Dr Rajiv Desai

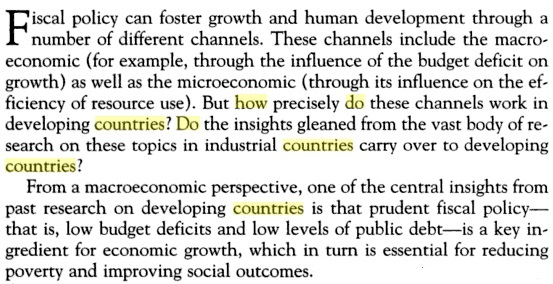

An Educational Blog

Development of Nation

Development of Nation:

_____

_____

Prologue:

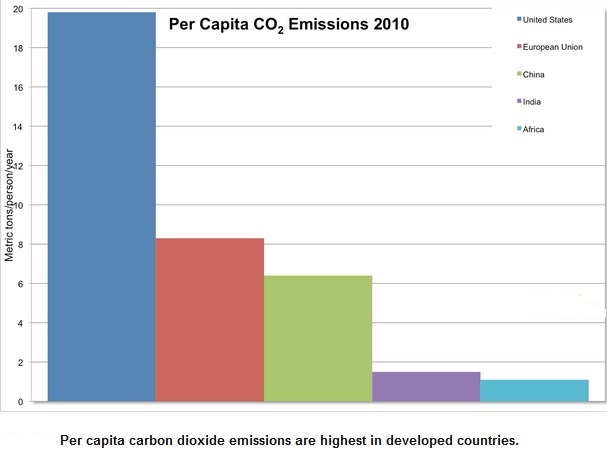

When evolution of human species occurred, all humans all over the world were same. Most people have lost sight of the fact that a short time ago—very short in terms of the life span of the earth—people were nomadic food gatherers, garnering an existence as best they could from what nature threw their way. It has been only about 10,000 years since the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution, when people changed from food gatherers to food producers. Throughout most of subsequent human history, civilizations have been based on a comfortable life for a privileged minority and unremitting toil for the vast majority. Only within the past two centuries, ordinary people are able to expect leisure and high consumption standards, and that only in the world’s economically developed countries. The total major countries of the world are 188 out of which only 32 are developed and remaining 156 are developing. But why developed nations have higher standard of living, better health care, better education and better care of handicapped and elderly? Is it because people of developed nation are more intelligent and more hard-working? Is it because of geography, culture, policies, resources and colonisation? I attempt to answer these questions knowing fully well that I am a student of science and not economics.

_____

Abbreviations and synonyms:

GDP = gross domestic product

GNP = gross national product

GNI = gross national income

LEDC = less economically developed country

LDC = least developed country

MEDC = more economically developed country

MDC = more developed country

NIC = newly industrialised country

LLDC = landlocked developing countries

OECD = organization of economic cooperation and development

HDI = human development index

______

______

What is development?

Does development mean human development, economic development or economic development giving rise to human development?

_

Human development:

The definition of development is fundamental to the comparison of developed and developing countries. The United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) annual Human Development Report (HDR) defines human development as, “the expansion of people’s freedoms and capabilities to lead lives that they value and have reason to value. It is about expanding choices. Freedoms and capabilities are a more expansive notion than basic needs.” In other words, people in developing countries strive to move up the ladder of development in order both to meet basic needs and to have the opportunity to lead richer, more fulfilling lives. It is worth noting that this definition aligns development with more choice and may not be directly comparable to well-being or happiness, which can depend on social relationships and a variety of other factors. Human development – or the human development approach – is about expanding the richness of human life, rather than simply the richness of the economy in which human beings live. It is an approach that is focused on people and their opportunities and choices.

People:

Human development focuses on improving the lives people lead rather than assuming that economic growth will lead, automatically, to greater wellbeing for all. Income growth is seen as a means to development, rather than an end in itself.

Opportunities:

Human development is about giving people more freedom to live lives they value. In effect this means developing people’s abilities and giving them a chance to use them. For example, educating a girl would build her skills, but it is of little use if she is denied access to jobs, or does not have the right skills for the local labour market. Three foundations for human development are to live a long, healthy and creative life, to be knowledgeable, and to have access to resources needed for a decent standard of living. Once the basics of human development are achieved, they open up opportunities for progress in other aspects of life.

Choice:

Human development is, fundamentally, about more choice. It is about providing people with opportunities, not insisting that they make use of them. No one can guarantee human happiness, and the choices people make are their own concern. The process of development – human development – should at least create an environment for people, individually and collectively, to develop to their full potential and to have a reasonable chance of leading productive and creative lives that they value.

The human development approach remains useful to articulating the objectives of development and improving people’s well-being by ensuring an equitable, sustainable and stable planet.

_

Development is a process where nations achieve higher standards of living, happiness and fulfilment often through economic growth. Development refers to developing countries working their up way up the ladder of economic performance, living standards, sustainability and equality that differentiates them from so-called developed countries. The point at which developing countries become “developed” comes down to a judgment call or statistical line in the sand that is often based on a combination of development indicators. Development is a concept that is difficult to define; it is inevitable that it will also be challenging to construct development taxonomy. Countries are placed into groups to try to better understand their social and economic outcomes. The most widely accepted criterion is labelling countries as either developed or developing countries. There is no generally accepted criterion that explains the rationale of classifying countries according to their level of development. This might be due to the diversity of development outcomes across countries, and the restrictive challenge of adequately classifying every country into two categories.

_

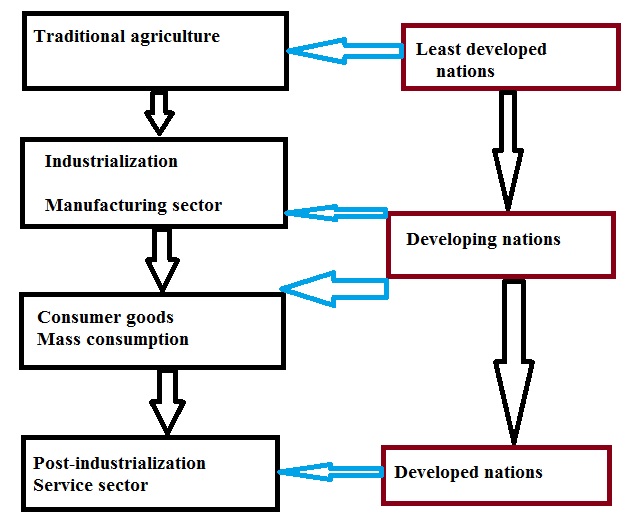

Economic development:

Economic development is a process whereby simple, low-income national economies are transformed into modern industrial economies. Although the term is sometimes used as a synonym for economic growth, generally it is employed to describe a change in a country’s economy involving qualitative as well as quantitative improvements. The theory of economic development—how primitive and poor economies can evolve into sophisticated and relatively prosperous ones—is of critical importance to underdeveloped countries, and it is usually in this context that the issues of economic development are discussed. Economic development first became a major concern after World War II. As the era of European colonialism ended, many former colonies and other countries with low living standards came to be termed underdeveloped countries, to contrast their economies with those of the developed countries, which were understood to be Canada, the United States, those of western Europe, most eastern European countries, the then Soviet Union, Japan, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As living standards in most poor countries began to rise in subsequent decades, they were renamed the developing countries.

_

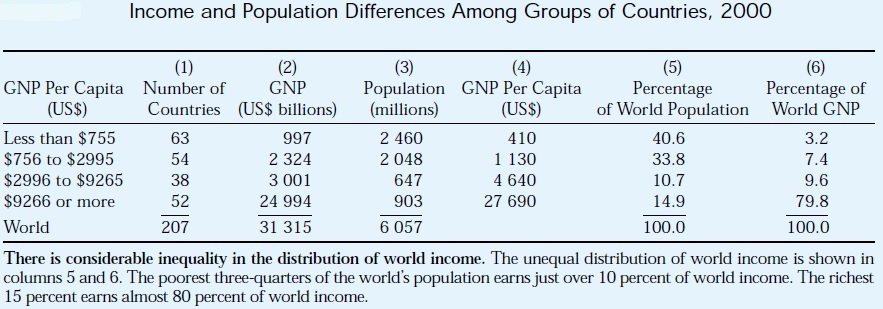

There is no universally accepted definition of what a developing country is; neither is there one of what constitutes the process of economic development. Developing countries are usually categorized by a per capita income criterion, and economic development is usually thought to occur as per capita incomes rise. A country’s per capita income (which is almost synonymous with per capita output) is the best available measure of the value of the goods and services available, per person, to the society per year. Although there are a number of problems of measurement of both the level of per capita income and its rate of growth, these two indicators are the best available to provide estimates of the level of economic well-being within a country and of its economic growth. The economic development of a country or society is usually associated with (amongst other things) rising incomes and related increases in consumption, savings, and investment. Of course, there is far more to economic development than income growth; for if income distribution is highly skewed, growth may not be accompanied by much progress towards the goals that are usually associated with economic development.

_

Economic development as an objective of policy:

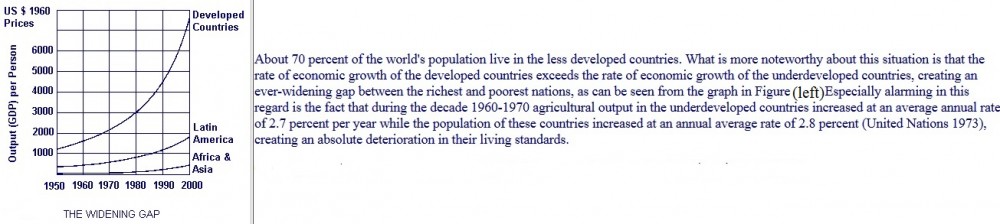

The field of development economics is concerned with the causes of underdevelopment and with policies that may accelerate the rate of growth of per capita income. While these two concerns are related to each other, it is possible to devise policies that are likely to accelerate growth (through, for example, an analysis of the experiences of other developing countries) without fully understanding the causes of underdevelopment. Studies of both the causes of underdevelopment and of policies and actions that may accelerate development are undertaken for a variety of reasons. There are those who are concerned with the developing countries on humanitarian grounds; that is, with the problem of helping the people of these countries to attain certain minimum material standards of living in terms of such factors as food, clothing, shelter, and sanitation. For them, low per capita income is the measure of the problem of poverty in a material sense. The aim of economic development is to improve the material standards of living by raising the absolute level of per capita incomes. Raising per capita incomes is also a stated objective of policy of the governments of all developing countries. For policymakers and economists attempting to achieve their governments’ objectives, therefore, an understanding of economic development, especially in its policy dimensions, is important. Finally, there are those who are concerned with economic development either because they believe it is what people in developing countries want or because they believe that political stability can be assured only with satisfactory rates of economic growth. These motives are not mutually exclusive. Since World War II many industrial countries have extended foreign aid to developing countries for a combination of humanitarian and political reasons. Those who are concerned with political stability tend to see the low per capita incomes of the developing countries in relative terms; that is, in relation to the high per capita incomes of the developed countries. For them, even if a developing country is able to improve its material standards of living through a rise in the level of its per capita income, it may still be faced with the more intractable subjective problem of the discontent created by the widening gap in the relative levels between itself and the richer countries. (This effect arises simply from the operation of the arithmetic of growth on the large initial gap between the income levels of the developed and the underdeveloped countries. As an example, an underdeveloped country with a per capita income of $100 and a developed country with a per capita income of $1,000 may be considered. The initial gap in their incomes is $900. Let the incomes in both countries grow at 5 percent. After one year, the income of the underdeveloped country is $105, and the income of the developed country is $1,050. The gap has widened to $945. The income of the underdeveloped country would have to grow by 50 percent to maintain the same absolute gap of $900.) Although there was once in development economics a debate as to whether raising living standards or reducing the relative gap in living standards was the true desideratum of policy, experience during the 1960–80 period convinced most observers that developing countries could, with appropriate policies, achieve sufficiently high rates of growth both to raise their living standards fairly rapidly and to begin closing the gap.

_

Harvard’s Lant Pritchett usefully defines development as a four-fold process of modernization, culminating in the following conditions in each:

1. Economic: An economy characterized by high levels of productivity, typically dominated by large corporations with professional management.

2. Political: A polity in which the citizens collectively constitute the state, which in turn exists legitimately only as an expression of their will. It ensures universal equal treatment to all citizens by the state.

3. Administrative: State functions are administered by a civil service bureaucracy characterized by merit-based recruitment, tenure in office not linked to personal or political patron, hierarchical structures, and performance through an impersonal application of rules.

4. Social: All citizens perceive themselves and other citizens as members of a national community.

________

________

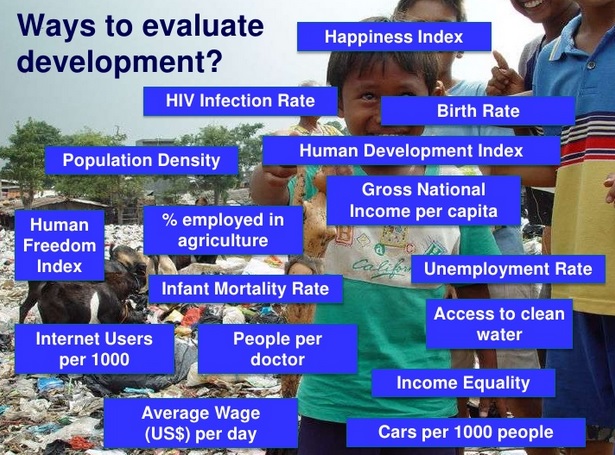

Development indicators and its correlations:

Geographers use a series of development indicators to compare the development of one region against another. Geographers compare the statistics for different countries to see if there is a relationship or correlation between the data for different countries. A correlation helps to show what factors contribute to development. There is no single way to calculate the level of development because of the variety of economies, cultures and peoples.

_

Measuring development:

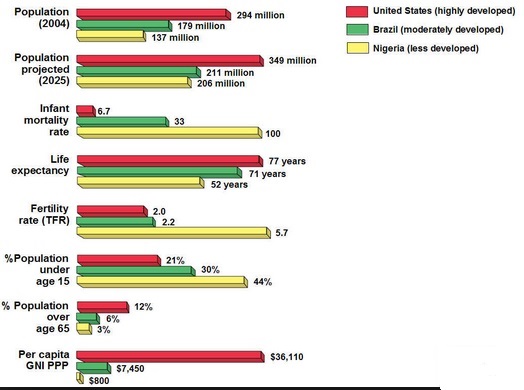

Studying development is about measuring how developed one country is compared to other countries or to the same country in the past. Development measures show how economically, socially, culturally or technologically advanced a country is. The two most important ways of measuring development are economic development and human development.

•Economic development is a measure of a country’s wealth and how it is generated (for example agriculture is considered less economically advanced than banking).

•Human development measures the access the population has to wealth, jobs, education, nutrition, health, leisure and safety – as well as political and cultural freedom. Material elements, such as wealth and nutrition, are described as the standard of living. Health and leisure are often referred to as quality of life.

_

Economic development indicators:

To assess the economic development of a country, geographers use economic indicators including:

•Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the total value of goods and services produced by a country in a year.

•Gross National Product (GNP) measures the total economic output of a country, including earnings from foreign investments.

•GNP per capita is a country’s GNP divided by its population. (Per capita means per person.)

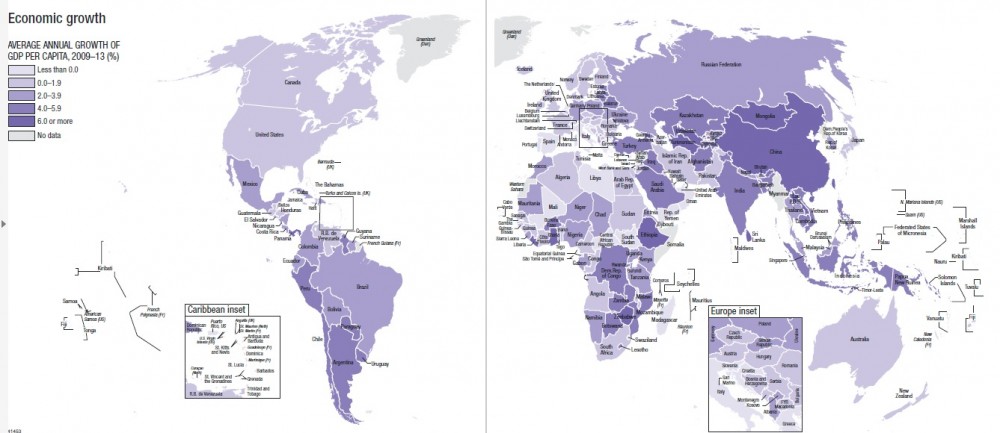

•Economic growth measures the annual increase in GDP, GNP, GDP per capita, or GNP per capita.

•Inequality of wealth is the gap in income between a country’s richest and poorest people. It can be measured in many ways, (e.g. the proportion of a country’s wealth owned by the richest 10 per cent of the population, compared with the proportion owned by the remaining 90 per cent).

•Inflation measures how much the prices of goods, services and wages increase each year. High inflation (above a few percent) can be a bad thing, and suggests a government lacks control over the economy.

•Unemployment is the number of people who cannot find work.

•Economic structure shows the division of a country’s economy between primary, secondary and tertiary industries.

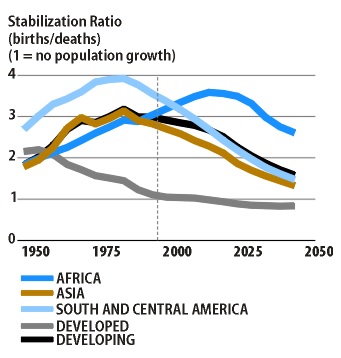

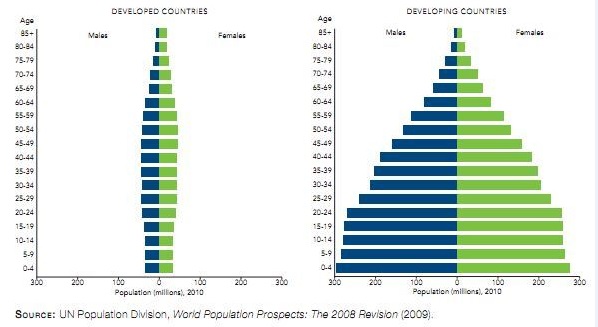

•Demographics study population growth and structure. It compares birth rates to death rates, life expectancy and urban and rural ratios. Many LEDCs have a younger, faster-growing population than MEDCs, with more people living in the countryside than in towns. The birth rate in the UK is 11 per 1,000, whereas in Kenya it is 40.

_

Human development indicators:

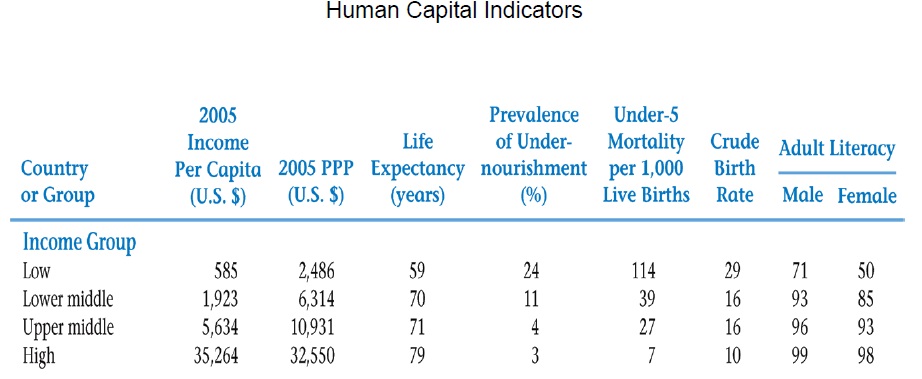

Development often takes place in an uneven way. A country may have a very high GDP – derived, for example, from the exploitation of rich oil reserves – while segments of the population live in poverty and lack access to basic education, health and decent housing. Hence the importance of human development indicators measuring the non-economic aspects of a country’s development.

Human development indicators include:

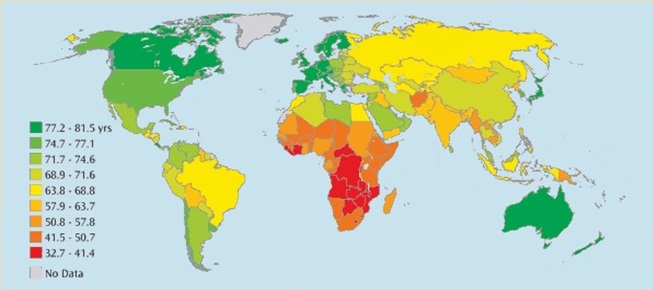

•Life expectancy – the average age to which a person lives, e.g. this is 79 in the UK and 48 in Kenya.

_

The figure below shows life expectancy worldwide. In general, developed nations have higher life expectancy than developing nations.

_

•Infant mortality rate – counts the number of babies, per 1000 live births, who die under the age of one. This is 5 in the UK and 61 in Kenya.

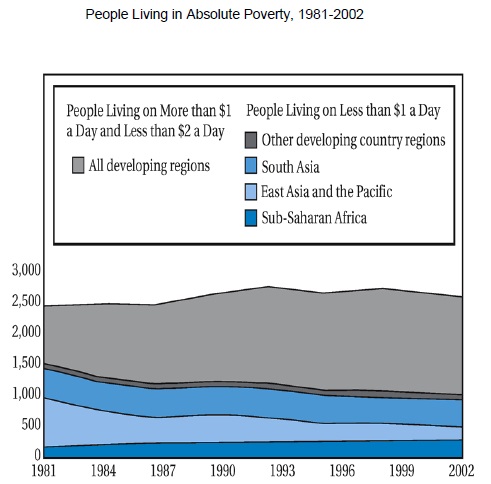

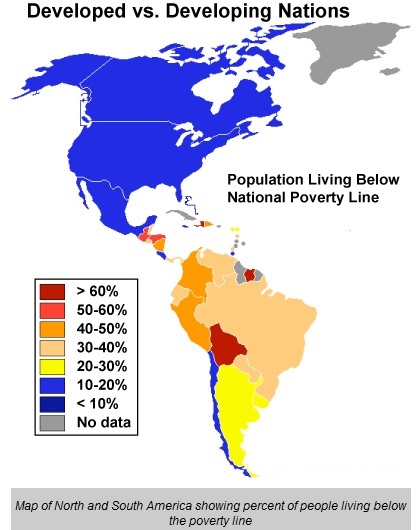

•Poverty – indices count the percentage of people living below the poverty level, or on very small incomes (e.g. under £1 per day).

•Access to basic services – the availability of services necessary for a healthy life, such as clean water and sanitation.

•Access to healthcare – takes into account statistics such as how many doctors there are for every patient.

•Risk of disease – calculates the percentage of people with diseases such as AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

•Access to education – measures how many people attend primary school, secondary school and higher education.

