Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

YOGA

YOGA:

_

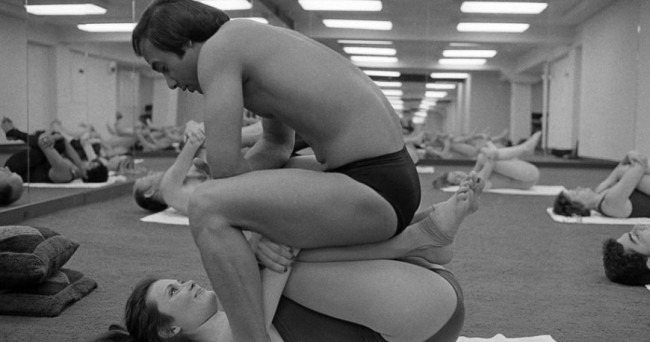

Marilyn Monroe performs dhanurasana (bow pose) in 1948:

Indra Devi opened yoga studio in Hollywood in 1948 and discovered ready students among movie stars, who found yoga’s breathing and relaxation techniques useful to their work. Her students included Greta Garbo, Gloria Swanson and Marilyn Monroe.

______

Prologue:

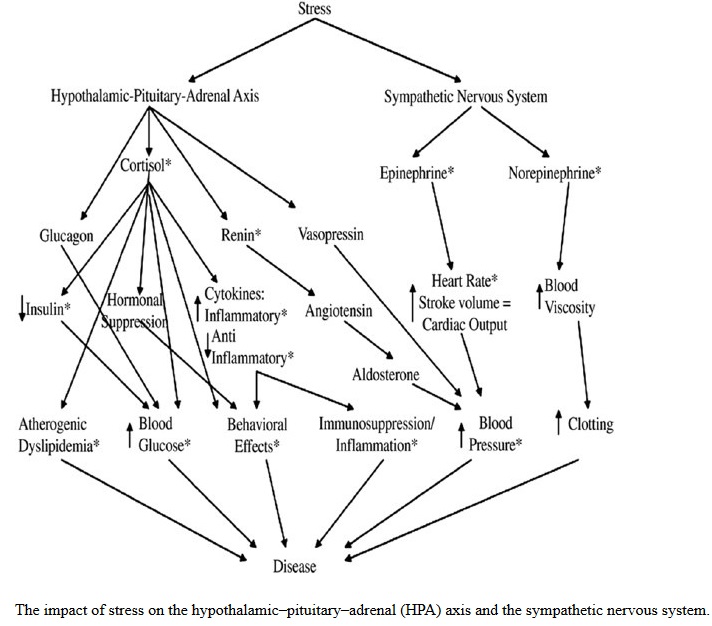

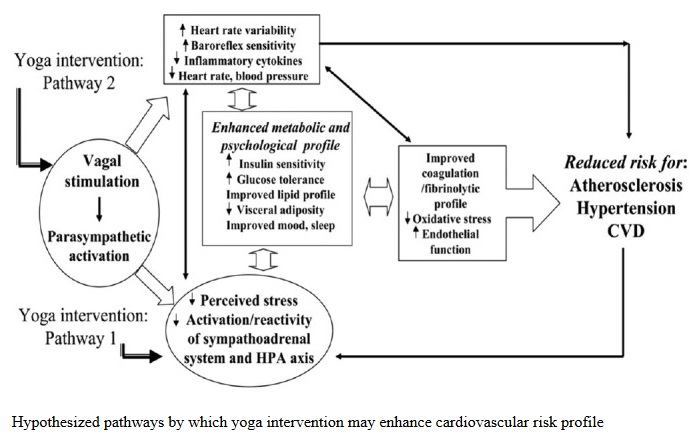

A considerable number of studies have identified prayer as a frequent and favoured coping method among patients providing each patient with comfort and strength. A variety of studies have attempted to test the efficacy of prayer and found no medical benefit. Prayers offered by strangers had no effect on the recovery of people who were undergoing heart surgery, a large and well-constructed study proved in 2006. The Cochrane Collaboration published a thorough review reaching the same conclusion in 2011 and counselled, “We are not convinced that further trials of this intervention should be undertaken and would prefer to see any resources available for such a trial used to investigate other questions in health care.” God’s medical career was over. But he left a void in the public discussion of medicine, and yoga has filled it. Studies come out on a near weekly basis trumpeting the benefits of yoga for any problem. Yoga for diabetes. Yoga for high blood pressure. Yoga for heart disease. Yoga for cancer. Yoga is a mind and body practice with historical origins in ancient Indian philosophy. Various styles of yoga combine physical postures, breathing techniques, meditation and relaxation. In thousands of years of yoga history, the term “yoga” has gone through a renaissance in current culture, exchanging the loincloth for a leotard and pair of leggings. Carl G. Jung the eminent Swiss psychologist, described yoga as ‘one of the greatest things the human mind has ever created.’ Yoga is considered science of the mind and fitness was not the chief aim of practice although yoga has become popular as a form of physical exercise based upon asanas (physical poses) to promote bodily or mental control and well-being. Sanskrit, the Indo-European language of the Vedas, India’s ancient religious texts, gave birth to both the literature and the technique of yoga. The Sanskrit word “yoga” has several translations and can be interpreted in many ways. Many translations point toward translations of “to yoke,” “join,” or “concentrate” – essentially as a means to unite body, mind and spirit. Yoga does not contradict or interfere with any religion, and may be practiced by everyone, whether they regard themselves as agnostics or members of a particular faith. Is yoga hype or science? I attempt to answer this question.

_________

Note:

The article is published with sole intention to study scientific basis of yoga. How to do yoga asana, pranayama and meditation with details of different asanas and different pranayamas, and details of specific asana/ pranayama for specific benefit is beyond scope of this article. Nobody should start doing yoga and nobody should stop doing yoga after reading this article. If you want to learn yoga, please contact competent & experienced yoga teacher. Please do read my article on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) published on this website in august 2010 as medical fraternity consider yoga as part of CAM.

________

Yoga terminology:

Yoga (Sanskrit: योग) is a Sanskrit word with a general meaning of “connection, conjunction, attachment, union”: a generic term for several physical, mental, and spiritual disciplines originating in ancient India. Hatha Yoga is the term Yoga is now colloquially (and more commonly) used to refer to as a school which emphasizes physical exercise within the tradition of Raja Yoga. Raja Yoga is a system of meditation in classical Vedanta philosophy. The word yoga, from the Sanskrit word yuj means to yoke or bind and is often interpreted as “union” or a method of discipline. A male who practices yoga is called a yogi, a female practitioner, a yogini.

_

A glossary of frequently used Yoga terms:

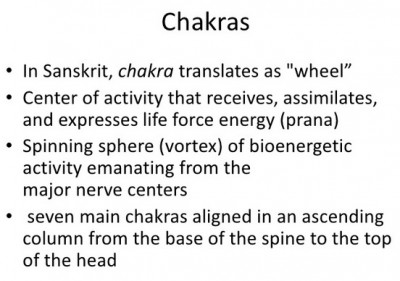

Asana: Asana is defined as “posture;” its literal meaning is “seat.” Originally, the asanas served as stable postures for prolonged meditation. More than just stretching, asanas open the energy channels (nadiis), and psychic centers (chakras) of the body. Asanas purify and strengthen the body and control and focus the mind. Asana is one of the eight limbs of classical Yoga, which states that asana should be steady and comfortable, firm yet relaxed. There are hundreds of different yoga postures, and they vary among the different styles and disciplines of Hatha Yoga. Teachers will often give the names of the postures in English, Sanskrit or a mix of the two.

_

Ashtanga: eight limbs of yoga practice. Each limb relates to an aspect of achieving a healthy and fulfilling life, and each builds upon the one before it.

_

Ayurveda: the ancient Indian science of health

_

Bhakti: devotion (as in Bhakti Yoga, the yoga of devotion)

_

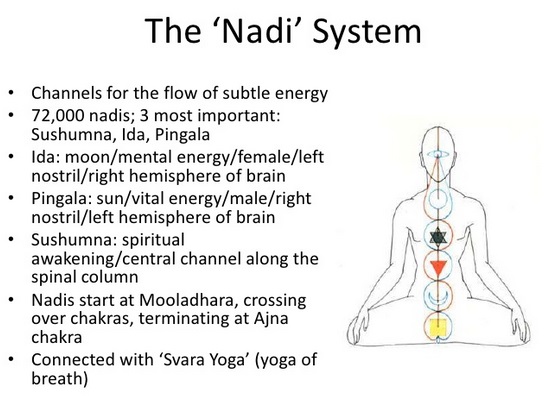

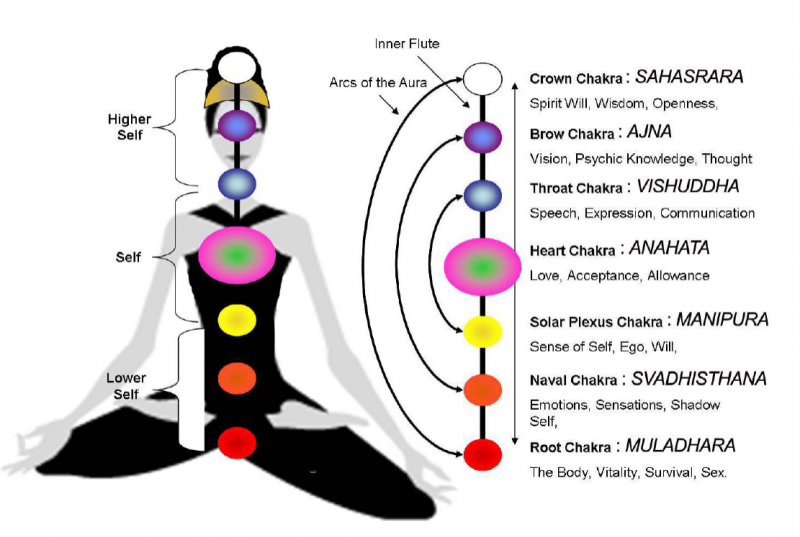

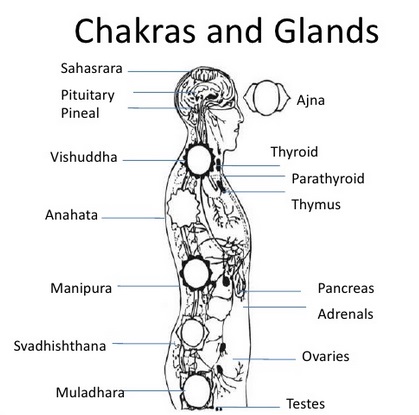

Chakra: Wheel of light – refers to each of the seven physical areas of the body wherein the three main nadis (Sushunma, Ida & Pingala) intersect. The basic system has seven chakras (root, sacrum, solar plexus, heart, throat, third eye and crown), each of which is associated with a color, element, syllable, significance, etc.

_

Drishti: gazing point used during asana practice

_

Mantra: a repeated sound, syllable, word or phrase; often used in chanting and meditation.

_

Meditation: Focusing and calming the mind often through breath work to reach deeper levels of consciousness.

_

Mudra: a hand gesture; the most common mudras are anjali mudra (pressing palms together at the heart) and gyana mudra (with the index finger and thumb touching)

_

Nadi: Channel for the movement of prana running through the body like a super highway. There are said to be 72,000 channels running through each body.

_

Namaste: “I bow to you”; a word used at the beginning and/or end of class which is most commonly translated as “the light within me bows to the light within you”; a common greeting in Indian cultures; a salutation said with the hands in anjali mudra.

_

Niyama: five living principles that (along with the yamas) make up the ethical and moral foundation of yoga; they include Sauca (purity), Santosha (contentment), Tapas (burning enthusiasm), Svadhyaya (self-study) and Ishvarapranidhana (celebration of the spiritual)

_

Om: the original syllable; chanted “A-U-M” at the beginning and/or end of many yoga classes

_

Prana: life energy; chi; qi

_

Pranayama: Breathing techniques to build prana, or energy, are known as pranayama. This is an important aspect of the yoga tradition and a part of the physical practice. When holding a yoga posture, make sure you can breathe slowly and deeply, using your breath control. A commonly used pranayama in Western classes is known as ujaii breathing, which mimics the sound of the ocean by constricting the throat. This technique links the breath with movements.

_

Samadhi: the state of complete Self-actualization; enlightenment

_

Savasana: corpse pose; final relaxation; typically performed at the end of every hatha yoga class, no matter what style

_

Surya Namaskar: Sun Salutations; a system of yoga exercises performed in a flow or series

_

Sutras: classical texts; the most famous in yoga is, of course, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

_

Ujjayi (a.k.a as Hissing Breath, Victorious Breath): A type of pranayama in which the lungs are fully expanded and the chest is puffed out; most often used in association with yoga poses, especially in the vinyasa style.

_

Vinyasa: Yoga posture sequences are a series of postures arranged to flow together one after the next. This is often called vinyasa or a yoga flow.

_______

World yoga day:

June 21 was declared as the International Day of Yoga by the United Nations General Assembly on December 11, 2014. The declaration of this day came after the call for the adoption of 21 June as International Day of Yoga by Indian PM Narendra Modi during his address to UN General Assembly on September 27, 2014. In December 2011, international humanitarian, meditation and yoga Guru Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and other yoga gurus supported the cause from the delegation of the Yoga Portuguese Confederation and together gave a call to the UN to declare June 21 as World Yoga Day. Following the adoption of the UN Resolution, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar lauded the efforts of PM Narendra Modi, stating that “It is very difficult for any philosophy, religion or culture to survive without state patronage. Yoga has existed so far almost like an orphan. Now, official recognition by the UN would further spread the benefit of yoga to the entire world.” “What is performed on the first International Yoga Day are the most popular, easy-to-do loosening exercises,” Isha, a Yoga instructor who learnt the art at Morarji Desai National Institute of Yoga (MDNIY) says, adding that there were over 8.4 million of these exercises. “Only the basic exercises are done on the International Yoga Day. These would certainly help people understand the importance of yoga in life.”

_

The figure below shows use of yoga over time:

_

Global yoga statistics:

There are 250 million estimated practitioners of yoga globally.

Around 20.4 million Americans practise yoga.

In the past few years, the number of people practicing yoga has grown about 30%. Interestingly, the amount of money that people are spending on this activity has grown by about 100%!

_

Yoga in America:

The 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) found yoga to be a growing complementary healthcare practice being utilized by approximately 6.1% of U.S. adults. Deep breathing exercises, known in yoga as “pranayama,” and meditation, another aspect often incorporated into yoga practice, were also popular complementary health practices among adults with 12.7% and 9.4%, respectively, of the population practicing (Barnes et al., 2008). The 2007 survey also found that more than 1.5 million children practiced yoga in the previous year. Many people who practice yoga do so to maintain their health and well-being, improve physical fitness, relieve stress, and enhance quality of life. In addition, they may be addressing specific health conditions, such as back pain, neck pain, arthritis, and anxiety. Across America, students, stressed-out young professionals, CEOs and retirees are among those who have embraced yoga, fuelling a $27 billion industry with more than 20 million practitioners — 83 percent of them women. More than 30 percent of Yoga Journal’s readership has a household income of over $100,000.

__

Top five reasons people report for taking up yoga are:

1. To increase flexibility;

2. General conditioning of their body and muscles;

3. To find stress relief;

4. To improve their overall health, and;

5. To become more physical fit.

_

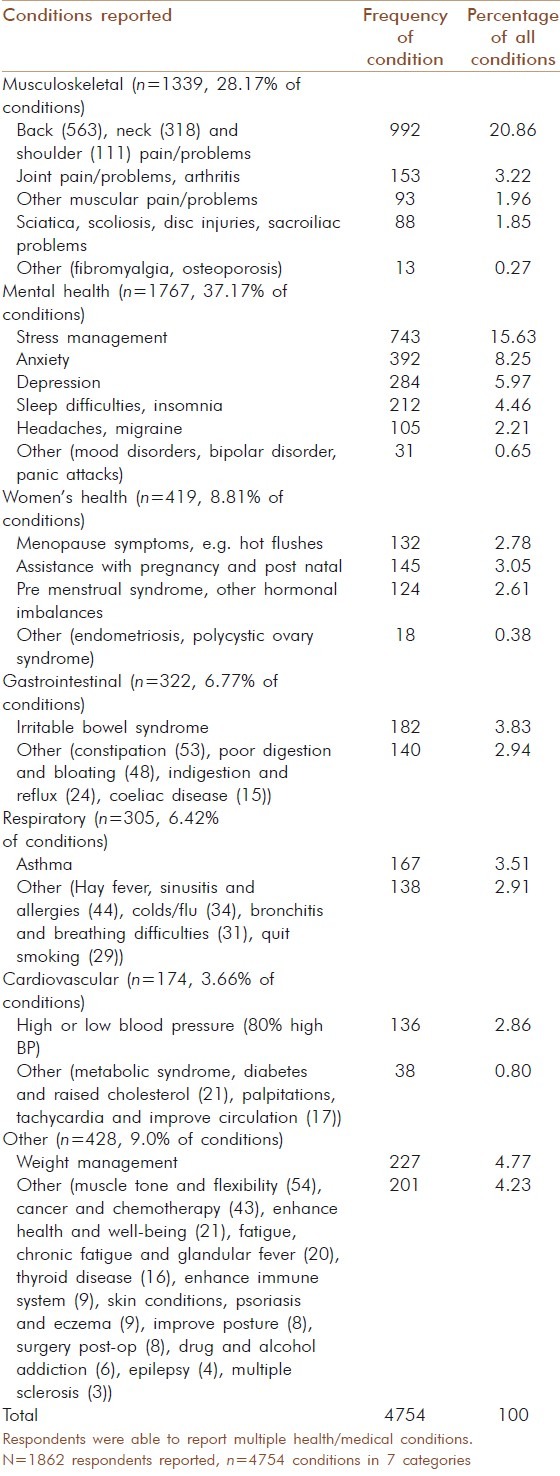

Yoga in Australia: Results of a national survey in 2012:

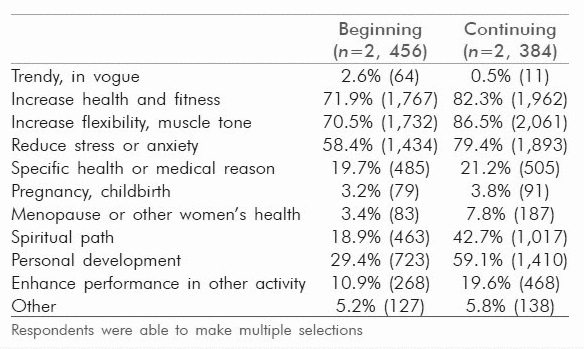

Motivations for beginning and continuing yoga practice:

_

_

Table above shows the reasons given for beginning and continuing yoga practice. Respondents were able to select multiple reasons. ‘Health and fitness’, and ‘increased flexibility/muscle tone’ were the most common reasons for starting (both about 71%) and continuing yoga practice (82% and 86% respectively). While 58.4% of respondents gave ‘reduce stress or anxiety’ as a reason for starting, 79.4% found this to be a reason for continuing. Only 19% of students initially saw yoga as a spiritual practice; however, this increased to 43% once practicing. Similarly, 29% initially saw yoga as a form of personal development, increasing to 59% as a reason for continuing to practice. About 20% indicated a specific health or medical reason for practice.

_

Why Yoga has become so popular in America? Why India is still not there?

Do you know that there are 20 million yoga practitioners in North America? Yoga has already become a gigantic industry in America if you include yoga studios, yoga retreats, and products like mats, clothing, shoes, and games like Wii fits, conferences, books and videos! Besides, media’s fascination with the fact that celebrities like Madonna and Sting are yoga practitioners glamorizes the image of yoga and leads to more Americans joining this bandwagon. So what is it about it about this 5000-year-old practice, originated in India, to resonate with Americans? All of us know that it can’t be that Americans are running out of options in the market of “keeping fit” as there are just plethora of exercise equipment, gyms, books, videos and exercise programs out there. It is no secret that Americans always had fascination for anything mystique, eastern or oriental with a spiritual flavor. On top of that they have an insatiable need to try anything which can keep them fit. The martial art studios, teaching arts like kung-fu, taekwondo, karate and judo did address both aspects to some extent, but remained confined to teenagers or people who were relatively younger. Somehow, most people could not integrate martial arts as a part of their life style as strenuous routines were hard for people as they got older. Whereas, Yoga’s adoption by all age groups grew in leaps and bounds and you couldn’t surpass a busy street without seeing anyone carrying a yoga mat. There are various flavors of yoga which is common in America like Vinyasa, Iyenger, Kundalini, Kriya, Bikram, power, mild, hath and many others – each is designed to meet you where you are and based on your needs. Yoga practitioners in America actually believe that they can find a yoga pose for every ailment in your body! Finally, Yoga is turning out to be much more than various “stretching” routines and is making them understand difference between “health” and “fitness”. Perhaps the best way to understand yoga’s popularity in America is to go right to the people who practice it. If you ask them why the practice, some of the more common replies you might hear are flexibility, increased energy, improved focus, reduction of the symptoms associated with stress and an overall good feeling. It is claimed that yoga can have a rejuvenating effect on all systems of the body including the circulatory, glandular system, digestive, nervous, musculoskeletal, and reproductive and respiratory systems. Let’s talk about Indian now! What is the state of Yoga in India? According to Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, a world-renowned spiritual leader, “If an individual can be credited with reviving yoga in India, it is solely Swami Ramdev. Unperturbed by issues and controversies generated, he has done a phenomenal job in re-introducing Yoga at a national level”. But Indians still have a long way to go as far as adaption of yoga at grassroots level is concerned. The percentage of population practicing it daily is very low if you compare it with America. Yoga is free and practice of yoga doesn’t require any investment other than time. Indians should be leading rest of the world again as far as yoga is concerned because it has always been a part of India’s tradition.

_

Commercialization of Yoga:

Most of what is billed as yoga around the world is not the yoga described in the Yoga Sutras or any of the original texts. Rather it has morphed into a form of asana without faith, devotion, or understanding underlying it, and therefore, more akin to mere exercise. New types of “yoga” seem to appear and disappear, it seems almost daily, and they are a far cry from the yoga described in the Yoga Sutras, Bhagavad Gita, or Upanishads. In today’s mass commercialization, the term “yoga” is loosely applied to the latest fitness creation that bears little to no resemblance to yoga as citta-vritti-nirodhah. The result of this has been a decline of yoga as an inward, spiritual quest or journey into a multi-million dollar commercialized industry. This commercialization is problematic in general, but it is of particular to concern to Hindus who see yoga being delinked from its roots. And though yoga is a means of spiritual attainment for any and all seekers, irrespective of faith or no faith, its underlying principles are those of Hindu thought. Yoga has gotten so big and has had such great commercial success that there is now a business category known as the “Yoga Industry”. Googling the term “Yoga Industry” reveals about 59,300,000 results.

__________

__________

Introduction to yoga:

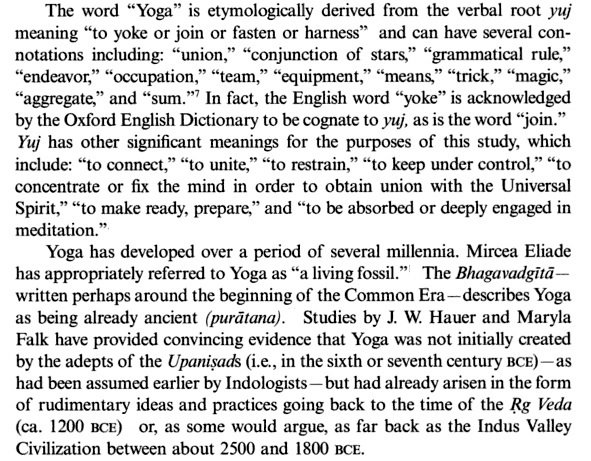

All of us know that Yoga originated in India and the history of yoga can be traced back to Indus Valley civilization. Maharshi Patanjali is regarded as the founder of yoga and “Yoga Sutras” written by him are considered by many as the foundational text of Yoga. The Sanskrit word yoga has many meanings and is derived from the Sanskrit root “yuj,” meaning “to control,” “to yoke” or “to unite. The word is basically associated with spiritual and meditative practices in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. Ironically, yoga was developed by men and practiced nearly exclusively by men for centuries. It is only in recent western history that so many women have flocked to the practice. Still, many present day popular teachers and gurus are men.

_

Yoga etymology:

_

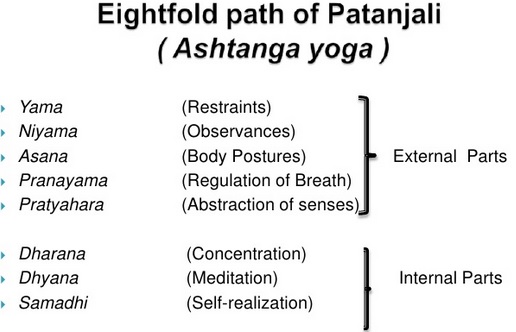

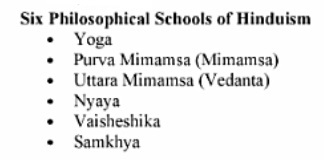

In philosophical terms, yoga refers to the union of the individual self with the universal self. Yoga is one of six branches of classical Indian philosophy and has been practiced for thousands of years. References to yoga are made throughout the Vedas, ancient Indian scriptures that are among the oldest texts in existence. Two thousand years ago the Indian sage Patanjali codified the various philosophies and methodologies of yoga into 196 aphorisms called “The Yoga Sutras,” which helped to define the modern practice of yoga. The Sutras outline eight limbs, or disciplines, of yoga: yamas (ethical disciplines), niyamas (individual observances), asana (postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (withdrawal of senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (self-realization, enlightenment). For common people, the term yoga usually refers to the third and fourth limbs, asana and pranayama, although traditionally the limbs are viewed as interrelated. Currently many styles of yoga are practiced (e.g., Iyengar, Ashtanga, Vini, Kundalini, Bikram), some of which are more closely tied to a traditional lineage than others. It is important to note that each of these approaches represents a distinct intervention, in the same way that psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, and interpersonal therapies each involve different approaches to psychotherapy. These styles of yoga emphasize different components and also have diverse approaches to and standards for teacher training and certification.

_

Yoga, in ancient times, was often referred to in terms of a tree with roots, trunk, branches, blossoms and fruits. Each branch of yoga has unique characteristics and represents a specific approach to life.

The six branches are:

1. Hatha yoga – physical and mental branch – involves asana and pranayama practice – preparing the body and mind

2. Raja yoga – meditation and strict adherence to the “eight limbs of yoga”

3. Karma yoga – path of service to consciously create a future free from negativity and selfishness caused by our actions

4. Bhakti yoga – path of devotion – a positive way to channel emotions and cultivate acceptance and tolerance

5. Jnana yoga – wisdom, the path of the scholar and intellect through study

6. Tantra yoga – pathway of ritual, ceremony or consummation of a relationship.

_

In other parts of the world where yoga is popular, notably the United States, yoga has become associated with the asanas (postures) of Hatha Yoga, which are popular as fitness exercises. Yoga as a means to enlightenment is central to Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Jainism, and has influenced other religious and spiritual practices throughout the world. The ultimate goal of yoga is the attainment of liberation (Moksha) from worldly suffering and the cycle of birth and death. Yoga entails mastery over the body, mind, and emotional self, and transcendence of desire. It is said to lead gradually to knowledge of the true nature of reality. The Yogi reaches an enlightened state where there is a cessation of thought and an experience of blissful union. This union may be of the individual soul (Atman) with the supreme Reality (Brahman), as in Vedanta philosophy; or with a specific god or goddess, as in theistic forms of Hinduism and some forms of Buddhism.

_

What does Om mean?

Om is a mantra, or vibration, that is traditionally chanted at the beginning and end of yoga sessions. It is said to be the sound of the universe. Chanting Om allows us to recognize our experience as a reflection of how the whole universe moves—the setting sun, the rising moon, the ebb and flow of the tides, the beating of our hearts. As we chant Om, it takes us for a ride on this universal movement, through our breath, our awareness, and our physical energy and we begin to sense a bigger connection that is both uplifting and soothing.

_

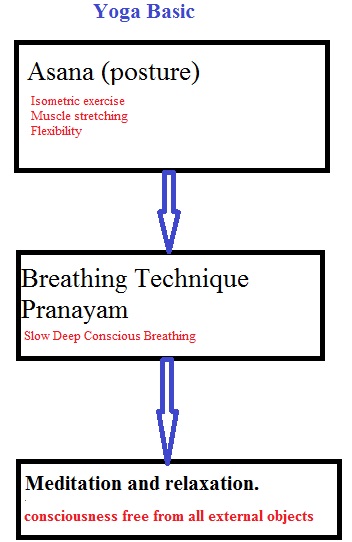

Yoga is a Hindu spiritual and ascetic discipline, a part of which, including breath control, simple meditation, and the adoption of specific bodily postures, is widely practised for health and relaxation. Yoga is an exercise practice that combines breathing exercises, physical postures, and meditation. The whole system of Yoga is built on three main structures: exercise, breathing, and meditation. The exercises of Yoga are designed to put pressure on the glandular systems of the body, thereby increasing its efficiency and total health. The body is looked upon as the primary instrument that enables us to work and evolve in the world, and so a Yoga student treats it with great care and respect. Breathing techniques are based on the concept that breath is the source of life in the body. The Yoga student gently increases breath control to improve the health and function of both body and mind. These two systems of exercise and breathing then prepare the body and mind for meditation, and the student finds an easy approach to a quiet mind that allows silence and healing from everyday stress. Regular daily practice of all three parts of this structure of Yoga produce a clear, bright mind and a strong, capable body.

_

Yoga is a full-body workout that increases flexibility, endurance, strength, balance and mental clarity through the use of postures, breathing techniques and concentration. It combines muscle strengthening and toning with flexibility and stretching exercises as well as breathing and meditation to attain maximum results. It is an exercise and meditation regimen that some people even consider to be a lifestyle. Yoga helps correct posture by increasing core strength and by encouraging correct alignment. To increase strength and endurance, participants practice holding static poses for longer periods of time. The mind and body exercise regimen requires the practitioner to focus on breathing. This helps reduce stress and anxiety and encourages relaxation and a sense of calm.

_

This is how I view yoga, a discipline involving controlled breathing, prescribed body positions, and meditation, with the goal of attaining a state of deep spiritual insight and tranquillity. First you have to adopt a specific posture to stretch muscles, improve flexibility and do isometric exercise. While doing posture, you concentrate on breathing. Controlled breathing helps to gain conscious control over bodily functions. Breath control and breathing exercise would lead to meditation and relaxation. Yoga is a synchronisation of posture, breathing and meditation.

_

Anyone can practise yoga. You don’t need special equipment or clothes – just a small amount of space and a strong desire for a healthier, more fulfilled life. The yoga postures or asanas exercise every part of the body, stretching and toning the muscles and joints, the spine and the entire skeletal system. And they work not only on the body’s frame but on the internal organs, glands and nerves as well, keeping all systems in radiant health. By releasing physical and mental tension, they also liberate vast resources of energy. The yogic breathing exercises known as pranayama revitalize the body and help to control the mind, leaving you feeling calm and refreshed, while the practice of positive thinking and meditation gives increased clarity, mental power and concentration. Yoga is a complete science of life that originated in India.

_

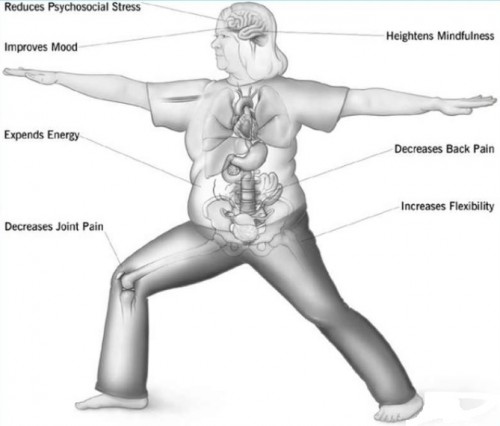

Yoga is traditionally believed to have beneficial effects on physical and emotional health. Over the last several decades, investigators have begun to subject these beliefs to empirical scrutiny. Most of the published studies on yoga were conducted in India, although a growing number of trials have been conducted in the United States and other Western countries. The effects of yoga have been explored in a number of patient populations, including individuals with asthma, cardiac conditions, arthritis, kyphosis, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, headache, depression, diabetes, pain disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, and addictions (among others),as well as in healthy individuals. In recent years, investigators have begun to examine the effects of yoga among cancer patients and survivors. The term cancer survivor here refers to individuals who have completed cancer treatment. The application of yoga as a therapeutic intervention, which began early in the twentieth century, takes advantage of the various psychophysiological benefits of the component practices. The physical exercises (asanas) may increase patient’s physical flexibility, coordination, and strength, while the breathing practices and meditation may calm and focus the mind to develop greater awareness and diminish anxiety, and thus result in higher quality of life. Other beneficial effects might involve a reduction of distress, blood pressure, and improvements in resilience, mood, and metabolic regulation.

_

According to the U.S. Department on Aging, there are four components to good physical health: strength, flexibility, balance and aerobic capacity. It is interesting to note that yoga can help you accomplish all these things, and no fancy piece of equipment is needed other than your own body and a yoga mat. Over the last 100 years, our lives have become very fast paced: cell phones, computers, internet, television. This, along with a strong work ethic, often results in people out of balance – people experiencing a lot of stress. Consequently, there is a strong need to de-stress, to quiet our minds and rejuvenate our bodies. And yoga helps achieve this, helping us return to a state of balance and health.

_

Definition of yoga:

There is no single definition of yoga. In order to experience truth through yoga, we must study its classical definitions and reflect on our own understanding of it. Yoga practices include posture (asana), breathing (pranayama), control of subtle forces (mudra and bandha), cleansing the body-mind (shat karma), visualizations, chanting of mantras, and many forms of meditation.

_

The Indian sage Patanjali is believed to have collated the practice of yoga into the Yoga Sutra an estimated 2,000 years ago. Patañjali’s work was composed in 400 CE plus or minus 25 years. The Sutra is a collection of 196 statements that serves as a philosophical guidebook for most of the yoga that is practiced today. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are widely regarded as the first compilation of the formal yoga philosophy. The verses of Yoga Sutras are terse. Many later Indian scholars studied them and published their commentaries, such as the Vyasa Bhashya (c. 350–450 CE). Patanjali’s yoga is also referred to as Raja yoga.

Patanjali defines the word “yoga” in his second sutra:

योग: चित्त-वृत्ति निरोध: (yogaḥ citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ) – Yoga Sutras 1.2

The great sage Patanjali, in the system of Raja Yoga, gave one of the best definitions of yoga. He said, ‘Yoga is the blocking (nirodha) of mental modifications (chitta vritti) so that the seer (drashta) re-identifies with the (higher) Self. Patanjali describes Yoga as ‘Chitta Viriddhi Nirodha’ or the opening up of the closed mind. The aim of Yoga is to reach one’s true self and to reach the goal, one has to let go of biases and prejudices. Patanjali’s system has come to be the epitome of Classical Yoga Philosophy and is one of the major philosophies of India. This terse definition hinges on the meaning of three Sanskrit terms. I. K. Taimni translates it as “Yoga is the inhibition (nirodhaḥ) of the modifications (vṛitti) of the mind (citta)”. Swami Vivekananda translates the sutra as “Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis).” Edwin Bryant explains that, to Patanjali, “Yoga essentially consists of meditative practices culminating in attaining a state of consciousness free from all modes of active or discursive thought, and of eventually attaining a state where consciousness is unaware of any object external to itself, that is, is only aware of its own nature as consciousness unmixed with any other object.”

_

_

According to Sage Patanjali, there are eight aspects of yoga, referred to as ashtanga yoga (Eight-Limbed Yoga), which includes yama (social discipline), niyama (personal discipline), asana (moulding the body into various positions), pranayama (regulation of the breath), pratyahara (involution of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and Samadhi (state of bliss). The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali discuss yoga practice in eight stages or limbs of yoga, which together provide a wholistic practice and the guiding principles to bring real happiness and lasting changes in our lives. Only one limb pertains to ‘asana’ (or postures). Classical yoga texts tell us that the last three of Patanjali’s limbs—dharana (deep concentration), dhyana (awareness of existence) and samadhi (oneness or enlightenment)—are to be practiced once we have a foundational understanding of yoga’s powers of illumination. According to B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga, we are ready to practice dharana once “the body has been tempered by asanas, when the mind has been refined by the fire of pranayama, and when the senses have been brought under control by pratyahara.”

_

Please do not confuse Patanjali’s ashtanga yoga with power yoga which is also called ashtanga yoga.

_

According to Jacobsen, Yoga has five principal meanings:

1. Yoga as a disciplined method for attaining a goal;

2. Yoga as techniques of controlling the body and the mind;

3. Yoga as a name of one of the schools or systems of philosophy (darśana);

4. Yoga in connection with other words, such as “hatha-, mantra-, and laya-,” referring to traditions specialising in particular techniques of yoga;

5. Yoga as the goal of Yoga practice.

_

Hatha Yoga:

The earliest references to hatha yoga are in Buddhist works dating from the eighth century. The earliest definition of hatha yoga is found in the 11th century Buddhist text Vimalaprabha, which defines it in relation to the center channel, bindu etc. The basic tenets of Hatha yoga were formulated by Shaiva ascetics Matsyendranath and Gorakshanath c. 900 CE. Hatha yoga synthesizes elements of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras with posture and breathing exercises. Hatha yoga, sometimes referred to as the “psychophysical yoga”, was further elaborated by Yogi Swatmarama, compiler of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika in 15th century CE. This yoga differs substantially from the Raja yoga of Patanjali in that it focuses on shatkarma, the purification of the physical body as leading to the purification of the mind (ha), and prana, or vital energy (tha). Compared to the seated asana, or sitting meditation posture, of Patanjali’s Raja yoga, it marks the development of asanas (plural) into the full body ‘postures’ now in popular usage and, along with its many modern variations, is the style that many people associate with the word yoga today. It is similar to a diving board – preparing the body for purification, so that it may be ready to receive higher techniques of meditation. The word “Hatha” comes from “Ha” which means Sun, and “Tha” which means Moon. This refers to the balance of masculine aspects—active, hot, sun—and feminine aspects—receptive, cool, moon—within all of us. Hatha yoga is a path toward creating balance and uniting opposites. In our physical bodies we develop a balance of strength and flexibility. We also learn to balance our effort and surrender in each pose. The word hatha also means willful or forceful. Hatha yoga includes postures (asana), breathing techniques (pranayama), purification techniques (shat karmas), and energy regulation techniques (mudra and bandha). The definition of yoga in the Hatha Yoga texts is the union of the upward force (prana) and the downward force (apana) at the navel center (manipura chakra). Hatha yoga teaches us to master the totality of our life force, which is also called prana. By learning how to feel and manipulate the life force, we access the source of our being. Hatha yoga is a powerful tool for self-transformation. It asks us to bring our attention to our breath, which helps us to still the fluctuations of the mind and be more present in the unfolding of each moment.

_

In the 1980s, yoga was connected to health, legitimizing yoga as a purely physical system of health exercises outside of counter-culture or esotericism circles, and unconnected to any religious denomination. Numerous asanas seemed modern in origin, and strongly overlapped with 19th and early-20th century Western exercise traditions. The West in the early 21st century typically associates the term “yoga” with Hatha yoga and its asanas (postures) or as a form of exercise. Since 2001, the popularity of yoga in the USA has risen constantly. The number of people who practiced some form of yoga has grown from 4 million (in 2001) to 20 million (in 2011). The American College of Sports Medicine supports the integration of yoga into the exercise regimens of healthy individuals as long as properly-trained professionals deliver instruction. The College cites yoga’s promotion of “profound mental, physical and spiritual awareness” and its benefits as a form of stretching, and as an enhancer of breath control and of core strength. Today most people practicing yoga are engaged in the third limb, asana, which is a program of physical postures designed to purify the body and provide the physical strength and stamina required for long periods of meditation.

________

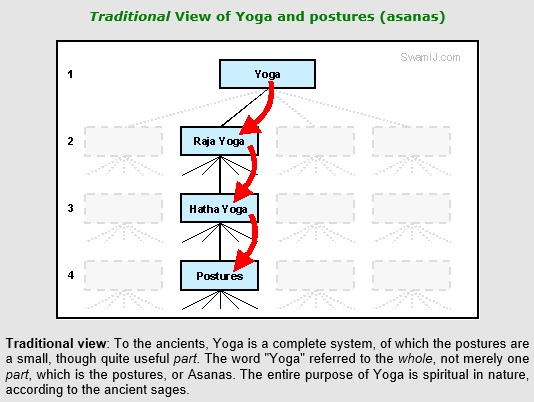

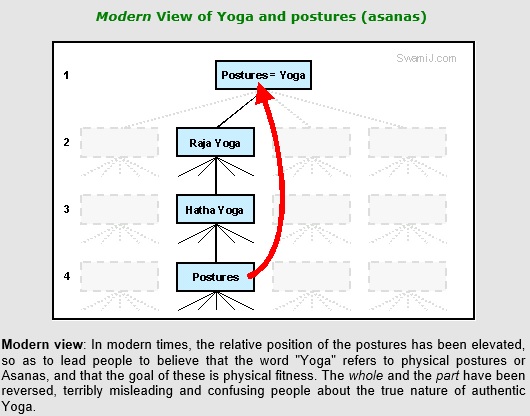

Modern Yoga versus Traditional Yoga:

The typical public perception of Yoga has shifted significantly in recent years. The starting point of most classes, books, magazines, articles, websites, and blogs on Yoga are so different from traditional Yoga of the ancient sages that it can be fairly called “Not Yoga”. The wave of Not Yoga seems to morph further and further away from Yoga. Yoga is now so totally altered that we can cry, get angry, or laugh, and laughing might be the most positive. Much, if not most of today’s Yoga can be called “gymnastic yoga” as it has emerged from the gymnastic practices of the late 1800s and early 1900s, not from the ancient traditions of Yoga. Other “styles” of modern Yoga are simply gross distortions. Traditional yoga has historically been taught orally, and there are subtle nuances among various lineages and teachers, rather than there being someone, precisely agreed upon “yoga”. Principles are usually communicated in sutra style, where brief outlines are expanded upon orally. For example, yoga is outlined in 196 sutras of the Yoga Sutras and then is discussed with and explained by teacher to student. Similarly, the great depth of meaning of Om mantra is expanded upon orally.

_

Traditional yoga:

_

_

Modern yoga:

The modern yoga widely practiced around the world today is derivative of Hatha Yoga, although it places a greater emphasis on asana (physical postures) than is found in traditional Hatha Yoga and includes innovations from Indian and foreign sources that are not to be found in traditional teachings on Hatha Yoga.

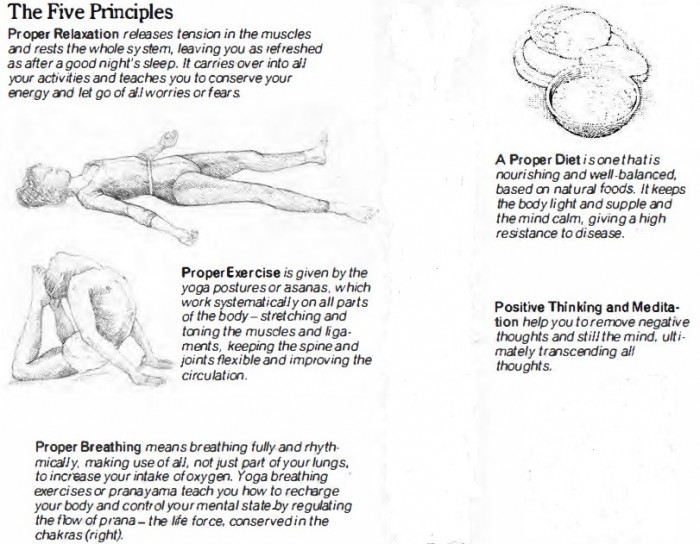

_

Modern yoga is based on five basic principles that were created by Swami Sivananda.

1. Savasana or proper relaxation;

2. Asanas or proper exercise;

3. Pranayama or proper breathing;

4. Proper diet; and

5. Dhyana or positive thinking and Meditation

_

_

In spite of the immense popularity of postural yoga worldwide, there is little or no evidence that asana (excepting certain seated postures of meditation) has ever been the primary aspect of any Indian yoga practice tradition… The primacy of asana performance in transnational yoga today is a new phenomenon that has no parallel in premodern times. The mere fact that one might do a few stretches with the physical body does not in itself mean that one is headed towards that high union referred to as Yoga. Many people work with diet, exercise and interpersonal relationships. This may include physical fitness classes, food or cooking seminars, or many forms of personality work, including support groups, psychotherapy, or confiding with friends. When done alone, these are not necessarily aimed towards Yoga, and are therefore not Yoga, however beneficial they may be. Yet, work with body, food, and relationships may very much fall under the domain of Yoga, when Yoga is the goal. The key is the goal or destination one holds in the heart, mind, and conviction. Without that being directed towards the state of Yoga, the methods can hardly be called Yoga. The goal of Yoga is Yoga, which has to do with the realization in direct experience of the highest unity of our being.

_

Perception has recently shifted: The typical perception of Yoga has shifted a great deal in the past century, particularly the past couple decades. Most of this is due to changes made in the West, particularly in the United States, though it is not solely an American phenomenon. The gist of the shift can be summarized in two perspectives, one of which is modern and false, and the other of which is ancient and true.

•False: Yoga is a physical system with a spiritual component.

•True: Yoga is a spiritual system with a physical component.

The false view spreads: Unfortunately, the view that Yoga is a physical exercise program is the dominant viewpoint. The false view then spreads through many institutions, classes, teachers, books, magazines, and millions of students of modern Yoga, who have little or no knowledge or interest in the spiritual goals of ancient, authentic, traditional Yoga and Yoga Meditation.

_

This is not yoga:

The misuse of the word Yoga often involves what logicians call the Fallacy of Composition. One version of the Fallacy of Composition is projecting a characteristic assumed by a part to be the characteristic assumed by the whole or by others. It may lead to false conclusion that whenever a person is doing some action that is included in Yoga, that person is necessarily doing Yoga. Here are some obviously unreasonable and false arguments about the nature of Yoga. These are given as examples of the absurdity of the fallacy of composition.

•Body flexing is part of Yoga; therefore, anybody who flexes the body is practicing Yoga.

•Breath regulation is part of Yoga; therefore, anybody who intentionally breathes smoothly and slowly is practicing Yoga.

•Cleansing the body is part of Yoga; therefore, anybody cleansing the body is practicing Yoga.

•Concentrating the mind is part of Yoga; therefore anybody who concentrates is practicing Yoga.

________

Asana, pranayama and meditation:

_

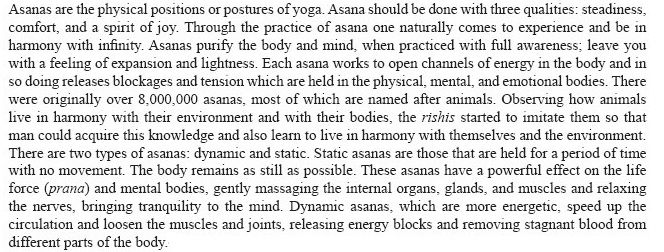

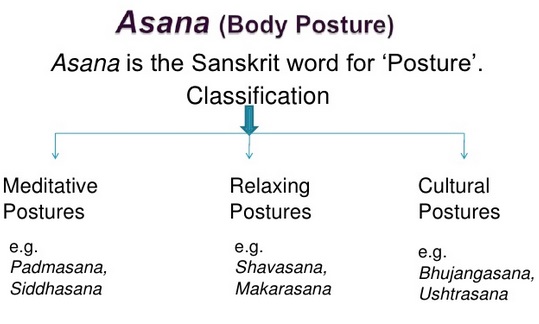

Asana:

_

Asanas are various body positions designed to improve health and remove diseases in the physical, causal, and subtle bodies. The word “asana” is Sanskrit for “seat”, which refers not only to the physical position of the body but also to the position of the body in relation to divinity. They were originally meant for Meditation, as the postures can make you feel relaxed for a long period of time. The regular practice of Asanas will grant the practitioner muscle flexibility and bone strength, as well as non-physical rewards such as the development of will power, concentration, and self-withdrawal. Asana is defined as “posture or pose;” its literal meaning is “seat.” Originally, there was only one asana– a stable and comfortable pose for prolonged seated meditation. Asana practice alone is shown to have a myriad of health benefits from lowering blood pressure, relief of back pain and arthritis, and boosting of the immune system. Increasingly, many believe asana practice to reduce Attention Deficit Disorder (AD/HD) in children, and recent studies have shown it improves general behavior and grades.

_

And while practicing asana for improved health is perfectly acceptable, it is not the goal or purpose of yoga. Perhaps the two most influential yoga gurus of our time, BKS Iygenar and Pattabhi Jois were clear about the intended purpose of asana. In interviews from 2004, re-published by Namarapa magazine in Fall 2014 issue, the two masters are quoted as follows:

“Asanas are not meant for physical fitness, but for conquering the elements, energy, and so on. So, how to balance the energy in the body, how to control the five elements, how to balance the various aspect of the mind without mixing them all together, and how to be able to perceive the difference between the gunas, and to experience that there is something behind them, operating in the world of man – that is what asanas are for. The process is slow and painstaking, but a steady inquiry facilitates a growing awareness.” – Iyengar

“But using it [yoga] for physical practice is no good, of no use – just a lot of sweating, pushing, and heavy breathing for nothing. The spiritual aspect, which is beyond the physical is the purpose of yoga. When the nervous system is purified, when your mind rests in the atman [the Self], then you can experience the true greatness of yoga. To practice asana and pranayama is to learn to control the body and the senses, so that the inner light can be experienced. That light is the same for the whole world.” – Jois

Still, both yoga masters recognized the importance of asana as vital and necessary to the practice of yoga. Asana is the limb through which most people enter the world of yoga, and its importance should not be diminished. Higher levels of yoga cannot be achieved if the physical body is weak, sick, or injured. Asana, when practiced under the guidance of a guru or an experienced and properly trained teacher, is integral to yoga. Unfortunately, the likes of Iygenar and Jois are difficult to come by, especially in much of today’s yoga culture which is driven by a Western-mentality of commercialization and commodification. Without such insight, wisdom, and proper guidance, modern day “yoga” is asana without understanding, faith, or intention, and therefore, merely remains at the level of physical exercise. In a 2005 interview published in Namarupa magazine, Prashant Iyengar, son of B.K.S. Iyengar, shared a similar view when he said, “We cannot expect that millions are practicing real yoga just because millions of people claim to be doing yoga all over the globe. What has spread all over the world is not yoga. It is not even non-yoga; it is un-yoga.”

_

_

Ideal time to start these asanas is in the morning. Morning times are quiet and conducive to perform asanas. The most important thing to bear in mind is to be aware or conscious of what one is doing during the asana practice. Inattention during the practice does not give favorable results. The aim is to observe, recognize and control the bodily movements. Yoga is one of the best means to understand the nature of the mind, body language and above all, self-study. Asanas are 80 percent mental and 20 percent physical. A regular routine should be adhered to, while following asana practice. While doing the asanas, one should be conscious of the stretch in the limbs and be aware of the flexibility of the joints. A general yoga routine should commence with padmasana, a sitting posture suitable for meditation. Apart from being conscious of bodily movements, one should start to observe breathing, heartbeat and the tension in the muscles. One must be able to distinguish the different states of tension, relaxation and other sensations in the body. The main emphasis of these asanas is, to assume a posture slowly, smoothly, and to be aware of the feelings that the posture helps to develop. The posture should be executed in a slow and controlled manner. Then focus should be on breathing. Controlled breathing helps to gain conscious control over bodily functions. Then one should relax into the posture. Relaxation is an important aspect in yoga practice. One should mentally tune oneself into yoga postures or visualize the posture one is going to practice. All the muscles must be in a relaxed position from the start to the final position, and practicing yoga makes one feel good. They should be executed in a slow, harmonious and continuous manner. To achieve a perfect posture should not be the aim, but rather one should have a non-striving attitude. Observation and concentration play a vital role. Introspection of one’s own thoughts and feelings too play a significant role. When thoughts invade the mind, they should be gently pushed away and attention should be gathered gently. Each yoga posture, which falls into phases, manifests itself in synchrony. One must listen to the body and should not stretch oneself beyond one’s capacity. Always do it in a relaxed and calm manner. The essence of yoga is to transform life into a healthy one. It changes and normalizes the incorrect pattern of living. Yoga re-energizes the mind and body.

_

_

The different postures or asanas include:

•lying postures

•sitting postures

•standing postures

•inverted or upside-down postures

_

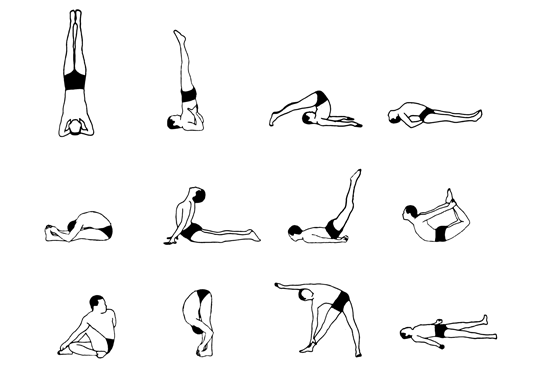

Asana is one of the eight limbs of classical Yoga, which states that poses should be steady and comfortable, firm yet relaxed helping a practitioner to become more aware of their body, mind, and environment. The 12 basic poses or asanas are much more than just stretching. They open the energy channels, chakras and psychic centers of the body while increasing flexibility of the spine, strengthening bones and stimulating the circulatory and immune systems. Along with proper breathing or pranayama, asanas also calm the mind and reduce stress.

_

12 basic asanas:

_

Yoga poses with animal names:

There are many yoga poses with animal names. It’s only natural, as the early yogis were influenced by what was around them. Animals have been instinctively practicing asana (yoga poses) for centuries. In fact, many of the yoga poses we have come to know in class were named after animals both for the resemblance itself, and for the quality of the animal itself. Ancient yogis observed animals in nature; their abilities and beauty. To emulate these animal qualities through asana was considered a high sign of spiritual enlightenment. Along with the dog, this asana menagerie includes other mammals (cow, camel, cat, horse, lion, monkey, bull), birds (eagle, peacock, goose or swan, crane, heron, rooster, pigeon, partridge), a fish and a frog, reptiles (cobra, crocodile, tortoise), and arthropods (locust, scorpion, firefly). There’s even a pose named after a mythic sea monster, the makara, the Hindu zodiac’s Capricorn, which is pictured as having the head and forelegs of a deer and the body and tail of a fish.

_

Padmasana:

_

Padmasana is a term derived from sanskrit word padma: lotus, and asana: seat or throne. While doing any asana, it is very important to be alert and be conscious of what we are doing. Concentration and relaxation play a vital role in the practice of yoga. Padmasana is also called kamalasana, which means lotus. The form of the legs while performing this asana gives the appearance of a lotus. It is the best asana for contemplation. As we start the asana, one must become conscious of the body. We must try to visualize the posture one is going to practice. This is actually a form of mental tuning. So we have to visualize before doing the asana. As one takes the right posture, one must close the eyes and be aware of the body. The Muscles must be relaxed. One should feel the touch of the legs on the floor. The focus should then be shifted to the breath. A feeling of peace touches the mind. Sit in this posture for a few Minutes before proceeding to the next asana.

Steps to follow for Padmasana:

1. Sit on the ground by spreading the legs forward.

2. Place the right foot on the left thigh and the left foot on the right thigh.

3. Place the hands on the knee joints.

4. Keep the body, back and head erect.

5. Eyes should be closed.

6. One can do Pranayama in this asana.

_

Mudra:

A mudra is a symbolic or ritual gesture in Hinduism and Buddhism. While some mudras involve the entire body, most are performed with the hands and fingers. In yoga, mudras are used in conjunction with pranayama (yogic breathing exercises), generally while seated in Padmasana, Sukhasana or Vajrasana pose, to stimulate different parts of the body involved with breathing and to affect the flow of prana in the body. The yoga teacher Satyananda Saraswati, founder of the Bihar School of Yoga, continued to emphasize the importance of mudras in his instructional text Asana, Pranayama, Mudra, Bandha.

_

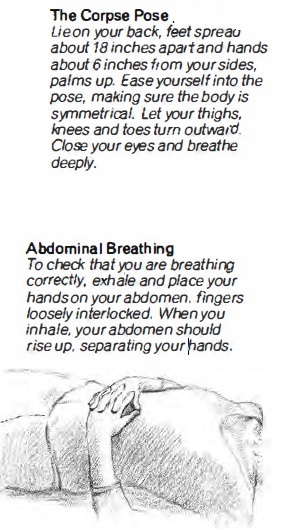

Savasana (The Corpse Pose):

_

The Corpse Pose or Savasana is the classic relaxation pose, practised before each session, between asanas, and in Final

Relaxation. It looks deceptively simple, but it is in fact one of the most difficult asanas to do well and one which changes and develops with practice. At the end of an asana session your Corpse Pose will be more complete than at the beginning because the other asanas will have progressively stretched and relaxed your muscles. When you first lie down, look to see that you are lying symmetrically as symmetry provides proper space for all parts to relax. Now start to work into the pose. Rotate your legs in and out then let them fall gently out to the sides. Do the same with your arms. Rotate the spine by turning your head from side to side to centre it. Then start stretching yourself out, as though someone were pulling your head away from your feet, your shoulders down and away from your neck, your legs down away from your pelvis. Let gravity embrace you. Feel your weight pulling you deeper into relaxation, melting your body into the floor. Breathe deeply and slowly from the abdomen (right), riding up and down on the breath, sinking deeper with each exhalation. Feel how your abdomen swells and falls. Many important physiological changes are taking place, reducing the body’s energy loss, removing stress, lowering your respiration and pulse rate, and resting the whole system. As you enter deep relaxation, you will feel your mind grow clear and detached.

_

_______

Yoga series (dynamic asana):

Yoga series consist of asanas done in sequence. The most common yoga series is Surya Namaskara or the Sun Salutation originating in the Hatha Yoga system. Ashtanga yoga (power yoga), Vinyasa Yoga and Bikram yoga are also considered as yoga series.

_

Ashtanga yoga:

Ashtanga is based on ancient yoga teachings, but it was popularized and brought to the West by Pattabhi Jois in the 1970s. It’s a rigorous style of yoga that follows a specific sequence of postures and is similar to vinyasa yoga, as each style links every movement to a breath. The difference is that ashtanga always performs the exact same poses in the exact same order. This is a hot, sweaty, physically demanding practice.

_

Vinyasa Yoga:

Vinyasa means flow in Sanskrit. In this practice of yoga vinyasas are completed between poses to refresh the body and prepare for the next posture. A vinyasa typically consists of chattaranga, followed by a cobra/ upward dog position into a downward dog. Downward dog is considered to be the restorative posture and is a resting pose to regain the ujjayi breath before moving on to the next posture.

_

Bikram Yoga:

Bikram Yoga is a style of yoga developed by Bikram Choudhury and a Los Angeles, California based company. Bikram Yoga is ideally practiced in a room heated to 105 °F (40.5 °C) with a humidity of 40%, and classes, which are 90 minutes long, are a guided series of 26 postures and two non-pranamic breathing exercises.

_

Surya Namaskara:

Sanskrit for Sun Salutation owes its name for expressing devotion (bhakti) to Surya, the solar deity in the Hindu pantheon, by concentrating on the Sun. The Sun Salutation is, for many yogis, an exercise to be performed at sun rise, or at least in the morning. Surya Namaskara is a sequence of twelve asanas, where the five beginning asanas are the same as the last five asanas of the sequence. The Sun Salutation can be practiced at varying levels of awareness, ranging from that of physical exercise, to a complete sadhana which incorporates asana, pranayama, mantra and chakra meditation.

_

______

Yoga and breathing:

Breathing is one of the most important parts of yoga. Breathing steadily while you’re in a yoga pose can help you get the most from the pose. But practicing breathing exercises when you’re not doing yoga poses can be good for you, too. It may seem strange to practice breathing, since we do it naturally every moment of our lives. But when people get stressed, their breathing often becomes shallower and more rapid. Paying attention to how you are breathing can help you notice how you’re feeling — it can give you a clue that you’re stressed even when you don’t realize it. So start by noticing how you’re breathing, then focus on slowing down and breathing more deeply.

_

The Importance of breath in Yoga:

Awareness of breath and synchronizing breath and movement is what makes yoga, yoga; and not gymnastics or any other physical practice. When focusing on the breath during our asana practice, the control of the breath shifts from the brain stem (medulla oblongata) to the cerebral cortex (evolved part of brain) due to us being aware of the breath. It’s in that moment, when we are aware, when the magic starts to happens. The mind will become quieter and a calm awareness arises. As a result emotional stress and random thoughts are less likely to occur. So basically the whole system gets a break. The energy, the prana, begins to flow more freely pushing through any emotional and physical blockages and thus freeing the body and mind which results in the “feel good” effect after a yoga practice. So we can safely say that breath has an intimate relationship to the overall movement of prana (life energy) throughout the entire body. Those who have practiced some serious meditation have apparently noticed and seen that when the breath moves, the mind moves as well. Of course this works both ways so as the mind moves, the breath moves too. This basically means that the breath gives us a tool with which we can explore the subtler structures of our mental and emotional worlds. When the breath changes, that tells you that something is happening in your mind. When something happens in your mind, like a disturbing thought for example, your breath will reflect that back to you. You will then understand that, because the breath and mind are so connected, awareness and mindfulness of breathing can lead to insight into the nature of mind. Insight into the nature of the mind leads eventually to freedom from suffering.

_

Accurate use of the breath adds an important dimension to the practice of asanas. It brings both physical and mental refinement and leads naturally and easily to the practice of yogic breathing or pranayama. For thousands of years, yogis have realized the profound relationship between one’s mental state and one’s breathing. When we are nervous, frightened, or angry, our breathing is immediately affected, usually becoming short, fast, and shallow. Conversely, when we are relaxed and calm, our breathing is long, slow, and deep. Thus, our breathing often reflects our mental condition. If we consciously develop slow, calm, deep breathing, one result is a relaxed mind. Although the final aim of yogic breathing is not simply to calm the mind, this is an essential first step.

_

While priorities may differ between styles and teachers, when to inhale and exhale during asana is a fairly standardized practice element. Here three simple guidelines are offered for pairing breath with types of poses.

1. When bending forward, exhale.

When you exhale, the lungs empty, making the torso more compact, so there is less physical mass between your upper and lower body as they move toward each other. The heart rate also slows on the exhalation, making it less activating than an inhalation and inducing a relaxation response. Since forward bends are typically quieting postures, this breathing rule enhances the energetic effects of the pose and the depth of the fold.

2. When lifting or opening the chest, inhale.

In a heart-opening backbend, for instance, you increase the space in your chest cavity, giving the lungs, rib cage, and diaphragm more room to fill with air. And heart rate speeds up on an inhalation, increasing alertness and pumping more blood to muscles. Deep inhalation requires muscular effort that contributes to its activating effect. Poses that lift and open the chest are often the practice’s energizing components, so synchronizing them with inhalations takes optimum advantage of the breath’s effects on the body.

3. When twisting, exhale.

In twists, the inhalation accompanies the preparation phase of the pose (lengthening the spine, etc.), and the exhalation is paired with the twisting action. Posturally, that’s because as your lungs empty there’s more physical space available for your rib cage to rotate further. But twists are also touted for their detoxifying effects, and the exhalation is the breath’s cleansing mechanism for expelling CO2.

_

Belly Breathing:

Belly breathing allows you to focus on filling your lungs fully. It’s a great way to counteract shallow, stressed-out breathing:

•Sit in a comfortable position with one hand on your belly.

•With your mouth closed and your jaw relaxed, inhale through your nose. As you inhale, allow your belly to expand. Imagine the lower part of your lungs filling up first, then the rest of your lungs inflating.

•As you slowly exhale, imagine the air emptying from your lungs, and allow the belly to flatten.

•Do this 3-5 times.

This kind of breathing can help settle your nerves before a big test, sports game, or even before bed.

_

Yoga and diaphragm:

_

The diaphragm is one of the most unique muscles in the body and serves as the crucial actor in one of its most essential functions: breathing. What we might not always realize is that the diaphragm holds great significance beyond its essential role in facilitating the rhythm of breath. Unique in both form and function, the diaphragm creates an umbrella-like dome that sits over the abdominal organs, attaching to the inner surface of the ribs and lumbar vertebrae. When we inhale, the diaphragm flattens downward, putting gentle pressure on the belly’s organs, creating a vacuum that pulls air into the lungs. When we exhale, the diaphragm relaxes, releasing pressure on the organs, allowing the lungs to deflate. Without the diaphragm’s presence, the lungs would remain lifeless pieces of tissue. But with the magic of this special muscle’s movements, the lungs come to life and fill with oxygen for the body to use. On a physical level, this the diaphragm critically assists the body in the inhalation of oxygen and exhalation of carbon dioxide. On an energetic level, this process has deeper meaning. The act of breathing is evidence of our interdependent relationship with the world beyond ourselves. While breathing, we receive the oxygen from our environment and, in turn, offer carbon dioxide back out where it is absorbed by plants, trees and other microorganisms. From this perspective, breathing is more than just an act of individual survival; it is part of the ongoing processes of co-creation and communion with the world we inhabit. The yogi sees this process as an ongoing exchange of prana—the universal life force which flows through us all, driving our every action and sustaining life on our planet. This continuous exchange begins with our very first breath of life and ends with the last. From the moment we are born to the moment we transition, our breath is vital in making the world go round. For this remarkable act of interconnectedness, we have the diaphragm to thank. The unique muscle is located within the realm of the fourth chakra—anahata, the heart chakra (vide infra). This is the place in the body where primal and self-centric instincts begin to drive us toward connections with others, taking us beyond our physical, emotional and mental bodies. Additionally, the fourth chakra and diaphragm reside at the half-way point between the crown chakra and the first chakra regions. The inferior (lower) bodily functions are innately primitive, and the superior (upper) functions are esoteric and intellectual. The region of the fourth chakra then, becomes the point of balance between what exists within (for us personally) and our outward environment. Our ability to interact with the world and the quality of those interactions are evident in the way we breathe. The diaphragm, incredibly powerful yet sensitive enough to detect the subtleties of life, bears the imprints of any emotional, energetic and physical disturbances or highlights we experience. For instance, when we are tense, we tend to shorten or quicken the breath, but when we are relaxed or at ease, our breath is slower and more rhythmic. The breath can be considered a storehouse of memories, showcasing our interactions and personal habits in our breathing patterns.

_

Pranayama:

Pranayama is derived from the words “prana” (life-force or energy source) and “ayama” (to control). It is the science of breath control. This is an important part of Hatha Yoga because the yogis of old times believed that the secret to controlling one’s mind can be unlocked by controlling one’s breath. The practice of Pranayama can also help unleash the dormant energies inside our body. Pranayama is the fourth ‘limb’ of the eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga mentioned in verse 2.29 in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Many yoga teachers advise that pranayama should be part of an overall practice that includes the other limbs of Patanjali’s Raja Yoga teachings, especially Yama, Niyama, and Asana. The aim of pranayama is to inspire. infuse, control, regulate and balance the Prana Shakti (vital energy) in the body. You can do Pranayama 3 to 4 hours after meals. The most suitable and useful time for Pranayama is the morning hours on an empty stomach.

_

_

Our breath has a profound impact on our physiological states. Using breath to address imbalances of the nervous system is a very effective and powerful way to cultivate sattva. For example, did you know that simply extending the length of your exhales beyond the length of your inhales stimulates your parasympathetic nervous system (the “calm down” mechanism in your body)? On the other hand, taking breaths where your inhales are longer than your exhales has a stimulating (or rajasic) effect. Depending on how your body is feeling (overly stimulated or overly inert), you can choose the breath that brings you closer to balance.

_

Pranayama is the method of breath control. Proper breathing and awareness of the breath is very important. Swami Yogananda says, “Breath is the cord that ties the soul to the body”. Your breathing directly affects the mental states. Breathing exercises help to control bodily functions. A regular, deep breath enables one to feel calm and an irregular breath can make you feel anxious. Yoga Breathing helps to re- charge the cells in the body and re- energizes the brain cells; thus, the body is rejuvenated. Pranayama involves exhalation or rechaka pranayama, inhalation or puraka pranayama and retention of breath or kumbakha pranayama. It is a powerful tool to combat stress. Our mental states, feelings and bodily sensations affect the pattern of breathing. Positive thoughts cause regular breathing and negative thoughts cause uneven breathing. Correspondingly, in this stress filled lifestyle, it becomes imperative to practice yoga, correctly. Swami Svatmarama says, “By the faulty practice of pranayama the aspirant invites all kinds of ailments”. The aspirant should study the capacity of his lungs before embarking on the practice of pranayama. If he indulges in the wrong practice of pranayama, it will sap him of his energy. A wrong course of breath or over -enthusiasm could result in coughs, asthma, headaches, eye and ear pain.

_

Types of Pranayama:

•Quiet Breathing , Deep Breathing , Fast Breathing

• Tribandha and Pranayama

• Nadi Shuddhi Pranayama (Alternate nostril breathing – I)

•Anuloma – Viloma (Alternate Nostril Breathing – II)

•Suryan Bhedan Pranayama (Right Nostril Breathing)

• Ujjayi Pranayama

• Bhramari Pranayama

• Pranayama from Hatha Yoga

Surya Bhedan, Bhasrika, Ujjayi, Shitali, Sitkari, Bhramari, Murchha & Plavini Pranayama

_

Nadi Shodhana Pranayama (Alternate-Nostril Breathing):

This breath technique can help you feel more balanced and calm:

•Sit in a comfortable position.

•Place the thumb of your right hand on your right nostril. Tuck your first and middle fingers down and out of the way.

•As your right thumb gently closes your right nostril, slowly exhale through your left nostril, as you count to 5.

•Now, keeping your right thumb on the right nostril, slowly inhale through the left nostril, as you count to 5.

•Lift your thumb, use your ring finger to close your left nostril, and exhale through your right nostril for 5 counts. Then inhale through your right nostril as you slowly count to 5.

•Change back to putting your thumb over your right nostril. Lift your ring finger from your left nostril, and repeat the whole process — exhaling through your left nostril for 5 counts, then inhaling through the left nostril for 5 counts.

•Continue this pattern (exhale, inhale, change sides) for three more cycles.

This practice of alternating between the right and left nostrils as you inhale and exhale unblocks and purifies the nadis, which in yogic belief are energy passages that carry life force and cosmic energy through the body. While there is no clear scientific evidence to support these effects, one pilot study found that within seven days of practicing this technique, overactive nervous systems were essentially rebalanced.

_

Ujjayi Pranayama (Victorious Breath or Ocean Breath):

This classic pranayama practice, known for its soft, soothing sound similar to breaking ocean waves, can further enhance the relaxation response of slow breathing, says Patricia Gerbarg, MD, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at New York Medical College and co-author of The Healing Power of the Breath. Her theory is that the vibrations in the larynx stimulate sensory receptors that signal the vagus nerve to induce a calming effect. Inhale through your nose, then open your mouth and exhale slowly, making a “HA” sound. Try this a few times, then close your mouth, keeping the back of your throat in the same shape you used to make the “HA,” as you exhale through the nose.

_

Kumbhaka Pranayama (Breath Retention):

If you inhale fully and then wait 10 seconds, you will be able to inhale a bit more. Holding your breath increases pressure inside the lungs and gives them time to fully expand, increasing their capacity. As a result, the blood that then travels to the heart, brain, and muscles will be more oxygenated. Inhale, inflating the lungs as fully as possible. Hold the breath for 10 seconds. After 10 seconds, inhale a little more. Then hold it for as long as you can.

_

Kapalabhati Pranayama (Breath of Fire or Skull-Shining Breath):

This rapid breathing technique is energizing, and activates the sympathetic nervous system. In a study using EEG electrodes to measure brain activity, researchers found that Kapalabhati Pranayama increased the speed of decision-making in a test requiring focus. However for people already under stress, Breath of Fire is not a good idea because you’re throwing gasoline on the fire. To start, take a full, deep inhale and exhale slowly. Inhale again, and begin exhaling by quickly pulling in the lower abs to force air out in short spurts. Your inhalation will be passive between each active, quick exhalation. Continue for 25–30 exhalations.

_______

Meditation in yoga:

Yoga meditation is not actually a separate aspect of Yoga, due to the fact that Yoga is meditation. However, the phrase Yoga Meditation is being used here to discriminate between Yoga Meditation and the now popular belief that Yoga is about physical postures. Yoga or Yoga Meditation is a complete process unto itself, only a small, though useful part of which relates to the physical body. In the Yoga Meditation of the Himalayan tradition, one systematically works with senses, body, breath, the various levels of mind, and then goes beyond, to the center of consciousness.

_

An ordinary person may consider meditation as a worship or prayer. But it is not so. Meditation means awareness. Whatever you do with awareness is meditation. “Watching your breath” is meditation; listening to the birds is meditation. As long as these activities are free from any other distraction to the mind, it is effective meditation. Meditation is not a technique but a way of life. Meditation means ‘a cessation of the thought process’. It describes a state of consciousness, when the mind is free of scattered thoughts and various patterns. The observer (one who is doing meditation) realizes that all the activity of the mind is reduced to one.

_

Traditionally, the classical yoga texts, describe that to attain true states of meditation one must go through several stages. After the necessary preparation of personal and social code, physical position, breath control, and relaxation come the more advanced stages of concentration, contemplation, and then ultimately absorption. But that does not mean that one must perfect any one stage before moving onto the next. The Integral yoga approach is simultaneous application of a little of all stages together. Commonly today, people can mean any one of these stages when they refer to the term meditation. Some schools only teach concentration techniques, some relaxation, and others teach free form contemplative activities like just sitting and awaiting absorption. Some call it meditation without giving credence to yoga for fear of being branded ‘eastern’. But yoga is not something eastern or western as it is universal in its approach and application. With regular practice of a balanced series of techniques, the energy of the body and mind can be liberated and the quality of consciousness can be expanded. This is not a subjective claim but is now being investigated by the scientists.

_

Benefits of meditation:

– Stress relief

– Lowers high blood pressure and tension-related pain like headaches, insomnia, ulcers and joints pain too.

– Improves the mood, immunity, alertness and energy.

_

Sahaja yoga and mental silence:

Sahaja yoga meditation has been shown to correlate with particular brain and brain wave activity. Some studies have led to suggestions that Sahaja meditation involves ‘switching off’ irrelevant brain networks for the maintenance of focused internalized attention and inhibition of inappropriate information. A study comparing practitioners of Sahaja Yoga meditation with a group of non meditators doing a simple relaxation exercise, measured a drop in skin temperature in the meditators compared to a rise in skin temperature in the non meditators as they relaxed. The researchers noted that all other meditation studies that have observed skin temperature have recorded increases and none have recorded a decrease in skin temperature. This suggests that Sahaja Yoga meditation, being a mental silence approach, may differ both experientially and physiologically from simple relaxation. Sahaja meditators scored above peer group for emotional wellbeing measures on SF-36 ratings.

_

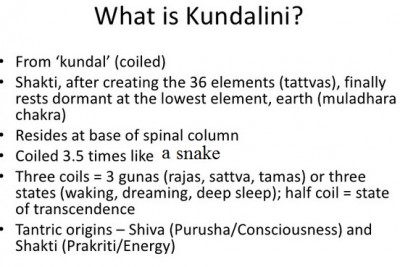

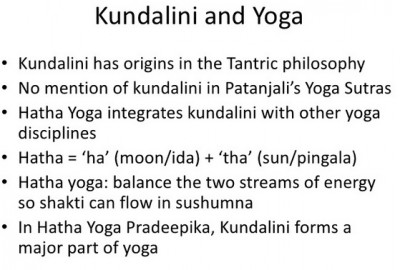

Kundalini yoga:

Kundalini yoga is the science of liberating the dormant potential energy in the base of the spine (kundalini). The definition of yoga in kundalini yoga is the union of the mental current (ida) and the pranic current (pingala) in the third eye (ajna chakra) or at the base chakra (muladhara chakra). This unifies duality in us by connecting body and mind, and leads to the awakening of spiritual consciousness. Kundalini yoga meditation research has found that there “appears to produce structural as well as intensity changes in phenomenological experiences of consciousness”, and that multiple regions of the brain are active.

_

Other types of meditation besides yoga:

There are different meditative techniques to suit different purposes:

– Mindful meditation

– Reflective meditation

– Mantra mediation

– Focused meditation

– Visualisation meditation

_

One of the most fascinating studies published on meditation is one from several years ago — but one that is good to keep in mind if you’re interested in mental health and brain plasticity. The study, led by Harvard researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), found that meditating for only 8 weeks actually significantly changed the brain’s grey matter — a major part of the central nervous system that is associated with processing information, as well as providing nutrients and energy to neurons. This is why, the authors believe, that meditation has shown evidence in improving memory, empathy, sense of self, and stress relief. “Although the practice of meditation is associated with a sense of peacefulness and physical relaxation, practitioners have long claimed that meditation also provides cognitive and psychological benefits that persist throughout the day,” Dr. Sara Lazar, a Harvard Medical School instructor in psychology said. “This study demonstrates that changes in brain structure may underlie some of these reported improvements and that people are not just feeling better because they are spending time relaxing.” In the study, 16 participants took a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program for 8 weeks. Before and after the program, the researchers took MRIs of their brains. After spending an average of about 27 minutes per day practicing mindfulness exercise, the participants showed an increased amount of grey matter in the hippocampus, which helps with self-awareness, compassion, and introspection. In addition, participants with lower stress levels showed decreased grey matter density in the amygdala, which helps manage anxiety and stress. “It is fascinating to see the brain’s plasticity and that, by practicing meditation, we can play an active role in changing the brain and can increase our well-being and quality of life,” Dr. Britta Holzel, an author of the study said.

_

Relaxation vis-à-vis meditation:

We often think of watching TV, sitting down with a cocktail or a good book, or simply vegging out as relaxing. But true relaxation is something that is practiced and cultivated; it is defined by the stimulation of the relaxation response. The relaxation response involves a form of mental focusing similar to meditation. Dr. Herbert Benson, one of the first Western doctors to conduct research on the effects of meditation, developed this approach after observing the profound health benefits of a state of bodily calm he calls “the relaxation response.” In order to elicit this response in the body, he teaches patients to focus upon the repetition of a word, sound, prayer, phrase, or movement activity (including swimming, jogging, yoga, and even knitting) for 10-20 minutes at a time, twice a day. Patients are also taught not to pay attention to distracting thoughts and to return their focus to the original repetition. The choice of the focused repetition is up to the individual. Some forms of conscious relaxation may become meditation, and many meditators find that their practice benefits from using a relaxation technique to access an inner stillness helpful for meditating. But while relaxation is a secondary effect of some meditation, other forms of meditation are anything but relaxing. Ultimately, it all comes down to the intention and purpose of the technique. All conscious relaxation techniques offer the practitioner a method for slowly relaxing all the major muscle groups in the body, with the goal being the stimulation of the relaxation response; deeper, slower breathing and other physiological changes help the practitioner to experience the whole body as relaxed.

____________

____________

Types and styles of yoga:

Yoga comes in many forms, but most classes contain two core components: poses and breathing. Poses are the different movements of yoga, ranging in difficulty from simply lying flat to physically challenging postures. As you perform the poses, you’ll carefully control your breathing and, depending on the type of yoga, meditate or chant. Hatha yoga is the basic form, slow-paced and suited for beginners. Other variations of yoga include the faster-paced ashtanga; Iyengar, which uses items such as straps or chairs to help with the poses; kundalini, which focuses heavily on chants and meditation; and Bikram, which you perform in a heated room.

_

Modern forms of yoga have evolved into exercise focusing on strength, flexibility, and breathing to boost physical and mental well-being. There are many styles of yoga, and no style is more authentic or superior to another; the key is to choose a class appropriate for your fitness level. Classes should be chosen depending on your fitness level and how much yoga experience you have. Types and styles of yoga may include: