Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

ATHEISM

ATHEISM:

_____

Caveat:

This article has no desire to insult anybody in any way at all. If anyone feels offended, it is a regrettable misunderstanding because the criticisms are aimed at the objectives of the belief, never at believers as individuals. I recognize and respect right of all individuals to believe in their faith and their God if that helps them to live better life in the brief period of human existence allotted to them. But religious beliefs and doctrines become dangerous if they threaten the liberty and the integrity of the individual or of the society.

_____

_____

Prologue:

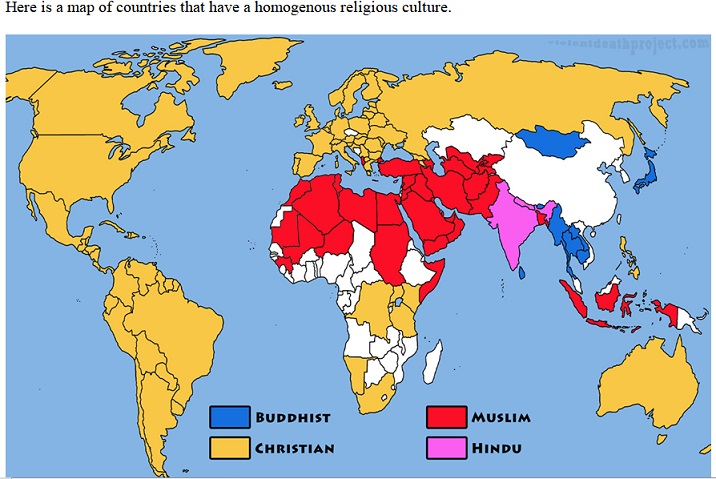

According to Psalm 14 of the Bible, people who don’t believe in God are filthy, corrupt fools, entirely incapable of doing any good. Before the 18th century, the existence of God was so accepted in the western world that even the possibility of true atheism was questioned. This is called theistic innatism—the notion that all people believe in God from birth; within this view was the connotation that atheists are simply in denial. Former American president George Herbert Walker Bush said that atheists are neither citizens or nor patriots as America is one nation under God. There is no position on which people are so immovable as their religious beliefs. The seminal social thinkers of the nineteenth century — Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud — all believed that religion would gradually fade in importance and cease to be significant with the advent of industrial society. The dazzling achievements of medicine, engineering, and mathematics as well as the material products generated by the rise of modern capitalism, technology, and manufacturing industry during the 19th century emphasized and reinforced the idea of mankind’s control of nature. Personal catastrophes, contagious diseases, disastrous floods, and international wars, once attributed to supernatural forces, primitive magic, and divine intervention, or to blind fate, came to be regarded as the outcome of predictable and preventable causes. Despite all these, the world today, with some exceptions, is as furiously religious as it ever was, and in some places more so than ever.

Atheists and theists too often seem more intent on scoring points at one another’s expense than carefully following where the evidence leads them. Many of the loudest voices in the debate about God refuse to accept the possibility that anyone who disagrees with them deserves to be taken seriously, and one must see the evidence contrary of one’s belief. All five of the core arguments for a supernatural God (mystery, creation, design, revelation, and morality) extensively violate basic rules of rationality. “Your God is too small for my universe,” Carl Sagan once reacted to a Christian theologian. According to the scientist and thinker Lawrence Krauss, within a tiny circle between your thumb and forefinger against a dark sky, and with a powerful telescope, you could see at least 100,000 galaxies, each containing more than 400 billion stars. You may also witness at least three supernovae in a given night. Over the course of the history of the Milky Way, our galaxy, about 200 million stars have exploded, says Krauss. Our sun will explode within six billion years and of course the earth will disappear along with the sun and it is doubtful whether the humans, their culture, religion and God would survive till that day to see the disappearance of the sun. The incompatibility of reason and faith has been a self-evident feature of human cognition and public discourse for centuries. Ask yourself, which is more moral, helping the poor out of concern for their suffering, or doing so because you think the creator of the universe wants you to do it, will reward you for doing it or will punish you for not doing it?

______

______

Some quotations about Atheism and Atheists:

Evil men do evil on their own accord. For good men to do evil requires religion.

-H.L. Mencken

_

Our belief is not a belief. Our principles are not a faith. We do not rely solely upon science and reason, because these are necessary rather than sufficient factors, but we distrust anything that contradicts science or outrages reason. We may differ on many things, but what we respect is free inquiry, open-mindedness, and the pursuit of ideas for their own sake.

-Christopher Hitchens

_

I’ve been worshipping the sun for a number of reasons. First of all, unlike some other gods I could mention, I can see the sun. It’s there for me every day, and the things it brings me are quite apparent all the time: heat, light, food, reflections at the park—the occasional skin cancer, but hey! There’s no mystery, no one asks for money, I don’t have to dress up, and there’s no boring pageantry.

-George Carlin

_

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

-Epicurus

_

Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful.

-Edward Gibbon

_

I prefer ‘rationalism’ to ‘atheism.’ The word ‘atheist,’ meaning ‘no God,’ is negative and defeatist. It says what you don’t believe and puts you in an eternal position of defence. ‘Rationalism’ on the other hand states what you do believe; that is, that which can be understood in the light of reason. The question of God and other mystical objects-of-faith are outside reason and therefore play no part in rationalism and you don’t have to waste your time in either attacking or defending that which you rule out of your philosophy altogether.

-Isaac Asimov

_

Given that we know that atheists are often among the most intelligent and scientifically literate people in any society, it seems important to deflate the myths that prevent them from playing a larger role in our national discourse.

-Sam Harris

_

Atheism is more than just the knowledge that Gods do not exist, and that religion is either a mistake or a fraud. Atheism is an attitude, a frame of mind that looks at the world objectively, fearlessly, always trying to understand all things as a part of nature.

-Emmett F. Fields

_

All thinking men are atheists.

-Ernest Hemingway

_

Those who kneel to God are learning how to prostrate themselves before a king.

-Joseph Joubert

_

Faith means not wanting to know what is true.

-Nietzsche

_

Religion is excellent stuff for keeping common people quiet. Religion is what keeps the poor from murdering the rich.

-Napoleon Bonaparte

_____

_____

Terminology:

- A priori –Knowledge, judgments, and principles which are true without verification or testing. It is universally true.

- Agnosticism–The belief that the existence of God is not knowable. The word is derived from the negative ‘a’ combined with the Greek word ‘gnosis,’ which means knowledge. Hence, agnosticism is the belief that God cannot be known.

- Atheism–The lack of belief in a god and/or the belief that there is no god. The position held by a person or persons that ‘lack belief’ in god(s) and/or deny that god(s) exist.

- Causality–The relationship between cause and effect. The principle that all events have sufficient causes.

- Chance–Being undetermined. Events without apparent cause. An accidental happening.

- Choice–Action based on one’s volition, will, desire.

- Cosmological argument–An attempt to prove that God exists by appealing to the principle that all things have causes. There cannot be an infinite regress of causes; therefore, there must be an uncaused cause: God.

- Cosmology–Study of the origin and structure of the universe.

- Deduction–A system of logic, inference, and conclusion drawn from examination of facts. Conclusions drawn from the general down to the specific.

- Deism–The belief that there is a God, but that God is not involved in the world. Deism denies any revelatory work of God in the world whether it be by miracles or by scripture.

- Deontology–The study of moral obligation.

- Determinism–The teaching that every event in the universe is caused and controlled by natural law.

- Dialectic–The practice of examining ideas and beliefs using reason and logic. It is often accomplished by question and answer.

- Dogma–A generally held set of formulated beliefs.

- Empiricism–The proposition that the only source of true knowledge is experience. Search for knowledge through experiment and observation. Denial that knowledge can be obtained a priori.

- Epistemology–The branch of philosophy that deals with knowing and the methods of obtaining knowledge.

- Ethics–Study of right and wrong, good and bad, moral judgment, etc.

- Faith–Acceptance of ideals, beliefs, etc., which are not necessarily demonstrable through experimentation or reason.

- Free will–Freedom of self-determination and action independent of external causes.

- Freethinker–A person who forms his opinions about religion and God without regard to revelation, scripture, tradition, or experience.

- God–Deity, infinite being of power, influence, knowledge, and immortality.

- Humanism–The system of philosophy based upon human reason, actions, and motives without concern of deity or supernatural phenomena.

- Induction–A system of logic where specific facts are used to draw a general conclusion.

- Infidel–A person who does not believe in any particular religious system.

- Karma–In Hinduism, the total compilation of all a person’s past lives and actions that result in the present condition of that person.

- Metaphysics–Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that explores the nature of being, existence, and reality.

- Monotheism–The belief that there is only one God in the universe.

- Morals–Ethics, the codes, values, principles, and customs of a person or society.

- Myth–Something not true, fiction, or falsehood. A truth disguised and distorted.

- Ontological argument–An attempt at proving the existence of God by stating that God exists because our conception of Him exists, and nothing greater than God can be conceived of.

- Ontology–The study of the nature of being, reality, and substance, branch of metaphysics

- Panentheism–The belief that God is in the universe. It differs with pantheism which states that God is the universe and all that it comprises.

- Pantheism–The belief that God is the universe and all that comprises it: laws, motion, matter, energy, consciousness, life, etc. It denies that God is a person and is self-aware.

- Philosophy–The study of seeking knowledge and wisdom in understanding the nature of the universe, man, ethics, art, love, purpose, etc.

- Polytheism–The belief that there are many gods in existence in the universe.

- Pragmatism–A method in philosophy where value is determined by practical results.

- Rationalism–A branch of philosophy where truth is determined by reason.

- Relativism–The view that truth is relative and not absolute. It varies from people to people, time to time.

- Religion–Generally a belief in a deity and practice of worship, action, and/or thought related to that deity. Loosely, any specific system of code of ethics, values, and belief.

- Science–The process of learning by which theories are offered, tests developed, and experiments are conducted in order to verify and/or modify the theory.

- Teleological argument–An attempted proof of God’s existence based upon the premise that the universe is designed and therefore needs a designer: God.

- Teleology–The study of final causes, results. Having a definite purpose, goal, or design.

- Theism–The belief that there is a God, and that He is knowable and involved in the world.

- Theology–The study of things pertaining to God and/or the relation of God to the world.

- Transcendent–That which is beyond our senses and experience. Existing apart from matter.

_______

_______

God, religion and irreligion:

Many descriptions and definitions have been applied to religion (Banister, 2011), with belief in a supernatural being or beings often posited as the core feature (Burke, 1996; Norenzayan, 2010). Defining the religious and nonreligious is not necessarily straightforward. Some religious people believe in the existence of a God and also participate in religious practices, such as attending services in a place of worship. On the other hand, other people believe in the existence of a God without belonging to a particular faith or participating in religious services (Hunsberger & Altemeyer, 2006). In terms of the nonreligious, an agnostic is defined as someone who is uncertain or undecided about the existence of a God, while an atheist doesn’t believe any form of supreme being or universal force exists (Zuckerman, 2009).

_

God:

Atheism is the view that there is no God. Unless otherwise noted, this article will use the term “God” to describe the divine entity that is a central tenet of the major monotheistic religious traditions–Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. At a minimum, this being is usually understood as having all power, all knowledge, and being infinitely good or morally perfect. It must not be forgotten that social, cultural, and traditional factors can exercise a significant influence on the image of the God that is adopted by a particular era.

_

Consider the following four responses to a request for a definition of the term “God”:

God1 = the universe itself (all that exists). [Or, alternatively, God1 = love.]

God2 = the powerful being who created the universe.

God3 = the omnipotent creator of the universe whose highest goal regarding humans is that they believe that he has a son who died for them so that they might obtain salvation.

God4 = ? (No definition is possible; the word is indefinable.)

Now suppose there were a philosopher who examined these four responses. When asked the question “does God exist?” he might very well respond as follows:

In the case of God1, yes, God definitely exists, for it is obvious that the universe [or love] exists. In the case of God2, I understand the question but have no answer to it since the evidence is insufficient. In the case of God3, there is good evidence that such a being does not exist, for most humans do not believe in his son, etc., yet, if such a being were to exist, then probably he would have done things to cause them to have the given belief. And in the case of God4, I do not understand the question. Since no definition of “God4” has been given, the sentence “God4 exists” expresses no proposition whatever.

Given this response, we should say of such a philosopher that he is a theist relative to God1, an agnostic relative to God2, an atheist relative to God3, and a noncognitivist relative to God4. These answers to the four “does God exist?” questions are reasonable, though they are not necessarily the correct (or “best”) answers. It should be noted that the term “theist” is here being taken in a broad sense, one which includes what are often referred to as “deists” and “pantheists.” In a narrower sense, a theist only affirms the existence of a certain type of deity (a personal deity who rules the universe).

_____

Theism:

Theism at its most basic, is the belief in one or more gods. More modern definitions of theism suggest that the deity or deities in question must in some way impact the universe, separating theism from deism, which holds a god exists as the prime mover, but does not bother tampering with the world, if it even were able. The belief in god(s) can be broken into a host of subsections depending on the number and the kind of the gods being postulated. In monotheism, only one God exists. There are no other gods in the world. Most monotheists, however, tend to hold some technically untenable positions about beings like Satan or concepts like the Trinity. Monotheism can further be divided into personal transcendent gods, and impersonal or non-transcendent gods. In a polytheistic religion, several gods are worshiped as part of that religion. The pantheon of deities in such religions tend to specialise, in contrast with the ubiquitous gods of monotheistic religions. Most of human’s culture’s religions are polytheistic in nature, from various Native American religions, to the Classical Greeks, ancient Celtic religions, to the early Israelites. Zoroastrians hold a belief in two complementary deities or, analogously to Christianity, two complementary aspects of a single deity. Many pagan and neo-pagan religions subscribed or subscribe to some form of polytheism. Pagan means person holding religious beliefs other than those of the main world religions.

There seems to be an assumption that a theist must necessarily be a member of an organised religion with a prescribed dogma. Many of the pros/cons commonly attributed to being a theist are nothing to do with personal belief:

Pros:

-Social cohesion/sense of belonging to a group, especially in a predominantly theist culture

-Availability of the religion as a support network

-Freedom from discrimination/persecution/torture/death; depending on the prevailing local culture

Cons:

-Need to subsume personal morals to an externally demanded framework (or at least appear to)

-Time spent in religious observance that could instead be spent with your family, on altruistic goals or on personal improvement

-Expectation that gifting to charity be along religious lines, vs. any true assessment of effectiveness

_____

Deism:

Deism is a philosophical belief that posits that God exists and is ultimately responsible for the creation of the universe, but does not interfere directly with the created world. Equivalently, Deism can also be defined as the view which posits God’s existence as the cause of all things, and admits its perfection (and usually the existence of natural law and Providence) but rejects divine revelation or direct intervention of God in the universe by miracles. It also rejects revelation as a source of religious knowledge and asserts that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator or absolute principle of the universe.

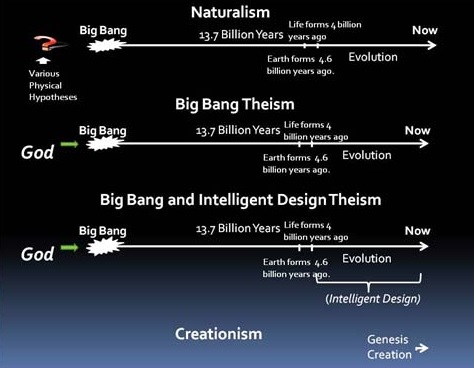

Deism is a belief that God created the universe, but left everything else to its own devices. Some views differ in specifics. Many deists believe that the Big Bang was initiated by a God (of their choice), and that everything that happened since is the consequence of scientific laws “created” at the same time. In other cases, deism implies that said God set in motion all the events needed to make life on Earth inevitable — and thus is still responsible. They may or may not believe in an afterlife. Deistic beliefs tend to differ from usual religion by the fact that the creator god is either not worthy of worship, or worship is completely unnecessary. This gives deism a greater overlap with atheism and freethought compared to religion.

____

What is the difference between deism and theism?

Deism is the belief in a creator, who made the world but does not take a personal interest in it — doesn’t require worship, answer prayers, judge behavior, or necessarily promise a life after death (unless that was part of the original creation). Deism is a fairly benign belief, because there are no consequences for accepting or rejecting it.

Theism is the belief in an active, interventionist god who not only created the world (and some believe fine-tuned it for human use), but also may require worship, answer prayers, judge sinners, and may have created a divine son or other entities to live among humans. Most theists are 100 percent certain their god(s) exist, and have faith in this without any objective, verifiable evidence. There are many theistic religions, each of which insists it is the only true one.

_____

The Simplicity of Religion:

All religions have three central properties.

(1) All religions are social systems,

(2) All endorse (and even require) something that is supernatural, and

(3) All designate something as holy or sacred.

_

A common adage is that religion provides easy answers to hard questions. The core aspect of the religious worldview is always trivial – God created the world, and the order within it. From this foundation, we get the pillars of religion: God is omnipotent, and omniscient, and interacts with humans in a direct way. Building on this premise, the basics of religious beliefs are similarly easy to comprehend – the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Five Pillars of Islam, the concepts of karma and reincarnation. There is room for the theologians to argue the finer details, but these limited foundations are all that is necessary for one to participate fully in the religion, and expect to attain its promises. Religions are inherently populist. The sociological view of religion meshes it with culture to the point of indistinguishably, and this standpoint explains the evolving nature of religions and their attendant cultures. It also allows religion to be understood in the context of a complete, cultural standpoint – for the masses, religion answers the basic philosophical questions of life while also providing the appeal to divinity that justifies their feelings of cultural superiority. The key element of any religion, more so than even a conception of divinity, is thus accessibility. Religion, as with the cultures around it, evolves by the action of the majority, and thus always reflects the requirements of the majority. It follows that those who reject religion are the same as those who are capable of levelling philosophical criticism towards their culture and society, as all are on the same plane.

The persistence of religion in the majority of the world can best be explained by the sociological view established i.e. religion is an extension and modifier of culture. As with cultural norms, religious beliefs are indefensible from any rigorous standpoint, and their extreme resistance to logical challenges closely parallels the survival of cultural identities. Once more, those with the faculty to leave strong religious traditions are likely to be the same persons who undertake criticism of cultural norms. This leaves the majority, who subscribe to both and question neither, stranded in the intellectually and morally restricting paradigm of their local religion. For these reasons, anti-theism tends to fail, unless the anti-theists are interacting with people who already hold a privileged, nuanced viewpoint of the world.

Due to the symbiosis with culture, religious moral systems and restrictions inevitably reflect the cultural standards they evolved with. A crucial problem is that, due the absolutist claims of religions, they may not ‘keep up’ with cultural changes. Reactionary movements in all societies are almost universally rooted in religious support. Passive, and occasionally violent, rejections of human rights and gender equality on “ethical” grounds are invariably backed by conservative religious attitudes. Philosophically, religion alters one’s view of the world. In the process of providing absolute answers, religion prohibits believers from readily and seriously considering foreign solutions to the original questions. In addition, religious belief ties them to a superficial understanding of their own religion and its historical impact and evolution. A believer’s worldview inevitably contains an inescapable bias in favor of their religion and its associated persons and cultures, depriving them of a great deal of nuance. For this reason, an irreligious person will always be able to craft a more accurate perspective on the world, provided religious bias is not replaced with a similar bias.

All these discussions lead back to a fundamental question about whether religion is essentially a culture — or where the line between the two is drawn. There’s definitely some interplay between the two. But culture is always evolving. If you look at secular societies like the United States, the way it was in the 1950s is very different from the way it is now. It’s moved a lot, culturally. But religion freezes culture in time. Religion dogmatizes culture and arrests its evolution although religion helps to create and reinforce culture.

Atheists retain some cultural elements of the religion. Richard Dawkins the famous atheist has described himself as a cultural Christian. He even says he prefers singing the religious Christmas carols like “Silent Night” to the others, like “Jingle Bells” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” I think all atheists should be able to enjoy some of these rituals without the burden of belief. All religions have in common that they are faith based. People are taught to believe claims from some ancient text or self-proclaimed spiritual leader, instead of relying on their own senses, evidence and critical thinking. Indeed, as Christopher Hitchens said: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”

_

Heredity can control our behavior in only the most general of ways, it cannot dictate precise behaviors appropriate for infinitely varied circumstances. In our world, heredity needs help. In the world of a fruit fly, by contrast, the problems to be solved are few in number and highly predictable in nature. Consequently, a fruit fly’s brain is largely “hard-wired” by heredity. That is to say, most behaviors result from environmental activation of nerve circuits which are formed automatically by the time of emergence of the adult fly. This is an extreme example of what is called instinctual behavior. Each behavior is coded for by a gene or genes which predispose the nervous system to develop certain types of circuits and not others, and where it is all but impossible to act contrary to the genetically predetermined script.

The world of a mammal – say a fox – is much more complex and unpredictable than that of the fruit fly. Consequently, the fox is born with only a portion of its neuronal circuitry hard-wired. Many of its neurons remain “plastic” throughout life. That is, they may or may not hook up with each other in functional circuits, depending upon environmental circumstances. Learned behavior is behavior which results from activation of these environmentally conditioned circuits. Learning allows the individual mammal to learn – by trial and error – greater numbers of adaptive behaviors than could be transmitted by heredity. A fox would be wall-to-wall genes if all its behaviors were specified genetically. With the evolution of humans, however, environmental complexity increased out of all proportion to the genetic and neuronal changes distinguishing us from our simian ancestors. This partly was due to the fact that our species evolved in a geologic period of great climatic flux – the Ice Ages – and partly was due to the fact that our behaviors themselves began to change our environment. The changed environment in turn created new problems to be solved. Their solutions further changed the environment, and so on. Thus, the discovery of fire led to the burning of trees and forests, which led to destruction of local water supplies and watersheds, which led to the development of architecture with which to build aqueducts, which led to laws concerning water-rights, which led to international strife, and on and on.

Given such complexity, even the ability to learn new behaviors is, by itself, inadequate. If trial and error were the only means, most people would die of old age before they would succeed in rediscovering fire or reinventing the wheel. As a substitute for instinct and to increase the efficiency of learning, mankind developed culture. The ability to teach – as well as to learn – evolved, and trial-and-error learning became a method of last resort. By transmission of culture – passing on the sum total of the learned behaviors common to a population – we can do what Darwinian genetic selection would not allow: we can inherit acquired characteristics. The wheel once having been invented, its manufacture and use can be passed down through the generations. Culture can adapt to change much faster than genes can, and this provides for finely tuned responses to environmental disturbances and upheavals. By means of cultural transmission, those behaviors which have proven useful in the past can be taught quickly to the young, so that adaptation to life – say on the Greenland ice cap – can be assured. Even so, cultural transmission tends to be rigid: it took over one hundred thousand years to advance to chipping both sides of the hand-axe! Cultural mutations, like genetic mutations are resisted – the former by cultural conservatism, the latter by natural selection. But changes do creep in faster than the rate of genetic change, and cultures slowly evolve. Even that cultural dinosaur known as the Catholic Church – despite its claim to be the unchanging repository of truth and “correct” behavior – has changed greatly since its beginning. Incidentally, it is at this hand-axe stage of behavioral evolution at which most of the religions of today are still stuck. Our inflexible, absolutist moral codes also are fixated at this stage.

_

What’s behind success of religion?

The historical record shows that supernatural beings have not always been associated with morality. Ancient Greek gods were not interested in people’s ethical conduct. Much like the various local deities worshiped among many modern hunter-gatherers, they cared about receiving rites and offerings but not about whether people lied to one another or cheated on their spouses. According to psychologist Ara Norenzayan, belief in morally invested gods developed as a solution to the problem of large-scale cooperation. Early societies were small enough that their members could rely on people’s reputations to decide whom to associate with. But once our ancestors turned to permanent settlements and group size increased, everyday interactions were increasingly taking place between strangers. How were people to know whom to trust? Religion provided an answer by introducing beliefs about all-knowing, all-powerful gods who punish moral transgressions. As human societies grew larger, so did the occurrence of such beliefs. And in the absence of efficient secular institutions, the fear of God was crucial for establishing and maintaining social order. In those societies, a sincere belief in a punishing supernatural watcher was the best guarantee of moral behavior, providing a public signal of compliance with social norms. Today we have other ways of policing morality, but this evolutionary heritage is still with us. Although statistics show that atheists commit fewer crimes than average, the widespread prejudice against them, as highlighted by various studies, reflects intuitions that have been forged through centuries and might be hard to overcome.

_

Religion and rule of law:

Not all beliefs are created equal, though. A recent cross-cultural study showed that those who see their gods as moralizing and punishing are more impartial and cheat less in economic transactions. In other words, if people believe that their gods always know what they are up to and are willing to punish transgressors, they will tend to behave better, and expect that others will too. Such a belief in an external source of justice, however, is not unique to religion. Trust in the rule of law, in the form of an efficient state, a fair judicial system or a reliable police force, is also a predictor of moral behavior. And indeed, when the rule of law is strong, religious belief declines, and so does distrust against atheists.

_

Reductionary accounts of religion:

Philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud have argued that God and other religious beliefs are human inventions, created to fulfil various psychological and emotional wants or needs. This is also a view of many Buddhists. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, influenced by the work of Feuerbach, argued that belief in God and religion are social functions, used by those in power to oppress the working class. According to Mikhail Bakunin, “the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory and practice.” He reversed Voltaire’s famous aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him, writing instead that “if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him.”

______

______

Irreligion:

_

Theological bar:

_

Irreligion (adjective form: non-religious or irreligious) is the absence, indifference, rejection of, or hostility towards religion. Irreligion, which may include deism, agnosticism, ignosticism, anti-religion, atheism, skepticism, ietsism, spiritual but not religious, freethought, anti-theism, apatheism, non-belief, pandeism, secular humanism, non-religious theism, pantheism and panentheism, varies in the different countries around the world.

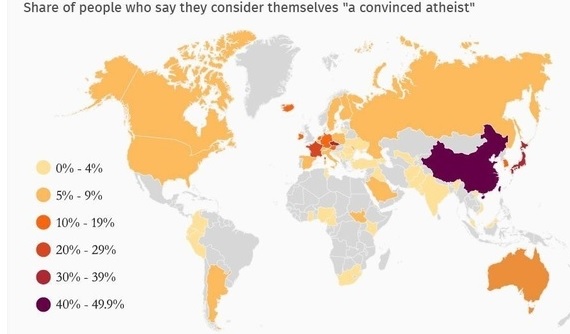

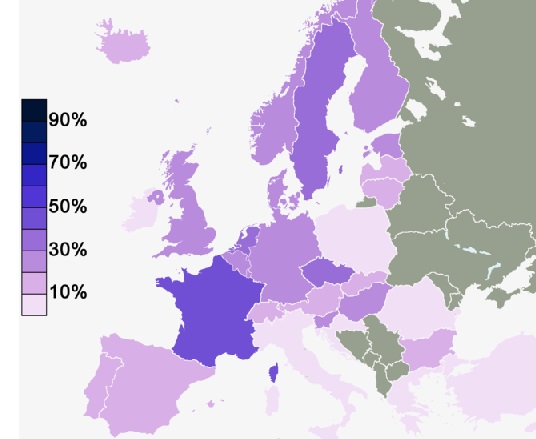

Irreligion may include some forms of theism, depending on the religious context it is defined against; for example, in 18th-century Europe, the epitome of irreligion was deism, while in contemporary East Asia the shared term meaning “irreligion” or “no religion” with which the majority of East Asian populations identify themselves, implies non-membership in one of the institutional religions (such as Buddhism and Christianity), and not necessarily non-belief in traditional folk religions collectively represented by Chinese Shendao and Japanese Shinto (both meaning “ways of gods”). According to the Pew Research Center’s 2012 global study of 230 countries and territories, 16% of the world’s population is not affiliated with a religion, while 84% are affiliated. By 2060, according to their projections, the number of unaffiliated will increase by over 35 million, but the percentage will decrease to 13% because the total population will grow faster.

_

Atheism and agnosticism:

Atheism is the absence of belief in any gods. Atheist has recognized that she or he sincerely has no belief in any god or gods. That definition covers all atheists. Note that it implies nothing about an atheist beyond lack of belief in any gods. It is not a belief system and it is not a religion. Based on the absence of any evidence for the existence of any god(s) where such evidence should be if god(s) did exist, many atheists are 99.9 percent certain that no god(s) exist. But they are open to the slight possibility they could be wrong and would be willing to accept the existence of god(s) if convincing objective, verifiable evidence were to appear. Therefore they do not have faith in the nonexistence of god(s). They simply have no belief in any gods, Atheists have always constituted a very small percentage of the population. However, the number of people who identify themselves as Atheists has grown rapidly in many countries including all predominately English speaking countries, particularly over the last few decades. This increase may have been partly caused by the decline of attendance at Sunday schools, and churches. It probably also reflects the general increase in secularism within society. Many Atheists who feel a need for spiritual discussion, fellowship in a religious community, and ritual join a congregation of the Unitarian-Universalist Association.

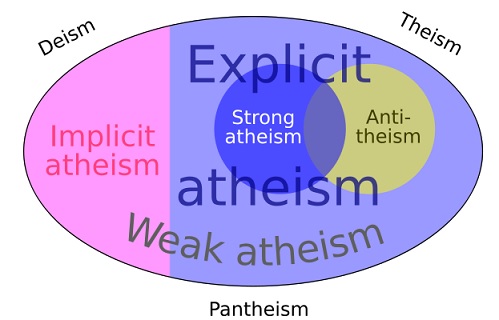

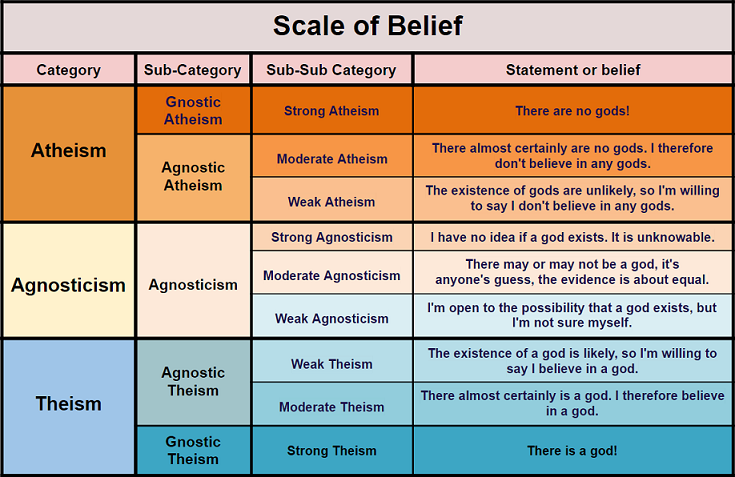

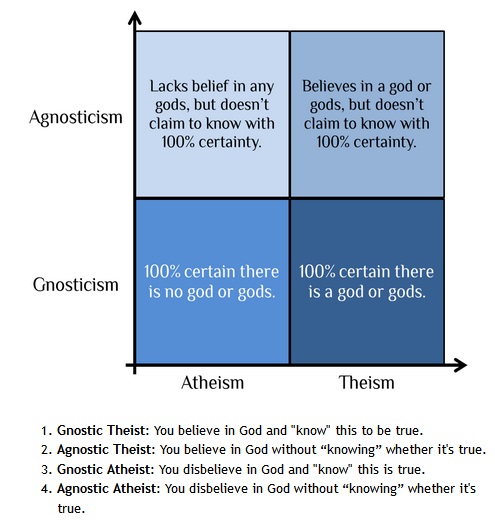

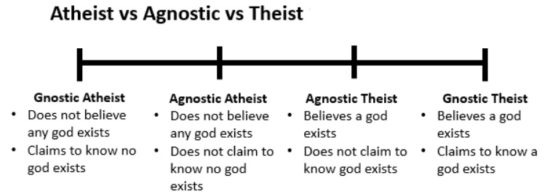

Agnosticism is not a halfway point on some continuum between atheism and theism. It is formal uncertainty about the existence or nonexistence of god(s). The agnostic asserts it is impossible to prove either the existence or the nonexistence of deities. Theists sometimes try to tell atheists that because they cannot prove god(s) don’t exist, they are agnostics. This is not true. An atheist has no belief in any god(s). That is not the same as believing it is impossible to tell if god(s) exist or not. Most atheists are agnostic atheists; they cannot prove the existence or nonexistence of any god(s) to a 100 percent certainty (agnostic), but they have no belief in any god or gods (atheist).

_

Difference between Theist and Atheist:

Theist denotes a person who believes in the existence of a God. A theist believes that God is the creator and sovereign ruler of the universe. An atheist is the one who denies the existence of any God or gods. The word Theist has been survived from Greek theos “god” (Thea) + -ist. A theist believes in the existence of a God who can be denoted as the creator and governor of the whole universe. The definition of god varies from religion to religion, person to person, and therefore no proper words have been able to characterize the actual definition of the God. However, God is generally looked as the supreme power. The description of the God is commonly found in various religions, where Gods, Goddesses, Deities, etc. are considered to contain divine powers, and thus are worshipped in various forms.

Atheist is the one who disbelieves in any Gods or supreme power. The word Atheism comes from ‘a’, meaning without, and ‘theism’ meaning belief in god or gods. Atheists do not believe that God is the creator of the Universe. Atheists believe that men are capable to live without the aid of any Gods or scriptures. The disbelief could be originated due to a deliberate choice or due to an inherent inability to believe in god. People could be atheist due to various reasons like- they are apprehensive about the insufficient evidences to believe in any religion. They might also think that religion has no associated sensible meaning, and many more. Thus, atheism may occur due to various reasons. The ideological conflicts between theists and atheists are common and often results in long debates

_____

Non-theism:

The Oxford English Dictionary (2007) does not have an entry for nontheism or non-theism, but it does have an entry for non-theist, defined as “A person who is not a theist”, and an entry for the adjectival non-theistic. Nontheism or non-theism is a range of both religious and nonreligious attitudes characterized by the absence of espoused belief in a God or gods. Nontheism has generally been used to describe apathy or silence towards the subject of God and differs from an antithetical, explicit atheism. Nontheism does not necessarily describe atheism or disbelief in God; it has been used as an umbrella term for summarizing various distinct and even mutually exclusive positions, such as agnosticism, ignosticism, ietsism, skepticism, pantheism, atheism, strong or positive atheism, implicit atheism, and apatheism. It is in use in the fields of Christian apologetics and general liberal theology.

And there are self-described atheistic Christians (e.g. Gordon Kaufman; and Paul Tillich was at least a non-theist).

There is an interesting distinction that might be made without being pedantic between “atheist” and “non-theist.” The latter is not (necessarily) one who explicitly denies the existence of God (or denies theism). A non-theist (like a non-Hegelian) may simply have never contemplated theism (or Hegel). “Atheist” suggests a person has at least given theism some thought and rejected it – or not accepted it as true or probably true. Although the difference may not be obvious, there is a difference between not believing x (i.e. not believing there is a God) and believing not-x (i.e. believing there is not a God).

______

Post-theism:

Post-theism is a variant of nontheism that proposes that the division of theism vs. atheism is obsolete, that God belongs to a stage of human development now past. Within nontheism, post-theism can be contrasted with antitheism. Though the belief system is independent from organized religions, some post-theists posit a specific religion as formerly useful. A most notable example is Frank Hugh Foster, who in a 1918 lecture announced that modern culture had arrived at a “post-theistic stage” in which humanity has taken possession of the powers of agency and creativity that had formerly been projected upon God. Another instance is Friedrich Nietzsche’s declaration that “God is dead.”

_____

Pantheism:

Pantheism is the religious belief that God is not merely omnipresent, but that God is the universe. Proponents of pantheism may point to the fact that, if you define God as something that could create the universe and create and nurture life, then you do not need to leave the natural realm to find something that fits the description perfectly; the universe itself does so. Pantheism is the view that everything is part of an all-encompassing, immanent God. All forms of reality may then be considered either modes of that Being, or identical with it. Some hold that pantheism is a non-religious philosophical position. To them, pantheism is the view that the Universe (in the sense of the totality of all existence) and God are identical (implying a denial of the personality and transcendence of God).

Richard Dawkins, in his book The God Delusion, has described Pantheism as “sexed-up atheism.” That may seem flippant, but it is accurate. Of all religious or spiritual traditions, Pantheism – the approach of Einstein, Hawking and many other scientists – is the only one that passes the muster of the world’s most militant atheist.

So what’s the difference between Atheism and Pantheism? As far as disbelief in supernatural beings, forces or realms, there is no difference. World Pantheism also shares the respect for evidence, science, and logic that’s typical of atheism. However, Pantheism goes further, and adds to atheism an embracing, positive and reverential feeling about our lives on planet Earth, our place in Nature and the wider Universe, and uses nature as our basis for dealing with stress, grief and bereavement. It’s a form of spirituality that is totally compatible with science. Indeed, since science is our best way of exploring the Universe, respect for the scientific method and fascination with the discoveries of science are an integral part of World Pantheism. Naturalistic Pantheism, of the kind espoused by the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, is similar to atheism insofar as it disbelieves in a personal God or other deities and supernatural beings, and the “god” of Spinoza is essentially just a metaphor for the laws that govern the universe. However, unlike atheists, pantheists tend look to nature and the universe for mystical or spiritual fulfilment.

_

The differences between Atheism, Pantheism, and Syntheism:

The Syntheist vocabulary constantly returns to the three terms Atheism, Pantheism, and Syntheism. Atheism is the belief that there has been no god presented to us so far which we can credibly believe in. Atheism is the opposite of theism, the belief that at least one god exists independently of human existence (often divided between monotheism claiming there is one god only as opposed to polytheism believing there are many gods). Pantheism is the belief that all dualistic theisms are based on mistaken assumptions, that there is no point in discussing God as something external to our obvious existence. According to Pantheism, The Universe and God amount to one and the same thing. God is internal and not external to The Universe and everything that exists is divine. An atheist can therefore also be a pantheist and vice versa. What Syntheism adds to this spectrum is the concept that rather than discussing whether gods exist independently of us or not (as if this for some strange reason would be a necessary condition for divinity), we have to admit that all gods have been created by humanity and nobody else, and we are consequently free to keep creating gods (even physically) as long as we admit that this is precisely what we do when we conduct religion.

__

Deism vs. Pantheism:

Richard Dawkins described the difference between these two systems of thought in his books. Deism, he suggested, is stripped-down theism, whereas pantheism is dressed-up atheism. Perhaps the main difference between them is that deists believe in an actual deity but don’t talk about him much, whereas pantheists talk about God all the time but aren’t referring to a deity when they do so.

_

Apatheism:

Apatheism (a highly original portmanteau of “apathy” and “theism”) is an attitude that the very question of whether or not deities exist is not relevant or meaningful in life. Apatheists are not even interested in addressing any claims for or against god(s). Almost literally “I don’t care about gods.” It’s not a claim, belief or belief system but an attitude. Author and journalist Jonathan Rauch quite effectively described apatheism as: A disinclination to care all that much about one’s own religion and even a stronger disinclination to care about other people’s.

____

Atheism and Satanism:

Terms like Satanism, satanic, and even the name Satan, encompass a variety of ideological, philosophical, and spiritual beliefs today. “Satanic” groups can be quite different from one another, but use the same terminology. There are different ways to classify satanic groups according to how each group believes and behaves. Not every group performs satanic rituals, participates in satanic worship, reads the The Satanic Bible, uses traditional Satanic symbols, or attends “the Church of Satan.” Satanism can mean either the belief that Satan needs to be seriously worshiped (which is actually Luciferianism) OR a philosophy of human nature and reverence for oneself, based on the teachings of Anton Szandor LaVey, founder of the church of Satan; and this philosophy involves different ritual rites, doctrines, lifestyles etc.

Atheism is the belief that no deities exist, whereas Satanism is either the belief that Satan is a deity and needs to be worshiped -call it type 1 Satanism (for whatever reason) OR the belief that Satan doesn’t exist but uses the metaphorical ideas to express a world view -call it type 2 Satanism. An atheist can be a type 2 Satanist (or vice-versa) but not a type 1 Satanist. And a type 1 Satanist is NOT an Atheist but actually a type of Theist. To keep things simple, Wikipedia defines “Theistic Satanism (also known as traditional Satanism, Spiritual Satanism or Devil worship)” to be ” a form of Satanism with the primary belief that Satan is an actual deity or force to revere or worship”. This is different from Atheistic Satanism.

____

Anti-religion:

Antireligion is opposition to religion of any kind. The term has been used to describe opposition to organized religion, religious practices or religious institutions. This term has also been used to describe opposition to specific forms of supernatural worship or practice, whether organized or not. Opposition to religion also goes beyond the misotheistic spectrum. As such it is distinct from deity-specific positions such as atheism (the denial of belief in deities) and antitheism (an opposition to belief in deities), although “antireligionists” may also be atheists or antitheists.

_

Non-religion:

Some people have a total lack of faith system, neither believing nor disbelieving in a spiritual realm but they are few and far between. The fact that these people are so rare is a matter of intense curiosity. There is strong evidence supporting the notion that there is something inherent in the human design which makes practically all people question whether or not a spiritual realm exists, if they doubt its existence at all.

_____

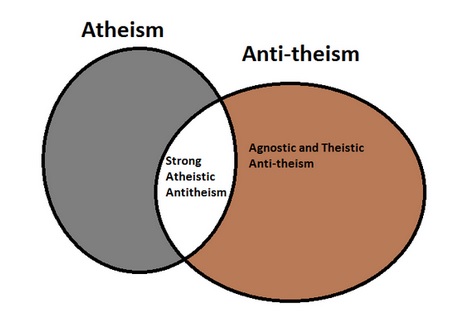

Antitheism:

Antitheism (sometimes anti-theism) is the opposition to theism. The term has had a range of applications. In secular contexts, it typically refers to direct opposition to the belief in any deity. Antitheism, also known pejoratively as “militant atheism” (despite having nothing to do with militancy) is the belief that theism and religion are harmful to society and people, and that even if theistic beliefs were true, they would be undesirable. Antitheism, which is often characterized as outspoken opposition to theism and religion, asserts that religious and especially theistic beliefs are harmful and should be discarded in favor of humanism, rationalism, science and other alternatives. Antitheism is, perhaps surprisingly, technically separate from any and all positions on the existence or non-existence of any given deity. Antitheism simply argues that a given (or all possible) human implementations of religious beliefs, metaphysically “true” or not, lead to results that are harmful and undesirable, either to the adherent, to society, or – usually – to both. As justification the antitheists will often point to the incompatibility of religion-based morality with modern humanistic values, or to the atrocities and bloodshed wrought by religion and by religious wars.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines antitheist as “One opposed to belief in the existence of a god”. The earliest citation given for this meaning dates from 1833. Antitheism has been adopted as a label by those who regard theism as dangerous, destructive, or encouraging of harmful behavior. Christopher Hitchens offers an example of this approach in Letters to a Young Contrarian (2001), in which he writes: “I’m not even an atheist so much as I am an antitheist; I not only maintain that all religions are versions of the same untruth, but I hold that the influence of churches, and the effect of religious belief, is positively harmful.”

_

Atheism vs. antitheism:

Atheism and anti-theism so often occur together at the same time and in the same person that it’s understandable if many people fail to realize that they aren’t the same. Making note of the difference is important, however, because not every atheist is anti-theistic and even those who are, aren’t anti-theistic all the time. Atheism is simply the absence of belief in gods; anti-theism is a conscious and deliberate opposition to theism. Many atheists are also anti-theists, but not all and not always.

There is a distinct difference between an atheist and an anti-theist. First of all, there are several variations of atheists. Some state they lack belief in God. By this they mean that they neither affirm nor deny God’s existence; they don’t have a position either way. There are atheists who don’t know if God exists, and there are others who doubt he does. Then there are atheists who are stronger in their denial and believe that God does not exist. Atheists generally cite lack of evidence for God’s existence and will sometimes relate, particularly in America, the behavior of the God of the Old Testament with antiquated cultures that are not relevant for today. Nevertheless, one could categorize these kinds of atheists into four main areas:

- Those who lack belief

- Those who don’t know if God exists

- Those who doubt that God exists

- Those who believe God does not exist

Anti-theist:

An anti-theist would be someone who not only believes that God does not exist but also is against the idea of God’s existence. He would oppose religion. Just as there are varieties of atheists, there are varieties of anti-theists. Some anti-theists oppose the idea of God but don’t do much about it. Then there are those who assert that any belief in God is harmful to society, and the proper thing to do is reduce harm by openly attacking and denouncing theistic beliefs with the aim of eradicating all religion. Of course, this makes no sense since they can’t demonstrate that “reducing harm” is the “right” thing to do. They just assume it is proper and act accordingly. Anti-theists, like atheists, don’t have any objective moral standard. Anyway, atheists have no belief in any god or gods (weak atheism), where anti-theists work against the idea of God’s existence (strong atheism). All anti-theists are atheists, but not all atheists are anti-theists.

_

Anti-theism and Activism:

Anti-theism requires more than either merely disbelieving in gods or even denying the existence of gods. Anti-theism requires a couple of specific and additional beliefs: first, that theism is harmful to the believer, harmful to society, harmful to politics, harmful, to culture, etc.; second, that theism can and should be countered in order to reduce the harm it causes. If a person believes these things, then they will likely be an anti-theist who works against theism by arguing that it be abandoned, promoting alternatives, or perhaps even supporting measures to suppress it.

It’s worth noting here that, however, unlikely it may be in practice, it’s possible in theory for a theist to be an anti-theist. This may sound bizarre at first, but remember that some people have argued in favor of promoting false beliefs if they are socially useful. Religious theism itself has been just such a belief, with some people arguing that because religious theism promotes morality and order it should be encouraged regardless whether it is true or not. Utility is placed above truth-value. It also happens occasionally that people make the same argument in reverse: that even though something is true, believing it is harmful or dangerous and should be discouraged. The government does this all the time with things it would rather people not know about. In theory, it’s possible for someone to believe (or even know) that but also believe that theism is harmful in some manner — for example, by causing people to fail to take responsibility for their own actions or by encouraging immoral behavior. In such a situation, the theist would also be an anti-theist. Although such a situation is incredibly unlikely to occur, it serves the purpose of underscoring the difference between atheism and anti-theism. Disbelief in gods doesn’t automatically lead to opposition to theism any more than opposition to theism needs to be based on disbelief in gods. This also helps tell us why differentiating between them is important: rational atheism cannot be based on anti-theism and rational anti-theism cannot be based on atheism. If a person wishes to be a rational atheist, they must do so on the basis of something other than simply thinking theism is harmful; if a person wishes to be a rational anti-theist, they must find a basis other than simply not believing that theism is true or reasonable. Rational atheism may be based on many things: lack of evidence from theists, arguments which prove that god-concepts are self-contradictory, the existence of evil in the world, etc. Rational atheism cannot, however, be based solely on the idea that theism is harmful because even something that’s harmful may be true. Not everything that’s true about the universe is good for us, though. Rational anti-theism may be based on a belief in one of many possible harms which theism could do; it cannot, however, be based solely on the idea that theism is false. Not all false beliefs are necessarily harmful and even those that are, aren’t necessarily worth fighting.

Religious moderation as compared to religious extremism is an example of theistic anti-theism, also known as dystheism. Dystheism also encompasses questioning the morals even of a deity you believe in, e.g. choosing to obey commandments on nonviolence over calls to violence from God, despite them both being clearly put forward by this alleged giver of all morals.

_

Modern anti-theism, be it in the form of Soviet oppression or the prolific New Atheists, has not greatly undermined religion in society. Indeed, even in the face of the internet and the globalization of information, the world has a seen a resurgence of religion, especially fundamentalist strains. Popular anti-theism seems to have little effect on the masses, despite the strength of the arguments presented. The societies which achieved mass secularization, notably those in Northern Europe, did so without revealing what combination of socio-economic factors allowed this. It could not be education, for that has failed everywhere else, nor could it be wealth, for the United States and Saudi Arabia are highly religious. The apologist’s explanation, which posits an emotional or physiological need for religion, could not be true, for the non-theistic East Asian societies have proved highly successful in the modern world.

_

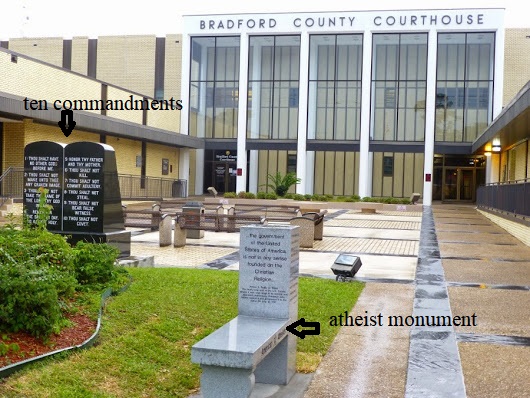

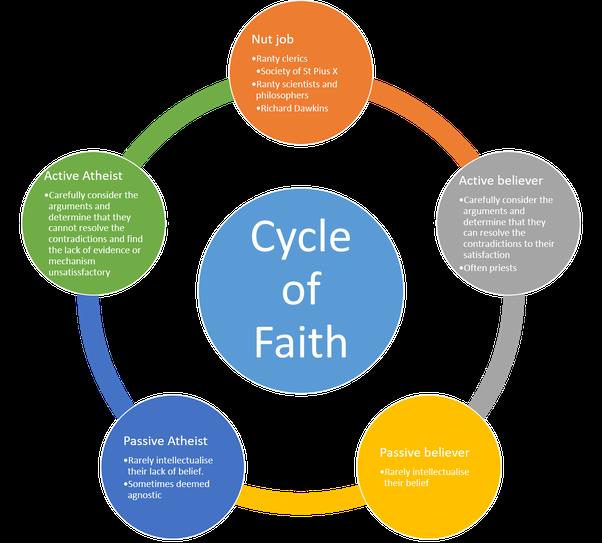

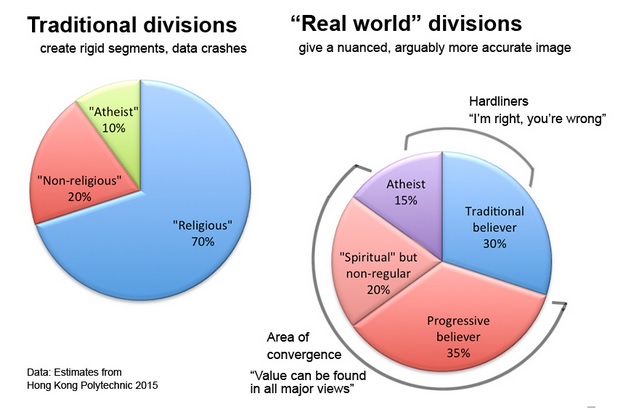

Types of anti-theism depicted in the figure below:

Most atheists do not consider themselves anti-theists but merely non-theists.

______

______

Typology of Nonbelief: a study:

Many assume that nonbelievers are a monolithic group with no variation such as Atheism or Agnosticism. Various studies found that individuals have shared definitional agreement but use different words to describe the different types of Nonbelief. Moreover, social tension and life narrative play a role in shaping one’s ontological worldview. Through thematic coding, a typology of six different types of Nonbelief was observed in this study. Those are Academic Atheists, Activist Atheist/Agnostics, Seeker Agnostics, Antitheists, Nontheists, and the Ritual Atheists.

- Intellectual Atheist / Agnostic (IAA):

The first and most frequently discussed type is what could be termed The Intellectual Atheist / Agnostic or IAA. IAA typology includes individuals who proactively seek to educate themselves through intellectual association, and proactively acquires knowledge on various topics relating to ontology (the search for Truth) and non-belief. They enjoy dialectic enterprises such as healthy democratic debate and discussions, and are intrinsically motivated to do so. These individuals are typically versed in a variety of writings on belief and non-belief and are prone to cite these authors in discussions. IAAs associate with fellow intellectuals regardless of the other’s ontological position as long as the IAA associate is versed and educated on various issues of science, philosophy, “rational” theology, and common socio-political religious dialog. They may enjoy discussing the epistemological positions related to the existence or non-existence of a deity. Besides using textual sources such as intellectual books, IAAs may utilize technology such as the Internet to read popular Blogs, view Youtube videos, and listen to podcasts that fall in line with their particular interests. Facebook and other online social networking sites can be considered a medium for learning or discussion. However, not only is the IAA typically engaged in electronic forms of intellectualism but they oftentimes belong to groups that meet face to face offline such as various skeptic, rationalist and freethinking groups for similar mentally stimulating discussions and interaction. The Modus operandi for the Intellectual Atheist /Agnostic is the externalization of epistemological orientated social stimulation.

- Activist Atheist / Agnostic (AAA):

The next typology relates to being socially active. These individuals are termed the activist atheist and/or agnostic. Individuals in the Activist Atheist typology are not content with the placidity of simply holding a non-belief position; they seek to be both vocal and proactive regarding current issues in the atheist/agnostic socio-political sphere. This socio-political sphere can include such egalitarian issues, but is not limited to: concerns of humanism, feminism, Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgendered (LGBT) issues, social or political concerns, human rights themes, environmental concerns, animal rights, and controversies such as the separation of church and state. Their activism can be as minimal as the education of friends or others, to much larger manifestations of social activities such as boycotting products, promoting legal action, or marching to raise awareness. Activist Atheists / Agnostics are commonly naturalistic or humanistic minded individuals, but are not limited to these types of ethical concerns. It is not uncommon for AAA individuals to ally themselves with other movements in support of social awareness. The Activist Atheist / Agnostic’s are not idle; they effectuate their interests and beliefs.

- Seeker-Agnostic (SA):

The third typological characteristic is the Seeker-Agnostic. Seeker-Agnostic typology consists of individuals attuned to the metaphysical possibilities precluding metaphysical existence, or at least recognizes the philosophical difficulties and complexities in making personal affirmations regarding ideological beliefs. They may call themselves agnostic or agnostic-atheist, as the SA simply cannot be sure of the existence of God or the divine. They keep an open mind in relation to the debate between the religious, spiritual, and antitheist elements within society.

Seeker-Agnostics recognize the limitation of human knowledge and experience. They actively search for and respond to knowledge and evidence, either supporting or disconfirming truth claims. They also understand, or at least recognize, the qualitative complexities of experiences in the formation of personal meaning. Seeker Agnostics do not hold a firm ideological position but always search for the scientifically wondrous, and experientially profound confirmation of life’s meaning. They may be intrinsically motivated to explore and seek understanding in the world around them. The diversity of others is accepted for the SA and co-existence with the “others” is not only possible, but also welcomed. Their worldly outlook may be mediated by science; however, they recognize current scientific limitations and embrace scientific uncertainty. They are comfortable with this uncertainty and even enjoy discussing it. Some Intellectual Atheist /Agnostics or Anti-Theists may accuse the seeker agnostic of avoiding responsibility or commitment to a more solid affirmation of Atheism. In other cases, outsiders may see it as an ontological transitional state from religion or spirituality to Atheism. In some cases, Seeker-Agnostics may generally miss being a believer either from the social benefits or the emotional connection they have with others such as friends or family. At times, their intellectual disagreement with their former theology causes some cognitive dissonance and it is possible they may continue to identity as a religious or spiritual individual. However, taking those exceptions into account, the majority of Seeker Agnostics should in no way be considered “confused.” For the Seeker-Agnostic, uncertainty is embraced.

- Anti-Theist:

The fourth typology, and one of the more assertive in their view, termed the Anti-Theist. While the Anti-Theists may be considered atheist or in some cases labelled as “new atheists,” the Anti-Theist is diametrically opposed to religious ideology. As such, the assertive Anti-Theist both proactively and aggressively asserts their views towards others when appropriate, seeking to educate the theist’s in the passé nature of belief and theology. In other words, antitheists view religion as ignorance and see any individual or institution associated with it as backward and socially detrimental. The Anti-theist has a clear and – in their view, superior – understanding of the limitations and danger of religions. They view the logical fallacies of religion as an outdated worldview that is not only detrimental to social cohesion and peace, but also to technological advancement and civilized evolution as a whole. They are compelled to share their view and want to educate others into their ideological position and attempt to do so when and where the opportunity arises. Some Anti-Theist individuals feel compelled to work against the institution of religion in its various forms including social, political, and ideological while others may assert their view with religious persons on an individual basis. The Anti-Theist believes that the obvious fallacies in religion and belief should be aggressively addressed in some form or another. Based on personalities, some Anti-Theists may be more assertive than others; but outsiders and friends know very clearly where they stand in relation to an Anti-theist. Their worldview is typically not a mystery. The Anti-Theist’s reaction to a religious devotee is often based on social and psychological maturity.

- Non-Theist:

The fifth typology termed the non-theist. While not many individuals identified themselves as this type, they did have experiences with others who indicated themselves as being non-theists. For the Non-Theists, the alignment of oneself with religion, or conversely an epistemological position against religion can appear quite unconventional from their perspective. However, a few terms may best capture the sentiments of the Non-Theist. One is apathetic, while another may be disinterested. Non-Theist is non-active in terms of involving themselves in social or intellectual pursuits having to do with religion or anti-religion. A non-theist simply does not concern him or herself with religion. Religion plays no role or issue in one’s consciousness or worldview; nor does a nontheist have concern for the atheist or agnostic movement. No part of their life addresses or considers transcendent ontology. They are not interested in any type of secularist agenda and simply do not care. Simply put, Non-Theist’s are apathetic non-believers. They simply do not believe, and in the same right, their absence of faith means the absence of any thing religion in any form from their mental space.

- Ritual Atheist/Agnostic (RAA):

The sixth and final type was one of the most interesting and unexpected. This study termed this type The Ritual Atheist / Agnostic or RAA. The RAA type holds no belief in God or the divine, or they tend to believe it is unlikely that there is an afterlife with God or the divine. They are open about their lack of belief and may educate themselves on the various aspects of belief by others. One of the defining characteristics regarding Ritual Atheists/Agnostics is that they may find utility in the teachings of some religious traditions. They see these as more or less philosophical teachings of how to live life and achieve happiness than a path to transcendental liberation. Ritual Atheist / Agnostics find utility in tradition and ritual. For example, these individuals may participate in specific rituals, ceremonies, musical opportunities, meditation, yoga classes, or holiday traditions. Such participation may be related to an ethnic identity (e.g. Jewish) or the perceived utility of such practices in making the individual a better person. Many times Ritual Atheist / Agnostics may be misidentified as spiritual but not religious, but they are quick to point out that they are atheist or agnostic in relation to their own ontological view. For other Ritual Atheist / Agnostics, it may be simply that they hold respect for profound symbolism inherent within religious rituals, beliefs, and ceremonies. The Ritual Atheist / Agnostic individual perceive ceremonies and rituals as producing personal meaning within life. This meaning can be an artistic or cultural appreciation of human systems of meaning while knowing there is no higher reality other than the observable reality of the mundane world. In some cases, these individuals may identify strongly with religious traditions as a matter of cultural identity and even take an active participation in religious rituals. While Ritual Atheists may celebrate their association with ritualistic organizations or call themselves cultural practitioners of a faith-based practice, they are open and honest about their ontological position and do not hide their lack of belief in the metaphysical or divine. Ritual Atheist /Agnostics may identify ritualistically or symbolically with Judaism, Paganism, Buddhism, or Laveyan Satanism to name some examples.

_______

Postmodernism:

Postmodernism does away with many of the things that religious people regard as essential. For postmodernists every society is in a state of constant change; there are no absolute values, only relative ones; nor are there any absolute truths. This promotes the value of individual religious impulses, but weakens the strength of ‘religions’ which claim to deal with truths that are presented from ‘outside’, and given as objective realities. In a postmodern world there are no universal religious or ethical laws, everything is shaped by the cultural context of a particular time and place and community. In a postmodern world individuals work with their religious impulses, by selecting the bits of various spiritualties that ‘speak to them’ and create their own internal spiritual world. The ‘theology of the pub’ becomes as valid as that of the priest. The inevitable conclusion is that religion is an entirely human-made phenomenon.

This is not a very new development. In Japan, many people have adopted both Shinto and Buddhist ideas in their religious life for some time. In parts of India, Buddhism co-exists with local tribal religions. Hinduism, too, is able to incorporate many different ideas. In a world where there is no objectively existing God “out there”, and where the elaborate sociological and psychological theories of religion don’t seem to ring true, the idea of regarding religion as the totality of religious experiences has some appeal. Religion in this theory is created, altered, renewed in various formal interactions between human beings. Images and ideas of God are manufactured in human activity, and used to give specialness (‘holiness’?) to particular relationships or policies which are valued by a particular group. There is no one ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ religion – or sanctifying theory. There are as many as there are groups and interactions, and they merge and join, divide and separate over and over again. Some are grouped together under the brand names of major faiths, and they cohere with varying degrees of consistency. Others, although clearly religious in their particular way, would reject any such label.

Some of these interactions are labelled ‘religious’: rites of passage like weddings and funerals, regular worship services, prayer meetings, meditation sessions, retreats. Some of these are just the rituals of everyday life. These include cooking and cleaning, and working. (Many established religions had that insight a long time ago – although they required the actions to be carried out with a particular attitude of mind to count as religious.) Yet others are group actions designed to “bring about the Kingdom of God” on earth. These are often initiatives for social change, or charity work, or fighting for individual human rights. These dramas remove religion from the exclusive narratives of scriptures, or the lifestyle rules of various faith communities, and bring religion into everyday life. They enable people from different faiths, or none, to work together in religious acts when they engage in social action – they are working to bring about the Kingdom of God on earth, and they don’t worry about who God is, or whether God is or not.

______

______

Introduction to atheism:

_

Atheism may be defined as the mental attitude which unreservedly accepts the supremacy of reason and aims at establishing a lifestyle and ethical outlook verifiable by experience and the scientific method, independent of all arbitrary assumptions of authority and creeds.

-Madalyn Murray O’Hair (1963)

_

Atheism is traditionally defined as disbelief in the existence of a god. As such, atheism involves active rejection of belief in the existence of at least one god. This definition does not capture the atheism of many atheists, which is based on an indifference to the issue of the existence of gods. This attitude of indifference is sometimes called apatheism. There is a difference between disbelief in all gods and no belief in a particular god. Before one can disbelieve in something, that something must be intelligible and it must be understood. Since there are many concepts of gods and these concepts are usually rooted in some culture or tradition, atheism might be defined as the belief that a particular word used to refer to a particular god is a word that has no reference. Thus, there are as many different kinds of atheism as there are names of gods or groups of gods. Some atheists may know of many gods and reject belief in the existence of all of them. Such a person might be called a polyatheist. All theists are atheists in the sense that they deny the existence of all other gods except theirs, but they don’t consider themselves atheists. Most people today who consider themselves atheists probably mean that they do not believe in the existence of the local god. For example, most people who call themselves atheists in a culture where the dominant god is the Jewish, Christian, or Islamic god (i.e., Abraham’s god) would mean, at the very least, that they do not believe that there is an omnipotent, omniscient, providential creator of the universe. Atheism is often considered to be a negative, dark, and pessimistic belief that is characterized by a rejection of values and purpose and a fierce opposition to religion. However atheism shows how a life without religious belief can be positive, meaningful, and moral. Atheists can be indifferent rather than hostile to religious belief. They can be more sensitive to aesthetic experience, more moral, or more attuned to natural beauty than many theists. There is no more reason for them to be pessimistic or depressive than there is for the religious to be so.

__

There have been many thinkers in history who have lacked a belief in God. Some ancient Greek philosophers, such as Epicurus, sought natural explanations for natural phenomena. Epicurus was also to first to question the compatibility of God with suffering. Forms of philosophical naturalism that would replace all supernatural explanations with natural ones also extend into ancient history. During the Enlightenment, David Hume and Immanuel Kant give influential critiques of the traditional arguments for the existence of God in the 18th century. After Darwin (1809-1882) makes the case for evolution and some modern advancements in science, a fully articulated philosophical worldview that denies the existence of God gains traction. In the 19th and 20th centuries, influential critiques on God, belief in God, and Christianity by Nietzsche, Feuerbach, Marx, Freud, and Camus set the stage for modern atheism.

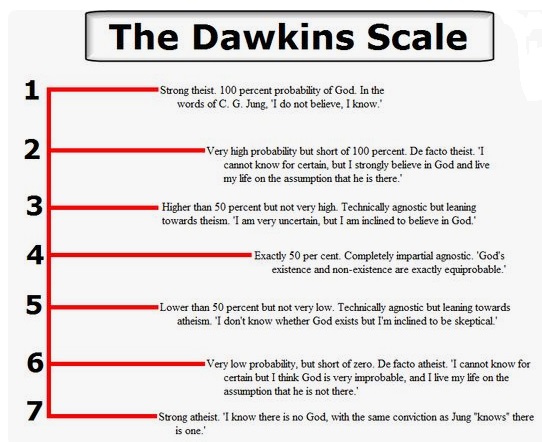

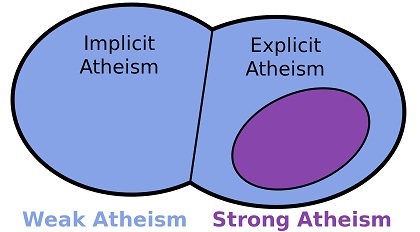

It has come to be widely accepted that to be an atheist is to affirm the non-existence of God. Anthony Flew (1984) called this positive atheism, whereas to lack a belief that God or gods exist is to be a negative atheist. Parallels for this use of the term would be terms such as “amoral,” “atypical,” or “asymmetrical.” So negative atheism would include someone who has never reflected on the question of whether or not God exists and has no opinion about the matter and someone who had thought about the matter a great deal and has concluded either that he/she has insufficient evidence to decide the question, or that the question cannot be resolved in principle. Agnosticism is traditionally characterized as neither believing that God exists nor believing that God does not exist.

Atheism can be narrow or wide in scope. The narrow atheist does not believe in the existence of God (an omni- being). A wide atheist does not believe that any gods exist, including but not limited to the traditional omni-God. The wide positive atheist denies that God exists, and also denies that Zeus, Gefjun, Thor, Sobek, Bakunawa and others exist. The narrow atheist does not believe that God exists, but need not take a stronger view about the existence or non-existence of other supernatural beings. One could be a narrow atheist about God, but still believe in the existence of some other supernatural entities. (This is one of the reasons that it is a mistake to identify atheism with materialism or naturalism.)

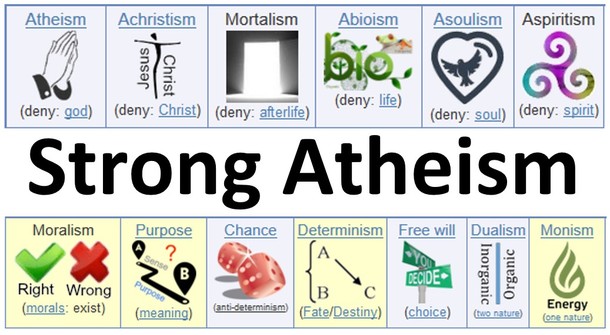

There are two main categories of atheists: strong and weak with variations in between. Strong atheists actively believe and state that no God exists. They expressly denounce the God. Strong atheists are usually more aggressive in their conversations with theists and try to shoot holes in theistic beliefs. They like to use logic and anti-biblical evidence to denounce God’s existence. They are active, often aggressive, and openly believe that there is no God. Agnostic Atheists are those who deny God’s existence based on an examination of evidence. Agnosticism means ‘not knowing’ or ‘no knowledge.’ They state they have looked at the evidence and have concluded there is no God, but they say they are open to further evidence for God’s existence. Weak atheists simply exercise no faith in God. The weak atheist might be better explained as a person who lacks belief in God the way a person might lack belief that there is a green lizard in a rocking chair on the moon; it isn’t an issue. He doesn’t believe it or not believe it. Finally, there is a group of atheists called militant atheists. They are, fortunately, few in number. They are usually highly insulting and profoundly terse in their comments to theists. They are vile, rude, and highly condescending. Their language is full of insults, profanity, and blasphemies. Basically, no meaningful conversation can be held with them.

Separating these different senses of the term allows us to better understand the different sorts of justification that can be given for varieties of atheism with different scopes. An argument may serve to justify one form of atheism and not another. For Instance, alleged contradictions within a Christian conception of God by themselves do not serve as evidence for wide atheism, but presumably, reasons that are adequate to show that there is no omni-God would be sufficient to show that there is no Islamic God.

Some of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining atheism arises from difficulty in reaching a consensus for the definitions of words like deity and god. The plurality of wildly different conceptions of God and deities leads to differing ideas regarding atheism’s applicability. The ancient Romans accused Christians of being atheists for not worshiping the pagan deities. Gradually, this view fell into disfavour as theism came to be understood as encompassing belief in any divinity. With respect to the range of phenomena being rejected, atheism may counter anything from the existence of a deity, to the existence of any spiritual, supernatural, or transcendental concepts, such as those of Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Taoism.

_