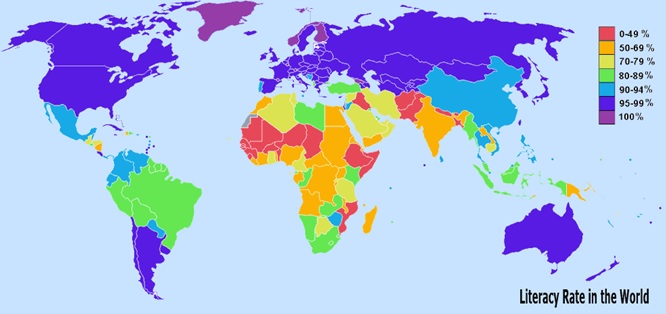

•Literacy rate – is the percentage of adults who can read and write. This is 99 per cent in the UK, 85 per cent in Kenya and 60 per cent in India.

•Access to technology – includes statistics such as the percentage of people with access to phones, mobile phones, television and the internet.

•Male/female equality – compares statistics such as the literacy rates and employment between the sexes.

•Government spending priorities – compares health and education expenditure with military expenditure and paying off debts.

_

Determining Development by the UN:

To determine a country’s development, these statistics are usually considered by the United Nations:

1. GDP (Gross Domestic Product)

2. Life Expectancy

3. Literacy Rate

4. Education

5. Healthcare System

_

Development Indicators can be qualitative and quantitative:

1. Quantitative Indicators – are based on objective and truthful pieces of information; and often collected in surveys or in a census.

2. Qualitative Indicators – are based on subjective feelings, impression and opinion. These provide a good indication of the social health of a country.

_

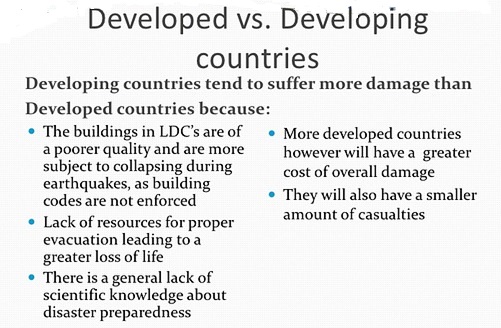

Comparing Levels of Development:

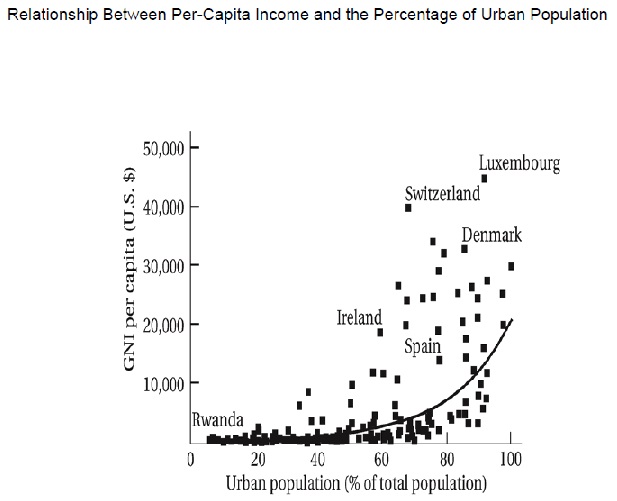

Countries are unequally endowed with natural resources. For example, some countries benefit from fertile agricultural soils, while others have to put a lot of effort into artificial soil amelioration. Some countries have discovered rich oil and gas deposits within their territories, while others have to import most “fossil” fuels. In the past a lack or wealth of natural resources made a big difference in countries’ development. But today a wealth of natural resources is not the most important determinant of development success. Consider such high-income countries as Japan or the Republic of Korea. Their high economic development allows them to use their limited natural wealth much more productively (efficiently) than would be possible in many less developed countries. The productivity with which countries use their productive resources – physical capital, human capital, and natural capital – is widely recognized as the main indicator of their level of economic development. Theoretically, then, economists comparing the development of different countries should calculate how productively they are using their capital. But such calculations are extremely challenging, primarily because of the difficulty of putting values on elements of natural and human capital. In practice economists use gross national product (GNP) per capita or gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for the same purpose. These statistical indicators are easier to calculate, provide a rough measure of the relative productivity with which different countries use their resources, and measure the relative material welfare in different countries, whether this welfare results from good fortune with respect to land and natural resources or from superior productivity in their use.

__

GDP, GNP and GNI:

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total market value of all goods and services produced in the country, in a given year or quarter. GDP is equal to all government, consumer, and investment spending, plus the value of exports, minus the value of imports. GDP includes earnings made by foreigners while inside the country. GDP does not include earnings by its residents while outside of the country.

_

Gross National Product (GNP) is the total market value of all goods and services produced by domestic residents. GNP includes domestic residents earnings from goods and services produced and sold abroad, and investments abroad. GNP does not include earnings by foreign residents while inside the country. GNP = GDP + Net property income from abroad. This net income from abroad includes, dividends , interest and profit. GNP includes the value of all goods and services produced by nationals whether in the country or not.

_

GNP measures the income of the people within the country whereas GDP measures economic activity in the country. If economic activity occurs in the country but the income from this activity accrues to foreigners, it will still be counted in GDP but not in GNP.

_

There are two ways of calculating GDP and GNP:

•By adding together all the incomes in the economy – wages, interest, profits, and rents.

•By adding together all the expenditures in the economy- consumption, investment, government purchases of goods and services, and net exports (exports minus imports).

In theory, the results of both calculations should be the same. Because one person’s expenditure is always another person’s income, the sum of expenditures must equal the sum of incomes. When the calculations include expenditures made or incomes received by a country’s citizens in their transactions with foreign countries, the result is GNP. When the calculations are made exclusive of expenditures or incomes that originated beyond a country’s boundaries, the result is GDP. GNP may be much less than GDP if much of the income from a country’s production flows to foreign persons or firms. For example, in 1994 Chile’s GNP was 5 percent smaller than its GDP. If a country’s citizens or firms hold large amounts of the stocks and bonds of other countries’ firms or governments, and receive income from them, GNP may be greater than GDP. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, GNP exceeded GDP by 7 percent in 1994. For most countries, however, these statistical indicators differ insignificantly.

_

Gross National Income (GNI) is GDP plus income paid into the country by other countries for such things as interest and dividends (less similar payments paid out to other countries). The World Bank define GNI as the sum of value added by all resident producers plus any product taxes (minus subsidies) not included in the valuation of output plus net receipts of primary income (compensation of employees and property income) from abroad. In this respect, GNI is quite similar to GNP, which measures output from the citizens and companies of a particular nation, regardless of whether they are located within its boundaries or overseas. The World Bank now uses GNI rather than GNP.

_

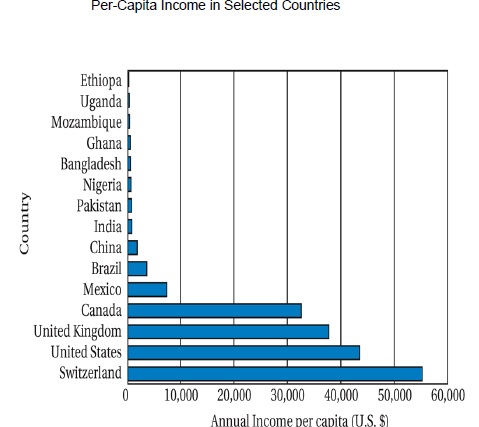

Per capita income:

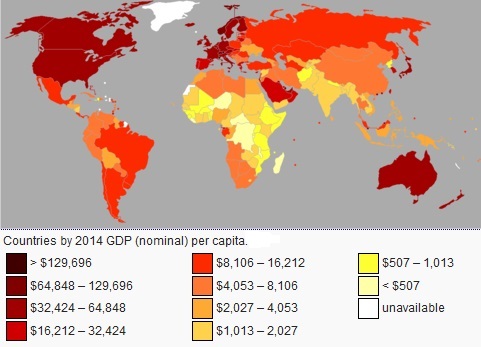

GDP and GNP can serve as indicators of the scale of a country’s economy. But to judge a country’s level of economic development, these indicators have to be divided by the country’s population. GDP per capita and GNP per capita show the approximate amount of goods and services that each person in a country would be able to buy in a year if incomes were divided equally. That is why these measures are also often called “per capita incomes.”

_

North America, Western Europe and Australia show highest GDP per capita.

_

Limitation of per capita income:

It’s important to remember that GDP and GNP are measures of the big picture of a nation’s economy. As a result, there are statistics closer to home that don’t match up with GDP/GNP, particular when we look at per capita figures.

1. Personal income.

Per Capita GDP in the US is $49,922 for 2012. This should not be confused with anything resembling average income! Per capita GDP is simply the GDP divided by the population of the country. It is not an average wage. According to the Social Security Administration, the average wage was closer to $43,000 in 2012.

2. Income distribution.

We can look at GDP/GNP numbers to determine the overall economic strength of a given nation, but that number does not indicate the income distribution within the country. A nation could have a relatively high GDP/GNP, or a high per capita GDP/GNP because it has a small number of very large industries (typical of oil producing countries). In this way, high GDP/GNP numbers could mask the fact that the majority of people in a country are relatively poor.

3. Living conditions:

Because per-capita income is the overall income of a population divided by the number of people included in the population, it does not always give an accurate representation of the quality of life due to the function’s inability to account for skewed data. For instance, if there is an area where 50 people are making $1 million per year and 1,000 people making $100 per year the per capita income is $47,714, but that does not give a true picture of the living conditions of the entire population.

_

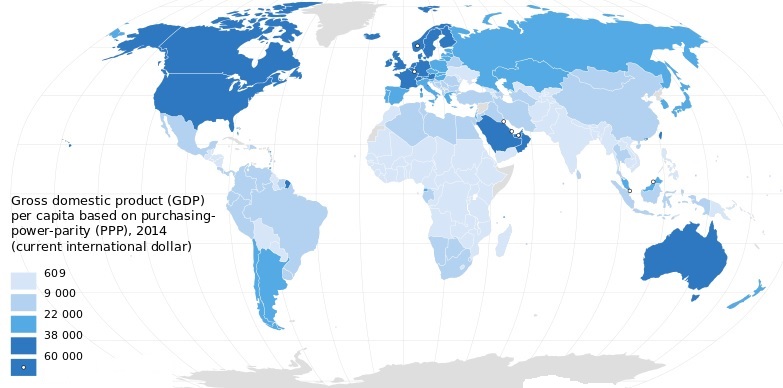

Nominal vs. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP):

The lack of comparable reporting from one country to another has given rise to two methods of computing either GDP or GNP, nominal and purchasing power parity, or PPP. Nominal is measuring the size of a nation’s economy on the basis of its economy in local currency, converted to dollars (typically). The conversion is based on currency exchange rates in the currency market. PPP ignores currency exchange rates, and measures the economy of countries based on the cost of a common basket of goods and services. The amount of goods and services one can purchase depends on two things: income and the price level. Same amount of income buys fewer goods and services if prices are high compared to the case when prices are low. This implies that if we ignore differences in price level across countries, then just the comparison of per-capita income across countries can give misleading picture of differences in the standards of living. It turns out that on average prices in developing countries are lower than prices in developed countries. One dollar spent in India buys more goods and services than in the United States. The main reason for lower prices in developing countries is relatively low labor cost. Researchers have tried to take into account such price differences across countries and developed the concept of purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP is calculated using a common set of international prices for all goods and services produced, valuing goods in all countries at U.S. prices. PPP is defined as the number of units of a foreign country’s currency required to purchase the identical quantity of goods and services in the local markets as $1 would buy in the United States. GNP in PPP terms thus provides a better comparison of average income or consumption between economies. In developing countries real GNP per capita is usually higher than nominal GNP per capita, while in developed countries it is often lower. Thus the gap between real per capita incomes in developed and developing countries is smaller than the gap between nominal per capita incomes.

_

Nominal and real GNP per capita in various countries, 1999

| GNP per capita (US Dollars) |

GNP per capita (PPP Dollars) |

|

| India China Russia Brasil USA Germany Japan |

340 620 2,245 3,640 26,980 27,510 39,640 |

1,400 2,920 4,480 5,400 26,980 20,070 22,110 |

_

_

North America, Western Europe, Australia and Gulf-states show highest GDP-PPP per capita.

_

_

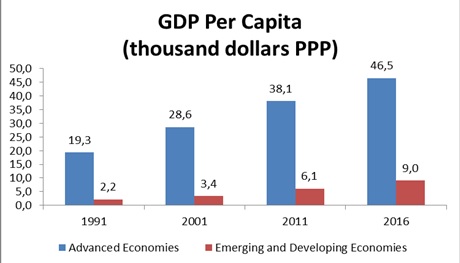

The figure above shows wide gap in GDP per capita between developed and developing nations over last three decades.

_

Limitations of GDP/GNP/GNI:

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the magical term often used to describe the economic growth of a country. Governments, experts and news reports point to it as a measure of progress. In development, a field often dominated by economists, GDP is all but an obligatory part of the discussion when it comes to country level progress. The problem is many other experts say GDP is actually not very good at measuring either progress or development. Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz is among the most vocal opponents of overusing GDP as a yardstick for development. He says that it does not capture equally important issues like poverty levels and inequality. The overall economies of countries can hum along for years showing solid GDP growth without meaningful change for the majority of its citizens. One need not look further than the US to see how middle class incomes have held steady over the past few decades, despite overall GDP growth and wealth accumulation at the top. Although they reflect the average incomes in a country, GNP per capita and GDP per capita have numerous limitations when it comes to measuring people’s actual well-being. They do not show how equitably a country’s income is distributed. They do not account for pollution, environmental degradation, and resource depletion. They do not register unpaid work done within the family and community, or work done in the shadow economy. And they attach equal importance to “goods” (such as medicines) and “bads” (cigarettes, chemical weapons) while ignoring the value of leisure and human freedom. Thus, to judge the relative quality of life in different countries, one should also take into account other indicators showing, for instance, the distribution of income and incidence of poverty, people’s health and longevity, access to education, the quality of the environment, and more. Experts also use composite statistical indicators of development.

_

Other limitations of GDP:

Non-market transactions – GDP excludes activities that are not provided through the market, such as household production and volunteer or unpaid services. As a result, GDP is understated.

Underground economy – Official GDP estimates may not take into account the underground economy, in which transactions contributing to production, such as illegal trade and tax-avoiding activities, are unreported, causing GDP to be underestimated.

Non-monetary economy – GDP omits economies where no money comes into play at all, resulting in inaccurate or abnormally low GDP figures.

Sustainability of growth – GDP does not measure the sustainability of growth. A country may achieve a temporarily high GDP by over-exploiting natural resources or by misallocating investment.

One main problem in estimating GDP growth over time is that the purchasing power of money varies in different proportion for different goods, so when the GDP figure is deflated over time, GDP growth can vary greatly depending on the basket of goods used and the relative proportions used to deflate the GDP figure

_

A development index measures a country’s performance according to specific development indicators. Some countries may appear to be developed according to some indices, but not according to others.

Vietnam and Pakistan:

Both countries have a similar per capita GDP. However, life expectancy and literacy are considerably higher in Vietnam than they are in Pakistan.

Saudi Arabia and Croatia:

Saudi Arabia has a per capita GDP comparable to that of Croatia. However, in Saudi Arabia there is greater inequality between men and women when considering access to education and political power. So, although they are equal on an economic development index – Saudi Arabia is less developed on a human development index.

_

Problems with indices:

Development indices can be misleading and need to be used with care. For example:

•Many indices are averages for the whole population of a country. This means that indices do not always reveal substantial inequalities between different segments of society. For example, a portion of the population of a highly developed country could be living below the poverty line.

•In some countries, the data used in indices could be out of date or hard to collect. Some countries do not wish to have certain index data collected – for example, many countries do not publish statistics about the number of immigrants and migrants.

To balance inaccuracies, indices tend to be an amalgamation of many different indicators. The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) is a weighted mix of indices that show life expectancy, knowledge (adult literacy and education) and standard of living (GDP per capita). As Vietnam has a higher literacy rate and life expectancy than Pakistan, it has much higher HDI value even though it has a similar per capita GDP.

_

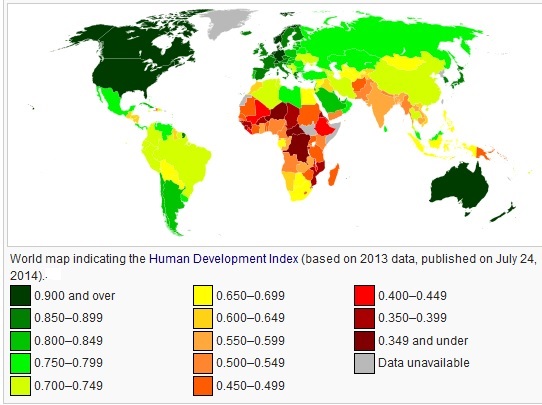

HDI:

The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) is probably the most widely recognized tool for measuring development and comparing the progress of developing countries. The HDI scores and ranks each country’s level of development based on three categories of development indicators: income, health and education. The Human Development Index is a composite statistics of life expectancy, education, and income per capita indicators, which are used to rank countries into four tiers of human development. The human development report (HDR) classifies countries into four levels of development based on their HDIs: “very high human development,” “high human development,” “medium human development” and “low human development.” Each level of development is generally accompanied by higher income, longer life expectancy and more years of education, which combine to provide people with more capabilities, freedoms and choices. Over half of the world’s population live in countries with “medium human development” (51%), while less than a fifth (18%) populate countries falling in the “low human development” category. Countries with “high” to “very high” human development account for slightly less than a third of the world’s total population (30%). From 2007 to 2010, the first category was referred to as developed countries, and the last three are all grouped in developing countries. The 2010 Human Development Report introduced an Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI). While the simple HDI remains useful, it stated that “the IHDI is the actual level of human development (accounting for inequality),” and “the HDI can be viewed as an index of ‘potential’ human development (or the maximum IHDI that could be achieved if there were no inequality).”. HDI is measured between 0 and 1. A HDI between 1 and 0.8 is considered high, 0.8 and 0.6 is considered medium and 0.6 to 0.4 is considered low. The USA has an HDI of 0.994 whereas Kenya has an HDI of 0.474.

_

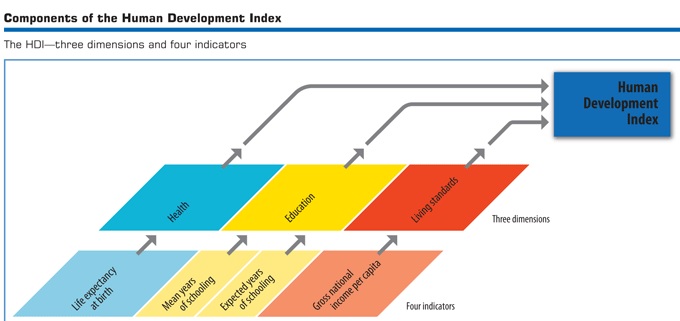

Human Development Report (HDR) combines three dimensions:

•A long and healthy life: Life expectancy at birth

•Education index: Mean years of schooling and Expected years of schooling

•A decent standard of living: GNI per capita (PPP US$)

_

What does the Human Development Index tell us?

The Human Development Index (HDI) was created to emphasize that expanding human choices should be the ultimate criteria for assessing development results. Economic growth is a mean to that process, but is not an end by itself. The HDI can also be used to question national policy choices, asking how two countries with the same level of GNI per capita can end up with different human development outcomes. For example, Malaysia has GNI per capita higher than Chile, but in Malaysia, life expectancy at birth is about 7 years shorter and expected years of schooling is 2.5 years shorter than Chile, resulting in Chile having a much higher HDI value than Malaysia. These striking contrasts can stimulate debate about government policy priorities.

_

Can GNI per capita be used to measure human development instead of the HDI?

No. Income is a means to human development, and not the end. The GNI per capita only reflects average national income. It does not reveal how that income is spent, nor whether it translates to better health, education and other human development outcomes. In fact, comparing the GNI per capita rankings and the HDI rankings of countries can reveal much about the results of national policy choices. Gabon with a GNI per capita of $16,367 (PPP$) has a GNI rank of 68, but an HDI rank 110 – the same as that of Indonesia whose GNI per capita is only $9,788 (PPP$).

_

Life expectancy at birth: Number of years a newborn infant could expect to live if prevailing patterns of age-specific mortality rates at the time of birth stay the same throughout the infant’s life.

Expected years of schooling: Number of years of schooling that a child of school entrance age can expect to receive if prevailing patterns of age-specific enrolment rates persist throughout the child’s life.

Mean years of schooling: Average number of years of education received by people ages 25 and older, converted from education attainment levels using official durations of each level.

_

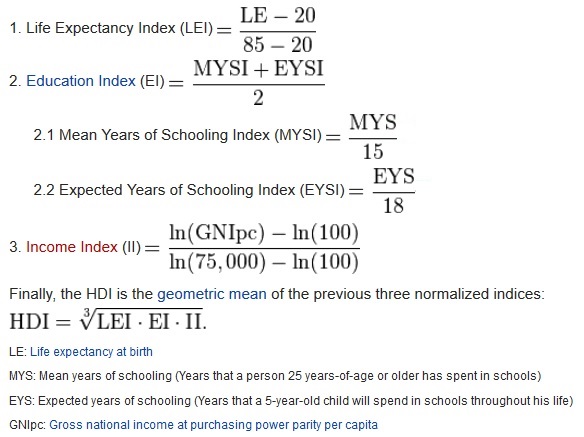

In its 2010 Human Development Report, the UNDP began using a new method of calculating the HDI. The following three indices are used:

_

The health dimension is assessed by life expectancy at birth component of the HDI is calculated using a minimum value of 20 years and maximum value of 85 years. The education component of the HDI is measured by mean of years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and expected years of schooling for children of school entering age. Expected years of schooling is capped at 18 years. The indicators are normalized using a minimum value of zero and maximum aspirational values of 15 and 18 years respectively. The two indices are combined into an education index using arithmetic mean. The standard of living dimension is measured by gross national income per capita. The goalpost for minimum income is $100 (PPP) and the maximum is $75,000 (PPP). The minimum value for GNI per capita, set at $100, is justified by the considerable amount of unmeasured subsistence and nonmarket production in economies close to the minimum that is not captured in the official data. The HDI uses the logarithm of income, to reflect the diminishing importance of income with increasing GNI. The scores for the three HDI dimension indices are then aggregated into a composite index using geometric mean. HDI ranges from a theoretical minimum of zero (for a life expectancy = 25 years, complete illiteracy and a GDP per capita = $100 at purchasing power parity) to a theoretical maximum of one (for a life expectancy = 85 years, 100% literacy and a GDP per capita = $40,000 at purchasing power parity). In practice, the observed range is 0.3 – 0.97. The HDI simplifies and captures only part of what human development entails. It does not reflect on inequalities, poverty, human security, empowerment, etc.

_

Why is geometric mean used for the HDI rather than the arithmetic mean?

In 2010, the geometric mean was introduced to compute the HDI. Poor performance in any dimension is directly reflected in the geometric mean. That is to say, a low achievement in one dimension is not anymore linearly compensated for by high achievement in another dimension. The geometric mean reduces the level of substitutability between dimensions and at the same time ensures that a 1 percent decline in index of, say, life expectancy has the same impact on the HDI as a 1 percent decline in education or income index. Thus, as a basis for comparisons of achievements, this method is also more respectful of the intrinsic differences across the dimensions than a simple average.

_

Why is the HDI using the logarithm of income component?

In addition to capping, the income enters the HDI as a logarithmically transformed variable. The idea is to emphasize diminishing marginal utility of transforming income into human capabilities. This means that the concave logarithmic transformation brings closer the notion that an increase of GNI per capita by $100 in a country where the average income is only $500 has a much greater impact on the standard of living than the same $100 increase in a country where the average income is $5,000 or $50,000.

_

HDI 2014:

_

Criticism of HDI:

The Human Development Index has been criticized on a number of grounds including alleged ideological biases towards egalitarianism and so-called “Western models of development”, failure to include any ecological considerations, lack of consideration of technological development or contributions to the human civilization, focusing exclusively on national performance and ranking, lack of attention to development from a global perspective, measurement error of the underlying statistics, and on the UNDP’s changes in formula which can lead to severe misclassification in the categorisation of ‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’ or ‘very high’ human development countries. Given its focus on basic education and health measures, the HDI is most relevant in countries with low or medium human development. Just as the Millennium Development Goals have been a galvanizing force for efforts to support the world’s poorest countries, the HDI is a useful benchmark for such countries. However, it lacks a broader set of measures to guide progress once basic levels of need have been addressed. As a result there is little variation in scores amongst high-income countries. Though the HDI covers 187 countries, the limited range of indicators mean that its descriptive and explanatory value is limited for upper middle and high income countries.

_

Can the HDI alone measure a country’s level of human development?

No. The concept of human development is much broader than what can be captured by the HDI, or by any other composite index in the Human Development Report (Inequality-adjusted HDI, Gender development index, Gender Inequality Index and Multidimensional Poverty Index). The composite indices are a focused measure of human development, zooming in on a few selected areas. A comprehensive assessment of human development requires analysis of other human development indicators and information presented in the statistical annex of the report (see the Readers guide to the Report).

_

Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI):

Like development, poverty is multidimensional — but this is traditionally ignored by headline money metric measures of poverty. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), published for the first time in the 2010 Report, complements monetary measures of poverty by considering overlapping deprivations suffered at the same time. The index identifies deprivations across the same three dimensions as the HDI and shows the number of people who are multi-dimensionally poor (suffering deprivations in 33% or more of weighted indicators) and the number of deprivations with which poor households typically contend with. It can be deconstructed by region, ethnicity and other groupings as well as by dimension, making it an apt tool for policymakers. The MPI can help the effective allocation of resources by making possible the targeting of those with the greatest intensity of poverty; it can help address MDGs strategically and monitor impacts of policy intervention. The MPI can be adapted to the national level using indicators and weights that make sense for the region or the country, it can also be adopted for national poverty eradication programs, and it can be used to study changes over time. Almost 1.5 billion people in the 101 developing countries covered by the MPI—about 29 percent of their population — live in multidimensional poverty — that is, with at least 33 percent of the indicators reflecting acute deprivation in health, education and standard of living. And close to 900 million people are vulnerable to fall into poverty if setbacks occur – financial, natural or otherwise.

_

GDP vs. HDI:

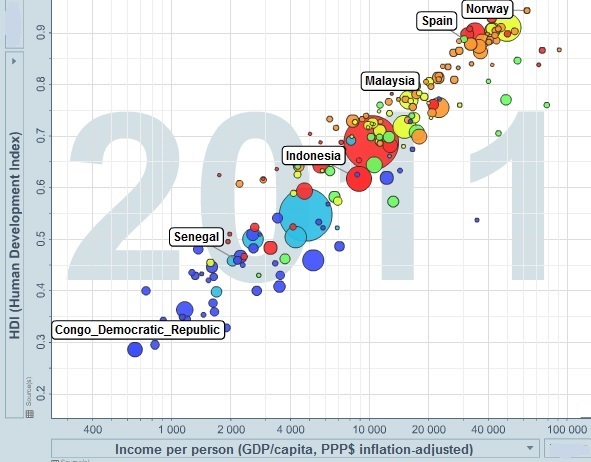

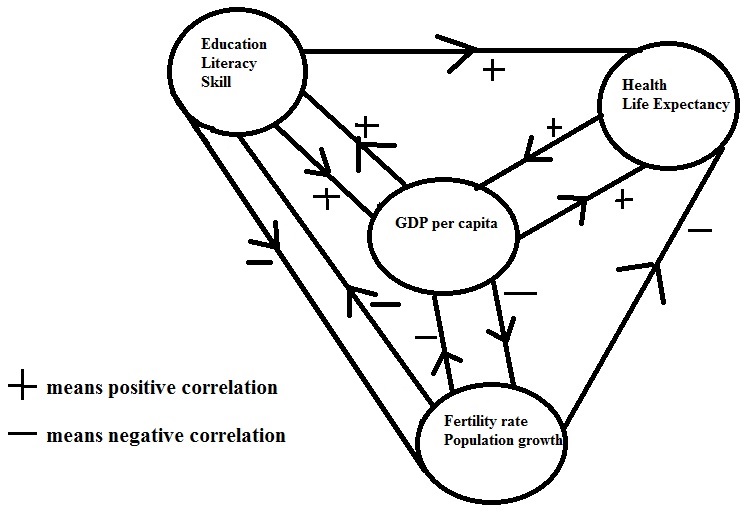

While GDP and HDI may seem different with HDI being considered more advanced than GDP, which it technically is, GDP and HDI according to Hans Rosling are actually quite similar and tell similar results. In his own words: “There is today a very strong correlation between GDP/capita and HDI as seen from the graph above. If you exclude 6 countries on the right side of the strong correlation that have higher GDP/capita than HDI due to oil or diamonds; and if you exclude 6 former Soviet Republics with collapsed economy but still high literacy rate on the left side of the correlation; you will find that the GDP/capita and the value on Human Development Index follow each other very closely from the worst-off country Congo to the best-off country Norway. The reason seems to be that nations today are surprisingly capable in converting the available national income (measured as GDP/capita) into a longer lifespan for the people (measured as Life expectancy at birth) and into access to education (measured by mean of years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and expected years of schooling for children of school entering age). But the reason may also be that nations today are very good at converting improved health and education into economic growth. Most probably the causality goes in both directions. If you want better health and education fix economic growth. If you want faster economic growth provide better education and health service. GDP/capita appears to be as good a measure of progress of nations as are HDI. This is because with high GDP, the government and the people have more money to spend on education and health care. Vice versa, with better education and health service comes faster economic growth, because now people are healthier meaning more likely to work and as they have better education they are more likely to further themselves in their field earning more money. But, the analysis for different income group of countries suggests that the positive relationship between GDP and HDI is more prominent for the low income countries and weakens for the middle and high income countries in all the years.

_

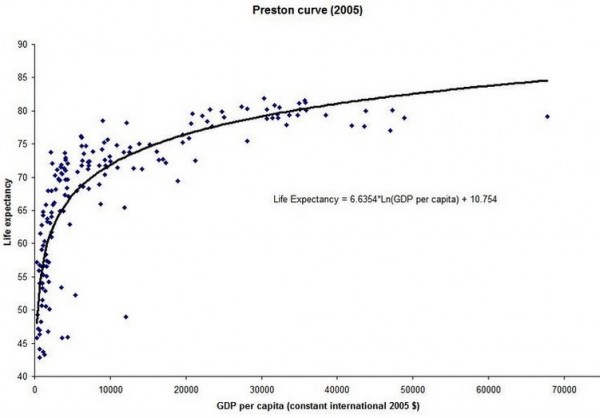

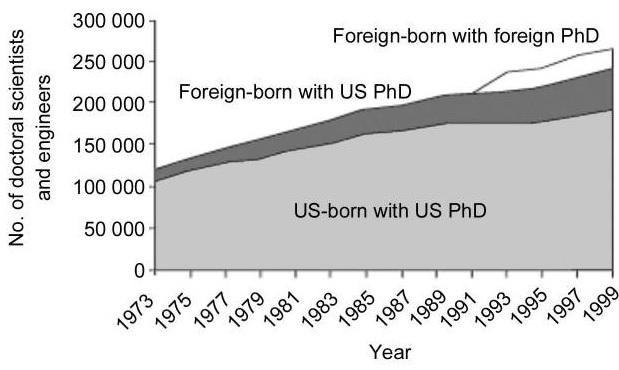

Economic Growth and Life Expectancy:

The relationship between income and life expectancy has been demonstrated by a number of statistical studies. The so-called Preston curve, for example, indicates that individuals born in wealthier countries, on average, can expect to live longer than those born in poor countries. It is not the aggregate growth in income, however, that matters most, but the reduction in poverty. The most obvious explanation behind the connection between life expectancy and income is the effect of food supply on mortality. Historically, there have been statistically convincing parallels between prices of food and mortality. Higher income also implies better access to housing, education, health services and other items which tend to lead to improved health, lower rates of mortality and higher life expectancy. It is not surprising therefore that aggregate income has been a pretty good predictor of life expectancy historically. However correlation does not necessarily imply causality running from income to health. It could actually be that better health, as proxied by life expectancy, contributes to higher incomes, rather than vice versa. Better health can increase incomes because healthier individuals tend to be more productive than sick ones; on average they work harder, longer and are more capable of focusing efficiently on production tasks. Furthermore, better health may affect not just the level of income but also its growth rate through its effect on education. Healthier children spend more time at school and learn faster, thus acquiring more human capital which translates into higher growth rates of incomes later in life.

_

Preston curve:

The x-axis shows GDP per capita in 2005 international dollars, the y-axis shows life expectancy at birth. Each dot represents a particular country. The Preston curve indicates that individuals born in richer countries, on average, can expect to live longer than those born in poor countries. However, the link between income and life expectancy flattens out. This means that at low levels of per capita income, further increases in income are associated with large gains in life expectancy, but at high levels of income, increased income has little associated change in life expectancy. In other words, if the relationship is interpreted as being causal, then there are diminishing returns to income in terms of life expectancy.

______

Literacy:

Literacy is the ability to read and write with understanding in any language. This is a definition which closely matches the UNESCO’s definition.

_

_

Why Education Matters:

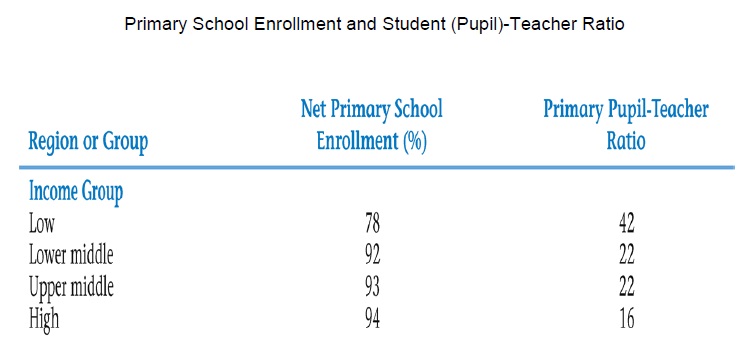

Education is the single best investment in prosperous, healthy and equitable societies. No country has ever achieved rapid and continuous economic growth without at least a 40% literacy rate. In sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in 4 children does not attend school; of those who attend, 1 in 3 will drop out before completing primary school. Worldwide, 69 million children are not in school; of those, 60% are girls. A single year of primary school increases a boy’s future earning potential by five to 15% and a girl’s even more. A child born to a literate mother is 50% more likely to survive past the age of five. Education provides a direct path towards food security and out of poverty. Education and food security are directly connected: doubling primary school attendance among impoverished rural children can cut food insecurity by up to 25. Educated parents are able to earn an income, produce more food through agricultural initiatives, and feed their children. Children who complete primary education are more likely to achieve food security as adults and end the cycle of poverty in their generation. Education leads to improved social, cognitive and health outcomes. Education increases people’s confidence, enabling them to become self-sufficient, fully contributing members of their communities. Education leads to gender equality and equity – girls and women who achieve higher levels of education are greater contributors to overall economic development and to children’s welfare within communities. Achieving educational equity for girls – including educating communities on the value of girls’ education – is an essential factor in sustainable poverty alleviation. Education is the single-most important driver of economic empowerment for individuals and countries.

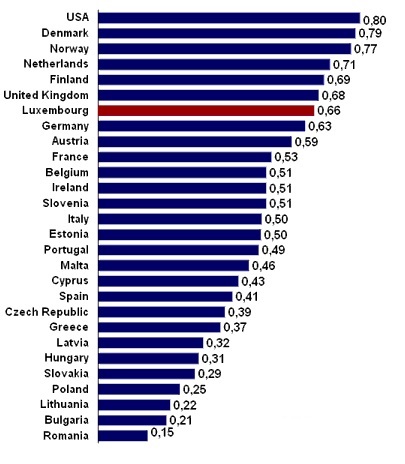

_

Literacy and economic growth:

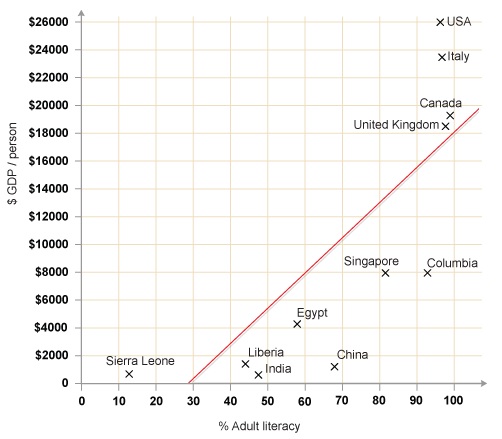

Literacy is always considered to be an important key for socio-economic growth. Economic prosperity of a country entirely depends on the economic resources it has and human resource is an important part of economic resource. Human resource includes the population, its growth rate, skills, standard of living and the working capacity of the labor force and all the above factors can be enhanced by increasing the literacy rate of a population. Thus literacy rate plays a key role in economic growth of a country. Japan can be an example where an economy has developed by excelling in human resources despite the deficiency of natural resource. As the biggest asset India has is its human resource, effective utilization of the human resource becomes very crucial for the country’s economic progress and thus literacy plays all the more an important role in determining India’s growth. Just being literate does not make people competent enough to enter the labor force in the market. Moreover enhancing additional supplementary skills is a necessity in an economy which has a lot of structural unemployment. It will reduce the occupational immobility of labor and will also improve the employability of the labor supply. Unskilled labors are seasonally employed, mainly in agricultural fields, and paid minimal wages. Imbibing skills in these workers will ensure them more permanent jobs and higher wage rates. Agricultural sector, which employs more than 50% of the workforce in India, is highly unproductive. Imbibing technical skills in these workers will enable them to work in productive, decent-wage jobs in industries. Thus enabling better utilization of human capital and making most of the human resource. Because we have lacked direct measures for ‘skills,’ indicators of educational attainment have typically been used as a proxy measure, with educational attainment being measured either as years of schooling or as highest level of education completed, ranging from less than high school to having one or more university degrees. Friedrich Huebler (2005) shows the correlation between GDP per capita and education by plotting the school net enrolment ratios (NER) against GDP per capita of 120 different countries. Higher the income levels of a country, higher the levels of school enrolment. However, these indirect indicators cannot distinguish between the acquisition of specific knowledge versus general literacy skills. The development of new surveys that allow ‘skill’ to be measured more directly have permitted researchers to tackle these issues. One such survey is the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) which provides measures of directly-assessed literacy skills for the population aged 16 to 65 years for twenty-three OECD countries. A recent study used data from IALS to investigate the relationship between educational attainment, literacy skills and economic growth. That study found that investment in human capital, that is, in education and skills training, is three times as important to economic growth over the long run as investment in physical capital, such as machinery and equipment. The results also show that direct measures of human capital based on literacy scores perform better than years-of-schooling indicators when explaining growth in output per capita and per worker. One of the study’s key conclusions is that human capital accumulation matters a great deal for the long-run wellbeing of nations. In fact, the study suggests that differences in average skill levels among OECD countries explain fully 55% of the differences in economic growth over the 1960 to 1994 period. This implies that investments in raising the average level of skills could yield large economic returns. Furthermore, the study finds that the average literacy score in a given population is a better indicator of growth than one based solely on the percentage of the population with very high literacy scores. In other words, a country that focuses on promoting strong literacy skills widely throughout its population will be more successful in fostering growth and wellbeing than one in which the gap between high-skill and low-skill groups is large. Also using data from IALS, Green and Riddell focused their research on individuals, rather than countries, to determine the relative contributions of education and literacy skills to earnings levels. Green and Riddell found that each additional year of education raises earnings by approximately 8%.

_

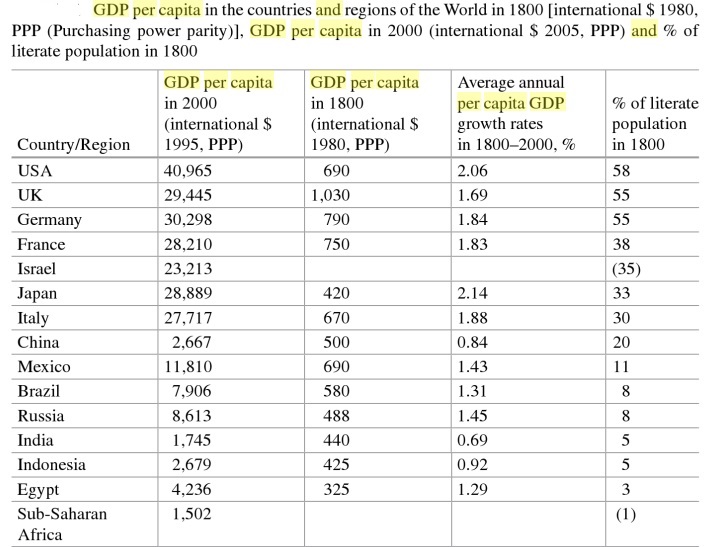

The Relationship between Literacy Rate and GDP per Capita:

There is sufficient evidence to conclude that there is a positive relationship between literacy rate and the log of GDP per capita for all world countries. The graph above shows a clear positive correlation between adult literacy and GDP per capita. Developed countries such as the USA and the United Kingdom have high literacy rates as well; poorer countries such as Sierra Leone and Liberia have lower literacy rates as well. From another observational study, authors conclude that there is a positive, exponential relationship between literacy rate and GDP per capita of world countries. This means that as literacy rate increases, so does GDP per capita.

_

Western developed nations had high literacy rate even in the year 1800 and even that time GDP per capita was higher in them compared to developing nations.

_

Literacy and population growth:

When a study of India’s population growth is done over the past century, it depicts a typical case of classical theory of demographic transition. According to the classical demographic transition model, a country undergoes a transition from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates as it develops from a pre-industrial to an industrialized economic system. The population of India in 1901 was 238 million with a density of 77 per sq km, from 1901-1921 India almost had a stagnant population. The period 1921-1951 saw India having a steady growth rate but from 1951-1981 the country underwent a rapid high growth in population with growth rate averaging around 19%. From 1981-2001 India faced high growth with definite slowing down. The latest census data of 2011 also shows this slowing down as India’s population grew at a rate of 17.64% in the past decade. India has successively passed through all the phases of demographic transition and is now widely believed to have entered the fifth phase, characterized by rapidly declining fertility. When the total fertility rate (TFR) data of past 50 years is considered, it has come down from 5.9 in 1960 to 2.65 in 2010. If literacy rate in the same period is considered, India had a literacy rate of mere 6% in 1901. It has been on an increase ever since. After independence schooling was made free and compulsory for children aged between 6 and 14 under the Right to Education Act. If data of past 50 years is considered, literacy rate has increased from 28.31% in 1961 to 74.04% in 2011. So if one notices there has been an increase in the literacy rate and a decrease in TFR. Studies show a very strong negative correlation between literacy rate and TFR and thus a strong reduction in population growth rate with an increase in literacy.

_

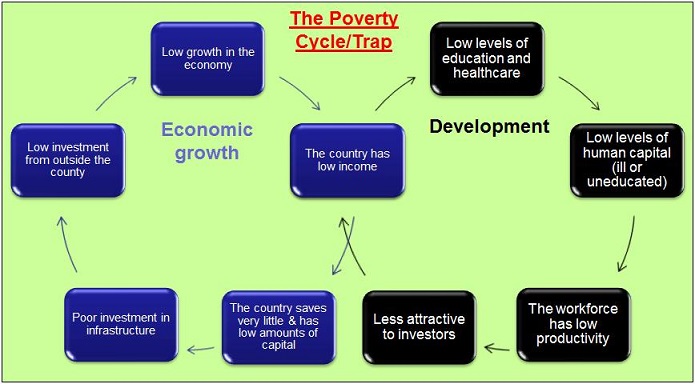

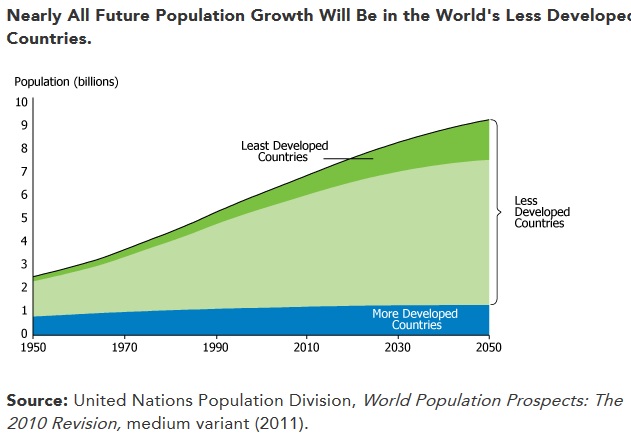

Education to reduce fertility rate:

Fertility rates tend to be highest in the world’s least developed countries. When mortality rates decline quickly but fertility rates fail to follow, countries can find it harder to reduce poverty. Poverty, in turn, increases the likelihood of having many children, trapping families and countries in a vicious cycle. Conversely, countries that quickly slow population growth can receive a “demographic bonus”: the economic and social rewards that come from a smaller number of young dependents relative to the number of working adults. For longer term population stability the goal is to reach replacement-level fertility, which is close to 2 children per woman in places where mortality rates are low. Industrial countries as a group have moved below this level. Some developing countries have made progress in reducing fertility, but fertility rates in the least developed countries as a group remain above 4 children per woman. One of the most effective ways to lower population growth and reduce poverty is to provide adequate education for both girls and boys. Countries in which more children are enrolled in school—even at the primary level—tend to have strikingly lower fertility rates.

_

Primary School Enrolment and Total Fertility Rates for Selected Countries:

| Rank | Country | Primary School Enrolment | Total Fertility Rate |

| Percent | Number of children per woman |

||

| 1 | Japan | 100.0 | 1.3 |

| 2 | Spain | 99.8 | 1.5 |

| 3 | Iran | 99.7 | 1.8 |

| 4 | Georgia | 99.6 | 1.6 |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 99.6 | 1.9 |

| … | |||

| 181 | Equatorial Guinea | 53.5 | 5.3 |

| 182 | Guinea-Bissau | 52.1 | 5.7 |

| 183 | Djibouti | 40.1 | 3.9 |

| 184 | Sudan | 39.2 | 4.2 |

| 185 | Eritrea | 35.7 | 4.6 |

_

Female education is especially important. Research consistently shows that women who are empowered through education tend to have fewer children and have them later. If and when they do become mothers, they tend to be healthier and raise healthier children, who then also stay in school longer. They earn more money with which to support their families, and contribute more to their communities’ economic growth. Indeed, educating girls can transform whole communities. School meal programs help improve all children’s attendance in low-income countries, but for girls the benefit is profound. Girls are more likely to be expected to contribute to their families by working at home, so sending each additional girl to school may cost her family not only tuition but labor as well. Providing free meals at school helps to offset these costs, particularly when programs include take-home rations. As a result, girls are both more likely to go to school and to keep coming back year after year. This is significant because girls who reach secondary school are especially likely to have fewer children. Worldwide, 69 million elementary-school-aged children were not in school in 2008, 37 million fewer than in 1999. By 2005, almost two thirds of developing countries had achieved gender parity in elementary school enrolment. Still, a majority of children not in school are female, and early marriage and motherhood keep many of the world’s poorest girls from completing secondary school. Extending educational opportunities to all the world’s children can clearly reap vast rewards in lower population growth—which in turn brings greater stability, prosperity, and environmental sustainability.

______

Fertility and economic growth:

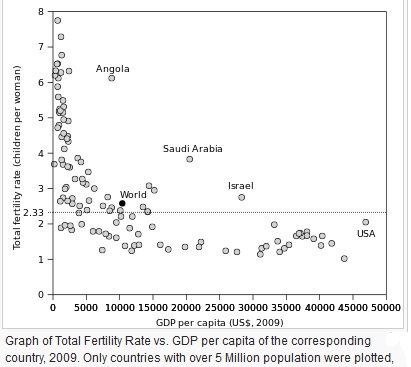

Contrary to the idea of population growth having an impact on economic growth, it can be more confidently put that economic growth does impact the population growth and slows it down. When the fertility rate in 171 countries was plotted against the GNI (Gross National Income) by Philip N. Cohen in 2009, the graph, shown below, was showing lower fertility rates with nations with higher GNI than the nations with lower GNI. This can be inferred to as declining fertility rates for an economy with increasing growth.

_

Demographic-economic paradox:

The demographic-economic “paradox” is the inverse correlation found between wealth and fertility within and between nations. The higher the degree of education and GDP per capita of a human population, subpopulation or social stratum, the fewer children are born in any industrialized country. In a 1974 UN population conference in Bucharest, Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India, illustrated this trend by stating “Development is the best contraceptive.” The term “paradox” comes from the notion that greater means would enable the production of more offspring as suggested by the influential Thomas Malthus. Roughly speaking, nations or subpopulations with higher GDP per capita are observed to have fewer children, even though a richer population can support more children. It is hypothesized that the observed trend has come about as a response to increased life expectancy, reduced childhood mortality, improved female literacy and independence, and urbanization that all result from increased GDP per capita, consistent with the demographic transition model. A reduction in fertility can lead to an aging population which leads to a variety of problems. Some scholars have recently questioned the assumption that economic development and fertility are correlated in a simple negative manner. A study published in Nature in 2009 has found that when using the Human Development Index instead of the GDP as measure for economic development, fertility follows a j-shaped curve: with rising economic development, fertility rates indeed do drop at first, but then begin to rise again as the level of social and economic development increases, while still remaining below the replacement rate.

______

Correlation between indices for development:

The figure above shows that education is the single most important factor promoting development of a nation and population explosion is the single most important factor hampering development of a nation.

_________

Standard of living:

How do you define “standard of living”?

The World Bank says:

Standard of living is the level of well-being (of an individual, group or the population of a country) as measured by the level of income (for example, GNP per capita) or by the quantity of various goods and services consumed (for example, the number of cars per 1,000 people or the number of television sets per capita).

_

Standard of living is the level of wealth, comfort, material goods and necessities available to a certain socioeconomic class in a certain geographic area. The standard of living includes factors such as income, quality and availability of employment, class disparity, poverty rate, quality and affordability of housing, hours of work required to purchase necessities, gross domestic product, inflation rate, number of vacation days per year, affordable (or free) access to quality healthcare, quality and availability of education, life expectancy, incidence of disease, cost of goods and services, infrastructure, national economic growth, economic and political stability, political and religious freedom, environmental quality, climate and safety. The standard of living is closely related to quality of life. The standard of living is often used to compare geographic areas, such as the standard of living in the United States versus Canada, or the standard of living in St. Louis versus New York. The standard of living can also be used to compare distinct points in time. For example, compared with a century ago, the standard of living in the United States has improved greatly. The same amount of work buys an increased quantity of goods, and items that were once luxuries, such as refrigerators and automobiles, are now widely available. As well, leisure time and life expectancy have increased, and annual hours worked have decreased.

_

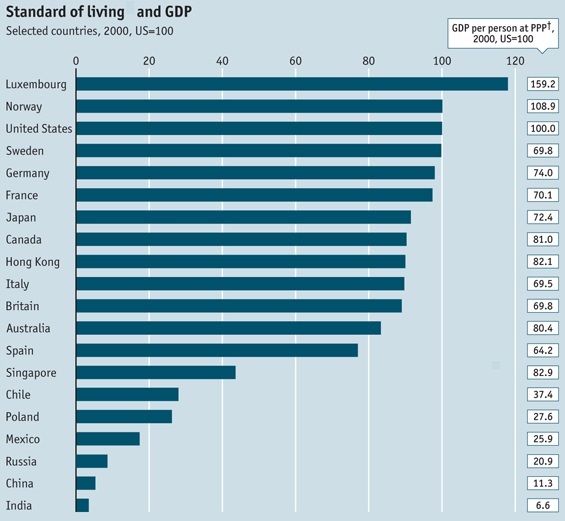

Standard of living in different nations:

_

Actual standard of living may be disguised:

As an example, countries with a very small, very rich upper class and a very large, very poor lower class may have a high mean level of income, even though the majority of people have a low “standard of living”. This mirrors the problem of poverty measurement, which also tends towards the relative. This illustrates how distribution of income can disguise the actual standard of living. Likewise Country A, a perfectly socialist country with very low average per capita income would receive a higher score for having lower income inequality than Country B with a higher income inequality, even if the bottom of Country B’s population distribution had a higher per capita income than Country A. Real examples of this include former East Germany compared to former West Germany or North Korea compared to South Korea. In each case, the socialist country has a low income discrepancy (and therefore would score high in that regard), but lower per capita incomes than a large majority of their neighbouring counterpart. This can be avoided by using the measure of income at various percentiles of the population rather than the highly relative and controversial income inequality.

_

Measurement of standard of living:

Standard of living is generally measured by standards such as real (i.e. inflation adjusted) income per person and poverty rate. Other measures such as access and quality of health care, income growth inequality, and educational standards are also used. Examples are access to certain goods (such as number of refrigerators per 1000 people), or measures of health such as life expectancy. It is the ease by which people living in a time or place are able to satisfy their needs and/or wants.

_

Ways to measure your standard of living include:

1. GDP per capita (discussed vide supra)

2. HDI (discussed vide supra)

3. Satisfaction with Life Index:

Developed by a psychologist at the University of Leicester, the Satisfaction with Life Index attempts to measure happiness directly, by asking people how happy they are with their health, wealth, and education, and assigning a weighting to these answers. This concept is related to the idea of Gross National Happiness that came from Bhutan in the 1970’s. The idea is that material and spiritual development should take place side by side, underpinned by sustainable development, cultural values, conservation, and good governance.

4. Happy Planet Index:

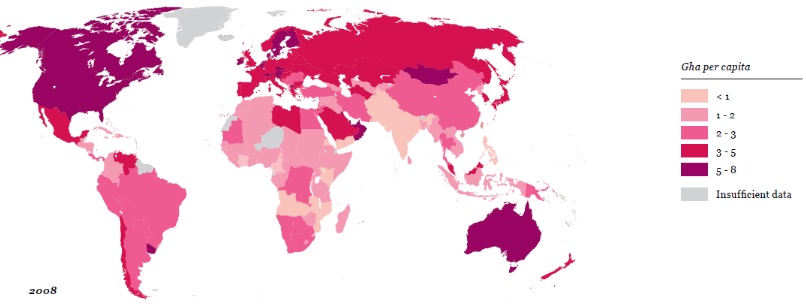

The Happy Planet Index was introduced by the New Economics Foundation in 2006. The premise is that what people really want is to live long and fulfilling lives, not just to be filthy rich. The kicker is that this has to be sustainable both worldwide and down through the generations. The HPI is calculated based on life satisfaction, life expectancy, and ecological footprint. It doesn’t measure how happy a country is, but how environmentally efficient it is to support well-being in that country. In other words, if people are happy but they’re guzzling more than their fair share of natural resources, the country will not have a high Happy Planet Index. But if people are happy and have a medium environmental impact, or are moderately happy and with a low impact, the country’s score will be high.

_

A new measure of standard of living:

Many people complain that conventional measures of GDP fail to capture a country’s true standard of living. But their attempts to improve on these conventional metrics are ad hoc. In a new paper Charles Jones and Peter Klenow of Stanford University propose a new measure of standards of living based on a simple thought experiment: if you were reborn as a random member of another country, how much could you expect to consume, in goods and leisure, over the course of your life? America, for example, has a higher GDP per person than France. But Americans also tend to work longer hours and live shorter lives. They also belong to a less equal society. If you assume that people do not know what position in society they will occupy, and that they dislike being poor more than they like being rich, they should prefer more egalitarian societies, everything else equal. For these reasons, the authors calculate that France and America have about the same standard of living as seen in the figure below. Nonetheless, broadly speaking, the figure below also shows falling standard of living with lower GDP per capita.

______

Comparing Standards of Living in the Global Economy:

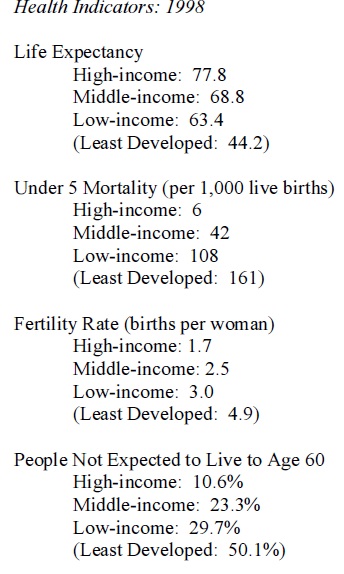

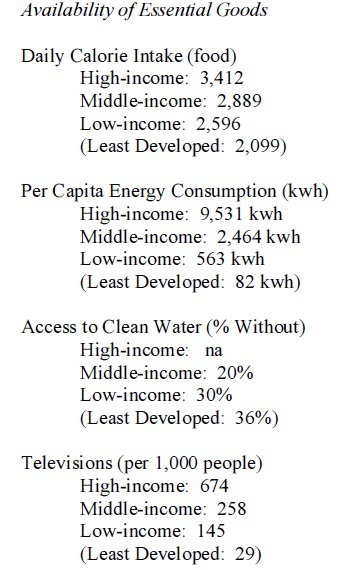

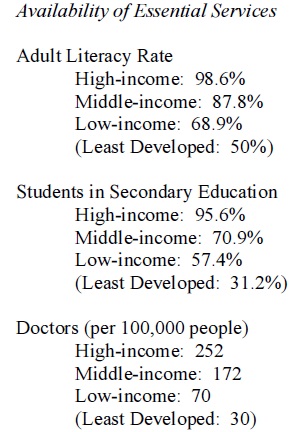

People living in the developed countries of the world enjoy a higher standard of living than people living in the developing or transition countries. It is not possible to measure with any precision standard of living for peoples living in different world regions, who have different histories and cultures, and different values and world views. Yet, by examining some basic indicators, as shown below, we can piece together a general profile of a country and make some general commentary on the overall standard of living for the 7 billion people inhabiting the planet today. The standard of living comparisons will be made according to income status: high income countries, middle-income countries, and low-income countries.

_

Health indicators:

_

Availability of essential goods:

_

Availability of essential services:

_

As noted in three tables above, high income countries have best health indicators and maximum availability of essential services and goods. In other words, their standard of living is higher than middle and low income countries. In other words, high income countries are developed nations and rest developing nations.

______

Quality of Life versus Standard of Living:

Quality of life and standard of living are often used interchangeably. But in fact they are two different concepts that are not necessarily related. Standard of living is generally measured by levels of consumption and thus, by levels of income. Satisfaction of basic needs of food, clothing and shelter are all standard of living issues. Quality of life is related to feeling good about one’s life and one’s self. One can have a very high standard of living and a low quality of life. And one can have a low standard of living and a high quality of life. It is not strange that we tend to confuse quality of life and standard of living.

• Increase in income may bring material comfort, but it certainly does not make one happy in life. This means that a high standard of living is no guaranty of a high quality of life.

• Standard of living is measurable as it is composed of indicators that are tangible and quantifiable. On the other hand, there are factors such as happiness, freedom and liberty in quality of life that are subjective and hard to evaluate.

_

An evaluation of standard of living commonly includes the following factors:

•income

•quality and availability of employment

•class disparity

•poverty rate

•quality and affordability of housing

•hours of work required to purchase necessities

•gross domestic product (GDP)

•inflation rate

•number of paid vacation days per year

•affordable access to quality health care

•quality and availability of education

•life expectancy

•incidence of disease

•cost of goods and services

•infrastructure

•national economic growth

•economic and political stability

•political and religious freedom

•environmental quality

•climate

•safety

When you think about standard of living, you can think about things that are easy to quantify. We can measure factors like life expectancy, inflation rate and the average number of paid vacation days workers receive each year, for example.

_

Factors that may be used to measure quality of life include the following:

•freedom from slavery and torture

•equal protection of the law

•freedom from discrimination

•freedom of movement

•freedom of residence within one’s home country

•presumption of innocence unless proved guilty

•right to marry

•right to have a family

•right to be treated equally without regard to gender, race, language, religion, political beliefs, nationality, socioeconomic status and more

•right to privacy

•freedom of thought

•freedom of religion

•free choice of employment

•right to fair pay

•equal pay for equal work

•right to vote

•right to rest and leisure

•right to education

•right to human dignity

_

The main difference between standard of living and quality of life is that the former is more objective, while the latter is more subjective. Standard of living factors such as gross domestic product, poverty rate and environmental quality, can all be measured and defined with numbers, while quality of life factors like equal protection of the law, freedom from discrimination and freedom of religion, are more difficult to measure and are particularly qualitative. Both indicators are flawed, but they can help us get a general picture of what life is like in a particular location at a particular time. While standard of living is more concerned with a predetermined, artificial status that has become accepted as a measure of good living, quality of life is focused on more intangible objects that do not necessarily depend on wealth.

_

Other approaches to assessing Development and Developing Countries:

Legatum Prosperity Index:

Some organizations have devised other approaches to evaluating the progress of developed and developing countries. The London-based Legatum Institute describes its Prosperity Index as “the world’s only global assessment of prosperity based on both income and well-being.” The Legatum Prosperity Index scores and ranks countries’ prosperity based on eight “foundations for national development,” including: economy, entrepreneurship and opportunity, governance, education, health, safety and security, personal freedom and social capital. The most recent version of the Prosperity Index covers 110 countries, whereas the HDI evaluates development indicators for 187 countries.

_

Social progress index:

There have been numerous efforts to go beyond GDP to improve the measurement of national performance. The Social Progress Index is distinct from other wellbeing indices in its measurement of social progress directly, independently of economic development, in a way that is both holistic and rigorous. Most wellbeing indices, such as the Human Development Index and the OECD Your Better Life Index, incorporate GDP or other economic measures directly. These are worthy efforts to measure wellbeing and have laid important groundwork in the field. However, because they conflate economic and social factors, they cannot explain or unpack the relationship between economic development and social progress. The Social Progress Index has also been designed as a broad measurement framework that goes beyond the basic needs of the poorest countries, so that it is relevant to countries at all levels of income. It is a framework that aims to capture not just present challenges and today’s priorities, but also the challenges that countries will face as their economic prosperity rises.

________

Inadequacy of mainstream economics:

Our main tool for understanding poor countries – mainstream economics – is woefully inadequate and all about the rich world. A sample of 76,000 economics journal articles published between 1985 and 2005 shows that more papers were published about the United States than on Europe, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa combined. Economists start from the assumption that humans are individualistic, utility-maximising and strictly rational in a narrow sense. Actually many people are communitarian, social, non-calculating, uncertain about the future and often act according to sentiment or whim. Mainstream economics allows no theory of power or politics and can’t see the world economy as a system. The economic statistics on poor countries are awful. The most basic metric of development, GDP, should not be treated as an objective number but rather as a number that is a product of a process in which a range of arbitrary and controversial assumptions are made. The discrepancy between different GDP estimates is up to a half in some cases. In the least developed countries, statistics offices are usually underfunded and don’t have the resources to collect data often or well enough.

________

________

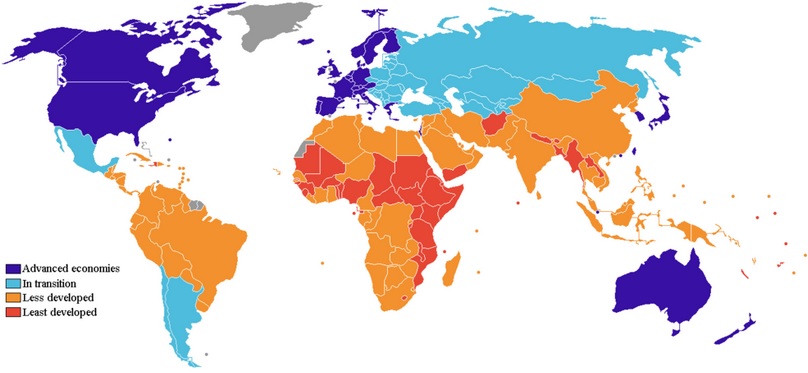

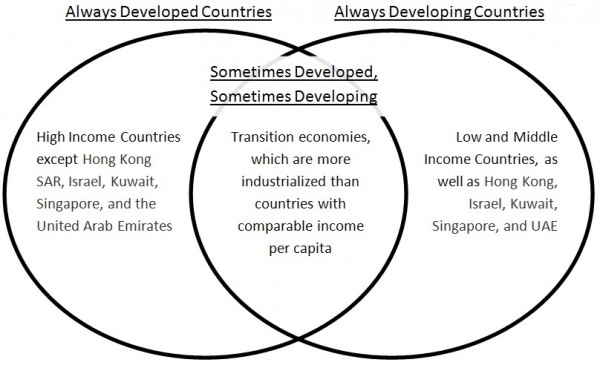

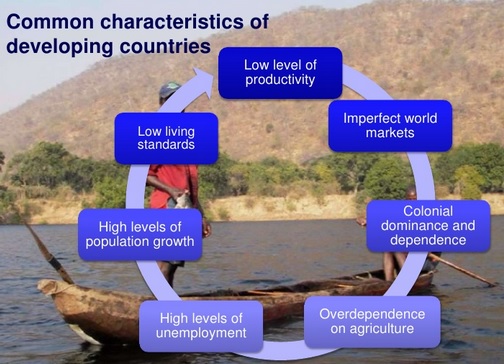

Classification of nations based on their development:

_

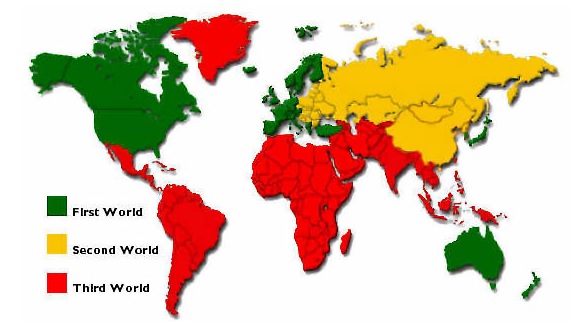

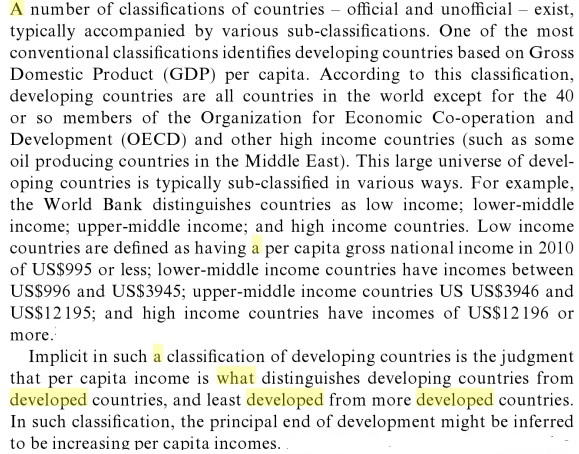

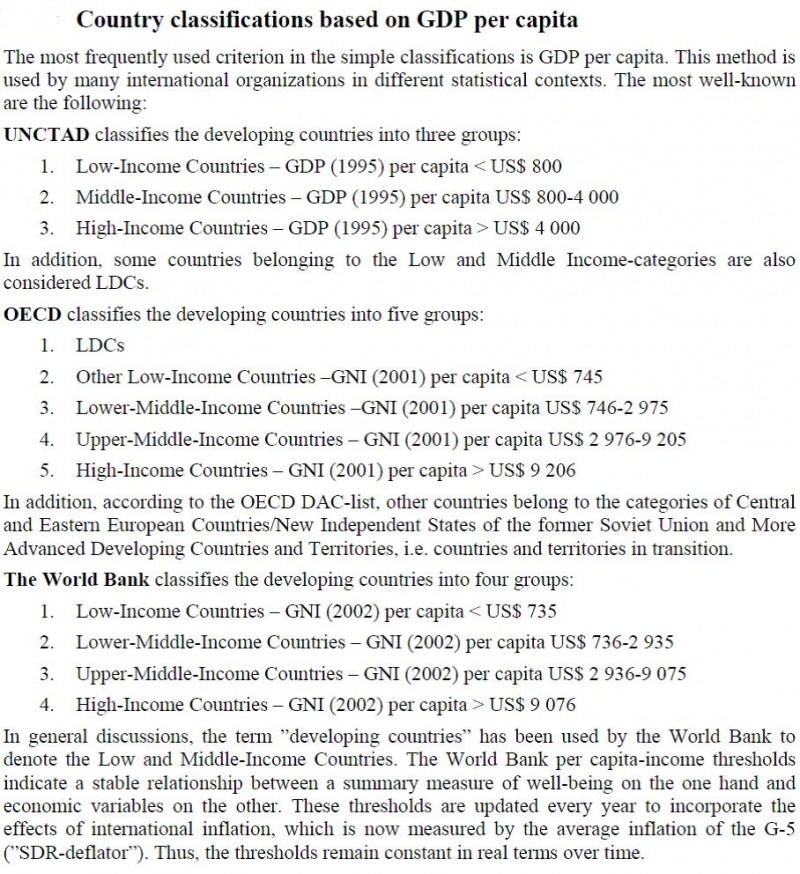

Four Worlds: