Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

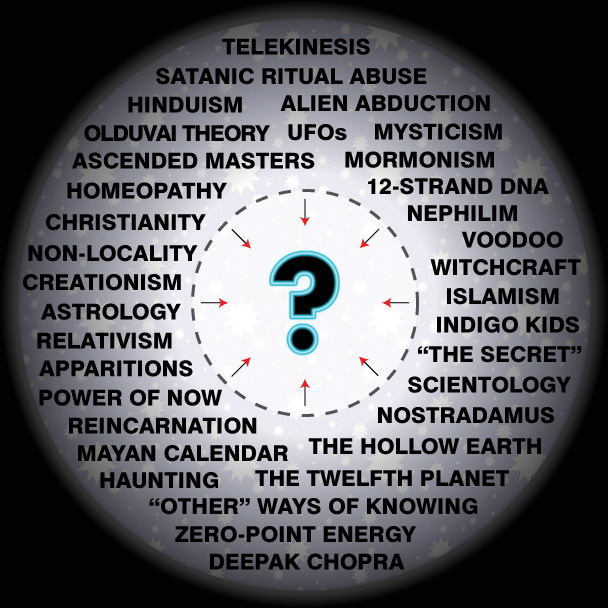

SUPERSTITIONS

SUPERSTITIONS:

_

_

Prologue:

I was traveling from Yanbu to Jeddah by plane and it was my first experience with Saudi Airline. Just before takeoff, as plane was standstill, I heard “Allāhu Akbar (الل أكبر)” [god is greatest] thrice and then plane took off. I never heard similar thing in Indian airlines planes praying Hindu Gods. Is Indian Airlines plane less safe than Saudi Airlines plane simply because a prayer is not recited before takeoff? Has superstition become pervasive in contemporary culture? Did you know that insects could be tried for criminal acts in pre-industrial Europe, that the dead could be executed, that statues could be subjected to public humiliation, or that it was widely accepted that corpses could return to life? What made reasonable educated men and women behave in ways that seem utterly nonsensical to us today? Strange histories present a serious account of some of the most extraordinary occurrences of European history. Throughout the ages, people have held ideas and events that have taken place which has baffled later societies. Religious disbelievers were thought deserving of death, insects were occasionally excommunicated, studying the biology of angels was a legitimate activity, and the pursuit of personal happiness was considered rather misguided as a life strategy. When science came along, it shattered people’s illusions and self-created fantasy worlds. Dr. Abraham T Kovoor said that “he who does not allow his miracles to be investigated is a crook, he who does not have the courage to investigate a miracle is gullible, and he who is prepared to believe without verification is a fool”. I am neither gullible nor fool, so I decided to write on superstitions. Mathematicians, as a rule, aren’t a superstitious lot, nor are they prone to mathematically irrational behavior.

_

_

A black cat crossing your path is said to bring bad luck. Do you get nervous when a black cat walks in front of you? Do you avoid walking under ladders? If you broke a mirror would you expect to get 7 years’ bad luck? If the answer is ‘yes’ to any of these questions then you are clearly a superstitious person. Humans seem to be a rather superstitious lot — whatever the subject, people are able to develop superstitions around it. People wear lucky clothing, carry lucky objects, and think that they have lucky numbers or days. A belief in superstition and the ability to control luck is widespread phenomenon. How do such superstitious beliefs develop and what causes them to be reinforced?

_

Superstitions cause those of us who would normally use common sense and rational thinking to act on that shred of doubt that lies in the back of each of our minds. One example of a superstition that has become common practice (and is also illegal to interfere with in some places) is that once it has begun, a funeral procession should never be interrupted or crossed. The result in breaking this custom can not only get you into trouble with the local police, but it is said that the soul of the deceased would be allowed to escape and transform into a hostile entity who could then direct his or her anger toward those gathered to honor the person’s memory. You are not really willing to risk trouble with the police, let alone being the cause of an angry spirit wreaking havoc on the mourners. So, like many others you choose to act on that little shred of doubt and go along with the superstition. It is, after all, much easier than chancing the alternative…isn’t it? Common sense and rational thinking, both tell us that’s ridiculous. Nothing like that could ever really happen. But, that little voice inside our heads that asks us “what if?” makes us choose to follow our little customs…just in case. This is one superstition that evidently carries a lot of clout considering it is enforced by the law.

_

Belief in superstition is extremely common in today’s modern society. Whether it is religious or secular notions of paranormal activities, most people hold some form of belief that goes beyond the current natural understandings of the world. We have to look at the children’s everyday reasoning for origin of such beliefs. Many aspects of adult belief appear in development during early childhood. While its influence may disappear with education and increased rational control, it may never entirely go away, especially if culture supports such beliefs. Moreover it may become more apparent at times when our ability to exercise rational control is weakened by stress, illness or diminished mental agility. Believing in the superstition also appears to offer comfort and control when we feel under threat. Superstitious beliefs have historically been attributed to the lingering influence of childhood understandings about the world (see Rozin & Nemeroff, 1990). There is knowledge that you get by experience (including what you have seen and discovered for yourself and anything you have been shown scientific proof of): this is called forensic knowledge. And then there are the things that you know to be true because people have told you. Most people get their earliest ideas of what is true from their parents. A little later we learn from teachers, and perhaps priests. If we get as far as high school we might see some actual scientific demonstrations, but even at high school, most of what we learn we accept because a teacher told us. None of us have time to discover everything for ourselves. You have never seen a lion kill a zebra – but you know they do. Most of what we know is what we have been told by people we rely on. Superstitions carry on from generation to generation based on this logic.

_

Definition of superstition:

_

Superstition is a belief in supernatural causality: that one event leads to the cause of another without any physical process linking the two events; a false conception of causality that contradicts natural science (e.g. astrology, omens, witchcraft, etc). It is an irrational belief that an object, action, or circumstance not logically related to a course of events influences its outcome. It is a belief, practice, or rite irrationally maintained by ignorance of the laws of nature or by faith in magic or chance. It is a belief, not based on human reason or scientific knowledge, that future events may be influenced by one’s behavior in some magical or mystical way. It is a belief in sign of things to come which is contrasted with fact, reality, science and truth. Some defined superstition as the belief in a casual relationship between an action, object, or ritual and an unrelated outcome. Such superstitious behavior can include actions like wearing a lucky jersey or using good luck charms.

_

Superstition (Latin superstitio, literally “standing over”; derived perhaps from standing in awe; used in Latin as an unreasonable or excessive belief in fear or magic, especially foreign or fantastical ideas, and thus came to mean a “cult” in the Roman empire) is a belief or notion, not based on reason or knowledge. The word itself comes from two Latin words. The first being “super” which means above and the second “stare” which means to stand. In the times of the Romans, those men who were lucky enough to have survived hand-to-hand combat were named “superstites”. This meant that they were lucky enough to be standing above others who had been killed in battle. The word is often used pejoratively to refer to supposedly irrational beliefs of others, and its precise meaning is therefore subjective. It is commonly applied to beliefs and practices surrounding luck, prophecy and spiritual beings, particularly the irrational belief that future events can be influenced or foretold by specific, unrelated behaviors or occurrences. To medieval scholars the word was applied to any beliefs outside of or in opposition to Christianity; today it is applied to conceptions without foundation in, or in contravention of, scientific knowledge and logical thought.

__

Superstition is a belief or notion, not based on reason or knowledge, in or of the ominous significance of a particular thing, circumstance, occurrence, proceeding, or the like. It is an irrational belief usually founded on ignorance or fear and characterized by obsessive reverence for omens, charms, etc Those who use the term imply that they have certain knowledge or superior evidence for their own scientific, philosophical, or religious convictions. An ambiguous word, it probably cannot be used except subjectively. With this qualification in mind, superstitions may be classified roughly as religious, cultural, and personal.

_

_

_

Superstitions receive considerable attention in several fields including popular psychology (Shermer 1998; Vyse 2000; Wheen 2004), philosophy (Scheibe & Sarbin 1965), abnormal psychology (Devenport 1979; Brugger et al. 1994; Shaner 1999; Nayha 2002) and medicine (Hira et al. 1998; Diamond 2001), which typically frame superstitions as irrational mistakes in cognition.

_

Superstition is an irrational belief or practice resulting from ignorance or fear of the unknown. The validity of superstitions is based on belief in the power of magic and witchcraft and in such invisible forces as spirits and demons. A common superstition in the Middle Ages was that the devil could enter a person during that unguarded moment when that person was sneezing; this could be avoided if anyone present immediately appealed to the name of God. The tradition of saying “God bless you” when someone sneezes still remains today. We have all seen plenty of superstitions. There are the superstitions that a rabbit’s foot or a four-leaf clover brings good luck. There are superstitions that breaking a mirror or seeing a black cat bring bad luck.

_

According to Webster’s dictionary, superstition is any belief that is inconsistent with the known laws of science or with what is considered true and rational; especially such a belief in omens, the supernatural, etc. Halloween is traditionally the time when common superstitions, folklore, myths and omens carry more weight to those who believe. Superstition origins go back thousands of years ago. Beliefs include good luck charms, amulets, bad luck, fortunes, cures, portents, omens, predictions, fortunes and spells. Bad fallacies far outweigh the good, especially around Halloween when myths run rampant. When it comes right down to it, many people still believe that omens can predict our destiny and misfortune — particularly for the worse. Since the dawn of history people have used charms and spells to try to control their environment, and forms of divination to try to foresee the otherwise unpredictable chances of life. Many of these techniques were called “superstitious” by educated elite.

_

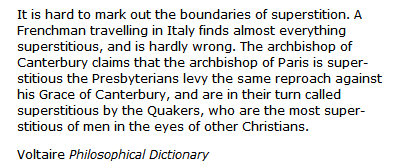

For centuries religious believers used “superstition” as a term of abuse to denounce another religion that they thought inferior, or to criticize their fellow-believers for practicing their faith “wrongly.” From the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment, scholars argued over what ‘superstition’ was, how to identify it, and how to persuade people to avoid it. Learned believers in demons and witchcraft, in their treatises and sermons, tried to make ‘rational’ sense of popular superstitions by blaming them on the deceptive tricks of seductive demons. Every major movement in Christian thought, from rival schools of medieval theology through to the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Enlightenment, added new twists to the debates over superstition. Protestants saw Catholics as superstitious, and vice versa. Enlightened philosophers mocked traditional cults as superstitions. Eventually, the learned lost their worry about popular belief, and turned instead to chronicling and preserving ‘superstitious’ customs as folklore and ethnic heritage.

_

How do superstitions get started?

The growth of superstition came out of ancient times, before higher education and scientific reason took hold in logical minds. As it was then, so it is now that the ignorance of not knowing how something works or happens causes some people to assume there had to have been some divine intervention rather than something of natural origin. Examples of such inexplicable natural occurrences would be:

Thunder

Lightening

Earthquakes

Tornados

Tidal waves

Hurricanes

Fires

Of course, each of these natural phenomena has long since been explained away by scientific reason. But, imagine living in times before such knowledge existed. It isn’t hard at all to understand where superstitions developed from and that people believed these natural disasters were caused by an angry, supreme being of some sort. Superstitions began long ago with primitive man, who was looking for answers to natural phenomena such as lightning, thunder, eclipses, birth and death. Since he lacked knowledge of the laws of nature, he developed a belief in unseen spirits. He observed the animals and their seemingly sixth sense when it came to awareness of danger and imagined that spirits were whispering secret warnings to them. And since his daily existence was full of so many hardships, he assumed the world was populated with more vengeful spirits than with beneficent ones. That would explain why most superstitious beliefs involve ways to protect ourselves from evil. To protect himself in such an uncertain world, ancient man adopted various superstitious rituals in an effort to impose human will on chaos. Over a period of time, superstitious beliefs have rooted themselves firmly in our society, so much so that it is virtually impossible for the person to ignore them. They have made a place for themselves in all the walks of life, including politics and sports. Politicians resorting to the astrological predictions are not at all rare. On the other hand, examples of superstitions in sports include cricketers carrying a colored handkerchief in their pocket, or soccer players putting their right foot first when they enter the field. Such superstitious practices are found all over the world.

_

Superstitions began centuries ago when our ancestors tried to explain mysterious circumstances or events as best as they could with the knowledge they had. For instance, before the development of science explained such strange things as why mirrors show our reflections or why shadows appear when it’s sunny, ancient people reasoned that a shadow or reflection was part of their soul. If someone broke something onto which the shadow or reflection appeared, people believed that their soul was harmed. Therefore, when a person broke a mirror it was considered unlucky or harmful. Today we know that reflections and shadows are not part of our souls, but if someone still believes it is bad luck to break a mirror, they are said to be superstitious. So a superstition is a belief or practice that people cling to even after new knowledge or facts prove that these silly beliefs are untrue.

__

For many centuries it was believed that eclipses of the sun and moon were prophetic of pestilence or famine, and that comets foretold the death of kings, or the destruction of nations, the coming of war or plague. All strange appearances in the heavens — the Northern Lights, circles about the moon, sun dogs, and falling stars — filled our intelligent ancestors with terror. They fell upon their knees — did their best with sacrifice and prayer to avoid the threatened disaster. Their faces were ashen with fear as they closed their eyes and cried to the heavens for help. The clergy, who were as familiar with God then as the orthodox preachers are now, knew exactly the meaning of eclipses and sun dogs and Northern Lights; knew that God’s patience was nearly exhausted; that he was then whetting the sword of his wrath, and that the people could save themselves only by obeying the priests, by counting their beads and doubling their subscriptions. Earthquakes and cyclones filled the coffers of the church. In the midst of disasters the miser, with trembling hands, opened his purse. In the gloom of eclipses thieves and robbers divided their booty with God, and poor, honest, ignorant girls, remembering that they had forgotten to say a prayer, gave their little earnings to soften the heart of God. Now we know that all these signs and wonders in the heavens have nothing to do with the fate of kings, nations or individuals; that they had no more reference to human beings than to colonies of ants, hives of bees or the eggs of insects. We now know that the signs and eclipses, the comets, and the falling stars, would have been just the same if not a human being had been upon the earth. We know now that eclipses come at certain times and that their coming can be exactly foretold.

_

First documented superstitious belief:

Archeologists believe it was Neanderthal man who produced the first superstitious (and spiritual) beliefs as far back as 50,000 years ago. They were apparently the first humans to bury their dead rather than just abandoning them. They obviously believed in an afterlife as they buried their loved ones with ritual funerals and interred the bodies with food, weapons and fire charcoals for use in the afterlife.

_

The true origin of superstition is to be found in early man’s effort to explain Nature and his own existence; in the desire to propitiate Fate and invite Fortune; in the wish to avoid evils he could not understand and in the unavoidable attempt to pry into the future. From these sources alone must have sprung that system of crude notions and practices still obtaining among savage nations; and although in more advanced nations the crude system gave place to attractive mythology, the moving power was still the same; man’s interpretation of the world was equal to his ability to understand its mysteries no more, no less. For this reason the superstitions which, to use a Darwinian word, persist, are of special interest, as showing a psychological habit of some importance. The first note in all superstitions is that of ignorance. Ignorance exists in several varieties, and one of them has to do not with the future, but with the well-established present; in other words, an accepted doctrine may be based on a misinterpretation of the facts. As Trenchard remarks in his Natural History of Superstition, “Man’s curiosity is in excess of his capacity to interpret Nature and life.” Thus early man attributed a living spirit to everything–to his fellows, to the lower animals, to the trees, the mountains, and the rivers. Probably these conclusions were as good as his intelligence would allow, but they became the mental stock-in-trade of all races, and were handed down from one generation to another, constituting a barrier to be broken down before newer and truer ideas of life could prevail. And the same contention applies equally to the superstition of the moment. Allied with ignorance is fear, which is the second element calling for notice. Fear, too, has its varieties, some of them both natural and justifiable. It is irrational fear which forms the bogey of superstition. The misfortune of early man was to have experiences more numerous and subtle than he could understand; to his power of analysis they were altogether unyielding; and yet his unrestrained imagination demanded a working theory of some kind, and he got one, grounded in ignorance and fear. An earthquake is a phenomenon calculated to strike terror into the heart of all but the strongest man; no wonder then that the primitive mind invented all sorts of ideas about spirits of the under world, and ascribed to gloomy caverns the possession of dragons and other fearsome enemies of the race. The thunder, the lightning and the tempest; the blight which spoiled the sources of food; the sudden attack of mysterious sickness, and a hundred other fatalities were to him more than merely natural forces busily employed in working out their natural destiny; they were powers to be appeased. That is the third note of the superstitious mind; its effort to appease intelligent and semi-intelligent forces by suitable beliefs, rites, ceremonies, and penances. Whenever ignorance and fear bring about a sense of danger, a way has to be found, a way to escape. Superstitions provided a way to escape by appeasing hidden forces.

_

Superstitions are beliefs or practices for which there appears to be no rational substance. It is a term designated to these beliefs that result from ignorance and fear of the unknown. Those who use the term imply that they have certain knowledge or superior evidence for their scientific, philosophical, or religious convictions. An ambiguous word, it probably cannot be used except subjectively. Ignorance of natural causes leads to the belief that certain striking phenomena express the will or the anger of some invisible overruling power, and the objects in which such phenomena appear are forthwith deified. Also many superstitious practices are due to an exaggerated notion or a false interpretation of natural events, so that effects are sought which are beyond the efficiency of physical causes. Curiosity also with regard to things that are hidden or are still in the future plays a considerable part, example, in the various kinds of divination. With this qualification in mind, superstitions may be classified roughly as religious, cultural and personal. Superstitions have come a long way in history and have been evolved in this process. Every known civilization that ever existed on the planet had something common in them; these were the myths and superstitions that were a crucial part of their cultures. All religious beliefs and practices may seem superstitious to the person without religion. Superstitions that belong to the cultural tradition are enormous in their variety. Nearly all persons, in nearly times, have held, seriously, irrational beliefs concerning methods of warding off ill or bringing good, foretelling the future, and healing & preventing sickness & accidents. Even people who claim they have no superstitions are likely to do a few things they cannot explain.

_

Superstitions are born out of one or all of the following circumstances:

Ignorance

Custom

Fear

_

Superstitions are contagious:

One reason must be sought in the fact that superstition has always been contagious. This is amusingly set forth by Bagehot in his Physics and Politics, although probably India contains more mysteries than he allowed:-“In Eothen there is a capital description of how every sort of European resident in the East–even the shrewd merchant and the ‘post-captain with his bright, wakeful eye of command’–comes soon to believe in witchcraft, and to assure you in confidence that ‘there is really something in it;’ he has never seen anything convincing himself, but he has seen those who have seen those who have seen those who have seen; in fact he has lived in an atmosphere of infectious belief, and he has inhaled it.” If this is true now, it must have been more profoundly true in past centuries. The presence everywhere of the same superstition, though in different forms, is a testimony to the power of contagious fears. Children brought up in the atmosphere of credulity do not often rise above it. White in his Selborne observes:-“It is the hardest thing in the world to shake off superstitious prejudices; they are sucked in as it were with our mother’s milk; and, growing up with us at a time when they take the fastest hold and make the most lasting impressions, become so interwoven with our very constitutions, that the strongest sense is required to disengage ourselves from them. No wonder, therefore, that the lower people retain them their whole lives through, since their minds are not invigorated by a liberal education, and therefore not enabled to make any efforts adequate to the occasion”.

_

Superstitions vis-à-vis miracles:

Whether miracles and superstitions are two sides of the same coin or different coins altogether need to be discussed.

First, what is superstition?

1. To believe in spite of evidence or without evidence.

2. To account for one mystery by another.

3. To believe that the world is governed by chance or caprice.

4. To disregard the true relation between cause and effect.

5. To put thought, intention and design back of nature.

6. To believe that mind created and controls matter.

7. To believe in force apart from substance, or in substance apart from force.

8. To believe in miracles, spells and charms, in dreams and prophecies.

9. To believe in the supernatural.

__

What is miracle?

An act performed by a master of nature without reference to the facts in nature. This is the only honest definition of a miracle. If a man could make a perfect circle, the diameter of which was exactly one-half the circumference, that would be a miracle in geometry. If a man could make two plus two equal to five, that would be a miracle in arithmetic. If a man could make a stone, falling in the air, pass through a space of ten feet the first second, twenty-five feet the second second, and five feet the third second, that would be a miracle in physics. If a man could put together hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen and produce pure gold, that would be a miracle in chemistry. If a minister were to prove his creed, that would be a theological miracle. If Congress by law would make fifty cents worth of silver worth a dollar, that would be a financial miracle. To make a square triangle would be a most wonderful miracle. To cause a mirror to reflect the faces of persons who stand behind it, instead of those who stand in front, would be a miracle. To make echo answer a question would be a miracle. In other words, to do anything contrary to or without regard to the facts in nature is to perform a miracle. We believe that all things act and are acted upon in accordance with their nature; that under like conditions the results will always be substantially the same; that like ever has and ever will produce like. Miracles are not simply impossible, but they are unthinkable by any man capable of thinking. A rational, intelligent and scientific man cannot believe that a miracle ever was, or ever will be performed. Ignorance is the soil in which belief in miracles grows. So in a nutshell, to believe in miracle is superstitious but all superstitions are not miracles.

_

Superstition and magic spell:

Superstitions differ from magic spells in that the former are generally passive if/then constructs while the latter contain formulae, recipes, petitions, prayers, and enchantments for effecting future outcomes by means of supernatural, symbolic, and perhaps non-causal activities. People who otherwise accept scientific de-mystification of the supernal world and do not consider themselves to be occultists or practitioners of magic, still may consider that it is “better to be safe than be sorry” and observe or transmit some or many of the superstitions endemic to their cultures.

_

Paranormal:

Paranormal is a general term that designates experiences that lie outside “the range of normal experience or scientific explanation” or that indicates phenomena understood to be outside of science’s current ability to explain or measure. The definition implies that the scientific explanation of the world around us is the ‘normal’ part of the word and ‘para’ makes up the above, beyond, beside, contrary, or against part of the meaning. Thousands of stories relating to paranormal phenomena are found in popular culture, folklore, and the recollections of individual subjects. Notable paranormal beliefs include those that pertain to ghosts, extraterrestrial life, unidentified flying objects, and cryptids. From the scientific point of view, belief in paranormal is superstitious.

_

Superstition vis-à-vis luck:

No discussion on superstition can be held without mentioning luck.

So what is luck anyway?

Luck is a sign of imperfection in life.

The more you achieve perfection, the less you need luck. The more you are imperfect, the more you need luck. One example is sufficient. Out of millions of buyer’s of lottery, only one wins a jackpot. We call him lucky. Why? Because out of millions of lottery sold, only one had winning number and that man got it just by chance. What was the chance? One in million. So remaining 999,999 people were not lucky but their money went to this lucky man. In other words, million people contributed little money each to make this lucky man rich overnight. We are so imperfect. Instead, if all money was invested in stock market and if that stock has grown markedly, probably all million people would have benefited albeit not becoming rich overnight. Now if that lucky man is superstitious, he would believe that since he was wearing a green shirt at the time of buying a lottery, he won. So whenever he buys lottery, he makes sure that he wears green shirt no matter whether he wins lottery again. He may never win a jackpot again but he will wear green shirt every time he buys lottery. This is how luck is correlated with superstition.

_

Another example, flipping a coin at the start of a sporting event may determine who goes first. If you win the toss, you are lucky. Again we are so imperfect. If we knew all variables in flipping coin e.g. force used by person flipping coin, weight of coin, gravity, air resistance, atmospheric pressure, levelness of land on which coin falls etc; and if we knew how all variables would interact with each other, we could scientifically predict how coin will fall and on which side. But since we are ignorant and imperfect, we create luck and give credit/discredit to luck. Now if a cricket captain is superstitious and has won the toss and had red handkerchief in pocket, he will believe that red handkerchief made him lucky to win the toss. So every time at the toss of coin, that cricket captain will keep red handkerchief in pocket. This is how luck is correlated with superstition.

_

Luck refers to that which happens to a person beyond that person’s control. This view incorporates phenomena that are chance happenings, a person’s place of birth for example, but where there is no uncertainty involved, or where the uncertainty is irrelevant. Of course, luck will always exist whenever there is uncertainty associated with lack of control. Within this framework one can differentiate between three different types of luck:

1. Constitutional luck, that is, luck with factors that cannot be changed. Place of birth and genetic constitution are typical examples.

2. Circumstantial luck – with factors that are haphazardly brought on. Accidents and epidemics are typical examples.

3. Ignorance luck, that is, luck with factors one does not know about but can be identified only in hindsight. Typical example is already discussed above –a person winning jackpot believes that green shirt is responsible to bring luck to him.

_

Luck or fortuity is good fortune which occurs beyond one’s control, without regard to one’s will, intention, or desired result. There are at least two senses people usually mean when they use the term, the prescriptive sense and the descriptive sense. In the prescriptive sense, luck is the supernatural and deterministic concept that there are forces (e.g. gods or spirits) which prescribe that certain events occur very much the way the laws of physics will prescribe that certain events occur. It is the prescriptive sense that people mean when they state that they “do not believe in luck”. In the descriptive sense, luck is merely a name we give to events after they occur which we find to be fortuitous and perhaps improbable.

_

A rationalist approach to luck includes the application of the rules of probability and an avoidance of unscientific beliefs. The rationalist feels the belief in luck is a result of poor reasoning or wishful thinking. To a rationalist, a believer in luck who asserts that something has influenced his or her luck commits the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” logical fallacy: that because two events are connected sequentially, they are connected causally as well. There is also a series of spiritual or supernatural beliefs regarding fortune. These beliefs vary widely from one to another, but most agree that luck can be influenced through spiritual means by performing certain rituals or by avoiding certain circumstances. A game may depend on luck rather than skill or effort. Many countries have a national lottery. Individual views of the chance of winning, and what it might mean to win, are largely expressed by statements about luck. “Leaving it to chance” is a way of resolving issues. Most cultures consider some numbers to be lucky or unlucky.

_

What causes Good Luck?

From centuries people have believed in good fortune and widely agree that luck can be influenced through spiritual means by performing certain rituals or by avoiding certain circumstances. One such activity is prayer, a religious practice in which this belief is particularly strong. Many cultures and religions worldwide place a strong emphasis on a person’s ability to influence their fortune by ritualistic means, sometimes involving sacrifice, omens or spells. Others associate luck with a strong sense of superstition, that is, a belief that certain taboo or blessed actions will influence how fortune favors them for the future. List of Good Luck Superstitions includes:

•If you sneeze it means someone is missing you.

• If your right hand itches, you will earn money.

• If you find a four-leaf clover, you will have good luck.

• If you see a horseshoe which was lost, you will have good luck.

• If you throw rice on a new bride and groom, they will have so many children.

• If you dream about a white cat, you will have good luck.

• If your right ear itches, someone is speaking well of you.

• You can hang up garlic in your house for good luck.

• If you put a mirror just across the door, before you will have good luck.

• If you put the sugar into the cup first, the tea, you will have good luck.

•If you step on your shadow, it brings you luck.

• If you blow out all the candles on your birthday cake in one blow, you will get whatever you want.

• A lock of hair from a baby’s first haircut should be kept for good luck.

_

What causes Bad Luck?

To begin with, we have to admit that sometimes events are just random, or at least with causes beyond our ability to understand at the moment. Blaming and making excuses are ways to avoid taking responsibility for one’s own life. It is a common trait among majority of the people. Many people point out the activities and the circumstances for their bad luck, but they cannot see what their own contribution to their situation is. Blaming and excuse makes a terrible approach to life. It eventually makes looking for causes outside the control of oneself automatic. It is difficult for such a person to ever recognize the personal changes they need to make. But the habit of concentrating on who or what is to blame doesn’t motivate a person to do what is necessary. List of Bad Luck Superstitions includes:

• If you break a mirror, it will bring you seven years of bad luck.

• If you walk under a ladder, you will have bad luck.

• If a dog howls at night, death is near.

• If you drop a dishcloth, you will have bad luck.

• If you eat from the pot, it will rain at your wedding ceremony.

• It is bad luck to see an owl in the sunlight.

• If a bat flies into your house it is bad luck.

•Many people believe Friday 13th is an unlucky day.

• If a black cat crosses your path you will have bad luck.

• It is bad luck to open an umbrella in the house.

• If you break a mirror you will have 7 years of bad luck.

• If you walk under a ladder, you will have bad luck.

• It is bad luck to let milk boil over.

•Cutting your nails after sunset will bring bad luck.

• If you dream about a dog, you will have a lot of enemies.

•You have to get out of the bed on the same side you got in on or you will have bad luck.

•It is unlucky to rock an empty rocking chair

•f you open an umbrella indoors, it brings you bad luck.

•If your left hand itches, you will lose money.

• If you sleep with your feet towards the door, a nightwalker will steal your soul.

• If you whistle at night, a nightwalker will come to your home.

• When a cat sneezes three times indoors, it will rain in 24 hours.

• If an owl hoots in your garden, it brings you bad luck.

_

How to increase luck:

There are ways of increasing one’s luck. One trick is to simply stay optimistic. A way how to do this is to keep a journal everyday and write down everything that happened and hypothesize all the good that will come out of it. Do not look for bad things. Try not to even think about them. Eventually, this will begin happening automatically. As soon as something happens, the thoughts of good will automatically pop up. This will increase confidence and optimism. Also, hanging around optimist people can help, some of their outlooks may rub off. My view is that best way to avoid luck is to strive for perfection in whatever field you work. Please work hard honestly, sincerely and without corruption, and you will find that you do not need luck.

_

Luck vis-à-vis human error:

Human error is inevitable because human error is directly proportional to human performance variability, greater the variability, more chance of error and vice versa. Luck is a sign of imperfections in life and therefore luck & human error are two sides of the same coin [read my article on human error]. One example is sufficient. You are walking on a street and a car is coming on the same street. Would you be knocked down by that car? If that car driver makes a mistake, the car may hit you. Now look at the scenario from another perspective. You would be unlucky if that car hit you as there are so many people walking on the same street at the same time and only you were hurt. So human error and luck are the two sides of the same coin of life; the life which is uncertain, variable and imperfect; and it is so because we do not know all variables and how these variables would act & interact according to which law governing them. By this logic, God is defined as an entity who knows all variables of the universe and knows how these variables would act & interact following laws prescribed for them in such a way that creates current existence and accurately predicts future existence. I personally believe that such an entity does not exist.

_

Superstition vis-à-vis human error:

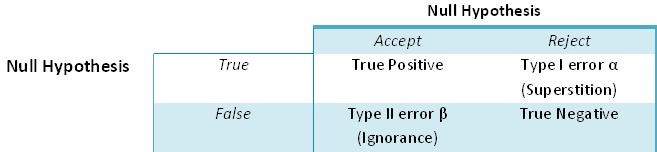

Since luck & human error are connected, and since luck & superstitions are connected, superstitions would be connected to human errors. So a brief review of errors is warranted. Errors are of types I and II: Type I error, also known as “false positive” occurs when we are observing a difference when in truth there is none, thus indicating a test of poor specificity. Type II error, also known as “false negative” is the error of failing to observe a difference when in truth there is one, thus indicating a test of poor sensitivity. For example: in justice system, Type I errors means an innocent person goes to jail and Type II errors means a guilty person is set free. People find type II errors disturbing but not as horrifying as type I errors. A type I error means that not only has an innocent person been sent to jail but the truly guilty person has gone free. In a sense, a type I error in a trial is twice as bad as a type II error. Needless to say, the justice system ought to put lot of emphasis on avoiding type I errors.

_

A null hypothesis states that X does not cause Y. If you think X does cause Y then the burden of proof is on you to provide convincing experimental data to reject the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis also means that the burden of proof is on the person asserting a positive claim, not on the skeptics to disprove it. The principle of positive evidence states that you must have positive evidence in favor of your theory and not just negative evidence against rival theories.

_

_

We can look at the decision logic to believe in superstition based on a balancing act between Type I error (superstition) and Type II error (ignorance). If superstition is indeed true and you reject it, it is Type I error. If superstition is indeed false and you accept it, it is Type II error. I already discussed earlier that Type I error is worse than Type II error. Whenever people take action, they need to decide the probability of mistake they are willing to accept. When people try to lower their superstitions (a lower α), they will have to increase the possibility of ignorance (a higher β). Therefore, it might make sense to lower the chance of ignorance and accept a higher degree of superstition. For instance, you will avoid picking up an unlucky number (higher α) just in case it is true (lower β). It is noteworthy to mention that this is consistent with the heuristic decision making process – when one needs to make a quick decision, his or her brain will take a mental short-cut and adopt a safer route. A classic example is that if you hear something that sounds like a tiger in a forest, you will just run instead of assessing the probabilities of every possible outcome because if it is indeed tiger, you will be killed and if it is not tiger and you ran away, no harm is done anyway. Better safe than sorry (vide infra).

_

Superstition may be seen in various contexts, for example; as error, as subconscious, as conditioned response, as social phenomenon, as mode of thinking, as uncertainty, as habit, as luck controller, as coincidental association etc (vide infra).

_

Prevalence of superstitions:

Lucky charms statistics show that three out of four people carry good-luck charms, whether they admit it or not. Most students say they perform better on tests when they wear lucky socks, special jewelry, or some other lucky charm. In 1998, the researchers in U.K. sent out a questionnaire asking respondents to write down any superstitions they knew, in order to assess the current repertoire; researchers made clear that they were not asking what respondents believed, only what they knew of. Ten spaces were provided, and respondents were told they could add more items if they wished. The first 215 replies received showed this was indeed the case; few of the items reported were uncommon, and many appeared time and again. It seemed unlikely that further results will change the basic pattern. The following summary gives the number of times the ‘Top Ten’ items were mentioned, the percentage (of 215) this represents, and the date of the first known reference to the belief in Britain, taken from Opie and Tatem.

_

| 1. | 178 | 83% | Unlucky to walk under a ladder (1787) |

| 2. | 144 | 67% | Lucky/Unlucky to meet black cat (1620) |

| (More respondents said ‘lucky’ than ‘unlucky’; several commented ‘don’t know which’) | |||

| 3. | 117 | 54% | Unlucky to break a mirror (1777) |

| (Most specified ‘seven years’ bad luck’) | |||

| 4. | 102 | 47% | Unlucky to see one magpie, lucky to see two, etc. (c.1780) |

| 5. | 94 | 44% | Unlucky to spill salt (1584?) |

| (Most mentioned throwing a pinch over the shoulder to counteract bad luck) | |||

| 6. | 85 | 39% | Unlucky to open umbrella indoors (1883) |

| 7. | 78 | 36% | Thirteen unlucky/Friday the thirteenth unlucky (1711/1913) |

| (These related items were given in about equal numbers; some gave both) | |||

| 8. | 76 | 35% | Unlucky to put shoes on table (1869) |

| (Most specified new shoes) | |||

| 9. | 45 | 21% | Unlucky to pass someone on the stairs (1865) |

| 10. | 34 | 16% | Lucky to touch wood (1877) |

_

_

_

_

_

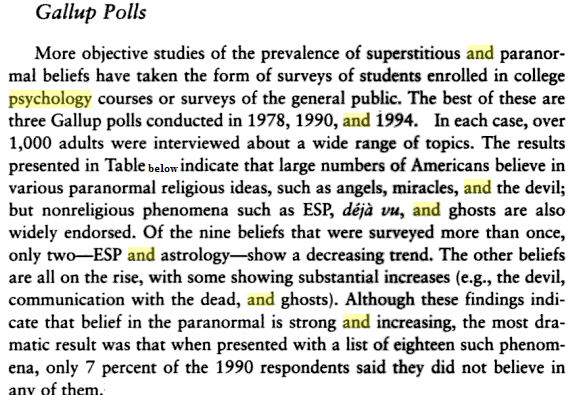

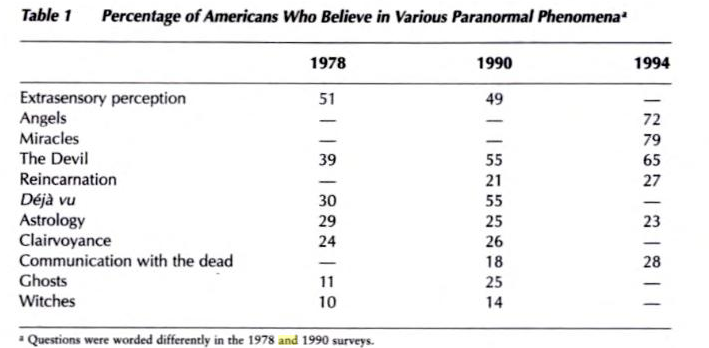

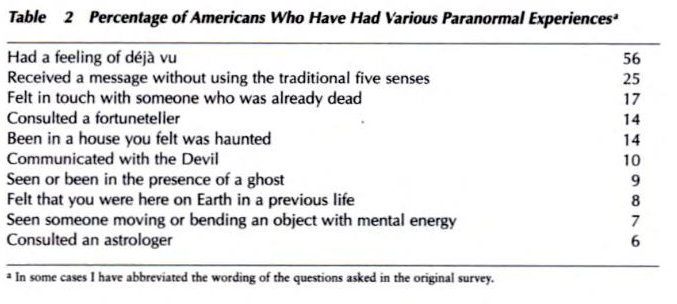

A recent Gallup Poll found that 53% of Americans were at least ‘a little’ superstitious and a further 25% admitted they were ‘very superstitious’.

_

Another survey revealed the UK’s top superstitions and the percentage of people endorsing each of them:

1: Touching wood – 86%

2: Crossing fingers – 64%

3: Walking under a ladder – 49%

4: Breaking a mirror – 34%

5: Worried about the number 13 – 25%

6: Carrying a lucky charm – 24%

These are surprisingly high figures, and indicate that superstition is alive and well in modern day Britain. Indeed, amazingly, 86% of Brits said that they carried out at least one of these superstitious behaviors. Even scientists are not immune from superstition – for example, 15% of people with a science background said that they feared the number 13.

_

As far as largest democracy India is concerned, 90% people believe in astrology and many mainstream TV channel telecast astrological prediction daily. Of course, astrology is a superstition but India also hosts plenty of superstitions right from praying for rain every year to witchcraft. Superstitions exist in every country, every religion, every culture and every civilization.

_

Superstitions and gender:

Generally speaking, women are more superstitious than men. Women are significantly more superstitious than men: 51% of women said that they were very/somewhat superstitious compared to just 29% of men. When it came to individual superstitions, far more women than men cross their fingers (women: 75% v/s men: 50%), and touch wood (women: 83% v/s men: 61%). These findings replicate other research concerned with belief and gender, and may be due to women having lower self-esteem and less perceived control over their lives, than men. Women may also experience more anxiety, or at least, more women than men seek help for anxiety problems. Although personality variables are not a strong factor in developing superstition, there is some evidence that if you are more anxious than the average person you’re slightly more likely to be superstitious. Our locus of control can also be a factor contributing to whether or not we are superstitious. If you have an internal locus of control, you believe that you are in charge of everything; you are the master of your fate and you can make things happen. If you have an external locus of control, you’re sort of buffeted by life, and things happen to you instead of the other way around. People with external locus of control are more likely to be superstitious, possibly as a way of getting more power over their lives. Part of the reason why women are more superstitious than men is that women feel, even in today’s modern society, that they have less control over their fate than men do. There is also another factor. This has a lot to do with the lack of education among women especially in developing country like India.

__

Age and superstitions:

People become less superstitious as they age: 59% of people aged 11-15 said they were superstitious, compared to 44% of people aged between 31-40 and just 35% of the over 50s. These findings do not suggest that superstitious behavior and beliefs will be consigned to the past. Instead, they are strongly held by the younger members of society.

_

Even without adequate definition, one can identify some of the patterns, formulas, and basic principles controlling modern superstitions.

(a) They aim to ‘accentuate the positive/eliminate the negative’: do this for good luck, avoid that to prevent bad luck.

(b) Luck can be influenced, but not completely controlled.

(c) Do not transgress category boundaries, for example wild flowers or open umbrellas (outdoor items) should not be indoors.

(d) To seem too confident about the future is ‘tempting fate’ and attracts retribution—‘Don’t count your chickens before they hatch’.

(e) Some days or times are lucky or (more usually) unlucky; they vary in frequency (midnight, Friday, Friday the thirteenth, Holy Innocents Day), and can be individual—‘Tuesday is always my lucky day’.

(f) Something that begins well (or badly) will probably continue that way.

(g) As in magic, things once physically linked retain a link even when separated (birds using your hair in their nests will give you a headache).

(h) Evil forces exist and are actively working to harm you; these may be impersonal, or concentrated in humans (witches, ill-wishers) or other beings (devils, fairies).

(i) Certain things, words, or actions have powerfully negative effects, and must be avoided or counteracted (taboo).

(j) Anything sudden, unexpected, or unusual can be seen as an omen, usually of misfortune. However, many superstitions do not fit these categories, and individuals can invent their own (e.g. ‘Must get back to bed before the toilet stops flushing’).

_

All civilizations have their respective superstitions. While some believe in ghosts and sorcery others resort to numerology and spirits. The number 13 is considered very unlucky by the western world because of legends of Christ linked with it. Many a time it is just the psychology that affects us. When one is increasingly made to believe that a particular thing is not right, the mental science of the person tend to make them believe so. The eastern world has its own share of superstitions. Hooting of owls and howling of dogs augurs impending death. Also the sites of a priest or sneezing before commencing for a journey are considered very ominous. Experiments are definitely on to find out whether man has a soul that leaves him after his death. The existence of ghosts and their mystic powers are still to be proved. One cannot however reject superstitions that have a scientific backing to then. For instance application of sandalwood on the forehead may be a superstitious activity but sandalwood also keeps the forehead cool and soothes the brain. In today’s scientific world it is necessary that we do not blindly follow all the superstitions that are handed over to us by our ancestors. We are modern both in terms of outlook & age and we must have a judicious approach and look for more logical reasons behind every superstition before accepting it. Only then will we be able to give up the beliefs that have no rationality in today’s life. It is only this way that we can lead a life befitting the citizens of the modern era.

_

Superstition paradigm:

_

Positive and negative superstitions:

Black cats can bring bad luck. If you break a mirror, you will have bad luck and the number13 is unlucky. All of these items refer to beliefs that can be classified as negative superstitions. That is, they all reflect the notion that certain behaviors (e.g., breaking a mirror) or omens (e.g., seeing a black cat) are magically associated with unlucky and potentially harmful consequences. Given that this is the case, it is perhaps not surprising that, as noted above, scores on this sub-scale correlate with a range of measures reflecting poor psychological adjustment. However, not all superstitious beliefs fall into this category. Some, such as carrying a charm to bring good luck, touching wood and crossing fingers, reflect a desire to bring about beneficial consequences by actively courting good luck or at least avoiding bad luck. Such positive superstitions may serve different psychological functions to negative superstitions. Indeed, as is the case with other forms of so-called ’positive illusions’ (Taylor, 1989), beliefs in these types of superstitions may actually be psychologically adaptive rather than maladaptive. A study found that the psychological correlates of superstitious belief vary depending on whether the belief is in positive or negative superstitions.

_

Origin of some of the superstition:

Breaking a Mirror:

Our ancestors began this superstition, because they thought the image in a mirror, contained our actual soul. Thus, a broken mirror represented the soul being pulled from your body and being trapped in all the shattered pieces. The reason the bad luck lasted for seven years, was because the Romans believed that after seven years, the body was physically renewed and the soul could once again return whole.

_

The Number Thirteen:

There are many different theories about the origin of 13 being considered an unlucky number. The earliest come from ancient religious beliefs. At Valhalla, the home of the Gods, if you had twelve guests at a feast, and a thirteenth turned up uninvited; he was thought to be “The God of Deceit”. Many Christians believed it started with witches’ covens having 12 members, making 13 only when the devil appeared at satanic ceremonies (although, prior to Christianity, 13 was considered a sacred number, representing the 13 moons of the year). For Christians, 13 was also the number at the Last Supper, when Judas betrayed Jesus.

_

Friday the 13th:

Friday the 13th is a date considered to be bad luck in western superstition. One theory states that it is a modern amalgamation of two older superstitions: that thirteen is an unlucky number and that Friday is an unlucky day. Friday has been an inauspicious day for a very long time, and in many varied cultures. It has been held to be both unlucky and as a day when evil influences are at work. It is claimed that Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden on a Friday. Noah’s flood started on a Friday and Christ was crucified on a Friday. There is the belief that stems from the order given by King Philip IV, on Friday, October 13, 1307, to round up the Knights Templar and kill or torture them.

_

Walking Under a Ladder:

If you walk under a ladder you supposedly break a spiritual triangle (the Holy Trinity) that will leave you vulnerable to the devil. In the days before the gallows, criminals were hung from the top rung of a ladder and their spirits were believed to linger underneath. Thus, to walk beneath an open ladder, was to pass through the triangle of evil ghosts and spirits.

_

Spilling Salt:

At one time salt was a rare commodity and thought to have magical powers. It has long been useful as a preservative, in medicine, and is also used in magic, ritual, and superstition to purify, bless things, and drive away evil. It was unfortunate to spill salt and was said to predict future family troubles and death.

_

Black Cats:

Black cats have long been believed to be a supernatural omen, since the witch hunts of the Middle Ages, when cats were thought to be connected to evil. Since then, it is considered bad luck if a black cat crosses your path. Ironically, a black cat walking towards you is considered lucky, while one walking away is said to be stealing your luck.

_

Sneezing:

The saying of “God bless you” after someone sneezed arose out of the belief that in the instant after expelling air from the nose, the Devil would attempt to jump into the sneezer’s body. By quickly saying the blessing, a friend could help prevent a person from becoming possessed. Although not as widely known was the similar custom of one holding a hand over his/her mouth when yawning so that the Devil or any other evil spirit would be prevented from getting into the person’s body.

_

Rabbit’s Foot:

These lucky charms are thought to ward off bad luck and bring good luck. You must carry the rabbit’s foot on a chain around your neck, or in your left back pocket. The older it gets the more good luck it brings.

_

Opening an umbrella indoors:

It’s not very practical to open an umbrella indoors, and forcing the opened contraption out of any doorway can prove difficult. In ancient times, when umbrellas were used to guard from the sun, it was thought that opening one inside would anger the sun god. Take the safer, easier route and just open it outdoors.

_

Cross your fingers:

Crossing the pointer and middle fingers of one hand signifies a desire or hope for a certain outcome or can be used when someone tells a lie, somehow absolving the teller from the consequences. It is thought that crossing one’s fingers in the sign of the Christian faith can prevent evil spirits from destroying one’s choice of good fortune.

__

Even in the 21st century, number 13 is considered unlucky; here are a few examples how superstitious we still are:

* In Scotland there is no gate 13, instead there is a gate 12B.

* Some airline jets skip row 13, going straight from 12 to 14.

* Some tall buildings have resorted to skipping the 13th floor, either by numbering it 14 or 12a.

* Some streets do not have a house number 13.

* In some motor sports, as an example formula 1, there is no number 13 car.

* Microsoft plans to skip Office 13 for being “an unlucky number” going directly to Office 14.

*The creators of the online game “Kingdom of Loathing avoid the number 13 in all their programming.

___

Common superstitions:

*If you see a shooting star it will bring you good luck.

*An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

*To find a four-leaf clover is to find good luck.

*Our fate is written in the stars.

*To make a happy marriage, the bride must wear: something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.

*The wedding veil protects the bride from the evil eye.

*You must get out of bed on the same side you got in on or you will have bad luck.

*Don’t eat chicken on New Year’s Day or you will be scratching for money but if you eat pork you will be fattened with prosperity/money.

*People believe that when you visit someone you should leave through the same door you came in or otherwise it is bad luck.

*If you step on a crack you will break your mother’s back.

*If it rains on your wedding day you will be showered with good luck.

_

Common superstitions in India:

*The “Vaastu” as a guide for floor plans of a house is a superstitious system.

*Right eye twitching is good for men; left eye twitching is good for women.

*If there is itching on the right palm (left for female) you can get some money or favors.

*Never sweep the house during night time or Lakshmi (fortune) will not enter your house.

_

Auspicious wedding date:

A number of cultures, including the Chinese and Hindu cultures, favor particular auspicious dates for weddings. Auspicious days may also be chosen for the dates of betrothals. Dates for a particular couple’s wedding may often be determined with the help of a traditional fortune-teller.

_

Classification of superstitions:

As discussed earlier, superstitions can be classified as personal, cultural and religious. There are other classifications also.

_

Logical classification:

1. Causality or the Perceived Causality:

It’s human nature to look for patterns and explanations, even if they are known to be totally unrelated. Derren Brown, a famous magician in the UK, presented a TV episode that showed people trying to find patterns based on a completely random event: a goldfish swimming in a bowl. This is called ‘associative learning’ (learning from coincidence), a variation of the famous experiment by B.F. Skinner on superstition and random events (vide infra). Indeed, people often have cognitive bias; attributing unfavourable events to bad luck while favourable outcomes to their own abilities.

2. Cultural Norm:

It is widely known that cultural norms affect business and economic decisions. Sometimes people act as if they are superstitious because of their respect for the local culture, leading to a phenomenon called ‘dissonance reduction’. This partly explains why a non-Asian CEO of a company operating in China would hire a Feng Shui master to help design the company’s headquarters or find a lucky date for an Initial Public Offering. These kinds of seemingly “irrational” actions further legitimize Feng Shui and this makes more people adopt this practice. But not all superstitious beliefs are completely baseless. The use of Feng Shui can improve a residence’s comfort attributes, including orientation, air flow, and ambiance.

3. Safety Bet:

Blaise Pascal, the inventor of probability theory from his card game business, became a devoted Christian, after reasoning that accepting Christianity was a safety bet: “if you believe in God and He does not exist, when you die you have nothing to lose. However, if you do not believe in God and He does exist, then you will be damned.” Therefore, rationality requires you to maximize your expected utility and wager (i.e. betting) for God.

4. Vanity:

A rare and super-lucky object tends to command a high price. If the owner can readily show off this object, they can definitively express their economic and social status, as demonstrated by our illustrative case of license-plate auction in Hong Kong. This case is interesting because a license plate, unlike the car, does not offer any directly consumable services (e.g. comfort and travel). Hence, the high price paid for a license plate with a particular combination of numbers mirrors a market valuation driven by superstition and vanity. Also, people are willing to pay a lot to get some “lucky” sounding numbers for safe ride.

_

Harm-benefit classification:

A simple classification divides superstitions into four categories which are:

1. Superstitions that cause harm to people:

The most extreme example in India is the belief that tantrics can cure people of snakebite. If the snake was non poisonous or did not get an opportunity to inject its full dose of venom, naturally the tantric’s cure works. Otherwise, it fails without exception. These are superstitions that need to be fought first. Curiously, this belief is not as easy to fight as it would first seem. The success rate for tantrics, for all snakebite cases brought to them, is about the same as (and possibly more than), the success rate of doctors with poisonous snakes. There are reasons for this: The tantric assumes that all snakes are poisonous. He gains credit or discredit for all cases brought to him. Since non-poisonous snakebites generally outnumber the poisonous ones, the tantric has a more than fair chance of being successful. The doctor, on the other hand, sends the patient home without any fuss, if he finds that the bite was by a non poisonous snake. His successes and failures get counted only for poisonous snake bites, where his success rate is not very high. About ten thousand people die of snakebite in India every year. Many of them can be saved, if they go to a doctor quickly, instead of going to a tantric.

_

2. Superstitions that do no harm and but accrue no benefit either:

In the second category, fall many religious beliefs. I feel that such beliefs should not be aggressively shot down, as the result may be quite the opposite of what is desired. How does it matter if someone insists on sleeping in an East-West direction rather than the North-South direction, or shaves his head off when a parent dies? Resistance to superstitions in this category often leads to reactive claims and social strife.

_

3. Superstitions that benefit people:

The third category might seem like a paradox to most rationalists. In many places in India, there are sacred groves- virgin patches of tropical forest, where even the most powerful dare not pluck a leaf, for fear of retribution. The grove is supposed to belong to the guardian deity and it is sacrilege to even think of stealing from it. Today, many of these forests have been declared protected by the Forest Dept. But even today, protection primarily comes, not from Forest Dept personnel, but from the old beliefs. Also, superstitions boost confidence of many athletes & actors and thereby improve their performance (vide infra).

_

4. Superstitions that have roots in common sense, but may not be relevant in today’s world, because of changed circumstances:

In India, there is a widespread belief that it is inauspicious to travel on amaavasyaa or New Moon day. Before the advent of electricity, such a belief would be plain common sense. It would be problematic to be stuck at night on a lonely road, with no moonlight to light up the way. It is a natural extension of this idea into a belief, that no religious or social ceremony should be performed on the New Moon day. People would not want their friends and relations to do any traveling on New Moon day, to attend such a ceremony.

__

As discussed earlier, superstitions can be personal, cultural and religious. Personal superstitions are different from culturally transmitted superstitions. E.g. Number 7 is lucky in the UK, but number 9 is lucky in Thailand. Maybe people adopt cultural superstitions because they provide a sense of control. According to Whitson & Galinsky – people who are given a reduced sense of control are more likely to develop superstitions (vide infra).

_

Superstitions as customs:

Customs and Superstitions have been part of everyday life for hundreds of years. Every country has its’ own particular festivals and customs which set the pattern for the year. Many races hand down their history through stories, songs, legends, customs and superstitions. Custom often is another key part of the development of superstition. When one practices certain acts over and over, the constant repetition becomes an unconscious act. For example, avoiding walking under ladders, throwing salt over your left shoulder after spilling the shaker, or possibly you have some type of good luck charm that you just automatically place in your pocket before heading out your front door to begin your day. Many of us practice customary superstitions without even realizing it. That doesn’t make us gullible or ridiculous; it just makes us humans who are generally creatures of habit…or superstition. Culture and heritage as well as time continuity and change offer students the opportunity to explore both their past and the past of others to establish a link through time.

_

Right Hand:

Since early times children have been encouraged to write with their right hands, those who preferred their left hands were thought to be clumsy, awkward or even ‘ill-omened.’ The right hand was thought to be stronger than the left, the right foot the preferred foot to put on the floor, when getting out of the right side of bed in the morning; the right sock and right shoe to be put on first, the right foot being that which is the ‘best foot to put forward’. The right hand has always been used to place on the Bible to affirm an oath of allegiance.

_

Sneezing:

Sneezing used to be thought of as a time of great danger; in ancient times it was thought to indicate ill – omens, the presence of evil spirits, a soul leaving the body, or an indication of the plague. Saying ‘God bless you’ was a method of protection against evil forces. Many superstitions surround sneezing, it is thought that three sneezes in a row predict good luck; the number three has been associated with good fortune for many centuries.

_

Yawning:

Yawning, without covering the mouth, has been thought to be rude since primitive times. Before advent of modern methods of oral hygiene, covering the mouth whilst yawning was a method of disguising bad breath. Man’s spirit was identified with his breath, the mouth being the point of entry and exit, to cover the mouth was the method by which the spirit was prevented from leaving the body. Leaving the mouth open was thought to be an invitation to evil spirits. Hindu people used to snap their fingers in front of their open mouths to chase away the ‘evil one’. In some European countries the sign of the cross is made in front of the face for the same reason.

_

Superstitions as habits:

Legendary Dutch footballer Johan Cruyff used to slap his goalkeeper in the stomach before each match. Tennis ace Serena Williams always bounces her ball five times before her first serve. Jennifer Aniston, it is reported, touches the outside of any plane she flies in with her right foot before boarding. From touching wood for good luck, to walking around ladders to avoid bad luck, we all have little routines or superstitions, which make little sense when you stop to think about them. And they are not always done to bring us luck. We wait until just after the kettle has boiled to pour the water for a cup of tea, rather than pouring just before it boils. I do not know why we feel the need to do this, I am sure it cannot make a difference to the drink. So, why do we repeat such curious habits? Behind the seemingly irrational acts of kettle boiling, ball bouncing or stomach slapping lies something that tells us about what makes animals succeed in their continuing evolutionary struggles (vide infra).

_

Ritual and superstition:

The definition of “ritual” as it applies to habitual behavior is a pattern of behavior that regularly occurs in a defined manner. The definition of “superstition” as it applies to habitual behavior is an act based on a belief not based on knowledge or reason. So, although superstitious behavior can be ritualistic, not all ritualistic behavior is superstitious. After all, not all rituals or beliefs are superstitions. The dividing line is whether you give some kind of magical significance to the ritual. A ritual for a tennis player could be focusing on the racket strings between points; a superstition for a tennis player could be always entering a tennis court from the north side. In other words, a ritual can help an athlete to stay centered, whereas a superstition can unnerve an athlete when the athlete cannot perform the habitual behavior associated with the superstition. These rituals provide a level of comfort and a way for someone to control a situation. One of the things the great athletes do, is they try to keep their environment consistent. One of the philosophy of sports is that your environment either enables you to win, or enables you to lose. I views rituals as a way to block out “psychological noise” in the environment. Rituals may even be a distraction paradox. Katz said that by distracting themselves with straws, with fingernail clippings, or something else, athletes are actually finding ways to tune out the larger distractions that may come with the game.

_

There is a clear psychological value to establishing a routine — coaches often tell players that if they don’t have a pre-game ritual they should try to establish one simply because it focuses your mind in a mantra-like way to keep the anxiety away. That’s quite rational. It becomes a superstition when it moves over to magical thinking. So when you step on the line three times before you go out onto the field, it is ritual but when you think that it is must for winning a game, then it has gone beyond the ritual aspect of it and has moved on to some incantation — a magical feature. The difference between a ritual and a superstition is in the expected outcome. If you believe that performing your morning ritual or your pre-game routine can alter the outcome, then it’s a superstition. If you just do it to calm yourself before taking a plunge into an important event, the ritual continues as a ritual. The interesting thing is that while routines have a psychological benefit, so do superstitions.

_

You might be wondering if certain superstitious behaviors — such as like counting the number of times you tap a ball — are really a sign of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). People with OCD often have compulsions to do rituals over and over again, often interfering with everyday life. A good example is Jack Nicholson’s character in the movie As Good As It Gets, who skips cracks in the sidewalk and eats at the same table in the same restaurant every day, with an inability to cope with any change in routine. While some of the symptoms of OCD can mimic superstitious behavior (and the two aren’t mutually exclusive), most of the evidence would indicate there is no connection between the two. Psychiatrists don’t think of anxiety disorders [such as OCD] as superstitious thinking. They think of it as irrational thinking, and most of their patients understand that.

_

Athletes of all sorts practice pre-game rituals religiously. These rituals supply the confidence they need to ensure they will be able to play, run, or throw how they wants. Self-confidence is holding the belief that you have the ability to execute the necessary skills and have the physical fitness to come out of a performance successfully. This is essential to an athlete’s success. How a player feels can make all the difference; even more than an athlete’s ability. This is why pre-game rituals and “superstitions” really are not bogus in sports. In fact, they sometimes have the power to improve or hurt an individual’s or a team’s performance (vide infra). Competitions and big performances of any kind (from musical shows to chess tournaments to basketball games) can cause the participant a lot of stress. The pressure to do well can cause an individual’s heart rate to increase, muscles to tense up, cold sweats to break out, and concentration to decrease. A competitor does need a certain amount of physical and emotional stimulation in advance, but too much can lead to anxiety. Rituals are a way of tweaking our bodies, moving our physical and psychological apparatus to the level that we know is the best level for our performance. Ritual helps you get to that best point.

_

Superstitions vis-à-vis supernatural through rational thinking:

Supernatural is a force which is a part of the outside world. Some people believe in spirits, demons, omens and goblins. They believe in miracles, curses, and many other things which have no meaning or existence. Superstition and belief in the supernatural seem to go hand in hand. Indeed, there appears to be (at the very least) a mutually supportive relationship between the two. On the one hand, supernatural beliefs create a context in which particular superstitious practices may be thought to be effective or necessary. Thus, if one believes in evil spirits, the way is open to thinking that there are ways of protecting against them or getting them to do ones biding. To put it another way, supernatural beliefs will include or entail beliefs about supernatural causal connections that may be used to one’s possible advantage. On the other hand, the seeming effectiveness of superstitious practices requires supernatural explanations, such as are offered by supernatural beliefs. This can be seen in the case of lucky talismans: it would be difficult to give a naturalist explanation for why rabbit feet ‘bring’ luck given that luck is not a category that exists outside the context of our needs or wants. Given the apparent connection between supernatural and superstitious beliefs, it becomes interesting to consider whether we can even talk about superstitious beliefs that do not at least entail supernatural ones. Consider the belief that there is a causal connection between wearing a particular shirt and doing well on mathematics exams. This belief is open to either a natural or a supernatural explanation. A natural explanation might be that the person in question feels more comfortable while wearing it or, to chose a less positive possibility, that they have crib-sheets inside the sleeves. The supernatural explanation might be that the shirt once belonged to a great mathematician and still carries something of that genius with it. Only in the case that the explanation given is a supernatural one can we talk about a superstitious belief. Similarly for practices, it only seems appropriate to call them superstitious if the people engaging in them give supernatural explanations for their meaning. The cases where no explanation is given seem to be indeterminate.

_

Superstition vis-à-vis supernatural through religion:

Superstition is any sort of belief or behavior which is magical. A magical understanding of the religion is primitive, immature and dangerous. Basically a superstitious or magical understanding of religion involves sympathetic magic or an irrational link between certain behaviors and their outcomes. It means, in some way, we are trying to manipulate things to produce an outcome that we desire. Sympathetic magic links two otherwise unconnected things together–usually one physical and the other metaphysical and expects a causal result. So, for example, you have a black cat, and you believe that black cat symbolizes evil, so you cast a spell which you believe transfers the evil to the black cat, then you kill the black cat in order kill the evil. The form of magic which makes an irrational link between certain behaviors or objects with their outcomes is just as dangerous. So a person may believe that by walking in a circle clockwise thirteen times and throwing salt over the shoulder will ward off the evil eye. Similarly, carrying a rabbit’s foot or some other talisman to bring good luck or blessing or to ward off evil is a form of magic that makes an irrational link between an object or behavior and the desired result. It is easy to think that the opposite of being superstitious is to be materialistic and dismissive of all everything supernatural. Untrue. The true balance to superstition is not materialism, but supernaturalism. The truly supernatural view is based on the foundational belief that the grace of God is working in our world and through our lives. It allows for, and expects miracles. The other distinction between the superstitious and the supernatural is the direction of the interaction. With superstition, or what might be called magic, the practitioner is always manipulating the material world in order to manipulate the supernatural world for his own benefit. We kill a black cat to kill the evil powers that threaten us. We wear a talisman to ward off the evil eye. We say prayers and do penance to get God to give us what we want. We wear a scapular to escape hell. We fast in order to get what we want. In other words, the whole transaction is initiated by us to get what we want. By extension, therefore, much of our activity in the world of living to make money, gain power and prestige and protection through the acquisition of more and more money–is a sort of witchcraft. Supernaturalism, on the other hand, is God’s grace coming to us through the natural world. In superstition we try to impose our will. In Supernaturalism we try to conform to God’s will. In superstition we do something to get our way. In supernaturalism God does something to change us to his way. This is why when we do bring our prayer requests to God we always include the prayers, “According to your will.”

__

Superstitions and religion:

_

_