Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

SCIENCE OF TRUTH

Science of Truth:

______

_____

Prologue:

I published article ‘The Lie’ on my website on June 5, 2010 wherein I showed how media lied for several decades by saying that Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe died ‘childless’ in the year 1962. “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth”, is a law of propaganda often attributed to the Nazi Joseph Goebbels. Discussion on ‘lie’ is incomplete unless you discuss the ‘truth’. So what is truth? The question is one of the most ancient in philosophy. It was famously posed by Plato, who asked whether there exist eternal truths or whether, to the contrary, man is the measure of all things. Diderot and d’Alembert, in their Encyclope´die (1751–1772), proposed a simple and straightforward answer: truth consists in conformity of our judgments with things. In other words, something is true when there is a fit between thought and object: This implies not only the conformity of our ideas with external objects, but also the internal consistency of our ideas with one another. Yet a great many theories that seem to conform to what we see turn out on closer examination to be false. The sun, despite appearances to the contrary, does not in fact revolve around the earth. And many arguments that seem to be sound ultimately are found to be flawed. Does this justify us, then, in placing confidence in Astrology, Homeopathy, Ayurveda, miraculous powers, or supernatural phenomena? Where are we to draw a line between beliefs and established truths, between opinion and scientific knowledge? What are the distinguishing features of the truths produced by science? These questions lead on to others. Along with error, delusion, and fantasy, there can be conscious falsification—in a word, lying. The person who lies knows it; the person to whom the lie is addressed may not. How is it that we are able to detect deception? Why is the capacity to lie a characteristic trait of the human species? Is it not the counterpart to our ability to tell the truth—something that is impossible for dogs or monkeys? William Hazlitt (1778-1830), a British writer, once asserted that, ‘‘life is the art of being deceived.’’ Human social relations are so steeped in deception that it is impossible to imagine life without it.

_

If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.

-Mark Twain.

This quote means that, in order to be a good liar, or tell a very good lie, you have got to remember what you said exactly, how you said it and be able to re-tell it in the same manner over and over to gain credibility. Also to save a lie, you have to speak many more lies.

_

Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth.

-Buddha

_

Even if you are a minority of one, the truth is the truth.

-Mahatma Gandhi

_

The truth is rarely pure and never simple.

-Oscar Wilde

_

It is time to discuss science of truth….

_______

_______

Introduction to truth:

There is a prevailing intellectual indifference to coherence, logic, rationality, and evidence. It’s a world-view that holds that there is no historical truth and almost everything is a mere social construction. Discovery is conflated with invention, myth is elevated alongside empirical evidence, and no lines are drawn between fact and fiction…the main point is that truth matters because human beings are the only species capable of finding it out. There may be nothing uniquely human about deception: some experts say chimpanzees can fake out rivals. But lying requires something special that, so far, seems the sole province of humans: a theory of mind. To lie effectively, one has to have a notion that other people have minds and can be deceived. By the time most children are 4, they have acquired the ability to deceive others, a skill critical to survival. For example, shown a tube of Smarties candy filled with pencils, 4-year-olds can imagine that other children who don’t know the trick will falsely assume that the tube contains candy. In other words, these normal 4-year-olds have learned that others can be fooled by a false belief. Some brain illnesses like autism interfere with this skill. Most autistic children fail at the false belief task and, by inference would have a hard time deceiving others.

_

Aristotle defines truth for classical philosophy: ‘to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.’ This seems simple, but it is important to see that it is not. The formula synthesizes three distinct and in no way obvious or unobjectionable assumptions, assumptions which prove decisive for the career of truth in philosophy. First, the priority of nature over language, culture, or the effects of historical experience. One can say of what is that it is just in case there exists a what which is there, present, with an identity, form, or nature of its own. Second, the idea that truth is a kind of sameness, falsity a difference, between what is said and what there is. To accommodate the priority of nature, however, truth has to be a secondary sort of sameness: according to the classical metaphor, the imitation of original by copy. It is up to us to copy Nature’s originals, whose identity and existence are determined by causes prior to and independent of local convention. Thus a third feature of classical truth: the secondary and derivative character of the signs by which truth is symbolized and communicated. Classical truth subordinates the being (the existence and identity) of signs (linguistic or otherwise) to the natural, physical, finally given presence of the non-signs they stand for.

_

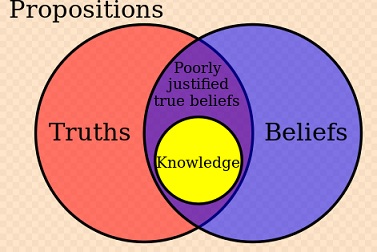

Truth is most often used to mean being in accord with fact or reality, or fidelity to an original or standard. Truth may also often be used in modern contexts to refer to an idea of “truth to self,” or authenticity. The commonly understood opposite of truth is falsehood, which, correspondingly, can also take on a logical, factual, or ethical meaning. The concept of truth is discussed and debated in several contexts, including philosophy, art, and religion. Many human activities depend upon the concept, where its nature as a concept is assumed rather than being a subject of discussion; these include most (but not all) of the sciences, law, journalism, and everyday life. Some philosophers view the concept of truth as basic, and unable to be explained in any terms that are more easily understood than the concept of truth itself. Commonly, truth is viewed as the correspondence of language or thought to an independent reality, in what is sometimes called the correspondence theory of truth. Other philosophers take this common meaning to be secondary and derivative. According to Martin Heidegger, the original meaning and essence of “Truth” in Ancient Greece was unconcealment, or the revealing or bringing of what was previously hidden into the open, as indicated by the original Greek term for truth, “Aletheia.” On this view, the conception of truth as correctness is a later derivation from the concept’s original essence, a development Heidegger traces to the Latin term “Veritas.” Pragmatists like C.S. Peirce take Truth to have some manner of essential relation to human practices for inquiring into and discovering Truth, with Peirce himself holding that Truth is what human inquiry would find out on a matter, if our practice of inquiry were taken as far as it could profitably go: “The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth…”

_

Philosophers have long sought to understand and define truth. For so long truth was the preserve of philosophers and theologians, but then came the Enlightenment, and science and rationalism stepped in. Today science’s binary approach to seeking truth is well accepted: through observation and experimentation, we arrive at either-or, true-false conclusions. But is truth a simple matter of true or false, black or white, this or that? Going a step further, is the way to truth a binary choice between traditional religion/ philosophy and science. For most people today, however, truth is simply the opposite of falsehood. This idea is well entrenched in our societies, which commonly use true-or-false questions to test students all the way up to the university level. It’s a purely rational and logical way of looking at things, and it is at the heart of the belief that human beings can ultimately know all there is to know through reason. We may not have the answer today, but given time, it will be discovered. In Europe during the medieval and early modern period, three “estates” helped shape the ideas by which societies were governed. The make-up of these estates varied from country to country and from time to time, but they represented layers of citizenry under the monarch, often expressed as clergy, nobility and common people. At any given time, the monarch or one of these three entities held sway; so power to steer the masses (and thus dictate “truth”) might lie at different times with the king, or with the church, the wealthy or eventually the commoners themselves. In the early 19th century some in Britain noted the rise of a fourth estate, namely the media; they began to see the newspapers of their time as a powerful additional force in shaping ideas and establishing truth. But that wasn’t the final word, of course. Knowledge increased, and by the early 20th century science had come to be viewed by some as a fifth estate. In fact, scientific methods and proofs have become much more rigorous over the past century and in the minds of many have fully replaced all earlier approaches, in particular philosophy and religion, as the way to truth. Exact results can be established, after all, by a process of repeated experimentation. This is empirical truth—that which is based on observation and experience.

_

By whatever means people seek truth, however, they often have difficulty distinguishing it from the seeming reality of their own perceptions. Society by its standards and approaches feeds this misconception. Our law courts claim to operate on the basis of truth, but they allow it to be shaped by the perceptions of the plaintiff, the defendant and the witnesses. The incidence of false convictions undermines such notions of truth. Journalism is also supposed to be based on a pursuit of truth, but that too depends largely on the perceived reality of the reporter or the editor. Even science may be based on the perceived reality of the scientist. Biologist and renowned atheist Richard Dawkins has made a name for himself by loudly proclaiming that reason is the only means by which truth can be established or known—that truth is what is discoverable by the human intellect, the product of our rational understanding and our increasing knowledge. Still, one of the chapters in his book The God Delusion is titled “Why There Almost Certainly Is No God”, suggesting that Dawkins’s deeply held convictions about the nonexistence of God are less absolute truth than perception—his admittedly unproven and unprovable belief that God exists only in people’s imaginations.

__

Truth-telling is one of the only moral imperatives across cultures. Why would that be? Simply put, human communication is pointless unless we assume that others will tell the truth. If I ask you what time it is or for directions to London, I’m assuming you won’t lie. If I assume the opposite, there’s not much point to the question. Sincere, honest exchange essentially is communication, all the rest just manipulation. Other problem with lies, ignorance, and bullshit is that they undermine our rationality; they leave us slaves to our passions; and they keep us groping in the dark when we try to solve problems. Problems are hard to solve when you start with truth, much more so when you begin with falsehoods. Lies and nonsense will ultimately be our downfall, however temporarily attractive they may be. But why? If we disregard the truth we’ll undo the project of classical Greece and the Enlightenment, when humans realized that reason could improve their world; if we disregard the truth we will remain slaves to the reptilian impulses of our anciently-formed brains; if we disregard the truth we’ll destroy our planet’s atmosphere and biosphere and kill ourselves. People suffer when the truth is distorted. So it is our choice. Face the truth of our biological and cultural heritage and transcend them, or we will all perish.

______

Three principles of truth:

There are three basic principles of truth: the so-called fundamental principle of truth, manifold correspondence principle, and logicality principle. The fundamental principle says that truth, as a standard for human thought, arises at the juncture of three basic modes of cognition: immanence, transcendence, and normativity. The manifold correspondence principle says that truth in all fields requires a substantial and systematic relation between thought and world, yet this relation may assume multiple forms, including relatively complex forms. The logicality principle says that a partial yet important factor in determining the truth value of thoughts is their logical structure.

______

Truth and its sources:

Truth expresses our general understandings of how the world works, that is, what it is and what it means. It expresses our belief that the world is a knowable place with relatively stable patterns that are accessible to people like us. Truth links objective goings-on with subjective experience. When we pledge to “tell the truth” in a court of law (and perhaps “the whole truth and nothing but the truth”), our vow is to produce statements that correspond to beliefs we actually hold. Where do these feelings of certainty – and of consistency between behaviors and understandings – come from? Consider first the idea that truth has different bases or “sources.” And those sources sometimes lead to contradictory conclusions.

- A first of these is authority. Many statements we accept because a person we respect (or who is in a position we respect) says they are true. In that spirit, we listen to our doctors, teachers, religious leaders, and coaches.

- A second source is tradition. Many things are believed because they’ve always been believed, or so we think. Great myths about the origins and destinies of countries and peoples are of this sort. So is folk wisdom about all manner of things – the causes and cures of various health conditions, the characteristics of different “kinds” of peoples, and so forth

- There is also intuition. Some beliefs are consonant with deep feelings we have. That sense of rightness eludes our ability to comprehend it. As Pascal famously put it, “The heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing.” So inspired we commit to our very private sense that there is – or isn’t – a God. We declare that we are “in love,” or decide that what we feel isn’t quite enough.

- Fourth is common sense. Our experiences of practical, everyday affairs are important to our understandings of how the world operates – and to our judgment that other people are being straight with us. By such criteria, we decide that an advertisement promises a deal that is just “too good to be true.” We reject an ordinary-looking person’s claim that they are a top model. Such judgments come from the trials-and-errors of living, and from sharing information with other people who have lived through similar circumstances. In that latter sense, our beliefs are “common.”

- Fifth is logic. The logical person believes that he or she can proceed to truth by following correct processes of reasoning. If we start with certain premises, then we can appropriately deduce certain conclusions. “If all bears are animals, and Joe is a bear, then Joe is certainly an animal.” Knowing Joe is an animal does not mean, however, that he is a bear. Some of the greatest philosophers and theologians have tried to comprehend the world is such ways. And the rest of us use less exalted forms of logic to reach our own conclusions.

- Sixth, and last, is science. Science tests the truth of propositions by systematically collecting “facts.” There is a real world that moves ahead on its own terms. We trust our sense-based perceptions of it. But only if other people are experiencing it in a like way. In that spirit, we record and count.

______

______

Subjective, objective and absolute truth:

There are differing claims on such questions as what constitutes truth: how to define and identify truth; the roles that faith-based and empirically based knowledge play; and whether truth is subjective or objective, relative or absolute. In general, absolute truth is whatever is always valid, regardless of parameters or context. The absolute in the term connotes one or more of: a quality of truth that cannot be exceeded; complete truth; unvarying and permanent truth. It can be contrasted to relative truth or truth in a more ordinary sense in which a degree of relativity is implied.

1) In philosophy, absolute truth generally states what is essential rather than superficial – a description of the Ideal (to use Plato’s concept) rather than the merely “real” (which Plato sees as a shadow of the Ideal). Among some religious groups this term is used to describe the source of or authority for a given faith or set of beliefs, such as the Bible.

2) In science, doubt has been cast on the notion of absolutes by theories such as relativity and quantum mechanics.

3) In pure mathematics , however, there is said to be a proof for the existence of absolute truth. A common tactic in mathematical proofs is the use of reductio ad absurdum, in which the statement to be proved is denied as a premise, and then that premise is shown to lead to a contradiction. When it can be demonstrated that the negation of a statement leads to a contradiction, then the original statement is proved true. The logical proof of the statement, “There exists an absolute truth,” is almost trivial in its simplicity. Suppose we assert the negation of the statement, that is, that there is no such thing as absolute truth. By making that assertion, we claim that the sentence “There exists no absolute truth” is absolutely true. The statement is self-contradictory, so its negation, “There exists an absolute truth,” is true. This proof applies only to logic. It does not tell us whether any particular statement other than itself is true. It does not prove the existence (or non-existence) of God, the devil, heaven, hell, or people from another galaxy. Neither does it assert that we can always ascertain the truth or falsity of any arbitrary statement. The Incompleteness Theorem , proved by Kurt Gödel and published in 1931, actually showed that there exist logical statements whose truth value is undecidable, that is, they cannot be proved either true or false.

_

The word truth can have a variety of meanings, from honesty and faith to a verified fact in particular. The term has no single definition about which a majority of professional philosophers and scholars agree, and various theories of truth continue to be debated. There are differing claims on the roles that revealed and acquired knowledge play; and whether truth is subjective, objective, or absolute. The ways by which we acquire knowledge, can be differentiated into four broad categories, sense perception, language, emotion and reasoning. The four ways of knowing help us to identify and differentiate between subjective and objective truths. It is generally assumed language gives us access to subjective truths while reason gives us access to objective truths. For example, the various mathematical proofs, theories and formulae that are in use today are in practice because of they have been proved by reason and are considered as objective mathematical truths. However, some theories and formulas are axiomatic truths. Axiomatic truths are self-evident truths or basic facts which are accepted without any proof. On the other hand, perception and emotion are believed to result in subjective truths. From past experiences, I have generalized that objects left out in the rain get wet. Through reasoning I apply this understanding to tonight’s rainfall, and conclude that my own bicycle will get wet if it is left out in the backyard. Reason can help us to identify both subjective and objective truths. For example, reason can help to distinguish between objective mathematical truths and subjective artistic truths. Thus it can be seen that the various ways of knowing alone can help to identify truths: and the ways of knowing may also work together to give us the truth. For example, in science the way of knowing of reason and sense perception may work collaboratively to give us the objective truths. Reason is not necessarily superior to the other ways of knowing because each of the ways of knowing has its own limitations and may not necessarily give us the absolute truth. The way of classical inductive reasoning can lead to false claims. Consider this example, I saw a duck and it was black. I saw a second duck and it was black. I saw a third duck and it was black. I saw an nth duck and it was black. A general statement becomes the conclusion “All ducks must be black”. After tens of thousands of instances of black ducks in Africa, Asia and North America I go to the UK and see a white duck, right in the middle of a lake. One false instance is enough to topple over the general conclusion I had painstakingly reached. In the wake of the development in sciences and the extensive use of reason in daily life, a question is raised “Is reason the most superior way of knowing?” Reason has given rise to many scientific explanations and theories such as the formulae of mathematics and the laws of physics. In science, the various laws of gravity in physics have been defined after reason and research. For example, if I observe that the gravity is always same when I undertake an experiment, by inductive reasoning I will assume that this will always be the case if I measure gravity on any place in the world. The general statement becomes the conclusion “The acceleration due to gravity is 9.8 meter/second-squared. But, if I were to conduct the same experiment at the North or the South Pole I would find that the value of gravity is more than what I had found before, as the earth is elliptical and the poles are closer to the earth’s core. Also, the value of gravity would be quite different if I were to conduct the same experiment at the equatorial regions. Thus, as we can see, the reasoned assumption can sometimes lead to a paradigm shift i.e. true in specific environments so not a universal truth. Even if the experiment is conducted hundreds of times, there is always a possibility that an exception will be found and the theory would be falsified like in the case of the white duck. Thus, it is suggested that a hypothetical deductive method should be used, which is a continual interplay between deductive and inductive reasoning, mediated by testing done in the real world, whereby false hypotheses are discarded through trial and disproof. However, there is a possibility that somebody may stumble upon a case that falsifies the conclusion.

_

The other knowledge issue raised is “How far do our cultural beliefs distort our attempts to distinguish between subjective and objective theories?”. For example, a case in India, where cultural beliefs are followed on a large extent, the idols of Lord Ganesha in temples all over the country were believed to be drinking milk from the offerings by visitors and followers. Thus, the subjective truth of all the followers was that the idol of Lord Ganesha was drinking milk. However, scientists conducted various experiments on the idols thereafter and came out with an objective explanation whereby the subjective truth of the followers was falsified. The rationalists and the scientists proved that the result was because of the surface tension and the absorption capabilities of the materials of which the idols were made. Thus, the cultural belief in India that the offerings by devotees are consumed by the God, gave rise to the subjective truth and distorted the objective truth.

_

Also, another knowledge issue which is raised is “How to do we get from our subjective beliefs to our objective truths?”. Darwin’s theory of evolution was based on his observations and is believed to be true especially by most of today’s scientists. Darwin’s subjective belief in evolutionary theory was transformed into an objective truth. He proposed that all of the millions of species of organisms present today, including humans, evolved slowly over billions of years, from a common ancestor by way of natural selection. However, certain counter-claims make us believe that the theory of evolution is false. According to the theory of natural selection birds could never evolve to fly while this is certainly not the case. Though subjective beliefs can be and have been transformed into objective truths by repeated experimentation, it is possible that a single counter-claim could forge the conclusion and prove the theory to be wrong. Though, evolution knows how to deal with a paradox like this: explain it away, rationalize it. That is science. Science explains paradox and exceptions. Early birds may have used their wings not for flying, but for running. By flapping their front appendages, the animals gained more traction as they were running up steep inclines. Also natural selection is not the only source of design in nature.

_

The distinction between subjective and objective truths also raises the knowledge issue ‘Is emotion an effective way of distinguishing between subjective and objective truths?’ For example, in Ethics we may use reason effectively to distinguish between the reasons why we should switch off a life-support machine on a family member and why we shouldn’t, but reason may not take into account the emotional pressures we feel in the moment of flicking the switch, or emotion may even over-rule reason to some extent.

_

The ongoing debate between subjective and objective truths also raises the knowledge issue ‘Are there any absolutely certain objective truths independent of what we believe to be true?’ This knowledge issue takes into account absolute truths. An absolute truth, sometimes called a universal truth, is an unalterable and permanent fact. Many religions contain absolute truths. For example, a Christian might believe Lord Jesus to be his saviour. To the Christian this may be an absolute truth. While many may agree that the Christian believes absolutely that Jesus is his Lord, they are unlikely to agree that Jesus is everyone’s Lord is an absolute truth. Centuries of missionary work just failed to do that. Those who do not endorse the absolute truth of another are either pitied or attacked and results in war and oppression.

_

The method of the natural sciences involves perception as part of the collection of data to prove or disprove theories about the natural world for example, the development of the big bang theory by Edwin Hubble was based on his investigation of mysterious masses of stars called Nebulae. However, the problem is that a scientist’s observations may be limited by the instruments they use to make their observations. However, several of these theories are considered as absolute truths today in spite of what we believe. Again, Historians might provide primary sources to represent the absolute objective truth of the horrors of Stalin’s reign of terror, but the problem is this: how do we know that those sources haven’t been tampered with – if Stalin’s regime was capable of doctoring evidence during his rule, isn’t this even more rife in an age where everyone has access to tools to doctor evidence?

_

Suppose you examine an apple and determine that it’s red, sweet, smooth and crunchy. You might claim this is what the apple is. Put another way, you’ve made truth claims about the apple and seemingly made statements about real properties of the apple. But immediate problems arise. Let’s suppose your friend is color blind (this is unknown to you or her) and when she looks at the apple, she says that the apple is a dull greenish color. She also makes a truth claim about the color of the apple but it’s different than your truth claim. What color is the apple? Well, you might respond, that’s an easy problem to solve. It’s actually red because we’ve stipulated that your friend has an anomaly in her truth-gathering equipment (vision) and even though we may not know she has it, the fact that she does means her view of reality is incorrect. But now let’s suppose everyone is color blind and we all see “red” apples as green? We can make this objection even stronger by asking how we know that we all aren’t in fact color blind in a way we don’t understand and apples really aren’t red after all. No one has access to the “real” color of the apple. Again, the response might be that that this is a knowledge problem, not a truth problem. The apple really is red but we all believe it’s green. But notice that the truth of the apple’s color has little role to play in what we believe. No one knows what the truth is and so it plays no role in our epistemology. The challenge is that our view of truth is very closely tied to our perspective on what is true. This means that in the end, we may be able to come up with a reasonable definition of truth, but if we decide that no one can get to what is true (that is, know truth), what good is the definition? Even more problematic is that our perspective will even influence our ability to come up with a definition! If I stretch the argument further, actually there is no color but reflected electromagnetic waves fall in our eyes and our brains interpret some wavelength as color. So apples have no color but we assign color. Apple is red but that redness is in our brain and not in apple. Apple is red is truth but that truth comes from us and not from apple. In other words our brain is the final arbiter of truth.

__

No truth can be ‘objectively verified’ – empirically or otherwise – and the criteria by which we define truths are always relative and subjective. What we consider to be true, whether in morality, science, or art, shifts with the prevailing intellectual wind, and is therefore determined by the social, cultural and technological norms of that specific era. Non-Euclidean geometry at least partially undermines the supposed tautological nature of geometry – usually cited as the cornerstone of the rationalist’s claims that reason can provide knowledge: other geometries are possible, and equally true and consistent. This means that the truth of geometry is once more inextricably linked with your personal perspective on why one mathematical paradigm is ‘truer’ than its viable alternatives. In the end, humans are both fallible and unique, and any knowledge we discover, true or otherwise, is discovered by a human, finite, individual mind. The closest we can get to objective truth is intersubjective truth, where we have reached a general consensus due to our similar educations and social conditioning. This is why truths often don’t cross cultures. This is an idea close to ‘conceptual relativism’ – a radical development of Kant’s thinking which claims that in learning a language we learn a way of interpreting the world, and thus, to speak a different language is to inhabit a different subjective world. So our definition of truth needs to be much more flexible than Plato, Descartes and other philosophers claim. The pragmatic theory of truth is closest: that truth is the ‘thing that works’; if some other set of ideas works better, then it is truer. This is a theory Nietzsche came close to accepting.

_

In an experiment by Solomon Asch, subjects were given pairs of cards. On one were three lines of different lengths; on the other card a single line. The test was to determine which of the three lines was the same length as the single line. The truth was obvious; but in the group of subjects all were stooges except one. The stooges called out answers, most of which were of the same, obviously wrong, line. The self-doubt thus incurred in the real subjects made only one quarter of them trust the evidence of their senses enough to pick the correct answer. Schopenhauer noticed the reluctance of the establishment to engage with new ideas, choosing to ignore rather than risk disputing and refuting them. Colin Wilson mentions Thomas Kuhn’s contention that “once scientists have become comfortably settled with a certain theory, they are deeply unwilling to admit that there might be anything wrong with it” and links this with the ‘Right Man’ theory of writer A.E.Van Vogt. A ‘Right Man’ would never admit that he might be wrong. Wilson suggests that people start with the ‘truth’ they want to believe, and then work backwards to find supporting evidence. Similarly, Robert Pirsig says that ideas coming from outside orthodox establishments tend to be dismissed. Thinkers hit “an invisible wall of prejudice… nobody inside… is ever going to listen… not because what you say isn’t true, but solely because you have been identified as outside that wall.” He termed this a ‘cultural immune system’.

___

“We do not see the world as it is. We see the world as we are.”

This quote has been attributed to both the Talmud and Anaïs Nin (although an actual citation for neither quote can be found). This quote summarizes the idea that truth, the truth that one perceives, is subjective and can be wrong. Our conscious experience is crucial to our grasping truth, to our knowing that we know the truth. We have long been taught that the truth will set us free, and that seeking the truth is a worthy goal. What if there is no absolute truth? What if there are just degrees of truth (or lies) that we tell ourselves? What if, as some insightful, anonymous person once purported, “People tell themselves stories, and then pour their lives into the stories they tell”? Meaning is created in life. Neutral events are made subjective by interpreting them through the lens of perception. “Truth” is merely a product of perceptions; perceptions are colored by experience, which is then filtered through the current state of mind and altered even further. By the time the neutral event is processed in this manner, it is little more truth than fiction. Yet personal truth is accepted wholeheartedly.

_

In an excellent discussion on being wrong, Kathryn Schulz states, “The miracle of your mind isn’t that you can see the world as it is. It’s that you can see the world as it isn’t.” The point of her talk is that we are often not only wrong, but completely unaware of it. She grasps the idea that reality is filtered through perceptions and biases; and that it comes out the other side distorted but believed to be truth. Now, if you are willing to suspend your truth for a moment, and to even momentarily accept that much of what you believe may only be your version of the truth; or that what you believe is not the absolute truth, you may wonder how this is helpful to your state of mind. Despite an initially discouraging reaction to finding you are not as in touch with truth as you had believed, the benefit to this understanding is substantial. First, when you can apply it to daily personal interactions that have heightened emotion, you can slow down the reaction by understanding you and the other individual are simply buying into your truths about the situation. This can diffuse the tension. For example Schulz describes what she calls “a series of unfortunate assumptions.” The first occurs when someone disagrees; it is assumed they are just ignorant of the facts. The solution is then simple, the facts just need to be presented, and the conflict will be resolved. Everyone can relate to this. Unfortunately, we are often stunned when that doesn’t work and the person continues to disagree with us. Often this results in repeating the “facts” in a different way, hoping the person will then understand. This leads to Schulz’s second unfortunate assumption, that the individual must be an idiot; now they have the pieces to the puzzle, “but they are two moronic to put them together correctly.” When we realize that the other has all of the same facts and they aren’t idiots, we resort to the third assumption, that they are evil. She humorously says, “they know the truth, but they are deliberately distorting it for their own malevolent purposes.” These assumptions are detrimental to improving personal relations. So in this way, understanding that a particular version of the truth is not the only one (and that other versions exist) can be very helpful to interpersonal relations.

_

Understanding personal perception may be flawed allows one to question thinking. Questioning thinking can be helpful by realizing events are neutral; then neutral events are provided personal meaning. With this knowledge one can question why a certain meaning was given. For example, when things do not work out as planned, questioning the given meaning allows that a mistake was made in interpreting the events. This is certainly better than believing that one somehow screwed up destiny. As Shawn Achor says in his study of happiness, “Ninety percent of your long term happiness is predicted not by the external world, but by the way your brain processes the world.” As such, it is not believing your truth that will set you free.

______

______

Inductive and deductive truth:

Much of what we consider to be true depends upon our having repeated observations. For example, “The sun will rise tomorrow” is a proposition we believe to be true because we have had many experiences of the sun rising at approximately the same time, leading us to believe that it will rise again with similar periodicity in the future. The statement, “It will probably rain soon” might be given a high degree of credibility because we see a giant cumulus nimbus cloud overhead, and because in many other instances, such a sighting is followed by rain. When I hear the doorbell ring, there’s a good chance someone will be there when I open the door; such as been the case on many other occasions. These are so-called inductive truths. They are not derived from pure reason, but from our experience. We assume that the future will resemble the past. Many of our endeavors rely on inductive reasoning, for example, science, business, and just daily living; basically, wherever we make judgments about the future based on what occurred in the past. Now, inductive truths are notoriously less reliable than formal, deductive truths. They do not share the same apodictic nature of conclusions that depend only on definitions and rules. There are many things that can go wrong with our observations, for example, our senses can play tricks on us; appearances can be deceiving; and with particularly complex experiments, variables can be difficult to control. Underlying all of this is the assumption that there is uniformity in nature, such that the future will resemble the past, and that what we suppose to be physical laws will continue through time and from place to place. It is not irrational to make these assumptions, for they would appear to work for us. However, that by no means proves the truth of our underlying assumptions. As we see in many areas, for example, the stock market, measuring insurance risks, and meteorology, there is no guarantee that the future will resemble the past, or at least, that we can understand the latter well enough to make completely reliable assessments of what will occur.

_______

_______

Etymology of truth:

Truth is from the Proto-Indo European root drew-o- and deru, meaning “be firm, solid, steadfast”, and also hard, accurate, real, upright, “rock solid”, a foundation to stand upon, an axiom. This symbolizes the solid, firm, upright and unshakable steadfastness of reality and existence. The English word true is from Old English (West Saxon) (ge)tríewe, tréowe, cognate to Old Saxon (gi)trûui, Old High German (ga)triuwu (Modern German treu “faithful”), Old Norse tryggr, Gothic triggws, all from a Proto-Germanic trewwj- “having good faith”, perhaps ultimately from PIE dru- “tree”, on the notion of “steadfast as an oak” (e.g., Sanskrit “taru” tree). Old Norse trú, “faith, word of honour; religious faith, belief” (archaic English troth “loyalty, honesty, good faith”, compare Ásatrú). Truth is hard, French dure = deru, solid, firm, it’s enduring and durable. Do you see the connection and what this symbol/term “truth” is referring to? It is clear if you look into the origin of the words to learn what this symbol was created to represent and reflect about reality.

____

Defining Truth:

The simplest and most obvious definition of truth is, without a doubt, that which accords with reality. Here, we can say that truth matters because reality matters. As simple as this is, it is also begging a very important question: just how do we tell what accords with reality and what doesn’t? This is a much more difficult question to answer, one which occupies a great deal of time and attention. Of course, not everyone quite agrees that “truth” is best defined and understood simply as correspondence with reality. That certainly isn’t how everyone uses the term even in normal conversations — and it must be acknowledged that many definitions of truth are derived from a person’s philosophical system.

_

Definitions of truth:

- The state or quality of being true to someone or something.

- Faithfulness, fidelity.

- A pledge of loyalty or faith.

- True facts, genuine depiction or statements of reality.

- Conformity to fact or reality; correctness, accuracy.

- Conformity to rule; exactness; close correspondence with an example, mood, model, etc.

- That which is real, in a deeper sense; spiritual or ‘genuine’ reality.

- Something acknowledged to be true; a true statement or axiom.

- Honesty, reliability, or veracity

- Accuracy, as in the setting, adjustment, or position of something, such as a mechanical instrument

- A verified or indisputable fact, proposition, principle, or the like:

- That which is considered to be the ultimate ground of reality.

____

What is the difference between truth and true?

Truth is a related term of true. As nouns the difference between truth and true is that truth is the state or quality of being true to someone or something while true is truth. As verbs the difference between truth and true is that truth is to assert as true, to declare while true is to straighten. As adjective true is (of a statement) conforming to the actual state of reality or fact; factually correct. As adverb true is accurately.

‘Moment of truth’ is a time when a person or thing is tested, a decision has to be made, or a crisis has to be faced; the phrase has nothing to do with truth or true.

______

Kinds of Truth:

- Eternal truths.

- Authoritative truths.

- Esoteric truths.

- Reasoned truths.

- Evidence-based truths.

- Creative truths.

- Relative truths.

- Powerful truths

- Moral truths.

- Holistic truths.

- Scientific truths

- Religious truths

- Historic truths

- Aesthetic truths

______

Stages of truth:

True statements and ideas are often not recognized initially; instead, the process of acceptance is long and circuitous. The process of acknowledging a truth is broken down into three stages:

- The first stage is ridicule. When a new idea or concept is brought up, it’s so strange that it’s completely absurd. People cannot fathom this idea and how it fits into their lives, so they simply laugh at how impossible it seems.

- The second stage is opposition. After a new concept hasn’t made it past the first stage, people begin to worry that it’s here to stay. A few might support the concept, but most will resist because they see it as a threat to everything they’re familiar with.

- The third stage is self-evident. There is increasing evidence that supports the idea, which goes from having a few early supporters to entering the mainstream. A majority of people support the fact and come to accept it as a given.

The prominent German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer is usually credited with an apothegm of this type.

_____

Why tell truth:

Here are some tips on why you would want to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth no matter what!

- Being true to yourself and true to those around you will make your life a whole lot easier.

- The sooner you tell the truth the easier it is.

- The longer we hold back the truth, the harder it is on others and ourselves.

- When we tell the truth our relationships grow stronger and richer. When we hold back the truth our relationships suffer including our relationship with ourselves.

- Telling the truth creates freedom and lightness. Holding back the truth creates excess baggage. The more we hold back the more baggage we have.

- When we tell the truth we are blessed with intimacy. When we hold back the truth we feel alone and separated.

- Telling the truth increases our ability to be happy. Withholding the truth can cause numbness, apathy, anger and sadness.

- When we tell the truth we become trustworthy. When we hold back the truth people don’t trust us. All relationships are built on trust.

- When you tell the truth it becomes easier to reach your goals. When you withhold the truth reaching your goals is a lot harder.

- When you tell the truth you attract people who also tell the truth. When you hold back the truth you attract needy people that drain you.

- Only humans can discern truth. Of all life on the planet, only humankind can rise above conditioning or instinct and identify truth, so that this is in effect one of the defining characteristics of what it means to be human.

- Truth is an intrinsic part of human history and culture. All our historic and contemporary experience is based on identifying the best possible understanding of truth and building upon this to create a better understanding of our world and our universe.

- Truth is necessary for a consistent and meaningful approach to life. If we do not know whether statements are true, we cannot make reasonable decisions about our life, such as whether to marry an individual or whether to buy a particular property.

- Truth is useful because it enables one to make predictions. If we are confident that things are true, then we can make assertions about the future with equal confidence, such as that a particular design of aircraft is safe or a particular form of sex is dangerous.

- The absence of truth is positively dangerous. If truth does not matter, then we can be persuaded to do things with great personal and societal implications, such as to use an ineffective treatment for HIV/AIDS or to go to war over weapons of mass destruction that do not exist. Equally we can deny the reality of the Holocaust or the evidence of global warming.

_

Theologians and philosophers have identified other reasons as well:

- Authentic Communication Requires Truth-telling:

Truth-telling is essential for authentic communication to occur, and makes genuine interaction between people possible. That is, if truth were not expected, it would not be long before communication would entirely break down. Imagine what it would be like living in a society in which no one expected the truth. How could a person discern what is accurate and what is a falsehood? On what basis could a person make important decisions if there was no expectation of the truth? Life would be chaotic without the norm of honesty. This is essentially the view of the philosopher Immanuel Kant, and the principle of universalizability of truth-telling (though he would not support the notion given here that there are exceptions to the universal norm). Kant argued that this principle was the test of a valid moral principle, and used truth-telling as one of his primary illustrations. He insisted that for a norm to be legitimate, it must be universalizable—applicable to everyone. One of his illustrations envisioned what might happen if no one accepted the norm in question. He correctly argued that without a universal norm of truth-telling, the basis for communication would be in jeopardy, and a society in which this was not a norm would not be functional. This is recognized by the fact that virtually every civilization has some kind of norm that promotes truth-telling and prohibits deception.

- Trust and Cooperation Require Truth-telling:

Truth-telling builds trust and civil cooperation among human beings. Trust is critical for a prosperous society, and being a person of one’s word establishes trust and trustworthiness. Many Proverbs bring out the connection between trustworthiness and social harmony. Adam Smith was very clear that honest dealings and trustworthiness were critical for a properly functioning market system. Cultures that are given to corruption are often in the most impoverished parts of the world, since it is more difficult and risky to do business in cultures in which the level of trust is low. Similarly, companies in which there is a culture of distrust typically have higher costs of doing business, since they require costly regimens of oversight. They also have intangible costs, as employees tend to be more reluctant to “go the extra mile” for their employer and tend to be less eager to embrace change and less committed to their work.

- Human Dignity Requires Truth-telling:

Truth-telling treats people with dignity. To tell someone the truth is a measure of respect that is missing when someone is lied to. The right of a person to make his or her own autonomous decisions is based on having accurate information, so much so that people often and understandably feel violated and disrespected when they are deceived. A person’s autonomy is weakened when they are deceived.

_____

Separating Truth from Falsehood:

How a person conceives of truth will, of course, have a profound influence upon what sorts of criteria they use of differentiating between truth and falsehood. A person who adopts the Correspondence Theory of truth will use one set of criteria while someone who adopts the Semantic Theory of truth will employ different criteria; as a consequence, they could easily look at the exact same claim and reach different conclusions about its truth status. Thus, another fundamental problem which needs to be looked at when discussing truth is: whenever someone claims that some idea is true, what exactly do they mean by “true”? And what does it mean if we say that it isn’t true? They might not mean the same things you mean! It would be difficult to disagree with a person over the truth of a claim if we aren’t speaking the same “language” of truth in the first place. If we define truth differently and use different criteria of truth, then it would be easy to disagree about what is and is not true, but very difficult to reach some sort of common ground. It isn’t unusual for people to employ very different ideas about truth unconsciously, so one of the tasks of epistemology is to develop clear and forthright explanations of the nature of truth which people can discuss out in the open, perhaps even reaching some sort of accord. Thus, it makes a lot of sense to have a clearer understanding about how you and others understand and define truth before disagreeing too strenuously about just what qualifies as true in the first place. That could prevent any number of unnecessary misunderstandings before they go too far.

_

Norman Geisler offers a helpful list of what truth is and what truth is not:

What truth is not:

- Truth is not what works. Pragmatism says an idea is true if it works. Cheating and lying often work, but that does not make them true. How do we measure what works? Says Geisler, “An idea is not true because it works; it works because it is true.”

- Truth is not what feels good. Mysticism and subjectivism both affirm personal feelings as the basis of truth. But feelings can be misleading. And if two person’s feelings conflict, who decides whose is true? Feelings may or may not correspond with what is true.

- Truth is not whatever you want it to be. Relativism says that truth is whatever I declare it to be. But no one can live this way. If I say a traffic light is green when it is really red, there will be serious consequences. As Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “You’re entitled to your own opinion but you’re not entitled to your own facts.”

- Truth is not just what we perceive with the senses. Empiricism says that only what we can measure empirically (with the five senses) is true. But truth is more than this. What about things like justice and love? They cannot be discovered by the five senses. Also our senses can mislead us.

- Truth is not what the majority believe. Majoritarianism says truth is what most people agree to. But the crowd can be wrong. Most Germans believed Hitler was right in the 30s and 40s. But they were clearly wrong. Truth is not based on majority vote. Indeed, truth can easily not be known by the majority.

What truth is:

- Truth is universal. Truth is something true for all people, for all places, for all times. Different cultures, different historical eras, different nationalities, do not change what truth is.

- Truth is absolute. It is not relative. An absolute is needed for standards. There can be no standards without absolutes. Indeed, there can be no measurement without absolutes. A builder knows that if he wants a number of pieces of lumber the same exact size, he will use one piece as the standard.

- Truth is objective. It is “independent of the knower and his consciousness” as Peter Kreeft and Ronald Tacelli put it. It is not based on subjective feelings or personal opinions. Truth does not reside in us or in our opinions. Personal experience is not the basis of truth. Truth is something that is external to us. We discover truth that already exists. We don’t make it up or create it.

- Truth corresponds with reality. It corresponds to the way things really are. Truth is what corresponds to the actual state of affairs being described. Truth is ‘telling it like it is’.

- Truth is based on God. God is the basis of truth. Only God provides an unchanging, universal reality upon which truth is based.

- Truth is personal. Truth is more than just abstract theories and propositions. Truth is something that demands a personal response. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew root usually translated true or truth means ‘something which can be relied upon’ or ‘someone who can be trusted’ as Alister McGrath notes.

- Truth is knowable. We may not know truth exhaustively, but we can know true truth. God has made us and the world in such a way that truth can be known. That is, while the finite can never grasp the infinite, if the infinite takes the initiative and reaches out to the finite, then that infinite truth can be known to some extent.

Note:

I disagree with Norman Geisler. God does not exist so God cannot be the basis of truth. There is no absolute truth because our brain is the final arbiter of truth.

______

______

Proof vis-à-vis truth:

A proof is sufficient evidence or a sufficient argument for the truth of a proposition. The concept applies in a variety of disciplines, with both the nature of the evidence or justification and the criteria for sufficiency being area-dependent. In the area of oral and written communication such as conversation, dialog, rhetoric, etc., a proof is a persuasive perlocutionary speech act, which demonstrates the truth of a proposition. In any area of mathematics defined by its assumptions or axioms, a proof is an argument establishing a theorem of that area via accepted rules of inference starting from those axioms and from other previously established theorems. The subject of logic, in particular proof theory, formalizes and studies the notion of formal proof. In some areas of epistemology and theology, the notion of justification plays approximately the role of proof, while in jurisprudence the corresponding term is evidence, with “burden of proof” as a concept common to both philosophy and law. In most disciplines, evidence is required to prove something. Evidence is drawn from experience of the world around us, with science obtaining its evidence from nature, law obtaining its evidence from witnesses and forensic investigation, and so on. A notable exception is mathematics, whose proofs are drawn from a mathematical world begun with axioms and further developed and enriched by theorems proved earlier.

_

From flat earth to spherical earth:

Today, we know the Earth is round. There’s no doubt about it. If someone tried to say otherwise, we would all laugh. But that wasn’t always the case. It took a long time for this idea to become cemented as common knowledge. In ancient Egyptian, Mediterranean and Indian cultures, it was believed that the Earth was a flat disc surrounded by oceans located at the centre of the Universe. Nordic cultures believed the Earth was flat and surrounded by oceans as well, with a world tree (Yggdrasill) was in the center. Ancient China subscribed to the theory that the Earth was flat and square, while the heavens were round. Many pre-Socratic Greek philosophers believed the Earth was flat. Some, such as Anaximander, thought the Earth was a round cylinder with a flat top. Anaximenes believed the Earth was flat and rode on the air, similar to how the Sun, Moon, and other heavenly bodies were flat and rode the air. In sixth century BC, Greek philosopher Pythagoras claimed the Earth was round, although most philosophers remained sceptical. A few hundred years later, Aristotle studied the skies and remarked in his writings De caelo that stars were seen in Egypt and Cyprus, but not in the northerly regions. Based on this and his other observations of the stars and the Moon, he argued that the Earth was a sphere. By the fifth century, the idea of a spherical Earth became more accepted. There were still scholars that opposed this view, although they were in the minority. Even though the concept of a spherical Earth was largely accepted by the medieval period, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan proved it by organizing an expedition that resulted in the first circumnavigation of the Earth centuries later, in 1519.

_

Exactly what evidence is sufficient to prove something is also strongly area-dependent, usually with no absolute threshold of sufficiency at which evidence becomes proof. In law, the same evidence that may convince one jury may not persuade another. Aristotle used the observation that patterns of nature never display the machine-like uniformity of determinism as proof that chance is an inherent part of nature. On the other hand, Thomas Aquinas used the observation of the existence of rich patterns in nature as proof that nature is not ruled by chance.

______

______

Bitter truth:

The “bitter truth” is nearly always in the sense of the painful truth — an unpalatable or unpleasant truth — a hard-to-swallow truth (one that’s hard to accept). The “bitter” part comes from the sense of intolerable, unbearable or unendurable. The “bitter” also overlaps in sense with harsh or corrosive in tone. Words that are harsh or biting are generally unwelcomed, so a “bitter truth” is a truth that no one wants to face (“because the truth means responsibility: that’s why everyone dreads it”). We do not want to hurt people’s feelings. Honesty without love can be cruel. But dishonesty with love can be just as unkind. Truth is supposed to free man from a web of ignorance and deceit. Truth is supposed to equip one with knowledge and knowhow. Truth is supposed to be the bedrock of an association, a union, a bond and all that makes for superb understanding between two people or among people in a given society. The question then arises: how can a constant that is supposed to be the cement of understanding be bitter? How can something that is expected to give knowledge be considered bitter? Truth should not be considered bitter. What is bitter is falsehood. Lying, cheating, deceit, hypocrisy, and all layers of untruth are bitter. It, therefore, cannot and should not be truth that should be considered bitter or clothed in the toga of bitter leaf. I am aware that most people do not like to be told the truth about themselves, about their character, about their dressing, about their manners, and about their excesses. That is when the truth may be considered bitter to the ears of the person being told the truth of his personal worth. A drunkard may not want his wife or his friends refer to him as such. It sounds unpalatable to his ears to be called an irresponsible husband to the bottle. It is the blunt, unadulterated truth that leaves a bitter taste in his mouth. The singular example of saying it as it is should not be sufficient to brand truth as bitter. Society must embrace the truth, and in so doing change its attitude to and branding of truth.

_

______

Truth hurts:

As much as we say we detest people lying to us, most of us stretch the truth an average of three times during a 10-minute conversation. The reason most people give for telling little white lies is that it’s polite, and they themselves don’t always want to hear the truth if it’s disagreeable and painful. So, when does the truth hurt and when do we actually prefer a little alternative reality?

- Lying politician winning:

A recent study at the University of Wisconsin found that politicians who lie are longer winded than those who keep their statements brief. This study used linguistics software to analyze more than 500 statements already vetted as true or false. The New York Times fact-checked 70 statements by Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump and other 2016 candidates, and rated three-quarters of Trump’s statements as “Mostly False, False or ‘Pants on Fire’ (a claim that is not only inaccurate but also ridiculous). Donald Trump won election despite people knowing that majority of his statements are false.

- The Truth can ruin your Appetite:

A recent poll on the Zagat Survey’s website asked restaurant goers if they like to see nutritional information on menus, and over 68 percent said, “No thanks!” As CEO Tim Zagat explains, “Many people dine out for entertainment and pleasure; therefore, they are less inclined to calorie count or obsess over the nutritional information. Patrons who are health conscious are already aware of what dishes are in line with their diets.”

- If you love me, you’ll lie to me:

“Children receive mixed messages in this society—we punish them for lying but tell them it’s rude to say they don’t like a Christmas gift,” says Bella DePaulo, Ph.D., who headed a study on liars at the University of Virginia, in which college students reported lying to their parents at least 50 percent of the time. “The result,” she says, “is that they grow up lying to us and justify it by saying it’s to spare our feelings.”

- Falling in love with Lies:

Not only do people routinely lie to each other when dating but, surprisingly, many people accept deception as a routine part of the courting ritual. DePaulo surveyed 147 people age 18 to 71 and found that 100 percent of dating couples copped to lying to their beloved at least a third of the time. Feldman, who has also studied deception between the sexes, found that women fib more often than men because they don’t want to hurt the other person’s feelings, while men are more likely to be stretching the truth to make themselves look better.

_

Why does the truth hurt?

- We fear accountability. If we commit to truth we will face both the opportunity for rejection and failure. Living in grey areas makes it easier to shrug off challenges.

- We fear conflict. People avoid direct conversation because we lie to be liked… I mean we like to be liked. That’s right; we lie to be liked because we like to be liked. Does that mean you intentionally speak falsehoods? No. More likely you accept falsehood and fail to call them out. Because to call someone out means they may reject you, or worse yet, attack you personally – because if you can’t discredit the facts you can attempt to discredit the speaker.

- We probably don’t care enough. We don’t care enough about the truth or about telling it. An “it’s all good” or “everything’s relative” attitude is pervasive and ignorant to the reality that there are absolutes and rights/wrongs. Likewise, if we don’t care about truth we won’t care about telling it.

______

_____

How to tell truth when it hurts:

Sometimes it can be difficult to tell the truth. Telling a hard truth can mean many different things, from that awkward moment when you let a friend know their zipper’s undone, to telling a romantic partner that you’re having issues with the relationship. Be it significant other, friend, coworker, or family member, telling someone the truth is generally the right decision. It leads to open and honest communication about how to move forward in a constructive way. Though it may seem scary, using kind language, exhibiting empathy, and being open minded will help you get through a hard conversation with grace.

_

Handle the Truth about Yourself:

Here are few things to keep in mind when you hear the truth about yourself.

- When you hear the truth about yourself, expect your brain to defend, rationalize, melt down, flip out, and push back. Be aware that your first response will often be the worst one, and work through it. Because it hurts to hear the truth, our brains are automatically going to defend, even if those defenses are exactly what got us here. The second your friend tells you a hard thing, the limbic system (emotions and drives) perceives a threat and takes over and initiates a fight-or-flight response, while your frontal cortex (reason and judgment) literally shuts down. It takes a huge self-awareness to understand the mental processes when we face criticism.

- When you hear the truth about yourself, the person who tells you the truth isn’t perfect and probably won’t say it perfectly, but that’s no excuse not to consider their words. The temptation when we hear criticism is to use the Mirror Defense, which is saying, “Well, what about you?” We want to discredit the source of the truth, so we drag up old history and the other person’s weaknesses for self-preservation. Or we say, “I don’t like your tone” and use their voice against them. The problem is, two wrongs can never make a right. In other words, someone else’s bad thing doesn’t cancel my bad thing. Even if the other person is a hypocrite, it doesn’t magically erase my own hypocrisy. And no one in the history of accountability has ever used perfect intonation and the perfect wording to tell the hard truth.

- When you hear the truth about yourself, instead of fighting back or shutting down, ask specific questions about how to move forward.

____

____

Should doctors tell the truth?

Should physicians not tell the truth to patients in order to relieve their fears and anxieties? This may seem simple but really it is a hard question. Not telling the truth may take many forms, has many purposes, and leads to many different consequences. Questions about truth and untruth in fact pervade all human communication. They are raised in families, clubs, work places, churches, and certainly in the doctor/patient relationship. In each context, the questions are somewhat differently configured. Not telling the truth in the doctor-patient relationship requires special attention because patients today, more than ever, experience serious harm if they are lied to. Not only is patient autonomy undermined but patients who are not told the truth about an intervention experience a loss of that all-important trust which is required for healing. Honesty matters to patients. They need it because they are ill, vulnerable, and burdened with pressing questions which require truthful answers.

_

Subtleties about truth-telling are embedded in complex clinical contexts. The complexities of modern medicine are such that honesty or truth, in the sense of simply telling another person what one believes, is an oversimplification. There are limits to what a doctor or nurse can disclose. Doctors and nurses have duties to others besides their patients; their professions, public health law, science, to mention just a few. They also have obligations created by institutional policies, contractual arrangements, and their own family commitments. The many moral obligations a nurse or physician may have to persons and groups other than to the patient complicates the question of just how much a professional should disclose to his or her patients. Doctors and nurses in some cultures believe that it is not wrong to lie about a bad diagnosis or prognosis. Certainly this is a difficult truth to tell but on balance, there are many benefits to telling the truth and many reasons not to tell a lie.

_

Lying in a clinical context is wrong for many reasons but less than full disclosure may be morally justifiable. If a patient is depressed and irrational and suicidal, then caution is required lest full disclosure contribute to grave harm. If a patient is overly pessimistic, disclosure of negative possibilities may actually contribute to actualizing these very possibilities. Now that so many medical interventions are available it is obviously wrong not to disclose the truth to a patient when the motive is to justify continued intervention or in order to cover up for one’s own failures for your benefit, not the benefit of the patient. Doctors and nurses, however, can do as much harm by cold and crude truth-telling as they can by cold and cruel withholding of the truth. To tell the truth in the clinical context requires compassion, intelligence, sensitivity, and a commitment to staying with the patient after the truth has been revealed.

_

Genetic testing:

In 2006 in California, Anne Wojcicki co-founded the personal genetics company with the mission of ‘helping people access, understand and benefit from the human genome’. For around $100 and a saliva sample, anyone can receive detailed information about their ancestry. If you live in the UK, you also get a range of health information, including genetic risks. Better genetic information certainly has huge potential to help people optimise their health and live longer. Knowing you’re at increased risk of certain diseases gives you the option of taking steps to reduce that risk. In 2013, when the actress Angelina Jolie found out she had the BRCA1 gene and an estimated 87 per cent chance of developing breast cancer at some point over her life, she opted to have a preventative double mastectomy – reducing her risk to 5 per cent. Jolie clearly felt that this information made her much better off. But more genetic information isn’t always better. Unlike for breast cancer, there are no clear preventative measures you can take if you find out you have a high risk of developing Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. If that knowledge is going to be a dark cloud over your life, you might reasonably prefer not to know. Information about biological relatives has helped to reunite families, but it has also torn them apart. When ‘George Doe’ (an alias) gave his parents the ‘gift’ of genetic testing, he found out that he had a half-brother that no one else in his family knew about. His ‘gift’ to his parents turned out to be a divorce.

_

Every patient needs an explanation of his illness that will be understandable and convincing to him if he is to cooperate in his treatment or be relieved of the burden of unknown fears. This is true whether it is a question of giving a diagnosis in a hopeful situation or of confirming a poor prognosis. The fact that a patient does not ask does not mean that he has no questions. One visit or talk is rarely enough. It is only by waiting and listening that we can gain an idea of what we should be saying. Silences and gaps are often more revealing than words as we try to learn what a patient is facing as he travels along the constantly changing journey of his illness and his thoughts about it. The main argument against a policy of deliberate, invariable denial of unpleasant facts is that it makes such communication extremely difficult, if not impossible. Once the possibility of talking frankly with a patient has been admitted, it does not mean that this will always take place, but the whole atmosphere is changed. We are then free to wait quietly for clues from each patient, seeing them as individuals from whom we can expect intelligence, courage, and individual decisions. They will feel secure enough to give us these clues when they wish. Finally, to tell the truth is not to deny hope. Hope and truth and even friendship and love are all part of an ethics of caring to the end.

_______

_______

Truth or Happiness:

A study found that students slightly favor Happiness to Truth. Specifically, about 58% of the students choose “Happiness,” and the rest (about 42%) choose “Truth.” At first blush, this result might appear to contradict what the happiness researchers say, namely, that happiness is everyone’s most important goal. It would seem that quite a few people are more interested in knowing the Truth than in being Happy. However, such a conclusion is not necessarily valid. In other studies, authors first put participants in a happy or sad mood. Then, they asked participants to read an essay about the effects of caffeine consumption. The essay highlighted both positive effects of caffeine consumption (“caffeine promotes mental alertness,” “caffeine can help avert Alzheimer’s,” etc.) as well as negative effects (“caffeine makes you nervous and jittery,” “caffeine can cause cancer,” etc.). What they wanted to test was this: Would peoples’ mood-state make a difference to their receptivity to the negative information about caffeine? Specifically, would happy or sad participants be more willing to process negative information about caffeine? The findings revealed that participants’ mood did make a difference to their receptivity to negative information: Participants in a positive mood were more likely to process negative effects of caffeine consumption. Participants in a negative mood, on the other hand, were much more likely to process positive information about caffeine. These results suggest that participants in a negative mood were much more interested in “repairing” their mood (i.e., becoming more “happy”), whereas those in a positive mood were more receptive to the “truth” (in this case, about the effects of caffeine consumption). These results have important implications for the circumstances under which people are like to choose Truth over Happiness. Specifically, it suggests that people may be more willing to seek Truth only if they are feeling sufficiently happy and not otherwise. This, in fact, turned out to be the case with students as well: those who chose Truth were, at the time of making the choice, less stressed out and more happy than those who chose Happiness. What this suggests is that there is a hierarchy to the order in which people seek Happiness vs. Truth: Happiness is sought first, and only after a “critical level” of happiness has been achieved does one have an appetite for Truth. In other words, Happiness does seem to be a more important goal than is the Truth for most people, but, once Happiness is achieved; Truth-seeking becomes more important.

_______

_______

Truthlikeness:

Verisimilitude (or truthlikeness) is a philosophical concept that distinguishes between the relative and apparent (or seemingly so) truth and falsity of assertions and hypotheses. The problem of verisimilitude is the problem of articulating what it takes for one false theory to be closer to the truth than another false theory. This problem was central to the philosophy of Karl Popper, largely because Popper was among the first to affirm that truth is the aim of scientific inquiry while acknowledging that most of the greatest scientific theories in the history of science are, strictly speaking, false. If this long string of purportedly false theories is to constitute progress with respect to the goal of truth, then it must be at least possible for one false theory to be closer to the truth than others. Even if truth is problematic to define or explain, or even not really required, we still have the vague idea that some theories are better than others—closer to the truth, whatever it is, or less wrong. This is what we mean by truthlike, or stating the degree of truth rather than truth or falsity of a theory; in Popper’s terminology, as we saw previously, it is called verisimilitude. Consider the problem of discovering the temperature at which water boils at sea level, along with two estimates: 105 and 150 degrees Celsius. The propositions “the boiling point is 105 degrees” and “the boiling point is 150 degrees” are both false, but it seems that this doesn’t say enough; in fact, 105 is a better guess, and so to be preferred (we would think).

______

Truthiness:

Truthiness is the belief or assertion that a particular statement is true based on the intuition or perceptions of some individual or individuals, without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts. Truthiness can range from ignorant assertions of falsehoods to deliberate duplicity or propaganda intended to sway opinions. American television comedian Stephen Colbert coined the term truthiness in this meaning as the subject of a segment called “The Wørd” during the pilot episode of his political satire program The Colbert Report on October 17, 2005. By using this as part of his routine, Colbert satirized the misuse of appeal to emotion and “gut feeling” as a rhetorical device in contemporaneous socio-political discourse. He particularly applied it to U.S. President George W. Bush’s nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court and the decision to invade Iraq in 2003. According to Colbert, while truthiness refers to statements that feel true but are actually false, “trumpiness” does not even have to feel true, much less be true. As evidence that Trump’s remarks exhibit this quality, he cited a Washington Post column stating that many Trump supporters did not believe his “wildest promises” but supported him anyway. Truthiness, Merriam-Webster’s 2006 word of the year, is “the quality of seeming to be true according to one’s intuition…without regard to logic [or] factual evidence.”

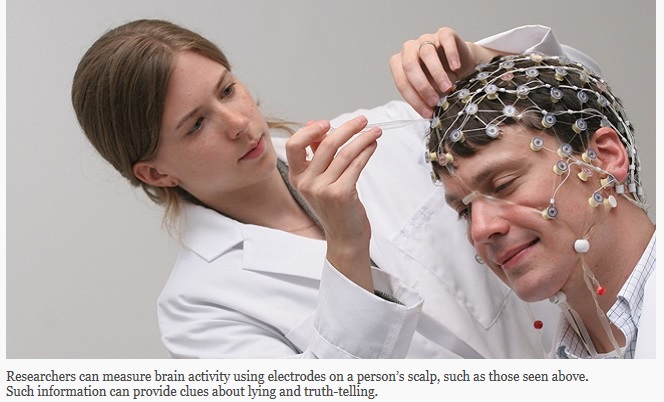

_