Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

SCIENCE OF LANGUAGE

_

SCIENCE OF LANGUAGE:

_

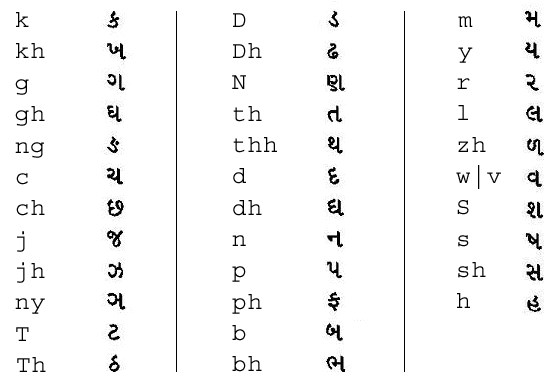

The figure above shows English to Gujarati mappings for consonants:

_________

Prologue:

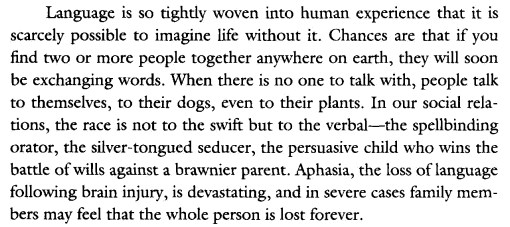

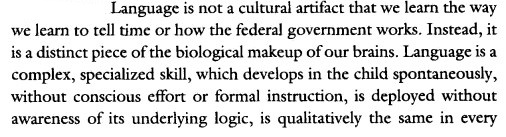

Human life in its present form would be impossible and inconceivable without the use of language. To the question: “Who is speaking?” Mallarme, the French poet, answered, “Language is speaking.” The traditional conception of language is that it is, in Aristotle’s phrase, sound with meaning. Everybody uses language, but nobody knows quite how to define it. Language is arguably the defining characteristic of the human species, yet the biological basis of our ability to speak, listen and comprehend remains largely mysterious; about its evolution, we know even less. The origin of language is a widely-discussed topic. Whole doctorates have been based on it, thousands of books have been written on it, and scholars continue to argue about how and why it first emerged. Many animals can communicate effectively with one another but humans are unique in our ability to acquire language. Scientists have long questioned how we are able to do this. Language, more than anything else, is what makes us human; the unique power of language to represent and share unbounded thoughts is critical to all human societies, and has played a central role in the rise of our species in the last million years from a minor and peripheral member of the sub-Saharan African ecological community to the dominant species on the planet today. Language is an integral part of humans. It surpasses communication and social interaction. Language influences thought, and thought often conditions action, and also influences conduct. Language therefore is the strongest medium of transmitting culture and social reality. Human civilization has been possible only through language. It is through language only that humanity has come out of the Stone Age and has developed science, art and technology in a big way. No two individuals use a language in exactly the same way. The vocabulary and phrases people use are linked to where they live, their age, education level, social status and sometimes to their membership in a particular group or community. Is capacity to acquire language innate or learned? Do different languages mean different ways of thinking? Are languages and thought separate? Should Aristotle’s maxim be inverted i.e. language is meaning with sound. I attempt to answer these questions. My biological parents were English speaking and they were worried whether I would ever speak English as I was brought up in third world country whose native language was not English. Today, as a privileged son of English speaking parents, I attempt to solve the greatest mystery of all time, language.

________

Inspirational Quotes for Language Learners:

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.”

‒Nelson Mandela

“To have another language is to possess a second soul.”

‒Charlemagne

“Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.”

‒Rita Mae Brown

__________

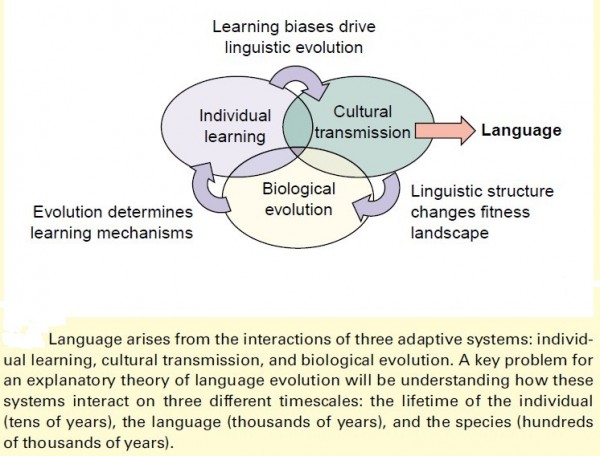

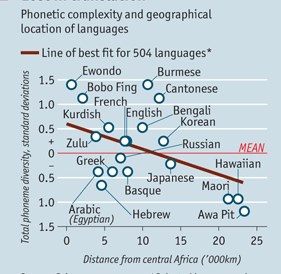

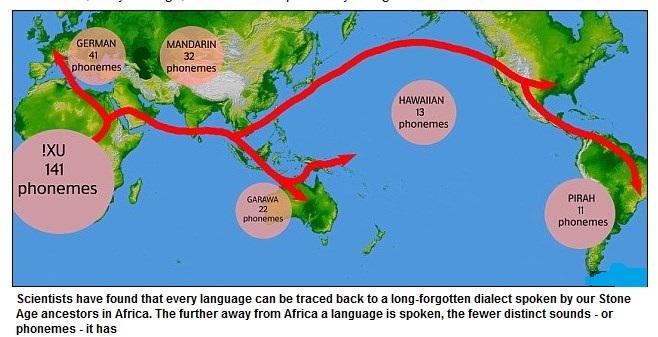

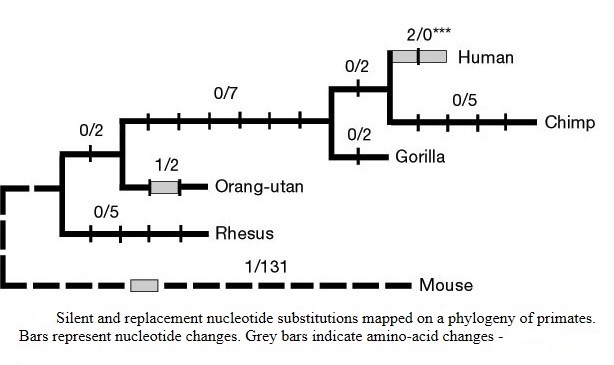

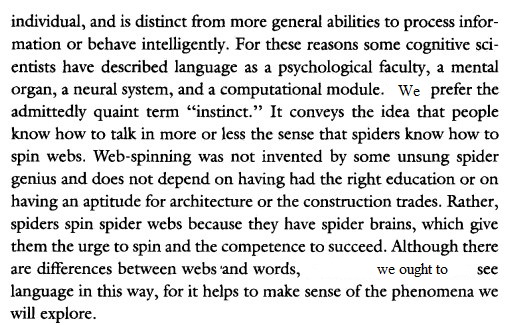

Because of its central role in human culture and cognition, language has long been a core concern in discussions about human evolution. Languages are learned and culturally transmitted over generations, and vary considerably between human cultures. But any normal child from any part of the world can, if exposed early enough, easily learn any language, suggesting a universal genetic basis for language acquisition. In contrast, chimpanzees, our nearest living relatives, are unable to acquire language in anything like its human form. This indicates some key components of the genetic basis for this human ability evolved in the last 5–6 million years of human evolution, but went to fixation before the diaspora of humans out of Africa roughly 50,000 years ago. Darwin recognized a dual basis for language in biology and culture: ‘language is … not a true instinct, for every language has to be learnt. It differs, however, widely from all ordinary arts, for man has an instinctive tendency to speak, as we see in the babble of our young children; while no child has an instinctive tendency to brew, bake or write’.

_

That which distinguishes man from the lower animals is not the understanding of articulate sounds, for, as everyone knows, dogs understand many words and sentences . . . It is not the mere articulation which is our distinguishing character, for parrots and other birds possess this power. Nor is it the mere capacity of connecting definite sounds with definite ideas; for it is certain that some parrots, which have been taught to speak, connect unerringly words with things, and persons with events. The lower animals differ from man solely in his almost infinitely larger power of associating together the most diversified sounds and ideas; and this obviously depends on the high development of his mental powers.

Charles Darwin, 1871, The Descent of Man

_

_

___________

Introduction to language and speech:

_

Let me begin article by differentiating between language and speech:

In order to understand the importance of language, we have to know the difference between two commonly confused terms — speech and language. Some dictionaries and textbooks use the terms almost interchangeably. But for scientists and medical professionals, it is important to distinguish among them. Speech and language are often confused, but there is a distinction between the two:

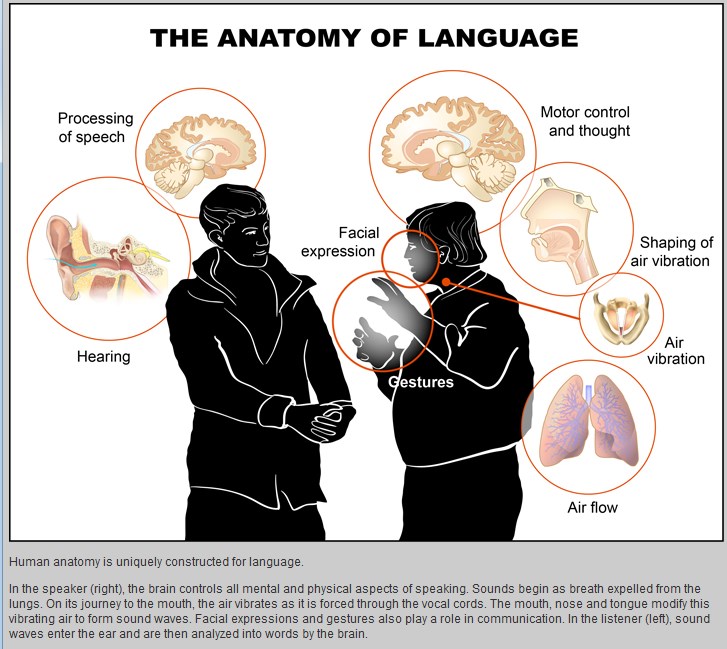

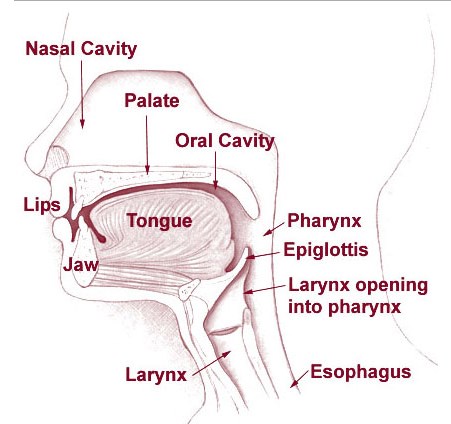

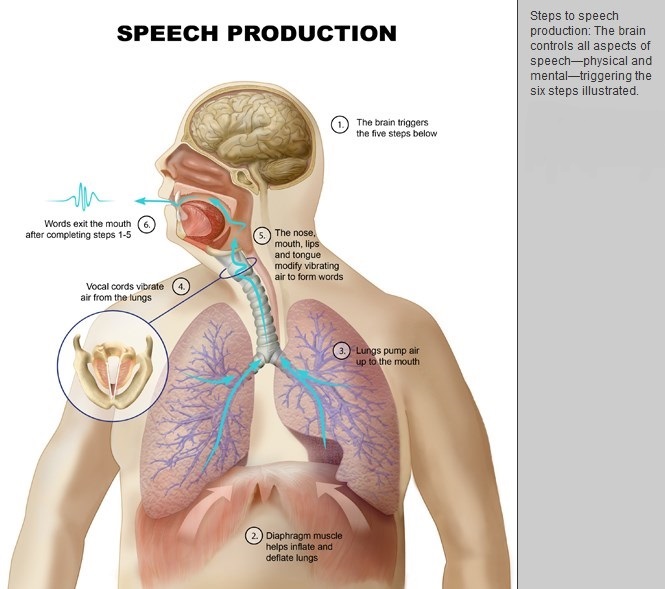

1. Speech is the verbal expression of language and includes articulation, which is the way sounds and words are formed. Humans express thoughts, feelings, and ideas orally to one another through a series of complex movements that alter and mold the basic tone created by voice into specific, decodable sounds. Speech is produced by precisely coordinated muscle actions in the head, neck, chest, and abdomen. Speech means producing the sounds that form words. It’s a physical activity that is controlled by the brain. Speech requires coordinated, precise movement from the tongue, lips, jaw, palate, lungs and voice box. Making these precise movements takes a lot of practice, and that’s what children do in the first 12 months. Children learn to correctly articulate speech sounds as they develop, with some sounds taking more time than others.

2. Language is much broader and refers to the entire system of expressing and receiving information in a way that’s meaningful. It is understanding and being understood through communication — verbal, nonverbal, and written. Language is the expression of human communication through which knowledge, belief, and behavior can be experienced, explained, and shared. This sharing is based on systematic, conventionally used signs, sounds, gestures, or marks that convey understood meanings within a group or community.

_

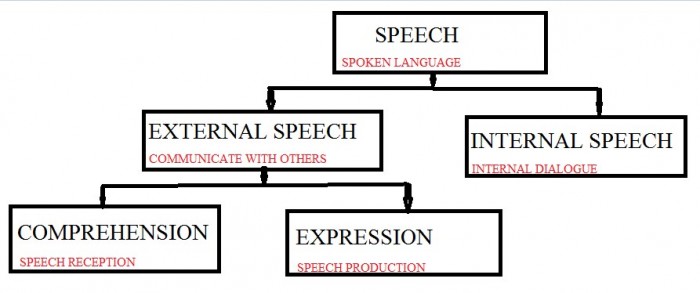

Speech:

Speech is the verbal means of communicating. It’s how spoken language is conveyed. Speech includes the following:

1. Voice:

Voice (or vocalization) is the sound produced by humans and other vertebrates using the lungs and the vocal folds in the larynx, or voice box. Voice is not always produced as speech, however. Infants babble and coo; animals bark, moo, whinny, growl, and meow; and adult humans laugh, sing, and cry. Voice is generated by airflow from the lungs as the vocal folds are brought close together. When air is pushed past the vocal folds with sufficient pressure, the vocal folds vibrate. If the vocal folds in the larynx did not vibrate normally, speech could only be produced as a whisper. The voice is characterized by pitch, loudness, and resonance (oral- or nasal-). Pitch is the highness or lowness of a sound based on the frequency of the sound waves. Loudness is the perceived volume (or amplitude) of the sound, while quality refers to the character or distinctive attributes of a sound. Many people who have normal speaking skills have great difficulty communicating when their vocal apparatus fails. This can occur if the nerves controlling the larynx are impaired because of an accident, a surgical procedure, a viral infection, or cancer. Your voice is as unique as your fingerprint. It helps define your personality, mood, and health.

2. Articulation:

Articulation means how speech sounds are produced by the articulators (lips, teeth, tongue, palate, and velum). For example, a child must be able to produce an /m/ sound to say “me.”

3. Fluency:

Fluency means how smoothly the sounds, syllables, words, and phrases are joined together in spoken language.

_

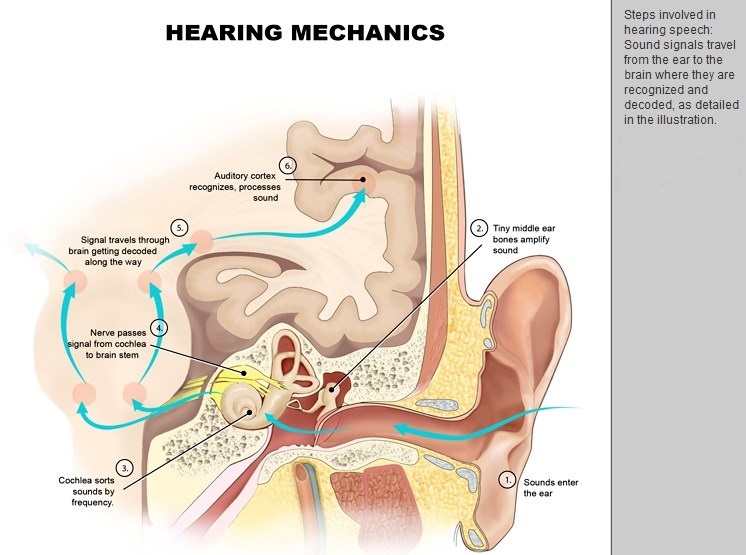

Speech sounds are propagated in air just like any other sound waves to be received by ears which convert speech sound waves into electrical impulse to be interpreted by brain to ascribe meaning to these sounds.

_

Language:

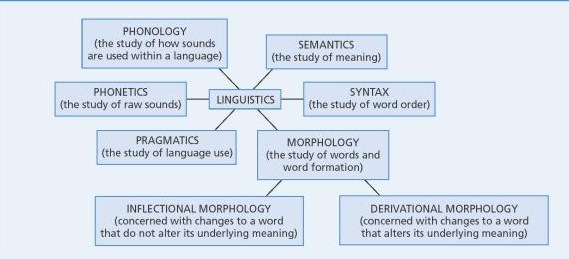

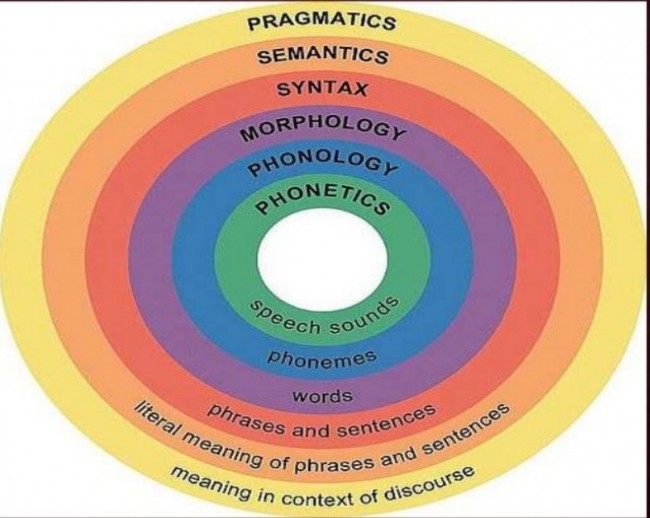

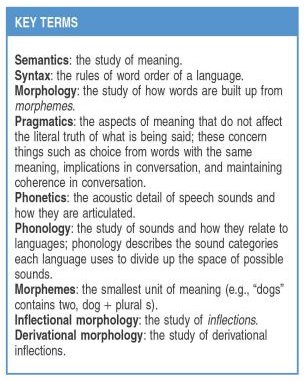

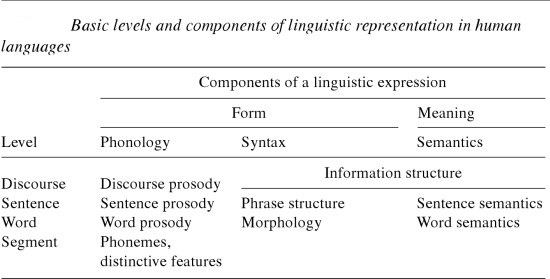

Language is a system of socially shared rules that are understood (i.e. Language Comprehension or Receptive Language) and expressed (i.e. Expressive Language and Written Language) that includes the following:

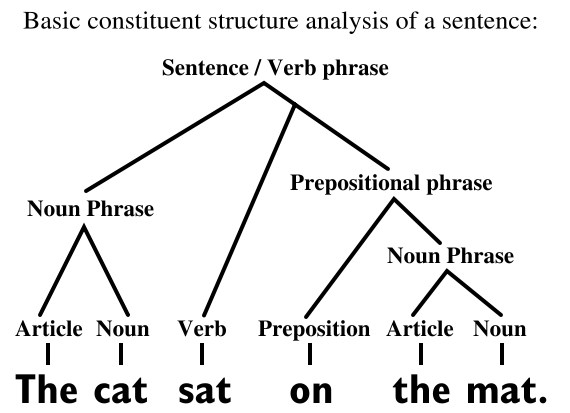

a) Form: how words are put together that make sense (syntax or grammar); also how new words are formed (morphology). Grammar or syntax rules are learned through the experience of language.

b) Content: what words mean (semantics)

c) Use: how the language is used to convey meaning in specific contexts (pragmatics)

d) Vocabulary is the store of words a person has – like a dictionary held in long-term memory.

e) Discourse is a language skill that we use to structure sentences into conversations, tell stories, poems and jokes, and for writing recipes or letters. It’s amazing to think that very young children begin to master such a complex collection of concepts.

_

In a nutshell, the term language includes speech but speech only means verbal (spoken) expression of language. Speech is an important element of language but not synonymous with language. On a much deeper level, speech is use of sound waves to transmit and receive language while non-speech language needs light for receiving language through eyes (reading) and uses hand movement for transmitting language in the form of writing or gestures. The term language encompasses not only transmitting and/or receiving language using sound, light and hand movements but also ascribing meaning to it and also converting thoughts into expression.

_________

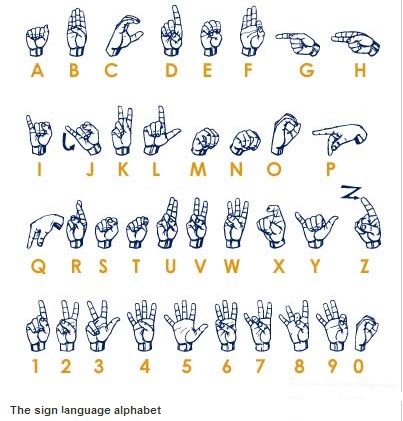

Remember; sound, light and hand movements are vehicles of language. They carry language. They are not language. Their interpretation by brain is language. Sigh language is used by deaf people. Again, it is hand movements which carry language though light into eyes of deaf person. If you start writing with your finger on skin of deaf person (post-lingual deaf), he will still understand it as now language is carried by skin touch receptors but he has to see you writing on his skin as touch receptors on skin alone cannot transmit language but touch plus vision can give better transmission of language. This is my novel way of communication to deaf person if you are sitting next to him. Instead of using sign language, you write on his body skin and it will transmit language to him. Elderly populations have common hearing problem. This novel technique of skin reading will help communication with such population. No pen no paper, just fingers. You can also write on paper and ask elderly to read but it needs paper and pen while skin reading will need nothing. Also, elderly will not need to learn sign language. Remember, Braille Code used by blind people use skin touch receptors to read language but it has to be learned. Skin reading will not need any learning as written language is already learned in childhood. Skin reading is better than lip reading by deaf people as many phonemes share the same viseme and thus are impossible to distinguish from visual information alone, sounds whose place of articulation is deep inside the mouth or throat are not detectable , and lip reading takes a lot of focus, and can be extremely tiring (vide infra).

______

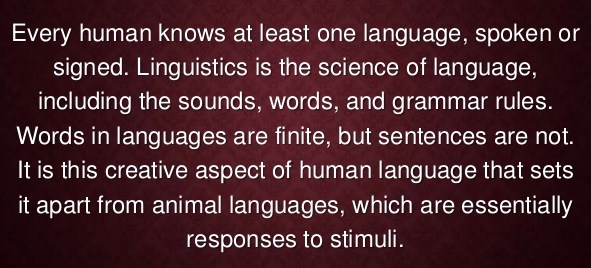

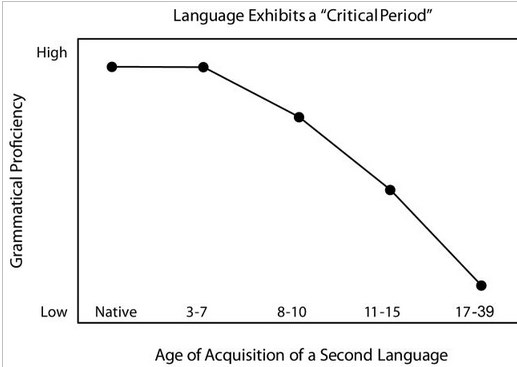

All languages begin as speech, and many go on to develop writing systems. Natural languages are spoken or signed, but any language can be encoded into secondary media using auditory, visual, or tactile stimuli – for example, in graphic writing, braille, or whistling. This is because human language is modality-independent. When used as a general concept, “language” may refer to the cognitive ability to learn and use systems of complex communication, or to describe the set of rules that makes up these systems, or the set of utterances that can be produced from those rules. All languages rely on the process of semiosis to relate signs with particular meanings. All can employ different sentence structures to convey mood. They use their resources differently for this but seem to be equally flexible structurally. The principal resources are word order, word form, syntactic structure, and, in speech, intonation. Relationships between languages are traced by comparing grammar and syntax and especially by looking for cognates (related words) in different languages. Language has a complex structure that can be analyzed and systematically presented (linguistics). Human language has the properties of productivity, recursivity, and displacement, and relies entirely on social convention and learning. Its complex structure affords a much wider range of expressions than any known system of animal communication. Different languages keep indicators of number, person, gender, tense, mood, and other categories separate from the root word or attach them to it. The innate human capacity to learn language fades with age, and languages learned after about age 10 are usually not spoken as well as those learned earlier.

_

Speaking is in essence the by-product of a necessary bodily process, the expulsion from the lungs of air charged with carbon dioxide after it has fulfilled its function in respiration. Most of the time one breathes out silently, but it is possible, by adopting various movements of lip, tongue, palate and by making vibrations in vocal cords; we interfere with the egressive airstream so as to generate noises of different sorts. This is what speech is made of.

_

Every physiologically and mentally normal person acquires in childhood the ability to make use, as both speaker and hearer, of a system of vocal communication that comprises a circumscribed set of noises resulting from movements of certain organs within the throat and mouth. By means of these noises, people are able to impart information, to express feelings and emotions, to influence the activities of others, and to comport themselves with varying degrees of friendliness or hostility toward persons who make use of substantially the same set of noises.

_

Different systems of vocal communication constitute different languages; the degree of difference needed to establish a different language cannot be stated exactly. No two people speak exactly alike; hence, one is able to recognize the voices of friends over the telephone and to keep distinct a number of unseen speakers in a radio broadcast. Yet, clearly, no one would say that they speak different languages. Generally, systems of vocal communication are recognized as different languages if they cannot be understood without specific learning by both parties, though the precise limits of mutual intelligibility are hard to draw and belong on a scale rather than on either side of a definite dividing line. Substantially different systems of communication that may impede but do not prevent mutual comprehension are called dialects of a language. In order to describe in detail the actual different speech patterns of individuals, the term idiolect, meaning the speech habits of a single person, has been coined.

_

Is language human invention:

_

Normally, people acquire a single language initially—their first language, or mother tongue, the language spoken by their parents or by those with whom they are brought up from infancy. Subsequent “second” languages are learned to different degrees of competence under various conditions. These terms first & second language are figurative in that the knowledge of particular languages is not inherited but learned behavior. Nonetheless, since the mid-20th century, linguists have shown increasing interest in the theory that, while no one is born with a predisposition toward any particular language, all human beings are genetically endowed with the ability to learn and use language in general. Complete mastery of two languages is designated as bilingualism; in many cases—such as upbringing by parents speaking different languages at home or being raised within a multilingual community—speakers grow up as bilinguals. In traditionally monolingual cultures, such as those of Britain and the United States, the learning, to any extent, of a second or other language is an activity superimposed on the prior mastery of one’s first language and is a different process intellectually.

_

Remember:

L 1 means first language or mother tongue.

L 2 means second language.

_

One of the dictionary meanings of language is the communication of feelings and thoughts through a system of particular signals, like sounds, voice, written symbols, and gestures. It is considered to be a very specialized capacity of humans where they use complex systems for communication. There are many languages spoken today by humans. Languages have some rules, and they are compiled and used according to those rules for communication. Languages can be not only written, but sometimes some languages are based on signs only. These are called sign languages. In other cases, some particular codes are used for computers, etc. which are called computer languages or programming. Language can be either receptive, meaning understanding of a language, and expressive language, which means the usage of the language either orally or in writing. If we simplify everything, language expresses an idea communicated in the message.

_

Language, as described above, is species-specific to human beings. Other members of the animal kingdom have the ability to communicate, through vocal noises or by other means, but the most important single feature characterizing human language (that is, every individual language), against every known mode of animal communication, is its infinite productivity and creativity. Human beings are unrestricted in what they can talk about; no area of experience is accepted as necessarily incommunicable, though it may be necessary to adapt one’s language in order to cope with new discoveries or new modes of thought.

_

Language interacts with every aspect of human life in society, and it can be understood only if it is considered in relation to society. Because each language is both a working system of communication in the period and in the community wherein it is used and also the product of its history and the source of its future development, any account of language must consider it from both these points of view. Language is also a way of establishing rules, to bring some order in the reality. People try to make sense of the chaos by attributing meaning through symbolization.

_

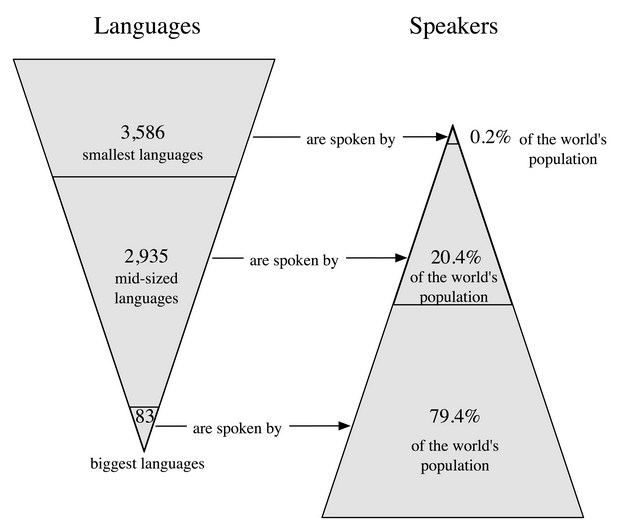

In most accounts, the primary purpose of language is to facilitate communication, in the sense of transmission of information from one person to another. However, sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic studies have drawn attention to a range of other functions for language. Among these is the use of language to express a national or local identity (a common source of conflict in situations of multiethnicity around the world, such as in Belgium, India, and Quebec). Also important are the “ludic” (playful) function of language—encountered in such phenomena as puns, riddles, and crossword puzzles—and the range of functions seen in imaginative or symbolic contexts, such as poetry, drama, and religious expression. Language plays a vital role in relation to identity, communication, social integration, education and development. There is a human right for people to speak their mother tongue and somewhere over 6,000 languages are spoken today. However, it is estimated that without measures in place to protect and promote minority and endangered languages, half of them will disappear by the end of the present century. 96 of these languages are spoken by a mere 4% of the world’s population and according to UNESCO, 29% of the world’s languages are in danger and a further 10% are considered to be vulnerable. UNESCO promotes education that is based on a bilingual or multi-lingual approach with an emphasis on the use of the mother tongue. Research has shown that this has a positive impact on learning and its outcomes.

_

Language is an extremely important way of interacting with the people around us. We use language to let others know how we feel, what we need, and to ask questions. We can modify our language to each situation. For instance, we talk to our small children with different words and tone than we conduct a business meeting. To communicate effectively, we send a message with words, gestures, or actions, which somebody else receives. Communication is therefore a two-way street, with the recipient of the message playing as important a role as the sender. Therefore, both speaking and listening are important for communication to take place. Through language we can connect with other people and make sense of our experiences.

_

What you know about language:

_

Internal speech:

Well, probably 99.9 percent of language’s use is internal to the mind. You can’t go a minute without talking to yourself. It takes an incredible act of will not to talk to yourself. We don’t often talk to ourselves in sentences. There’s obviously language going on in our heads, but in patches, in parallel, in fragmentary pieces, and so on.

____________

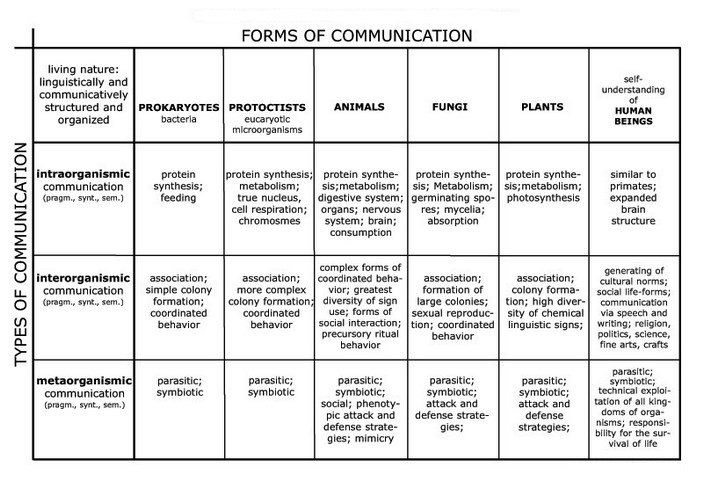

Communication: animal and human:

Communication is the activity of conveying information through the exchange of thoughts, messages, or information, as by speech, visuals, signals, written, or behavior. It is the meaningful exchange of information between two or more living creatures. One definition of communication is “any act by which one person gives to or receives from another person information about that person’s needs, desires, perceptions, knowledge, or affective states. Communication may be intentional or unintentional, may involve conventional or unconventional signals, may take linguistic or non-linguistic forms, and may occur through spoken or other modes.”

_

_

By age four, most humans have developed an ability to communicate through oral language. By age six or seven, most humans can comprehend, as well as express, written thoughts. These unique abilities of communicating through a native language clearly separate humans from all animals. The obvious question then arises, where did we obtain this distinctive trait? Organic evolution has proven unable to elucidate the origin of language and communication. Knowing how beneficial this ability is to humans, one would wonder why this skill has not evolved in other species. Linguistic research, combined with neurological studies, has determined that human speech is highly dependent on a neuronal network located in specific sites within the brain. This intricate arrangement of neurons, and the anatomical components necessary for speech, cannot be reduced in such a way that one could produce a “transitional” form of communication. The fact of the matter is that language is quintessentially a human trait. All attempts to shed light on the evolution of human language have failed—due to the lack of knowledge regarding the origin of any language, and due to the lack of an animal that possesses any ‘transitional’ form of communication. This leaves evolutionists with a huge gulf to bridge between humans with their innate communication abilities, and the grunts, barks, or chatterings of animals. By the age of six, the average child has learned to use and understand about 13,000 words; by eighteen it will have a working vocabulary of 60,000 words. That means it has been learning an average of ten new words a day since its first birthday, the equivalent of a new word every 90 minutes of its waking life. Even under these loosened criteria, there are no simple languages used among other species, though there are many other equally or more complicated modes of communication. Why not? And the problem is even more counterintuitive when we consider the almost insurmountable difficulties of teaching language to other species. This is surprising, because there are many clever species. Though researchers report that language-like communication has been taught to nonhuman species, even the best results are not above legitimate challenges, and the fact that it is difficult to prove whether or not some of these efforts have succeeded attests to the rather limited scope of the resulting behaviors, as well as to deep disagreements about what exactly constitutes language-like behavior.’

_

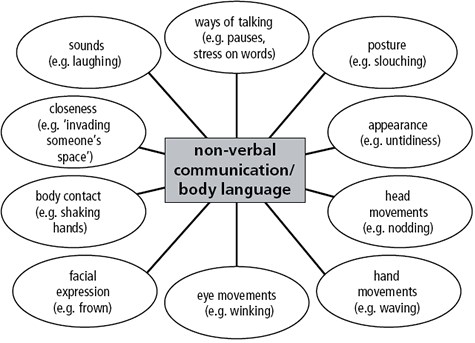

Body language:

There are a variety of verbal and non-verbal forms of communication. These include body language, eye contact, sign language, haptic communication, and chronemics. Other examples are media content such as pictures, graphics, sound, and writing. Body language refers to various forms of nonverbal communication, wherein a person may reveal clues as to some unspoken intention or feeling through their physical behaviour. These behaviours can include body posture, gestures, facial expressions, and eye movements. Body language also varies depending on the culture and most behaviors are not universally accepted. Besides humans, animals also use body language as a communication mechanism. Body language is typically subconscious behaviour, and is therefore considered distinct from sign language, which is a fully conscious and intentional act of communication. Body language may provide clues as to the attitude or state of mind of a person. For example, it may indicate aggression, attentiveness, boredom, a relaxed state, pleasure, amusement, and intoxication. Body language is significant to communication and relationships. It is relevant to management and leadership in business and also in places where it can be observed by many people. It can also be relevant to some outside of the workplace. It is commonly helpful in dating, mating, in family settings, and parenting. Although body language is non-verbal or non-spoken, it can reveal much about your feelings and meaning to others and how others reveal their feelings toward you. Body language signals happen on both a conscious and unconscious level.

_

_

Are Non-verbal skills more important than the Verbal ones?

One statistics from a UCLA study suggested that as much as 93% of communication may be from aspects unconnected to the words we use. . It’s one of the longest standing study results that has become a synonym for how language works. Only in recent years have people explored again what the contents of that study were. The study which dates back to 1967 had a very different purpose and wasn’t at all about defining how we process language. “The fact is Professor Mehrabian’s research had nothing to do with giving speeches, because it was based on the information that could be conveyed in a single word.” Here is what actually happened that triggered the above result. “Subjects were asked to listen to a recording of a woman’s voice saying the word “maybe” three different ways to convey liking, neutrality, and disliking. They were also shown photos of the woman’s face conveying the same three emotions. They were then asked to guess the emotions heard in the recorded voice, seen in the photos, and both together. The result? The subjects correctly identified the emotions 50 percent more often from the photos than from the voice.” The truth, so famous author Philip Yaffe argues is that the actual words “must dominate by a wide margin”. One anecdotal study cannot make non-verbal communication dominate over verbal communication.

_

Communication versus Language:

Humans have the ability to encode and develop abstract ideas and engage in problem solving. It is this ability that allows man to use language in its simplest and complex forms. Animal communication lacks the complexity we associate with human language based on the nature and functions of language. While animals may possess some of these features, humans by far possess all. Communication is not synonymous with language. It is true that all language facilitates communication; however, not all communication is considered language. Animals communicate using instinct most times. However, to say animals use language must be proven based on the functions of language as well as the nature of language. Human communication was revolutionized with speech approximately 100,000 years ago. Symbols were developed about 30,000 years ago, and writing about 5000 years ago.

_

Animal communication and language:

1. How do the forms of communication used by animals differ from human language?

2. Can animals be taught to use languages that are analogous to or the same as human language?

Pearce (1987, p252) cites a definition of animal communication by Slater:

Animal communication is “the transmission of a signal from one animal to another such that the sender benefits, on average, from the response of the recipient. This loose definition permits the inclusion of many types of behaviour and allows “communication” to be applied to a very large range of animals, including some very simple animals. Natural animal communication can include:-

•Chemical signals (used by some very simple creatures, including protozoa)

•Smell (related to chemical signals, e.g. pheromones attract, skunk secretions repel)

•Touch

•Movement

•Posture (e.g. dogs, geese)

•Facial gestures (e.g. dogs snarling)

•Visual signals (e.g. feathers)

•Sound (e.g. very many vertebrate and invertebrate calls)

Such signals have evolved to:-

•attract (especially mates)

•repel (especially competitors or enemies)

•signal aggression or submission

•advertise species

•warn of predators

•communicate about the environment or the availability of food

Such signals may be:-

•instinctive, that is genetically programmed

•learnt from others

_

Bower birds are artists, leaf-cutting ants practice agriculture, crows use tools, chimpanzees form coalitions against rivals. The only major talent unique to humans is language, the ability to transmit encoded thoughts from the mind of one individual to another. At first glance, language seems to have appeared from nowhere, since no other species speaks. But other animals do communicate. Vervet monkeys have specific alarm calls for their principal predators, like eagles, leopards, snakes and baboons. Researchers have played back recordings of these calls when no predators were around and found that the vervets would scan the sky in response to the eagle call, leap into trees at the leopard call and look for snakes in the ground cover at the snake call. Vervets can’t be said to have words for these predators because the calls are used only as alarms; a vervet can’t use its baboon call to ask if anyone noticed a baboon around yesterday. Still, their communication system shows that they can both utter and perceive specific sounds. Dr. Marc Hauser, a psychologist at Harvard who studies animal communication, believes that basic systems for both the perception and generation of sounds are present in other animals. ”That suggests those systems were used way before language and therefore did not evolve for language, even though they are used in language,” he said. Language, as linguists see it, is more than input and output, the heard word and the spoken. It’s not even dependent on speech, since its output can be entirely in gestures, as in American Sign Language. The essence of language is words and syntax, each generated by a combinatorial system in the brain.

_

Animal communication systems are by contrast very tightly circumscribed in what may be communicated. Indeed, displaced reference, the ability to communicate about things outside immediate temporal and spatial contiguity, which is fundamental to speech, is found elsewhere only in the so-called language of bees. Bees are able, by carrying out various conventionalized movements (referred to as bee dances) in or near the hive, to indicate to others the locations and strengths of nectar sources. But nectar sources are the only known theme of this communication system. Surprisingly, however, this system, nearest to human language in function, belongs to a species remote from man in the animal kingdom and is achieved by very different physiological activities from those involved in speech. On the other hand, the animal performance superficially most like human speech, the mimicry of parrots and of some other birds that have been kept in the company of humans, is wholly derivative and serves no independent communicative function. Humankind’s nearest relatives among the primates, though possessing a vocal physiology similar to that of humans, have not developed anything like a spoken language. Attempts to teach sign language to chimpanzees and other apes through imitation have achieved limited success, though the interpretation of the significance of ape signing ability remains controversial. The Gorilla Koko reportedly uses as many as 1000 words in American Sign Language, and understands 2000 words of spoken English. There are some doubts about whether her use of signs is based in complex understanding or in simple conditioning. Among apes communication generally takes place within a single social group composed of members of both sexes and of disparate ages, who have spent most or all of their lives together. Primates have very good eyesight and much of their communication is accomplished in gestures or body language. The meaning of gestures differs from species to species. The signs of animal systems are inborn. Animal systems are set responses to stimuli. In animal systems, each signal has one and only one function. Animal signals are not naturally used in novel ways. Animal systems are essentially non-creative. Because they are non-creative, animal systems are closed inventories of signs used to express a few specific messages only. Animal systems seem not to change from generation to generation.

_

Dolphins:

It was long believed that dolphins were never able to demonstrate the ability to communicate in their own language, but in a recent discovery, we may have been wrong all along. With the use of a CymaScope researchers have discovered that dolphins are now using their whistles to communicate more than just a simple hello to one another. They are discussing their demographics: names, ages, locations, genders, etc. It only makes sense that one of the world’s most intelligent animals has a language that they use to convey information to one another. Just like each person has his or her own unique voice, each dolphin has its own unique whistle sound, allowing each dolphin to maintain a separate identity, similar to humans. Although this may be nothing spectacular, dolphins are able to create new sounds and whistles when trying to attract a mate. Another interesting point is that in most (if not all) groups, there is a designated leader. The leader is responsible for communicating with other groups’ leaders, discussing possible things such as demographics or locations of food and danger. Remarkably, dolphins can hear one another up to 6 miles apart underwater through a method called echolocation.

_

The argument goes as follows: humans emit sound to communicate; animals emit sounds to communicate, therefore human speech evolved from animal calls. The logic of this syllogism is rather shaky. Its weakness becomes apparent when one examines animal calls and human speech more closely.

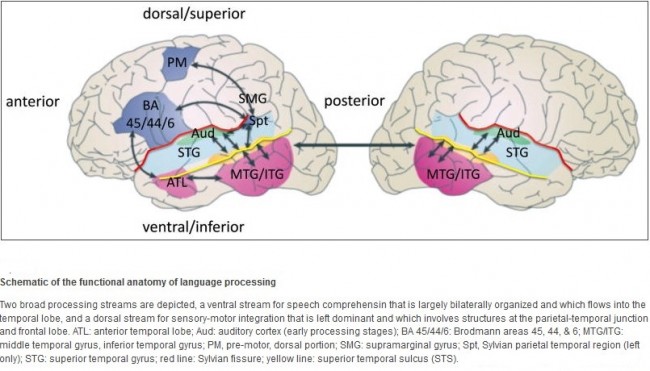

First, the anatomical structures underlying primate calls and human speech are different. Primate calls are mostly mediated by the cingulated cortex and by deep, diencephalic and brain stem structures (see Jürgens, 2002). In contrast, the circuits underlying human speech are formed by areas located around the Sylvian fissure, including the posterior part of IFG. It is hard to imagine how in primate evolution, the call system shifted from its deep position found in non-human primates to the lateral convexity of the cortex where human speech is housed.

Second, speech in humans is not, or is not necessarily, linked to emotional behavior, whereas animal calls are.

Third, speech is mostly a dyadic, person-to-person communication system. In contrast, animal calls are typically emitted without a well-identified receiver.

Fourth, speech is endowed with combinatorial properties that are absent in animal communication. As Chomsky (1966) rightly stressed, human language is “based on an entirely different principle” from all other forms of animal communication. Finally, humans do possess a “call” communication system like that of nonhuman primates and its anatomical location is similar. This system mediates the utterances that humans emit when in particular emotional states (cries, yelling, etc.). These utterances, which are preserved in patients with global aphasia, lack the referential character and the combinatorial properties that characterize human speech.

_

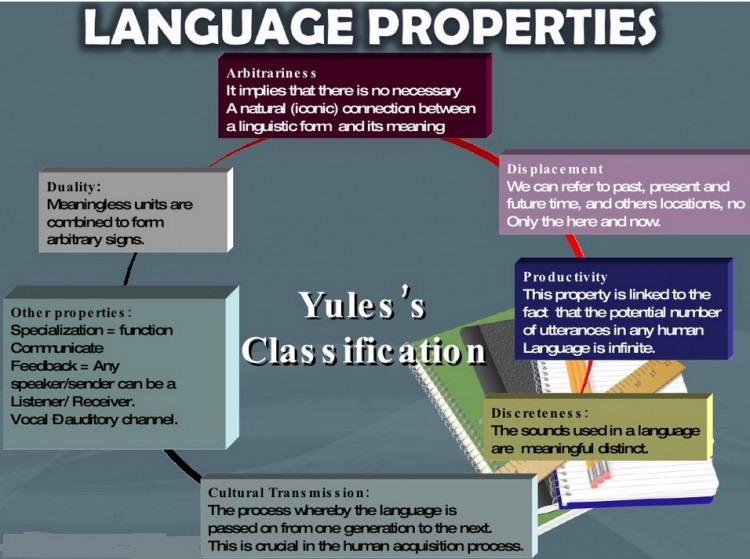

Some linguists (e.g. Chomsky, 1957, Macphail, 1982, both cited in Pearce, 1987) have argued that language is a unique human behaviour and that animal communication falls short of human language in a number of important ways. Chomsky (1957) claims that humans possess an innate universal grammar that is not possessed by other species. This can be readily demonstrated, he claims, by the universality of language in human society and by the similarity of their grammars. No natural non-human system of communication shares this common grammar. Macphail (1982, cited by Pearce, 1987) made the claim that “humans acquire language (and non-humans do not) not because humans are (quantitatively) more intelligent, but because humans possess some species-specific mechanism (or mechanisms) which is a prerequisite of language-acquisition”. Some researchers have provided lists of what they consider to be the criteria that animal communication must meet to be regarded as language. In the 1960s, linguistic anthropologist Charles F. Hockett defined a set of features that characterize human language and set it apart from animal communication. He called these characteristics the design features of language. Hockett originally believed there to be 13 design features. While primate communication utilizes the first 9 features, the final 4 features (displacement, productivity, cultural transmission, and duality) are reserved for humans. Hockett’s thirteen “design-features” for language are as follows:-

1. Vocal-auditory channel: sounds emitted from the mouth and perceived by the auditory system. This applies to many animal communication systems, but there are many exceptions. Also, it does not apply to human sign language, which meets all the other 12 requirements. It also does not apply to written language.

2. Broadcast transmission and directional reception: this requires that the recipient can tell the direction that the signal comes from and thus the originator of the signal.

3. Rapid fading (transitory nature): Signal lasts a short time. This is true of all systems involving sound. It doesn’t take into account audio recording technology and is also not true for written language. It tends not to apply to animal signals involving chemicals and smells which often fade slowly.

4. Interchangeability: All utterances that are understood can be produced. This is different to some communication systems where, for example, males produce one set of behaviours and females another and they are unable to interchange these messages so that males use the female signal and vice versa.

5. Total feedback: The sender of a message also perceives the message. That is, you hear what you say. This is not always true for some kinds of animal displays.

6. Specialisation: The signal produced is specialised for communication and is not the side effect of some other behaviour (eg. the panting of a dog incidentally produces the panting sound).

7. Semanticity: There is a fixed relationship between a signal and a meaning.

8. Arbitrariness: There is an arbitrary relationship between a signal and its meaning. That is, the signal, is related to the meaning by convention or by instinct but has no inherent relationship with the meaning. This can be seen in different words in different languages referring to the same meaning, or to different calls of different sub-species of a single bird species having the same meaning.

9. Discreteness: Language can be said to be built up from discrete units (e.g. phonemes in human language). Exchanging such discrete units causes a change in the meaning of a signal. This is an abrupt change, rather than a continuous change of meaning (e.g. “cat” doesn’t gradually change in meaning to “bat”, but changes abruptly in meaning at some point). Speech loudness and pitch can, on the other hand be changed continuously without abrupt changes of meaning.

10. Displacement: Communicating about things or events that are distant in time or space.

11. Productivity: Language is an open system. We can potentially produce an infinite number of different messages by combining the elements differently. This is not a feature of, for example, the calls of gibbons who have a finite number of calls and thus a closed system of communication.

12. Cultural transmission: Each generation needs to learn the system of communication from the preceding generation. Many species produce the same uniform calls regardless of where they live in the range (even a range spanning several continents). Such systems can be assumed to be defined by instinct and thus by genetics. Some animals, on the other hand fail to develop the calls of their species when raised in isolation.

13. Duality of patterning: Large numbers of meaningful signals (e.g. morphemes or words) produced from a small number of meaningless units (e.g. phonemes). Human language is very unusual in this respect. Apes, for example, do not share this feature in their natural communication systems.

Hockett later added prevarication, reflexiveness, and learnability to the list as uniquely human characteristics. He asserted that even the most basic human languages possess these 16 features.

_

It seems well established that no animal communication system fulfils all of the criteria outlined by Hockett (1960). This is certainly true for the apes. It is also true for most other species such as parrots and may also be true for animals such as dolphins, who have a complex communication system which involves a complex combination of various sounds. We must avoid using features of human language that are physiologically difficult or impossible for the animal to manage. For example, spoken human language is extremely difficult or impossible for most animals because of the structure of their vocal organs. Apes, for example, can’t produce a large proportion of the vowels and would have difficulty with some of the consonants. This may be due not only to the shapes of the vocal organs but also to the limitations of the motor centers in the brain that control these organs. We might attempt, on the other hand, to teach apes language that involves them using their hands (e.g. sign language or the manipulation of symbols). Research with apes, like that of Francine Patterson with Koko (gorilla) or Allen and Beatrix Gardner with Washoe (chimpanzee), suggested that apes are capable of using language that meets some of these requirements such as arbitrariness, discreteness, and productivity. In the wild chimpanzees have been seen “talking” to each other, when warning about approaching danger. For example, if one chimpanzee sees a snake, he makes a low, rumbling noise, signaling for all the other chimps to climb into nearby trees. In this case, the chimpanzees’ communication is entirely contained to an observable event, demonstrating a lack of displacement. Some birds, such as certain parrots and the Indian Hill Mynah, are able to mimic human speech with great clarity. We could, therefore, attempt to teach such animals spoken human language. Dolphins cannot be taught either type of language but may be able to understand sounds or gestures and to respond by pressing specially designed levers.

_

It is increasingly evident that one of the most important factors separating humans from animals is indeed our use of language. The burgeoning field of linguistic research on chimpanzees and bonobos has revealed that, while our closest relatives can be taught basic vocabulary, it is extremely doubtful that this linguistic ability extends to syntax. (Fouts 1972; Savage-Rumbaugh 1987) Chimps like Washoe can be taught (not easily, but reliably) to have vocabularies of up to hundreds of words, but only humans can combine words in such a way that the meaning of their expressions is a function of both the meaning of the words as well as the way they are put together. Even the fact that some primates can be tutored to have fairly significant vocabularies is notable when one considers that such achievements come only after considerable training and effort. By contrast, even small children acquire much larger vocabularies — and use the words far more productively — with no overt training at all. There are very few indications of primates in the wild using words referentially at all (Savage-Rumbaugh 1980), and if they do, it is doubtful whether vocabularies extend beyond 10 to 20 words at maximum (Cheney 1990). Humans are noteworthy for having not only exceptional linguistic skills relative to other animals, but also for having significantly more powerful intellectual abilities. This observation leads to one of the major questions confronting linguists, cognitive scientists, and philosophers alike: to what extent can our language abilities be explained by our general intellectual skills? Can (and should) they really be separated from each other?

___________

Definition of language:

The English word “language” derives ultimately from Old French langage which is from Latin lingua meaning “tongue”. The word is sometimes used to refer to codes, ciphers, and other kinds of artificially constructed communication systems such as those used for computer programming. A language in this sense is a system of signs for encoding and decoding information. Language is a formal system of signs governed by grammatical rules of combination to communicate meaning. This definition stresses that human languages can be described as closed structural systems consisting of rules that relate particular signs to particular meanings. This structuralist view of language was first introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, and his structuralism remains foundational for most approaches to language today. Some proponents of this view of language have advocated a formal approach which studies language structure by identifying its basic elements and then by formulating a formal account of the rules according to which the elements combine in order to form words and sentences. The main proponent of such a theory is Noam Chomsky, the originator of the generative theory of grammar, who has defined language as a particular set of sentences that can be generated from a particular set of rules. Chomsky considers these rules to be an innate feature of the human mind and to constitute the essence of what language is. Another definition sees language as a system of communication that enables humans to cooperate. This definition stresses the social functions of language and the fact that humans use it to express themselves and to manipulate objects in their environment. Functional theories of grammar explain grammatical structures by their communicative functions, and understand the grammatical structures of language to be the result of an adaptive process by which grammar was “tailored” to serve the communicative needs of its users. A language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols by means of which a social group cooperates. Language is a system of conventional spoken or written symbols by means of which human beings, as members of a social group and participants in its culture and expresses themselves. The functions of language include communication, the expression of identity, play, imaginative expression, and emotional release.

_

Many definitions of language have been proposed:

American heritage dictionary defines language as:

1.

a) Communication of thoughts and feelings through a system of arbitrary signals, such as voice sounds, gestures, or written symbols.

b) Such a system including its rules for combining its components, such as words.

c) Such a system as used by a nation, people, or other distinct community; often contrasted with dialect.

2.

a) A system of signs, symbols, gestures, or rules used in communicating: the language of algebra.

b) Computer Science. A system of symbols and rules used for communication with or between computers.

3. Body language; kinesics.

4. The special vocabulary and usages of a scientific, professional, or other group: “his total mastery of screen language-camera placement, editing-and his handling of actors” (Jack Kroll).

5. A characteristic style of speech or writing: Shakespearean language.

6. A particular manner of expression: profane language; persuasive language.

7. The manner or means of communication between living creatures other than humans: the language of dolphins.

8. Verbal communication as a subject of study.

9. The wording of a legal document or statute as distinct from the spirit.

_

Laymen’s definition of language:

—-Language is what we do things with.

—-Language is what I think with.

—-Language is used for communication.

—-Language is what I speak with.

—-Language is what I write with.

….

Pedagogical definition of “language”:

—-Language is a medium of knowledge.

—-Language is a medium of learning.

—-Language is part of one’s cultural quality.

—-Language is part of the many requirements for a future citizen.

—-Language is an element of quality education.

_

Lexicographical definition of language:

The word ‘language’ means differently in different contexts:

1. Language means what a person says or said. e.g.: What he says sounds reasonable enough, but he expressed himself in such bad language that many people misunderstood him. (= concrete act of speaking in a given situation)

2. A consistent way of speaking or writing. e.g.: Shakespeare’s language, Faulkner’s language (= the whole of a person’s language; an individual’s personal dialect called idiolect)

3. A particular variety or level of speech or writing. e.g.: scientific language, language for specific purposes, English for specific purposes, trade language, formal language, colloquial language, computer language.

4. The abstract system underlying the totality of the speech / writing behavior of a community. It includes everything in a language system (its pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, writing, e.g.: the English language, the Chinese language, children’s language, second language. Do you know French?

5. The common features of all human languages, or to be more exact, the defining feature of human language behavior as contrasted with animal language systems of communication, or any artificial language. e.g.: He studies language. (= He studies the universal properties of all speech / writing systems, not just one particular language.)

_

Henry Sweet, an English phonetician and language scholar, stated: “Language is the expression of ideas by means of speech-sounds combined into words. Words are combined into sentences, this combination answering to that of ideas into thoughts.” The American linguists Bernard Bloch and George L. Trager formulated the following definition: “A language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols by means of which a social group cooperates.” Any succinct definition of language makes a number of presuppositions and begs a number of questions. The first, for example, puts excessive weight on “thought,” and the second uses “arbitrary” in a specialized, though legitimate, way.

_

Language is system of conventional spoken or written symbols used by people in a shared culture to communicate with each other. A language both reflects and affects a culture’s way of thinking, and changes in a culture influence the development of its language. Related languages become more differentiated when their speakers are isolated from each other. When speech communities come into contact (e.g., through trade or conquest), their languages influence each other. Language is systematic communication by vocal symbols. It is a universal characteristic of the human species. Nothing is known of its origin, although scientists have identified a gene that clearly contributes to the human ability to use language. Scientists generally hold that it has been so long in use that the length of time writing is known to have existed (7,900 years at most) is short by comparison. Just as languages spoken now by peoples of the simplest cultures are as subtle and as intricate as those of the peoples of more complex civilizations, similarly the forms of languages known (or hypothetically reconstructed) from the earliest records show no trace of being more “primitive” than their modern forms. Because language is a cultural system, individual languages may classify objects and ideas in completely different fashions. For example, the sex or age of the speaker may determine the use of certain grammatical forms or avoidance of taboo words. Many languages divide the color spectrum into completely different and unequal units of color. Terms of address may vary according to the age, sex, and status of speaker and hearer. Linguists also distinguish between registers, i.e., activities (such as a religious service or an athletic contest) with a characteristic vocabulary and level of diction.

_

Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, wherein the definition of language is: A systematic means of communicating ideas or feelings by the use of conventionalized signs, sounds, gestures, or marks having understood meanings” (Davis, 8). This acknowledges that language is not necessarily limited to sounds and that, possibly, (some) other animals are capable of something like it.

_

A language is a mode of expression of thoughts and/or feelings by means of sounds, gestures, letters, or symbols, depending on whether the language is spoken, signed, or written. Thoughts and/or feelings alone by itself cannot be expressed even though thoughts and/or feelings can be understood and perceived by an individual. Language can be both receptive, meaning understanding of somebody’s language; and expressive, means producing your language for other’s to understand. Language is the means by which humans transmit information both within their own brains and to environment (communication). Even though language seems to be part of thought when we speak in our mind (we constantly talk to ourselves in our mind), it is apparently distinct from it. It has been seen that language is much more than the external expression and communication of internal thoughts formulated independently of their verbalization.

_

Some researchers use ‘language’ to denote any system that freely allows concepts to be mapped to signals, where the mapping is bi-directional (going from concepts to signals and vice versa) and exhaustive (any concept, even one never before considered, can be so mapped). Although there is nothing restricting language to humans in this definition, by current knowledge only humans possess a communication system with these properties. Although all animals communicate, and all vertebrates (at least) have concepts, most animal communication systems allow only a small subset of an individual’s concepts to be expressed as signals (e.g. threats, mating, food or alarm calls, etc.).

_

The whole object and purpose of language is to be meaningful. Languages have developed and are constituted in their present forms in order to meet the needs of communication in all its aspects. It is because the needs of human communication are so various and so multifarious that the study of meaning is probably the most difficult and baffling part of the serious study of language. Traditionally, language has been defined, as in the definitions quoted above, as the expression of thought, but this involves far too narrow an interpretation of language or far too wide a view of thought to be serviceable. The expression of thought is just one among the many functions performed by language in certain contexts.

_

My logic is that when you have so many definitions of language by so many experts, it means that there are many ways of understanding language. It also means that understanding of language is elusive.

_

My definition of language:

Language is system of conversion of thoughts, concepts and emotions into symbols bi-directionally (from thoughts, concepts and emotions to symbols and vice versa) and symbols could be sounds, letters, syllables, logograms, numbers, pictures or gestures; and this system is governed by set of rules so that symbols or combination of symbols carry certain meaning that was contained in thoughts, concepts and emotions.

____________

Four basic thoughts are developed:

(1) language serves the speaker as a means of expression, appeal to the audience and description of situations;

(2) language is symbolic, as only certain abstractions are relevant to its function;

(3) language must be described as the actual activity of speaking, as language mechanism, as speech act and as a product of speech;

(4) language is a lexicological as well as a syntactic system.

_

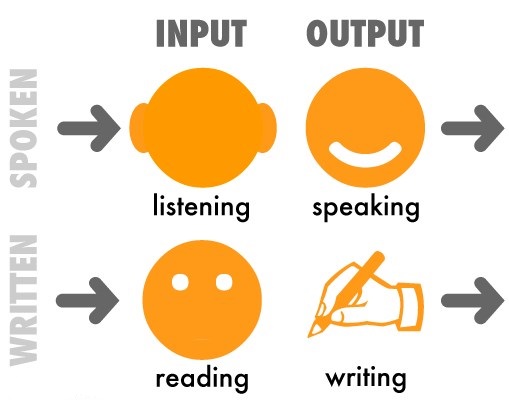

The 4 Language Skills:

When we learn a language, there are four skills that we need for complete communication. When we learn our native language, we usually learn to listen first, then to speak, then to read, and finally to write. These are called the four “language skills”:

The four language skills are related to each other in two ways:

•the direction of communication (in or out)

•the method of communication (spoken or written)

Input is sometimes called “reception” and output is sometimes called “production”. Spoken is also known as “oral”.

Note that these four language skills are sometimes called the “macro-skills”. This is in contrast to the “micro-skills”, which are things like grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and spelling.

The figure below denotes 4 language skills:

_

Receptive Language:

Receptive language is the understanding of language “input.” This includes the understanding of both words and gestures. Receptive language goes beyond just vocabulary skills, but also the ability to interpret a question as a question, the understanding of concepts like “on,” or accurately interpreting complex grammatical forms.

Expressive Language:

Expressive language, is most simply the “output” of language, how one expresses his or her wants and needs. This includes not only words, but also the grammar rules that dictate how words are combined into phrases, sentences and paragraphs as well as the use of gestures and facial expressions. It is important to make the distinction here between expressive language and speech production. Speech production relates to the formulation of individual speech sounds using one’s lips, teeth, and tongue. This is separate from one’s ability to formulate thoughts that are expressed using the appropriate word or combination of words.

____________

Speech in detail:

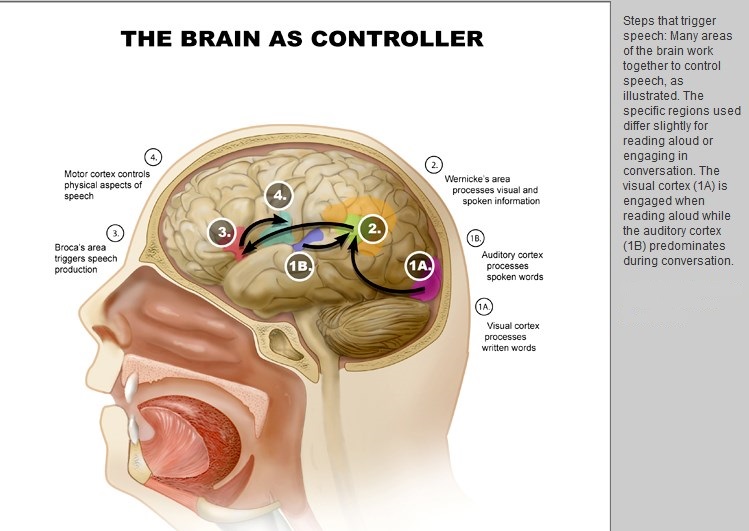

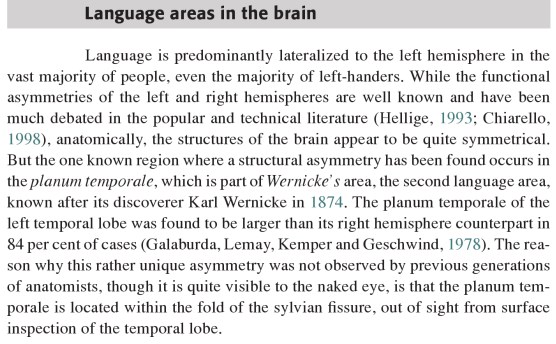

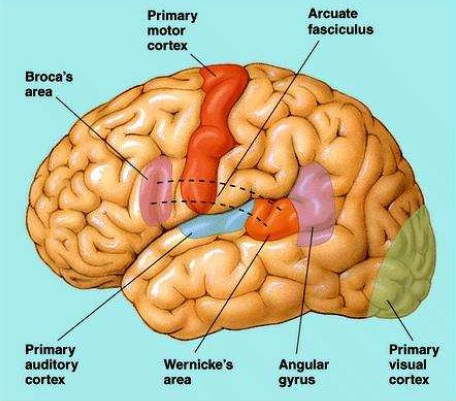

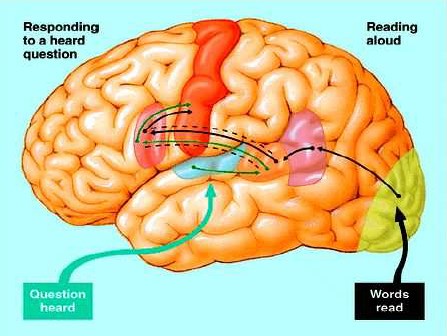

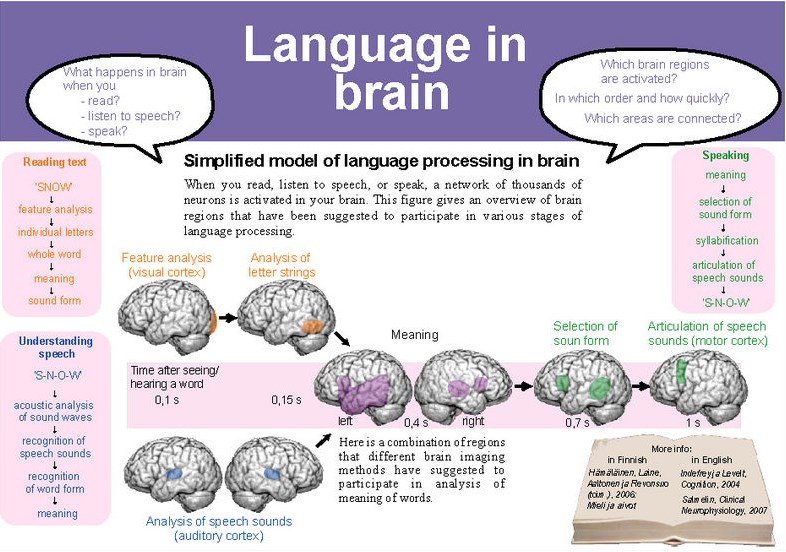

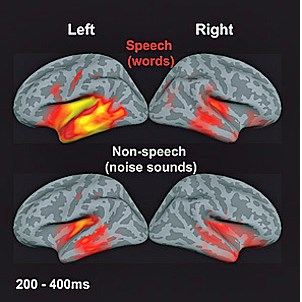

Speech is the vocalized form of human language. It is based upon the syntactic combination of lexical and names that are drawn from very large (usually about 10,000 different words). Each spoken word is created out of the phonetic combination of a limited set of vowel and consonant speech sound units. These vocabularies, the syntax which structures them and their set of speech sound units differ, creating the existence of many thousands of different types of mutually unintelligible human languages. Most human speakers are able to communicate in two or more of them, hence being polyglots. The vocal abilities that enable humans to produce speech also provide humans with the ability to sing. Speech in some cultures has become the basis of a written language, often one that differs in its vocabulary, syntax and phonetics from its associated spoken one, a situation called diglossia. Speech in addition to its use in communication, is also used internally by mental processes to enhance and organize cognition in the form of an interior monologue. Normal human speech is produced with pulmonary pressure provided by the lungs which creates phonation in the glottis in the larynx that is then modified by the vocal tract into different vowels and consonants. However humans can pronounce words without the use of the lungs and glottis in alaryngeal speech of which there are three types: esophageal speech, pharyngeal speech and buccal speech (better known as Donald Duck talk). Speech perception refers to the processes by which humans are able to interpret and understand the sounds used in language. Spoken speech sounds travel in air and enter ear of listener where sounds are converted into electrical impulse and transmitted to auditory cortex. Auditory cortex transmits speech to Wernicke’s area. Two areas of the cerebral cortex are necessary for speech. Broca’s area, named after its discoverer, French neurologist Paul Broca (1824-1880), is in the frontal lobe, usually on the left, near the motor cortex controlling muscles of the lips, jaws, soft palate and vocal cords. When damaged by a stroke or injury, comprehension is unaffected but speech is slow and labored and the sufferer will talk in “telegramese”. Wernicke’s area, discovered in 1874 by German neurologist Carl Wernicke (1848-1904), lies to the back of the temporal lobe, again, usually on the left, near the areas receiving auditory and visual information. Damage to it destroys comprehension – the sufferer speaks fluently but nonsensically. Spoken vocalizations are quickly turned from sensory inputs into motor instructions needed for their immediate or delayed (in phonological memory) vocal imitation. This occurs independently of speech perception. This mapping plays a key role in enabling children to expand their spoken vocabulary and hence the ability of human language to transmit across generations.

_

The speech can be categorized into various types:

_

Spoken language:

Spoken language, sometimes called oral language, is language produced in its spontaneous form, as opposed to written language. Many languages have no written form, and so are only spoken. In spoken language, much of the meaning is determined by the context. This contrasts with written language, where more of the meaning is provided directly by the text. In spoken language the truth of a proposition is determined by common-sense reference to experience, whereas in written language a greater emphasis is placed on logical and coherent argument; similarly, spoken language tends to convey subjective information, including the relationship between the speaker and the audience, whereas written language tends to convey objective information. The relationship between spoken language and written language is complex. Within the field of linguistics the current consensus is that speech is an innate human capability while written language is a cultural invention. However some linguists, such as those of the Prague school, argue that written and spoken language possess distinct qualities which would argue against written language being dependent on spoken language for its existence. The term spoken language is sometimes used for vocal language (in contrast to sign language), especially by linguists.

_

Speech to writing:

For an adequate understanding of human language, it is necessary to keep in mind the absolute primacy of speech. In societies in which literacy is all but universal and language teaching at school begins with reading and writing in the mother tongue, one is apt to think of language as a writing system that may be pronounced. In point of fact, language is a system of spoken communication that may be represented in various ways in writing. The human being has almost certainly been in some sense a speaking animal from early in the emergence of Homo sapiens as a recognizably distinct species. The earliest-known systems of writing go back perhaps 4,000 to 5,000 years. This means that for many years (perhaps hundreds of thousands) human languages were transmitted from generation to generation and were developed entirely as spoken means of communication. In all communities, speaking is learned by children before writing, and all people act as speakers and hearers much more than as writers and readers. It is, moreover, a total fallacy to suppose that the languages of illiterate or so-called primitive peoples are less structured, less rich in vocabulary, and less efficient than the languages of literate civilizations. The lexical content of languages varies, of course, according to the culture and the needs of their speakers, but observation bears out the statement that the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir made in 1921: “When it comes to linguistic form, Plato walks with the Macedonian swineherd, Confucius with the head-hunting savage of Assam.” All this means that the structure and composition of language and of all languages have been conditioned by the requirements of speech, not those of writing. Languages are what they are by virtue of their spoken, not their written, manifestations. The study of language must be based on knowledge of the physiological and physical nature of speaking and hearing.

_

Writing:

Next, it is important to define “writing” and determine how it differs from earlier proto-writing. Writing can be described as “a system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought”. It is a widely-established and complex system that all speakers of that particular language can read (or at least recognize as their written language). According to The History of Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, “writing includes both the holistic characteristics of visual perception, and at the same time, without contradiction, the sequential character of auditory perception. It is at once a temporal, iconic and symbolic”. Writing is clearly more advanced than proto-writing, pictograms, and symbolic communication, which should also be briefly classified. Ice Age signs and other types of limited writing could be designated as “proto-writing.” This type of communication was long before any systems of full writing were developed. In short, proto-writing can involve the use of pictures or symbols to convey meaning. This form of early writing could relate an idea, but the system was not elaborate, complete, or fully evolved. A group of clay tablets from the Uruk period, probably dating to 3300 BC, model these properties of proto-writing. The tablets mostly deal with numbers and numerical amounts; most of the symbols are pictographic in nature. Nothing that could be identified as true writing is evident. So, this form of communication can convey certain concepts well enough, but it isn’t capable of expressing more abstract ideas, nor is it necessarily standardized.

_

Writing system:

Throughout history a number of different ways of representing language in graphic media have been invented. These are called writing systems. The use of writing has made language even more useful to humans. It makes it possible to store large amounts of information outside of the human body and retrieve it again, and it allows communication across distances that would otherwise be impossible. Many languages conventionally employ different genres, styles, and register in written and spoken language, and in some communities, writing traditionally takes place in an entirely different language than the one spoken. There is some evidence that the use of writing also has effects on the cognitive development of humans, perhaps because acquiring literacy generally requires explicit and formal education. The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic period of the late 4th millennium BC. The Sumerian archaic cuneiform script and the Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally considered to be the earliest writing systems, both emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from 3400–3200 BC with the earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BC. It is generally agreed that Sumerian writing was an independent invention; however, it is debated whether Egyptian writing was developed completely independently of Sumerian, or was a case of cultural diffusion. A similar debate exists for the Chinese script, which developed around 1200 BC. The pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems (including among others Olmec and Maya scripts) are generally believed to have had independent origins.

_

The writing systems are composed of diverse symbolisms.

There are four types of writing:

1. Ideographic: idea expressed through a symbol (Egyptian hieroglyph, Chinese)

2. Pictographic: idea expressed through an image (nahuati!)

3. Alphabetic: one sound corresponds to one symbol (latin)

4. Syllabic: one symbol corresponds to syllables

_

Writing systems represent language using visual symbols, which may or may not correspond to the sounds of spoken language. The Latin alphabet (and those on which it is based or that have been derived from it) was originally based on the representation of single sounds, so that words were constructed from letters that generally denote a single consonant or vowel in the structure of the word. In syllabic scripts, such as the Inuktitut syllabary, each sign represents a whole syllable. In logographic scripts, each sign represents an entire word, and will generally bear no relation to the sound of that word in spoken language. Because all languages have a very large number of words, no purely logographic scripts are known to exist. Written language represents the way spoken sounds and words follow one after another by arranging symbols according to a pattern that follows a certain direction. The direction used in a writing system is entirely arbitrary and established by convention. Some writing systems use the horizontal axis (left to right as the Latin script or right to left as the Arabic script), while others such as traditional Chinese writing use the vertical dimension (from top to bottom). A few writing systems use opposite directions for alternating lines, and others, such as the ancient Maya script, can be written in either direction and rely on graphic cues to show the reader the direction of reading. In order to represent the sounds of the world’s languages in writing, linguists have developed the International Phonetic Alphabet, designed to represent all of the discrete sounds that are known to contribute to meaning in human languages.

_

Alphabetic system represents consonants and vowels (alphabets) while syllabaries represent syllables, though some do both. There are a number of subdivisions of each type, and there are different classifications of writing systems in different sources. Abjads, or consonant alphabets, have independent letters for consonants and may indicate vowels using some of the consonant letters and/or with diacritics. In Abjads such as Arabic and Hebrew full vowel indication (vocalisation) is only used in specific contexts, such as in religious books and children’s books. Syllabic alphabets, alphasyllabaries or abugidas are writing systems in which the main element is the syllable. Syllables are built up of consonants, each of which has an inherent vowel, e.g. ka, kha, ga, gha. Diacritic symbols are used to change or mute the inherent vowel, and separate vowel letters may be used when vowels occur at the beginning of a syllable or on their own. A syllabary is a phonetic writing system consisting of symbols representing syllables. A syllable is often made up of a consonant plus a vowel or a single vowel.

_

Semanto-phonetic writing systems:

The symbols used in semanto-phonetic writing systems often represent both sound and meaning. As a result, such scripts generally include a large number of symbols: anything from several hundred to tens of thousands. In fact there is no theoretical upper limit to the number of symbols in some scripts, such as Chinese. These scripts could also be called logophonetic, morphophonemic, logographic or logosyllabic. Semanto-phonetic writing systems may include the following types of symbol:

Pictograms and logograms:

Pictograms or pictographs resemble the things they represent. Logograms are symbols that represent parts of words or whole words. The Chinese characters used to look like the things they stand for, but have become increasingly stylized over the years.

Ideograms:

Ideograms or ideographs are symbols which graphically represent abstract ideas.

Compound characters:

The majority of characters in the Chinese script are semanto-phonetic compounds: they include a semantic element, which represents or hints at their meaning, and a phonetic element, which shows or hints at their pronunciation.

__

Written language:

A written language is the representation of a language by means of a writing system. Written language is an invention in that it must be taught to children; children will pick up spoken language (oral or sign) by exposure without being specifically taught. A written language exists only as a complement to a specific spoken language, and no natural language is purely written. However, extinct languages may be in effect purely written when only their writings survive.

_

Differences between writing and speech: written vs. spoken languages:

Written and spoken languages differ in many ways. However some forms of writing are closer to speech than others, and vice versa. Below are some of the ways in which these two forms of language differ:

•Writing is usually permanent and written texts cannot usually be changed once they have been printed/written out. Speech is usually transient, unless recorded, and speakers can correct themselves and change their utterances as they go along.

•A written text can communicate across time and space for as long as the particular language and writing system is still understood. Speech is usually used for immediate interactions.

•Written language tends to be more complex and intricate than speech with longer sentences and many subordinate clauses. The punctuation and layout of written texts also have no spoken equivalent. However some forms of written language, such as instant messages and email, are closer to spoken language. Spoken language tends to be full of repetitions, incomplete sentences, corrections and interruptions, with the exception of formal speeches and other scripted forms of speech, such as news reports and scripts for plays and films.

•Writers receive no immediate feedback from their readers, except in computer-based communication. Therefore they cannot rely on context to clarify things so there is more need to explain things clearly and unambiguously than in speech, except in written correspondence between people who know one another well. Speech is usually a dynamic interaction between two or more people. Context and shared knowledge play a major role, so it is possible to leave much unsaid or indirectly implied.

•Writers can make use of punctuation, headings, layout, colours and other graphical effects in their written texts. Such things are not available in speech. Speech can use timing, tone, volume, and timbre to add emotional context.

•Written material can be read repeatedly and closely analysed, and notes can be made on the writing surface. Only recorded speech can be used in this way.

•Some grammatical constructions are only used in writing, as are some kinds of vocabulary, such as some complex chemical and legal terms. Some types of vocabulary are used only or mainly in speech. These include slang expressions, and tags like y’know, like, etc.

_