, who was someone who follows someone else as a companion and could be a slave, was “successfully forcing or persuading the attendant to leave the side of the intended target”, but abducting while the woman “has not been wearing respectable clothing” was a lesser offense.

_____

_____

Definitions of sexual harassment:

Despite both national and international efforts to eliminate sexual harassment, there is no single definition of what constitutes prohibited behavior. Generally, international instruments define sexual harassment broadly as a form of violence against women and as discriminatory treatment, while national laws focus more closely on the illegal conduct. All definitions, however, are in agreement that the prohibited behavior is unwanted and causes harm to the victim.

-At the International level, the United Nations General Recommendation 19 to the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women defines sexual harassment as including: Such unwelcome sexually determined behavior as physical contact and advances, sexually colored remarks, showing pornography and sexual demands, whether by words or actions. Such conduct can be humiliating and may constitute a health and safety problem; it is discriminatory when the woman has reasonable ground to believe that her objection would disadvantage her in connection with her employment, including recruitment or promotion, or when it creates a hostile working environment.

-The International Labor Organization (ILO) is a specialized United Nations agency that has addressed sexual harassment as a prohibited form of sex discrimination under the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention (No. C111). The ILO has made clear that sexual harassment is more than a problem of safety and health, and unacceptable working conditions, but is also a form of violence (primarily against women).

-At the regional level, both the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe (COE) address sexual harassment as illegal behavior. The European Commission of the EU defines sexual harassment as: Unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, or other conduct based on sex affecting the dignity of women and men at work. This includes unwelcome physical, verbal or nonverbal conduct. Unlike other international definitions of sexual harassment, the European Commission also distinguishes three types of harassment: physical, verbal, and nonverbal sexual harassment and states that there is a range of unacceptable behavior: Conduct is considered sexual harassment if it is (1) unwanted, improper or offensive; (2) if the victim’s refusal or acceptance of the behavior influences decisions concerning her employment or (3) the conduct creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating working environment for the recipient.

Some examples of physical, verbal and non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature are found in the European Commission’s guide:

- Physical conduct of a sexual nature – ‘unwanted physical contact ranging from unnecessary touching, patting or pinching or brushing against another employee’s body, to assault and coercing sexual intercourse’;

- Verbal conduct of a sexual nature – ‘unwelcome sexual advances, propositions or pressure for sexual activity; continued suggestions for social activity outside the workplace after it has been made clear that such suggestions are unwelcome; offensive flirtations; suggestive remarks, innuendoes or lewd comments’;

- Non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature – ‘the display of pornographic or sexually suggestive pictures, objects or written materials; leering, whistling, or making sexually suggestive gestures’.

Finally, definitions of sexual harassment found at the international and regional level form the international laws that prohibit sexual harassment.

_

At the national level, the United Sates was one of the first countries to define sexual harassment, as a prohibited form of sex discrimination that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, a federal law. The U.S. government body that enforces the Civil Rights Act, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), defines sexual harassment as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature,” when

- submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment;

- submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting such individual; or

- such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile or offensive working environment.

(1) and (2) are called “quid pro quo”(Latin for “this for that” or “something for something”). They are essentially “sexual bribery”, or promising of benefits, and “sexual coercion”. Type (3) known as “hostile work environment”, is by far the most common form. This form is less clear cut and is more subjective.

In addition to national definitions of sexual harassment, most states in the U.S. also prohibit sexual harassment, through state laws that may differ slightly from the federal definition.

Unwelcome Behavior is the critical word. Unwelcome does not mean “involuntary.” A victim may consent or agree to certain conduct and actively participate in it even though it is offensive and objectionable. Therefore, sexual conduct is unwelcome whenever the person subjected to it considers it unwelcome. Whether the person in fact welcomed a request for a date, sex-oriented comment, or joke depends on all the circumstances.

_______

One of the leading cases on sexual harassment, Janzen v. Platy Enterprises Ltd., identifies three key elements in its description of sexual harassment in the workplace. They are:

- Conduct of a sexual nature which is gender based,

- Conduct that is unwelcome, and

- Conduct that detrimentally affects the work environment or leads to adverse job- related consequences.

Note, while women typically experience sexual harassment more often than men, sexual harassment can and does happen to men. It can also occur between two people of the same sex.

_

- What is Conduct of a Sexual Nature which is Gender Based?

“Gender based” refers to behaviour that relates specifically to gender. In other words, the offensive behaviour references gender (e.g. overt sexual solicitation) or the behaviour occurs because of the gender (e.g. an offensive joke does not refer to sex, but the joke is played to embarrass the person because she is a woman).

“Conduct of a sexual nature” includes a wide range of behaviours or actions. Some examples defined by the courts include:

- Physical conduct such as:

Pinching, grabbing, patting, rubbing, sexual assault (which is also a criminal matter), sexual intercourse, unnecessary physical contact, kissing. In other words, any kind of touching that has a sexual connotation.

- Verbal conduct such as:

Making derogatory comments about a person’s appearance or body including insulting comments and gestures, insulting nicknames, verbal abuse or threats, unwelcome remarks, jokes, innuendoes or taunting. Also, comments about a person’s or colleague’s personal life including inviting a colleague out when it’s clear the person doesn’t want to socialize with you, making sexual propositions, spreading false rumours about a person’s sex-life or morals, referring to sexual affairs with previous employees, questions regarding sex life.

- Environmental examples such as:

The display of pornographic or other offensive pictures, making practical jokes that cause awkwardness or embarrassment, crude, sexual or abusive remarks, making suggestive comments, innuendoes, and sexual jokes.

What about generally accepted banter or normal social interaction at work?

If other employees are not offended by crude comments, sexual innuendo, posters on the wall, or other “generally accepted banter” in the workplace, this doesn’t render your complaint or concern invalid. It may however, require that you express an objection to the behaviour so as to let others know that you are offended. If you’ve previously participated in the banter, it may be more difficult, to show that the conduct was unwelcome. If all parties were involved in the banter, there is a need for a specific objection since consensual conversations about sex are not prohibited in the workplace.

- What do you mean by “unwelcome” in nature?

Courts use an objective test for determining if conduct is unwelcome. The test asks what a reasonable person would consider to be unwelcome, and assumes that one can only be expected to refrain from engaging in conduct which he or she could reasonably have known was unwelcome. An express objection on the part of the victim to certain more overt behaviours such as rubbing, pinching, grabbing and patting, while prudent, is not likely required to show its unwelcome nature because a reasonable person ought to know these actions are unacceptable and unwelcome. However, if someone flirts with the idea of dating a colleague and asks them out on a date, a reasonable person would not likely perceive this to be harassment so an express objection may be required. If the pursuit persists and turns into a pattern of behaviour that demoralizes, humiliates and or impedes an otherwise healthy working relationship, a reasonable person ought to know their actions are unwelcome. If behaviour is not self-evidently offensive an express objection may be required as a ‘reasonable person’ may not be aware their behaviour is unwelcome.

- What do you mean by “detrimentally affecting the work environment?

Sexual harassment is any sexually-oriented practice that endangers an individual’s continued employment, negatively affects his/her work performance, or undermines their sense of personal dignity.

_____

Indian definition of sexual harassment:

Sexual harassment in India is termed “Eve teasing” and is described as: unwelcome sexual gesture or behaviour whether directly or indirectly as sexually coloured remarks; physical contact and advances; showing pornography; a demand or request for sexual favours; any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct being sexual in nature or passing sexually offensive and unacceptable remarks. The critical factor is the unwelcomeness of the behaviour, thereby making the impact of such actions on the recipient more relevant rather than intent of the perpetrator.

______

______

Forms and kinds of sexual harassment:

_

Sexual harassment can take many forms. Sexual harassment:

- may include, but is not limited to sexual advances or request for sexual favors, inappropriate comments, jokes or gestures, or other unwanted verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.

- may be blatant and intentional and involve an overt action, a threat of reprisal, or may be subtle and indirect, with a coercive aspect that is unstated.

- does not have to include intent to harm, be directed at a specific target, or involve repeated incidents.

- may be committed by anyone, regardless of gender, age, position, or authority. While there is often a power differential between two persons, perhaps due to differences in age, social, educational, or employment relationships, harassment can occur in any context.

- may be committed by a stranger, an acquaintance, or someone with whom the complainant has an intimate or sexual relationship.

- may be committed by or against an individual or may be a result of the actions of an organization or group.

- may occur by or against an individual of any sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation.

- may occur in the classroom, in the workplace, in residential settings, over electronic media (including the internet, telephone, and text), or in any other setting.

- may be a one-time event or part of a pattern of behavior.

- may be committed in the presence of others or when the parties are alone.

- may affect the complainant (person experiencing the conduct) and/or third parties who witness or observe the harassment.

_

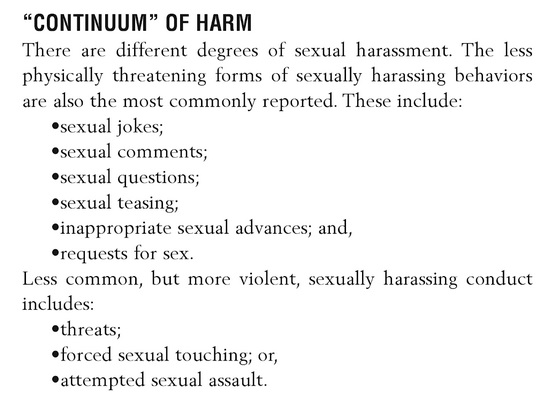

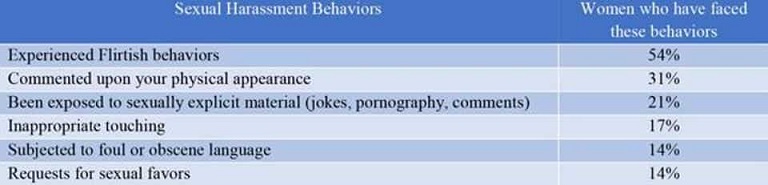

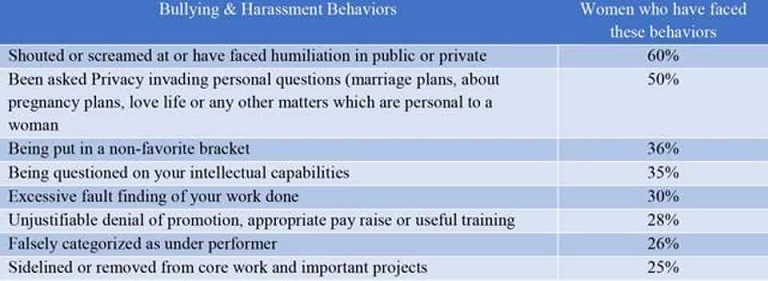

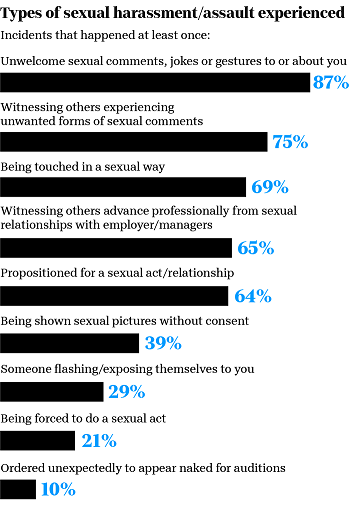

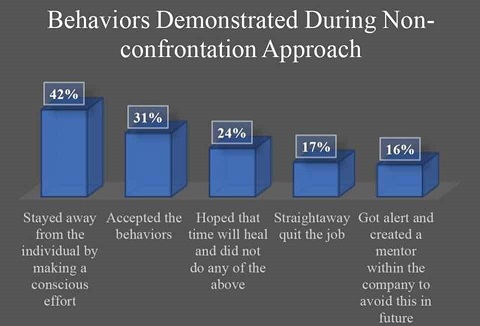

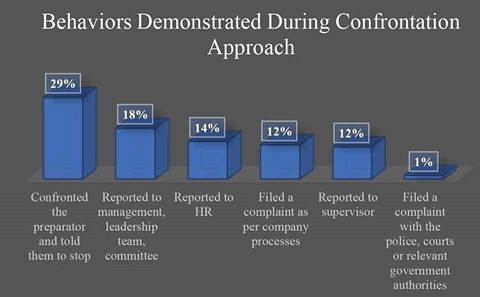

A study found different sexually harassing experiences as seen in the figure below:

_

_

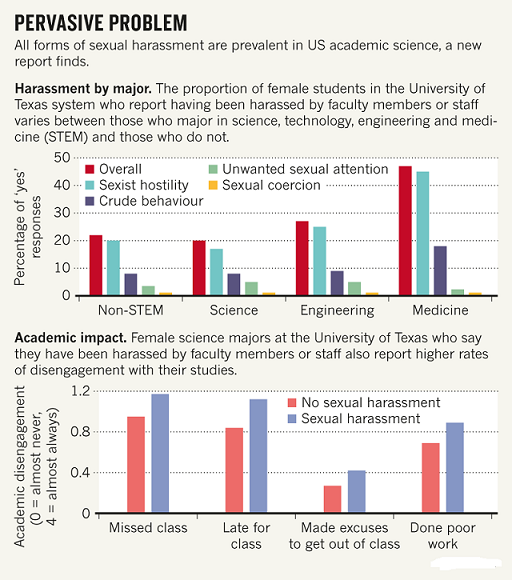

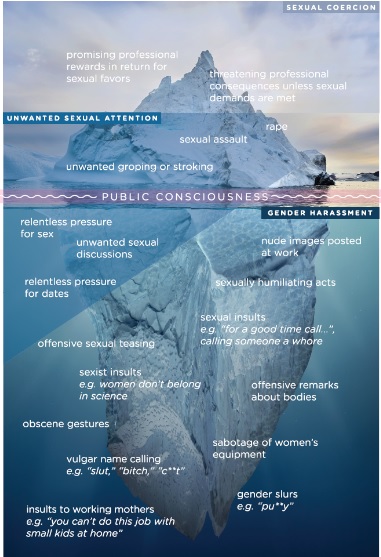

Figure below shows different degrees of sexual harassment:

__

Various forms of sexual harassment:

- Physical Sexual Harassment:

Physical sexual harassment is the most obvious and well-known form of sexual harassment. It is exercised through unwelcome touching such as rubbing up against a person or physically interfering with another’s movements or preventing another from completing their work.

- Verbal Sexual Harassment:

Remarks or comments that are disrespectful insults or slurs may also be considered as verbal harassment towards an individual.

- Visual Sexual Harassment:

At first glance “visual harassment” by definition may seem obvious in that one individual is exposing themselves to another individual who does not appreciate the exposure. However, visual harassment comes in other forms that are not as blatant as perhaps a fellow employee exposing themselves. Visual harassment can be demonstrated through cartoons, drawings, photos or video clips that are considered offensive and or insulting to the victim.

_

Sexual harassment occurs in a variety of situations that share a commonality: the inappropriate and unwelcome introduction of sexual content or attention in a situation where sex should be irrelevant. Sexual harassment is distinguished from normal friendly social interactions by the introduction of elements of coercion, threat, intimidation, or insult. Sexual harassment does not refer to occasional compliments of a socially acceptable nature; it refers to behavior that is offensive, that lowers morale, and that interferes with the work or education of its recipients. Behaviour that is based on mutual attraction, friendship and respect is not sexual harassment. Sexual harassment does not refer to friendships or mentoring relationships that enhance the educational/employment environment; it refers to behavior that adversely affects the educational/employment environment. Sexual harassment includes sexual advances or demeaning verbal behaviors that are repeated and unwanted, even where they are exclusively verbal and not coercive. Sexual harassment can occur even when the victim suffers no tangible job detriment.

Generally, a single sexual joke, offensive epithet, or request for a date does not constitute sexual harassment; however, being repeatedly subjected to such jokes, epithets, or requests day after day despite having voiced objections may be sexual harassment. Coercive behavior, including suggestions that academic or employment reprisals or rewards will follow the refusal or granting of sexual favors, constitutes gross misconduct; a single incident may be grounds for dismissal as an employee or as a student.

Examples of Sexual Harassment:

Sexual harassment may occur between individuals of different sexes or of the same sex provided that the harassment is directed at the recipient because of his/her gender. Sexual harassment may occur between individuals in a hierarchical relationship (e.g., between supervisor and employee or between faculty member and students) or between peers (e.g., between co-workers or students.) It may be caused by “outside parties”; i.e., vendors, patrons, service persons, or other individuals who are not members of the company or university community but who come in contact with faculty, staff or students in the employment/educational environment. Also, the complainant does not have to be the person who is harassed, but may be anyone adversely affected by the offensive conduct. Examples of indirect, third-party harassment include conversations about sex in the hearing range of others to whom such conversations are unwelcome.

Sexual harassment can be verbal, nonverbal, or physical. Severe acts such as unwelcome sexual grabbing may be judged harassing based on a single act while less offensive actions may constitute harassment if repeated and/or pervasive. Listed below are examples of behavior that in the employment or educational environment could constitute sexual harassment.

Verbal:

- Sexual innuendoes or other sexually suggestive comments

- Sexually explicit questions, jokes or anecdotes

- Sexual slurs

- Graphic comments about an individual’s clothing, body or sexual activities

- E-mail circulation or sexual materials or harassing messages

- Graffiti

- Repeated unsolicited propositions for dates and/or sexual intercourse

- Initiating and/or spreading rumors about a person’s sex life

- Sexually suggestive or insulting sounds

Nonverbal:

- Lewd gestures

- Indecent exposure

- Display of sexually suggestive objects or pictures in the workplace or classroom without a job-related or educational purpose

Physical:

- Patting, pinching or intentional brushing against the body in a sexual manner

- Impeding or blocking movement

- Invading a person’s body space, standing closer than appropriate or necessary for the work or activity being done

- Attempted or actual kissing or sexual touching

- Physical assault, coerced sexual intercourse, rape or attempted rape

The preceding examples are indicative of behavior that may constitute sexual harassment, or be considered part of a pattern of sexual harassment. They are not intended to be exhaustive and are used as illustrations only. Courts have also held that sexual harassment can occur even when the victim suffers no tangible job detriment and the University is not informed of the problem. Whether a particular act or course of conduct constitutes sexual harassment depends on a review of all the circumstances, including frequency, location and severity of the conduct, i.e., whether the conduct is physically threatening or humiliating as opposed to merely an offensive utterance and whether it unreasonably interferes with a person’s employment environment, educational environment, or environment for participation in a University activity. A victim is not necessarily required to object directly to the offending person in order to be deemed to be offended by it.

_

Groping:

This is a tricky term that dominates headlines, encompassing allegations against President Trump, actor Dustin Hoffman, Sen. Al Franken and talent agent Adam Venit. The definition of groping can vary depending on state law but is mainly categorized as unlawful touching. Alemzadeh notes that there’s no single official legal definition, just that it falls under the context of assault. For example, in Illinois, where she practices, groping would fall under criminal sex abuse rather than assault because Illinois law requires penetration to file assault charges. Groping rarely gets prosecuted despite its rampant occurrence because most people categorize it and dismiss it as bad behavior instead of reporting it. David Cobbins, who’s part of a team at USC that trains U.S. Army leaders on how to prevent sexual assault and harassment, says that the body part being groped shouldn’t have bearing in terms of being reported as long as it’s unwanted.

_

Grooming:

Typically, a predator will use their position within their community or industry to gain trust and ensure that the control they wield as the adult in the relationship means the ensuing abuse will remain secret. Most of the allegations against Roy Moore, for example, depict a man who first established himself as a reliable, trustworthy individual to the parent of a girl he then sexually pursued.

_

Catcalling:

Most women, particularly those living in or around big cities, have had the experience of being ‘catcalled’ – having someone loudly comment on your sexual attractiveness. The comments can range from the relatively benign (“Hello gorgeous!”) to threats of sexual assault. In recent years, however, commentators and feminists have been paying growing attention to catcalling, arguing that it represents an unacceptable assertion of power by men in public over the bodies of women. Others, however, argue that it’s just a bit of fun. The latest research from YouGov shows that, according to a large majority of the public, it is never appropriate (72%) to catcall. 18% say that it’s sometimes appropriate, while 2% think that it’s always appropriate. Men (22%) were only marginally more likely than women (18%) to say that it is ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ appropriate. Asked whether catcalls are compliments or not, most Americans (55%) say that they constitution harassment, 24% aren’t sure while only 20% think that they are ‘compliments’.

Bystander Sexism in the Intergroup Context: The Impact of Cat-calls on Women’s reactions towards Men, a 2010 study:

Authors examine the intergroup reactions experienced by 114 female students at a U.S. university in New England who imagined being a bystander to a sexist cat-call remark or control greeting. Results indicate that women experienced greater negative intergroup emotions and motivations towards the outgroup of men after overhearing the cat-call remark. Further, the experience of group-based anger mediated the relationship between the effect of study condition on the motivation to move against, or oppose, men. Results indicate that bystanders can be affected by sexism and highlights how the collective groups of men and women can be implicated in individual instances of sexism.

_

Obscene phone call: