Dr Rajiv Desai

An Educational Blog

ARE ORDINARY PEOPLE BAD?

Are ordinary people bad?

________

_______

Let me start by giving 3 examples from India:

_

_

Example-1

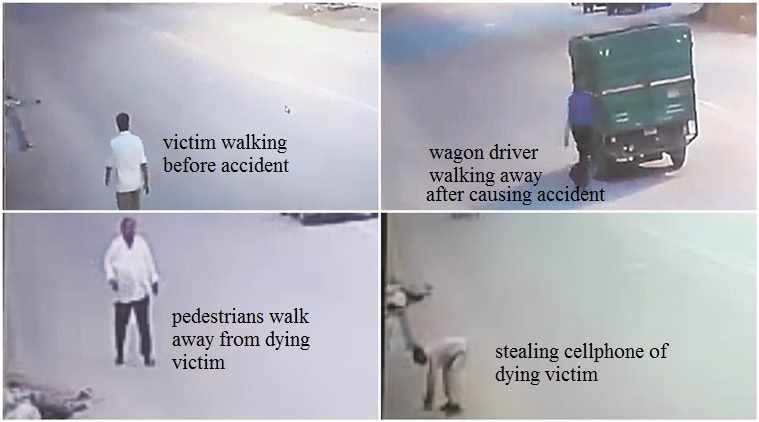

On August 10, 2016 Matibool is on his way home from an overnight shift as a watchman, carrying a cellphone in his hand as seen in the figure above. It is dawn in Delhi. Suddenly, a speeding three-wheeled tempo barrels down on him from behind, knocking him into the air. The driver gets out, sees Matibool’s crumpled body and decides against even approaching him. In a matter of seconds, the driver is back in the truck, and away he goes. As Matibool lay bleeding for an hour, men and women riding in 140 cars and 82 rickshaws would avoid his dying body. So would 181 bikers and 45 pedestrians. At one point, an emergency response van used by the Delhi police drives by. A cycle rickshaw passes his body and stops a little bit down the road. A passenger alights, walks by Matibool and steals his cellphone and gets back on the rickshaw and leaves. I am rudely reminded of how deeply the malaise of cruelty, corruption and total numbness & indifference to humanity affects ordinary people. The man eventually died leaving behind a helpless young family.

_

Example-2

From 14 to 17 June 2013, the Indian state of Uttarakhand and adjoining areas received heavy rainfall, which was about 375% more than the benchmark rainfall during a normal monsoon. This caused the melting of Chorabari Glacier at the height of 3800 metres, and eruption of the Mandakini River which led to heavy floods. Although the Kedarnath Temple itself was not damaged, its base was inundated with water, mud and boulders from the landslide, damaging its perimeter. Many hotels, rest houses and shops around the temple in Kedarnath Township were destroyed, resulting in several casualties. The hundreds and thousands returning to safety from the rain ravaged Kedar Valley and other parts of devastated Uttarakhand have stories to narrate of human insensitivity, as many locals were fleecing the trapped pilgrims and tourists in the wake of shortages of food supply, shelter, medicines and drinking water. Those who survived the cloudburst and flood limped back home with harrowing tales of spending four days without food and water, being forced to pay Rs.200 for a Rs.5 biscuit packet, and Rs.100 for a Rs.10 water bottle.

_

Example-3

The Indian government’s demonetisation decision on 8th November 2016 has led to a windfall for 47 municipalities, pushing up their total tax revenue for November 2016 to over two and a half times the sum collected in November last year. By 22nd November 2016, the municipal tax collection for the 47 civic bodies had reached Rs.13,192 crore. [One crore = 10 million] Last November, the municipalities had collected just Rs.3,607 crore. Mumbai has the maximum share of the increased tax collection at Rs.11,913 crore, which is 90% of the total revenue. This is over three times Mumbai’s collection for 2015. Hyderabad accounts for the maximum increase — 26 times the tax collection in November 2015. Surat’s tax revenue of Rs 100 crore marked a nearly 14-fold increase. Recent analysis of data from the 450 municipalities shows how almost every municipal body saw increase in collection of property tax and other user charges such as water bill and sewage charges. This dramatic change happened as a result of the decision to demonetise the old Rs.500 and Rs.1,000 notes. These ordinary people were defaulters and wilfully did not pay municipality tax for years. Now suddenly their money in denomination of Rs.500 and Rs.1000 are illegal tender, so they got rid of it by paying municipality tax. This is double immorality; first by not paying municipality tax for years and second by converting unaccounted black money into accounted white money by paying municipality tax with illegal notes. Remember, these so called ‘ordinary people’ also have black money which they converted into white by paying municipality tax. Except salaried class, most ordinary people hardly pay any income tax at all in India.

_

Now let us discuss why and how majority of ordinary people are extraordinarily immoral and dishonest:

______

Note:

The word ‘nature’ is used frequently in this article. One meaning of ‘nature’ is biology or genetics, for example nature versus nurture debate. Another meaning of ‘nature’ is character or personality, for example human nature is good by default. Please do not mix up these two different meanings. See the context in which the word ‘nature’ is used.

______

______

Integrity is doing the right thing, even when no one is watching.

-C. S. Lewis

___

Our ability to selectively engage and disengage our moral standards…helps explain how people can be barbarically cruel in one moment and compassionate the next.

-Albert Bandura

___

You’re only a victim once. The next time you’re an accomplice.

-Naomi Judd

______

______

Introduction to ‘are ordinary people bad’:

According to the worldview that prevails in our culture, most people are naturally good, because nature is good. The monstrosities of the world are caused by the few people (like Hitler or Idi Amin) who are fundamentally warped and evil. This worldview gives us an easy conscience, because we don’t have to contemplate the evil in ourselves. But when somebody who seems mostly good does something completely awful, we are rendered mute or confused. We always say, “If people were just nicer to each other the world would be a very different place.” But when we say nicer are we really just referring to behaving in a way that is honest? We all aspire to be good people, but thinking good thoughts and acting in accordance with them are two separate things. Think about the last time you wanted to call in sick to work and weren’t really ill, or were involved in a home sale and tweaked the negations in your favour. How did you actually come up with the decision? These common ethical dilemmas appear in every facet of our lives, from personal to professional to political. It’s no surprise that unethical behaviour is widespread in our society, as acting dishonestly sometimes “gets you ahead.”

_

Morality is a term that refers to our adherence to rules that govern human behavior on the basis of some idea of right and wrong. Ethics refers to our process of reasoning about moral rules. Whatever your concept of morality, it must address the human capacity to identify and choose between right and wrong and then to act accordingly. People don’t want to think of themselves as bad, so when faced with the unavoidable prospect of doing something they’d normally consider morally objectionable, they often start finding ways to justify it. Most people think of themselves as moral and ethical. And yet, major fraud and unethical behaviour is widespread. An in-depth study of ordinary people over an extended period of time reveals how easy it is for ‘good’ people, starting with an initial small, self-justified deception, to quickly justify bigger and bigger indiscretions, thus falling down the ‘slippery slope’ to major unethical behaviour.

_

“What makes good people do bad things?” This is a question that has vexed thinking people throughout history. We all have probably witnessed acquaintances suddenly behaving in uncharacteristically ugly ways. In fact, we need to look no further than the mirror to find living evidence for humanity’s susceptibility to immorality. The vast majority of people have the potential for both doing great good and great evil. Perfectly normal, ordinary people can be pushed in the direction of evil by circumstances, and by being put in a particular environment or position with respect to others. As the story goes, Dr. Jekyll uses a chemical to turn into his evil alter ego Dr. Hyde. In real life, however, no chemical may be needed: Instead, just the right dose of certain social situations can transform ordinary people into evildoers, as was the case with Iraqi prisoner abusers at Abu Ghraib. But are there some people who are inherently bad and can’t be redeemed? Probably yes. Psychopaths may belong in this category. But certainly they are a very small fraction of human society. And determining who is truly a psychopath and not a “misguided” person, drawn to do evil by circumstances, is not easy.

_

Is it possible for a good person to turn evil?

Do you think you have an inner demon that could be triggered to make you rob a bank, steal from a neighbor or torture another human being?

History is replete with entire groups of people, organizations, and nations, engaging in horrific, immoral behavior, ranging from genocide, to riots and killings, to massive greed and corruption. Often, these are not the actions of individuals, but of collective groups led by a toxic leader. All too often, we point the finger at the leader as the cause of the bad behavior, but without willing followers, the destruction would never occur. We are trained, from the time we are kids, to be obedient to authority, and usually that’s good: our parents, our teachers and our priests. The problem is not all authority is just. In many of these cases, the leaders and followers are not initially bad or corrupt people. Various processes occur that allow leaders and followers to disengage their moral reasoning and principals, and justify their bad behavior. Although people believe they are more moral than they actually are, in reality the process of moral disengagement leads them to act immorally, and justify their bad behavior. Justification of bad behavior occurs in a variety of ways. First, we begin to focus on desired outcomes, and rationalize the means to achieve them. If an outcome is important, we begin to believe that the “ends justify the means.” For example, the torturing of suspected terrorists (i.e., waterboarding), is justified because of the desired outcome of protecting citizens from terrorist attacks. ISIS also uses the same process to justify the killing of Westerners as an “acceptable” means of achieving their ends. This “deactivation of moral standards” is a slippery slope that leads only to increases in bad behavior. Another way we justify immoral behavior is through using “euphemistic language.” So, killed or injured civilians in bombing or drone attacks are referred to as “collateral damage.” Likewise, it is easier to imprison or execute a journalist or tourist if the government labels the person a “subversive” or a “spy.” Another means by which people justify their bad behavior is through “advantageous comparisons.” They downplay their own bad behavior by comparing it to the even worse behavior by others (“sure I stole a small amount of money, but my boss really took the company for big bucks.”). Often, people behave badly through diffusion of responsibility. This explains crowd behavior, such as looting during riots (“everybody was doing it”), or hazing behavior (“it’s a tradition, and I was hazed when I was a newcomer”). Bad behavior also occurs, and our moral reasoning fails us, through devaluing of the victims (“they started it”; “they deserved it”). Processes such as these lead to an escalation of violence (“he pulled out a knife, so I pulled out my gun”). Minorities are often considered different and less deserving. Once you buy into that, it is easy to dismiss when they are treated poorly. Throughout history, countries continue to dehumanize the enemy to rally people to accept otherwise unacceptable behavior supposedly needed to defeat the enemy. Because people want to belong, be loyal or patriotic, they go along with the group for it takes tremendous courage to be the lone person to dissent.

_

‘The (human) heart is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked’ – Jeremiah 17 v 9.

If you do not believe this you will never make any sense of this world. Whilst others are looking on people will curb their tendencies, but they put them behind closed doors and they gravitate towards doing wrong – proved time and again all over the world throughout history. However, to combat this tendency means facing up to what is inherent in people and since this is unpalatable the good Professor will probably waste his life looking for non-existent “corrosive social causes”. Compared with most animals, we humans engage in a host of behaviours that are destructive to our own kind and to ourselves. We lie, cheat and steal, carve ornamentations into our own bodies, stress out and kill ourselves, and of course kill others. Science has provided much insight into why an intelligent species seems so nasty, spiteful, self-destructive and hurtful.

__

If everybody is cheating, why not me?

Thomas Hurka, who holds the Henry N.R. Jackman Distinguished Chair in Philosophical Studies at the University of Toronto, says, “Most people have multiple reasons for acting in accordance with moral principles. It’s complex, and the complex can unravel.” According to Hurka, when the mind that might decide to cheat chooses not to, there are two essential factors at work. The first is self-interest – a fear of punishment. “People decide not to cheat in business,” says Hurka, “because they think they won’t get away with it.” As rationales go, it might not inspire heroic string music, but it’s effective. The second reason is subtler. “There are a lot of people who will act rightly, even at some cost to themselves,” says Hurka, “so long as they believe that other people are doing it, too.” This reasoning falls into what American social scientist Jon Elster, in his book The Cement of Society, calls “the norm of fairness.” In deciding whether or not to cheat, a person looks across the desk at her colleagues; if they’re keeping their hands out of the till, she likely will, too. But now that we understand our mind’s typical motivations for good, we can start to see how they might break down. Let’s take fear of punishment first. In order to worry about getting caught, the mind on the brink of an unethical decision has to think getting caught is a real possibility. That requires clear and effective policing, or, as it’s called in the world of business, “governance.” According to Melissa Williams, associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto, who has a deep interest in ethical issues, the understanding that only a watchful eye keeps the populace in line informs a good deal of constitutional thought. People are morally imperfect, goes the thinking, and well-designed institutions free us from having to hope for the best from the shady characters who run them. Immanuel Kant, James Madison, Adam Smith and other philosophers, says Williams, have fashioned arguments around the premise that “a well-ordered constitutional society could govern even a nation of devils.” Once the self-interested people start to cheat,” says Professor Hurka, “that affects the people who believe in fairness, because they’re prepared to do what’s right only so long as other people are doing it. And so they start to cheat.” The norm of fairness not only allows cheating in that scenario, it encourages it. When others are cheating and getting away with it, the norm of fairness says it must be all right. Now you can start to see how a society can experience waves of scandal, in business, in sport and elsewhere. “The existence of the motivation of fairness or reciprocity,” says Hurka, “explains why there can be these swings in moral and immoral behaviour.” The media have a role to play here, too. In general, we have no way of knowing whether our fellow citizens are behaving ethically, but we are swayed by what we see on the news. And every time a scandal story breaks, the norm of fairness applies its effect. Even those perp walks, while increasing the fear of getting caught, reinforce the notion that everyone is cheating. “If the media concentrate on acts of wrongdoing,” says Hurka, “they will create the belief that wrongdoing is common, which will increase the amount of wrongdoing.” This was the quandary faced by India’s four-term Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru when he was pushed to condemn corruption in his own government. In a quote remembered in Jon Elster’s The Cement of Society, Nehru complained, “Merely shouting from the house-tops that everybody is corrupt creates an atmosphere of corruption…. The man in the street says to himself: ‘well, if everybody seems corrupt, why shouldn’t I be corrupt?’”

_

In The Cheating Culture, Callahan devotes a chapter to dishonest students and reports the results of a 2001 study of 1,000 business students on six campuses. It concluded that “students who engaged in dishonest behaviour in their college classes were more likely to engage in dishonest behaviour on the job.” It makes sense to us, intuitively, that people who have cheated before will cheat again. But we make a mistake if we dismiss the cheater as merely a bad apple. Barbara Ley Toffler knows it isn’t true. She was there, at the accounting firm Arthur Andersen, when its leaders made the decisions that linked the firm inextricably to the Enron scandal and ultimately brought it down. She went into that company with high ethical standards, and was appalled at some of the practices she witnessed. But under the influence of the corporate culture, the norm of fairness and the rest of the factors we’ve looked at, it wasn’t long before her standards changed. “I didn’t break any laws or violate regulations,” she writes in Final Accounting, “but I certainly compromised many of my values…. If you hang around a place long enough, you inevitably start to act like most of the people around you.” Toffler now conducts orientation sessions on ethics with MBA students, and one of those students told her something she wants us to hear: “I believe anyone has the potential to be a bad apple.” The mind we’ve been looking at has no evil intent; it thinks of itself, its motivations, as good. And the terrible choice it’s about to make? It might just seem the best decision of all.

_______

Why ordinary people do Bad Things:

Well, there are a handful of explanations, really. Some of the driving forces behind why we do things that we know are bad for us.

- Oppression:

At times people feel driven by force of circumstance to do what they otherwise would not do and some may even commit criminal acts in an effort to bring about what they perceive as solutions to hardships and injustices.

- Money:

The old adage, every man has his price, implies that even good people are willing to violate the rules of decency and morality when enough money is involved. Some who appear amiable and kind under normal circumstances seem to undergo a personality change when money is at stake, transforming themselves into obnoxious and hostile characters. Think of the many crimes that are rooted in greed—blackmail, extortion, fraud, kidnapping, and even murder.

- Getting away:

There is a human tendency to think that one can get away with anything when those in authority are not watching. This is true of people speeding on the highway, cheating on exams, embezzling public funds, and worse. When enforcement is lax or when fear of getting caught is absent, people who are normally law-abiding may feel emboldened to do what they otherwise would not do. “The ease with which criminals get away unpunished,” observes the magazine Arguments and Facts, “seems to inspire ordinary citizens to commit the most brutal of crimes.”

- Temptations:

All humans are susceptible to wrong thinking. Every day, we are bombarded with countless suggestions and temptations to do wrong.

- Peer Pressure:

We’ve all succumbed to peer pressure at some point or another and it’s only natural to wish to appease those around us in an attempt to fit in. Peer pressure is no joke and its influence can sway individuals and entire communities alike.

- Conditioning:

Habits can be hard to break, but conditioning can be flat-out dangerous and seemingly impossible to alter. Once you’ve done something for so long or have been a part of an environment so consistently, there is a chance that you may never open your eyes to an obvious truth or break the cycle to which you’ve become so accustomed. Sometimes, it’s just how we’re raised. Often, we become conditioned to think, feel and act certain ways, due to the result of an impactful event in our past.

- Denial:

Have you ever known someone who continuously makes bad decisions, yet refuses to admit he or she has a problem? Sure, we all have. Denial can be dangerous in any dose. Sometimes, it takes others to intervene in order to help someone realize he or she may be headed down a slippery slope.

- Misinformation:

Sometimes, it’s hard to make certain decisions in good faith when we don’t know all of the facts or if we are simply misinformed. What we perceive as good, or better, may actually turn out to be the polar opposite.

- Bad feels Good:

You simply can’t deny it. Sometimes, bad just feels so good. We’ve all been there. You eat bowl of ice cream and tell yourself it’s low fat, so you’re in the clear, even though the calorie-count you just ignored offers opposing information. Sometimes, things just feel good when you’re in the moment. It isn’t until you’re paying the consequences later on that you begin to have doubts.

- Desperation:

Being desperate is the worst of the irrational defence mechanisms. When a person feels like they have to go to extreme measures, they often will, at the expense of everything and everyone around them. Desperate people can destroy their lives horrifically quickly.

- Boredom:

Boredom is a powerful motivator. When your brain feels like it’s slowing down against its will, it will tell you that you need excitement that you don’t really need. People, when overly bored, will find all kinds of unnecessary and harmful behaviors that supplement their otherwise bland existence — especially if they are used do a fast paced lifestyle. Slowing down is strange for them. Instead of enjoying the silence, they tend to create chaos.

- Ignorance:

Ignorance will drive people to do harmful things that destroy the rest of their life. Lack of awareness about options and opportunities and people who can help force people to do things that are damaging and have long-lasting consequences.

- Shamelessness:

Another cause for our self-destructiveness is unacknowledged and unprocessed shame, that abundant storehouse of negative messages we have received from those around us. One reason for the popularity of courtroom TV, reality shows, shock jock radio, and gossip rags is that they all deliver an unconscious outlet for the toxic hatred and criticism we have about ourselves. We deactivate the shame app in our personal software.

________

________

Studies on cheating by ordinary humans:

_

- Experts who study the ethical makeup of societies always mark off a portion of the populace who can be counted on to do no wrong. According to Professor Leonard Brooks of the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management, the forensic accountant’s rule of thumb holds that “20 per cent of people in general will not steal anything, even if they have a chance.” Those are ones who snarl at temptation. Out of remaining 80 %, Professor Brooks says, “60 per cent will steal if they think there’s a good chance they won’t get caught.” Once the enforcement mechanism is weakened, the segment of the population that was restrained from immoral behaviour only by the fear of “getting caught” starts to get a little frisky. Our mind, ever alert to outside influences, can’t help but notice the ethical shift. And then the “norm of fairness” breaks down.

_

- A study was conducted by psychologists Edward Diener at the University of Illinois and Mark Wallbom at the University of Washington where participants were taking a test with the explicit instruction to not go more than five minutes. The experimenter then set a timer bell for five minutes, left the room, and watched what happened through a two-way mirror. 71% of participants kept going after the bell sounded – hardly a display of honest behavior on their part. In the same study, there was also a separate group of participants, where each one would take the same test in the same room, except that this time the person was seated directly in front of a two-way mirror and, “thus saw themselves whenever they glanced up”. The result? Only 7% of participants cheated. This is a startling difference – 71% versus 7%, where the only difference is the presence of a mirror in front of the participants. The participants suspected that someone is watching through mirror, so behaved honestly.

_

- Unethical behaviour can be contagious:

It’s an interesting question, how observing the questionable behaviour of others affects our own actions. Multiple, viable hypotheses exist. Perhaps seeing someone else get away with something convinces you that the odds of getting caught are lower than you previously figured. Maybe seeing others behave poorly loosens the social conventions that otherwise pressure you into behaving well. Or it could be that seeing the transgressions of others simply brings the notion of ethics to the forefront of your mind. It turns out that a key determinant on this question is who is the unethical role model? Francesca Gino, now at Harvard, and colleagues investigated this by having students complete a task on which they could cheat in order to earn more money. Upon seeing cheating from another student from their own school—wearing university paraphernalia—students became more likely to cheat themselves. It would seem that seeing someone you affiliate with engage in unethical behavior can make you view cheating as less problematic. But witnessing a student from a rival school cheating had the opposite effect. Students became less likely to cheat in this scenario, indicating that when the cheater in your midst is part of them instead of us, bad behaviour can make prevailing ethical standards more salient.

_

- Akbar and Birbal Tale:

Akbar was a ruler in India during the 1500s and Birbal was his advisor. The emperor Akbar was curious about the character of his subjects. Birbal advised him that wise men all think alike, and they are tempted to be dishonest. Akbar disagreed and they put the claim to a test. Birbal invited 100 men to the palace. They were told to return the next day with one pail of milk each. Each person would pour the milk into a well and so all the milk would be collected for the emperor. The men agreed and went home. The next day one of the men was preparing to go to the palace. He was about to fill his pail with milk when he thought about the situation. He thought, all of the milk is going to be pooled collectively into the well. So if everyone else is bringing milk, then what harm is it if I bring a pail of water instead? Surely no one will notice a single pail of water diluting the milk. Therefore, I will bring a pail of water and keep the milk for myself. That day all the men went to the palace and filled up with well with their pails. At night Akbar and Birbal went to the well. When they inspected it, it was completely full of water! Birbal pointed out that each man had thought to cheat the plan by diluting the well with water. But since everyone had the same thought, it turned out that no one ended up bringing milk.

_______

_______

Are humans inherently good?

Arguments in favour of ‘yes’:

The true question here would be if morality is due to the influence of society or if society was only created as a guideline to our morality. Kind of like a chicken or the egg question. The only way society could have ever existed is with the unity of people and inherent goodness within us. The fact that humans may be born good and have slowly been corrupted by society, or that they have been born bad and have been kept in check by laws is unknown. It is such a fundamental question that there has been no solid evidence to whether humans are good or evil. Hurricane Katrina showed that instead of angry mobs looting everything, humans band together in times of crisis to help each other. Humans are naturally inclined to feel compassion and love for others, and this is the case unless something unnatural occurs and disrupts a person’s life. People never hear about a person whom kills just to kill. There is always a reason on why. We are all inherently good to begin and those who become “evil” only do so because they have been shaped by their surroundings and their experiences. Babies are certainly not evil. Growing up, we see people do things that are “evil”.

_

Are humans inherently good?

Arguments in favour of ‘no’.

Humans tend to only do what they think is best for themselves. The average human only acts for themselves. Humans from birth are inherently selfish; survival is the only mentality they have. Even if it means killing other people then so be it.

_______

_______

Fundamental Nature of Man:

Hobbesian vs. Lockean:

Let me introduce you briefly to John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, and explain in simple terms their opposing beliefs about the nature of man. Then you can choose which camp you want to belong to.

The nature of man according to Hobbes:

According to the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), people are wolves: the bestial nature of man means that we are purely focused on our own interest. We are heedless of others and competitive to the core. We only behave socially and cooperatively out of a sense of self-preservation. Without the intervention of a higher authority there would be permanent war. Thomas Hobbes held the depressing view that man, left to himself, would descend into “a war of all against all.” To prevent us from killing and otherwise hurting each other, government is needed. We grant the government our rights in exchange for its protection. Hobbes thought that we cannot know the difference between good and evil, and cannot achieve peace by our own means. Civil society is thus based on a strong government telling us what to do, and peace is achieved when we do what we are told. Hobbesians, therefore, live in the belief that we are constantly at risk of being hurt by one another. Our assumption is that others are out to get us, and our instinct is to protect ourselves.

The nature of man according to Locke:

John Locke (1632-1704) believed that man is by nature a social animal. For the most part, we are reasonable and tolerant. We tend to live in a state of peace and honour our obligations to each other. Occasional conflicts would arise and so it is important to establish boundaries of ownership. Locke thought that people had an innate sense of right and wrong, even if we disagreed over the specifics from time to time. We are therefore capable of resolving conflicts in a fair and peaceful manner. The state exists to formalise our individual rights in the form of property rights. Lockeans, therefore, are convinced that people are by nature good, and will deal fairly with each other. Our assumption is that others will respect our rights, and our inclination is to seek peaceful co-existence through mutual respect.

_

Also, at the opposite end of the spectrum from Hobbes was the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Rousseau was of the opinion that people have a preference for good: ‘Man is by nature good and happy; it is society which destroys original happiness.’ According to Rousseau it is the corrupting influence of the environment, of society, which incites man to do wrong and therefore makes him unhappy. Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed that man is naturally good and that vice and error are alien to him. This creates a conflict between “nature” and “artifice” in attitudes to society, education and religion. According to Rousseau, nature is man’s state before being influenced by outside forces. At the same time, he asserts: “If man is left… to his own notions and conduct, he would certainly turn out the most preposterous of human beings. The influence of prejudice, authority… would stifle nature in him and substitute nothing.” In other words, human beings need outside intervention to develop their natural propensity for good. “We are born weak, we have need of help, we are born destitute… we have need of assistance; we are born stupid, we have need of understanding.” Man needs to work with nature, not against it. Rousseau says, in his treatise, that man is discontented with anything in its natural state and claims that everything degenerates in his hand… “…he mutilates his dogs, his horses and his slaves; he defaces, he confounds.”

_

The Confucian philosopher Mencius (382-303 BCE) tells the story of how an ordinary person feels if he sees a child fall into a well. Any person, Mencius argues, will feel alarm and distress — not because he hoped for anything from the parents, nor because he feared the anger of anyone because he failed to save the child, nor again because he wanted to enhance his own reputation by this act of modest heroism. It’s simply that, Mencius says, “All men have a mind which cannot bear to see the sufferings of others.” Mencius’s claim is too strong. Whether we think of jihadists cutting off the heads of innocent journalists or soldiers waterboarding helpless prisoners, everywhere we look we see examples of humans not only bearing the sufferings of others, but causing them, even taking pleasure in them. Surely we are both good and evil: it’s hard to imagine an argument or an experiment that would prove that we are wholly one or the other. But that we are both good and evil doesn’t mean we are an equal mix of the two. What Mencius intends is that we are mostly good — that good is our normal state of being and evil is an exceptional one, in much the way health is our normal state of being and sickness the exception. What is our goodness? It seems to be nothing more than the natural tendency towards sympathy, and it looks like it’s not restricted to human beings. A study found that rhesus monkeys would decline to pull a chain that delivered a heaping meal once they figured out that this action simultaneously administered a shock to another rhesus monkey. “These monkeys were literally starving themselves to prevent the shock to the conspecific,” noted one of the researchers. There is also overwhelming evidence that primates experience sympathy for animals outside their own species: Kuni, a bonobo female at Twycross Zoo in England, cared for a wounded starling that fell into her enclosure until it could be removed by the zookeeper. To be good is fundamentally to have other people’s interests in mind, and not—as Mencius is concerned to point out (and after him the philosopher Immanuel Kant)—just because of the good they can do you in return. To be good is to have some genuinely selfless motivations. Of course, circumstances often encourage us to act in selfish and cruel ways: the world is a competitive, rough-and-tumble place, with more scarcity than supply. Yet most of us, when allowed, are naturally inclined toward sympathy and fellow-feeling. As the philosopher R.J. Hankinson says: It’s not just that we do act with sympathy, we are happier when we act that way — and we don’t do it just because it makes us happy. There’s an interesting sort of self-defeating quality about trying to be altruistic for selfish reasons. But what is rare — and looks pathological — is to act purely selfishly. The very oddness, the counter-intuitiveness of the good, suggests a primal source of its existence in us, which in turn explains our perennial insistence upon it. Something in us rebels against the idea of abandoning goodness. Indeed there are many, whether theists or no, who would be deeply offended by the mere suggestion. Here again we see that our goodness wells up from a deep, natural spring.

_

Bruce Bubacz, another philosopher says that every man can be either good or evil: it all depends, to seize on a photographic metaphor, “on the developer and the fixer.” This reminded us of the Cherokee myth that both a good wolf and a bad wolf live in the human heart, always at battle, and the winner is “the one you feed.” Bubacz’s way of looking at it does make sense of cases like the complicity of ordinary Germans in the Holocaust, or the escalations of evil in very recent genocides in places such as Bosnia and Sudan. From the time when humanity was able to believe in it, Utopia has existed as a mere word, thought or principle. It is a place that is hoped for, and is also a society that was and is apparently deemed to be possible, or is it? The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as “an imaginary and indefinitely remote place of ideal perfection in laws, government and social conditions.” It doesn’t exist. It cannot exist because of our nature, our practices, and our imperfections. Since the dawn of man, the world has always been in dissonance. This is because of the differences from one person to another and the uniqueness each individual possesses. For a Utopian society to exist, support and combined focus of individuals who have the same ideals are needed. In order for a perfect society to thrive, its inhabitants must have one idea of perfection. However, there will always be someone who will go astray and believe otherwise; and if a person is able to hold unto individuality, many others will as well.

_

There are two partially true beliefs — both of which claim evidence from evolution.

These two views are:

- People are basically good and just need to be nurtured and freed.

- People are basically bad and need to be controlled to keep from killing each other.

Given the tremendous evidence on both sides, perhaps it might be useful to consider a third thesis that embraces both of them:

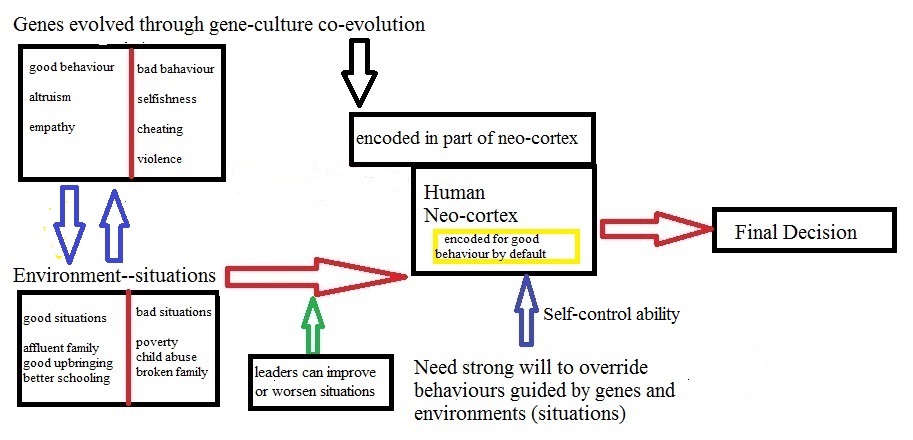

- Human nature is not one thing, neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’ overall. People in general have been genetically endowed by evolution with a wide variety of tendencies and capacities that respond to — but are not necessarily controlled or determined by — their environment. And so we see all sorts of individual and cultural behaviors, providing evidence to defend virtually any assertions about ‘human nature. We might therefore conclude that our challenge at this stage of evolution is to recognize that ‘human nature’ is richly diverse and flexible. Perhaps our task is to use our powers of consciousness, intelligence, and choice to explore the full range of who we are and can be in various circumstances.

______

______

Scientific studies to ascertain whether humans good or bad by their nature:

It’s a question that has repeatedly been asked throughout humanity. For thousands of years, philosophers have debated whether we have a basically good nature that is corrupted by society, or a basically bad nature that is kept in check by society. Psychology has uncovered some evidence which might give the old debate a twist. As long as science has existed people have debated whether humankind is good or evil, and whether this is a matter of nature, or comes from upbringing, education and environment: the nature-nurture debate. Classical economic theories would have us believe that man is egotistical, and focused on satisfying his own needs. If we can choose, for example, between two products of the same quality, then we choose the product with the lowest price, because this is to our advantage. The question as to who is right is not an easy one. Recent research by Kiley Hamlin and colleagues gives us a hint at the answer. They were interested in the question of the extent to which people are naturally able to distinguish right and wrong. Only if people can make this distinction can they determine whether they want to behave accordingly. In order to establish this, research was carried out among young babies. One way of asking about our most fundamental characteristics is to look at babies. Babies’ minds are a wonderful showcase for human nature. Babies are humans with the absolute minimum of cultural influence. Babies have barely any stored information about what is right and what is wrong. They have no friends, no cultural influence, no school or public communication; their innocent minds great for better and more accurate results. Scientists usually communicate with people through speech, but the problem is that babies lack the ability to speak. It would be extremely difficult to know what he/she is thinking when one does not know the language yet. Fortunately, people do not necessarily need to speak to uncover a thought. Infants are known to touch anything they find interesting, hold an object they like, or stare at something that catches their eye. In the study babies aged six months had a large wooden board placed before them. To the left on the board was a picture of a mountain. A wooden figure with two big round eyes then moved towards the mountain. The figure was controlled by the researchers on the other side of the board, out of sight of the baby. The figure tried to climb the mountain, but fell down when it reached half way. This happened again on a second attempt. When the figure climbed the mountain for the third time, another figure was added: the helper or hinderer. The helper also came from the right and pushed the figure to the top. The hinderer came from the left, from the top of the mountain, and pushed the figure down, so that it failed to reach the top for a third time. Both figures were then placed in front of the babies on a tray. The researchers were curious as to which figure the babies would pick up. Would it be the hinderer or the helper? And what happened? In all cases the babies picked up the helper and left the hinderer. Even when the researchers varied the colors and shapes of the helper and hinderer, the results were the same. According to the researchers this is evidence that people are capable of distinguishing right and wrong from a very early age, even before they can speak. We are able to determine what is good and what is harmful for others. Evidently we possess empathy from a young age. But not only that: we also have a tendency to choose the good. However limited the experiment may have been, and however primitive the distinction here between good and evil, this suggests we feel sympathy for what is good. The results they have collected state that even the youngest of minds know what is right and wrong, and an instinct to prefer good over evil. The way to make sense of this result is if infants, with their pre-cultural brains had expectations about how people should act. Not only do they interpret the movement of the shapes as resulting from motivations, but they prefer helping motivations over hindering ones. This doesn’t settle the discussion on natural instinct. A cynic would say that it shows that infants are self-interested and expect others to be the same. Though when born, we naturally have the ability to make sense of the world in terms of motivations, and a basic instinct to prefer friendly intentions over malicious ones. It is on this foundation that adult morality is built and we are born good. The fact that people can tell right from wrong from a young age, and also have a preference for right, does not mean that they always do right. Wrong can sometimes be very attractive.

_

Hamlin’s work complements a similar study published recently by Marco Schmidt and Jessica Summerville. In their study Schmidt and Summervile presented 15 month year old babies two videos: one in which an experimenter distributes an equal share of crackers to two recipients and another in which the experimenter distributes an unequal share of crackers (they also did the same procedure with milk). They measured how the babies looked at the crackers and milk while they were distributed. They found that babies spent more time looking when one recipient got more food than the other. This means, according to “violation of expectancy,” which describes how babies pay more attention to something when it surprises them, that “the infants [expecting] an equal and fair distribution of food… were surprised to see one person given more crackers or milk than the other.”

_

What does this say about us being good or evil? It suggests that babies are born with certain moral capacities and the potential to have a strong moral sense. This does not confirm nor deny that we are inherently… well, anything. The interaction between genes and environment influences our behaviors and personalities; we are not blank slates, in other words. Importantly, what Hamlin’s work is showing is that we are also not moral blank slates.

_

Does altruism really exist?

According to Abraham Lincoln, pure altruism does not exist. One day Lincoln was riding in a coach, in heated discussion with a fellow passenger on the question as to whether helping another is really altruistic. Lincoln argued that helping can always be traced back to one’s own interests, whereas the fellow passenger maintained that there is such a thing as true altruism. Suddenly the men were interrupted by the squeal of a pig trying to rescue her piglets from drowning. Lincoln ordered the coach to stop, jumped out, ran to the stream, grabbed the piglets and set them safely on the bank. Back in the coach his fellow passenger said, ‘Well now, Abe, where’s the selfishness in this incident?’ ‘The reason for my action is a good question,’ Lincoln replied. ‘That was the very essence of selfishness. I should have no peace of mind all day had I gone and left that suffering old sow worrying over those pigs. I did it for my own peace of mind. Do you understand?’ According to Lincoln, self-interest always plays a role, even when we help others. Pure altruism does not exist, only enlightened self-interest. We help one another in order to achieve peace of mind, to soothe our consciences, or to feel good about ourselves. However, people are also spontaneously altruistic by nature. Felix Warneken and Michael Tomasello have shown this to be the case. Their experiment focused on toddlers of 1.5 years. They were confronted with different scenarios in which an unknown adult, the male researcher, had difficulty achieving a goal. The adult accidentally dropped a felt-tip pen on the floor but could not reach to pick it up, and tried and failed to open a cupboard door with his hands full. For every scenario there was a control in which the adult had no difficulty, for instance intentionally throwing the pen on the floor. Each experiment consisted of three phases: for the first ten seconds the adult looked only towards the object, for the next ten seconds he varied between looking at the object and at the child and in the last ten seconds the adult talked about the problem and continued to look from the object to the child and back. There was no benefit to the child in helping: no reward was on offer in return for help. Furthermore, no appreciation was shown. What was the outcome? 92 percent of the children helped at least once, whereas the figure was considerably lower in the control scenarios. In the scenario with the pen alone two-thirds of the children helped, compared to only a quarter in the control. Interestingly in almost all situations in which the toddler helped (84 percent), this happened in the first ten seconds, without the adult looking at the toddler for help or asking for help. According to Warneken and Tomasello, their research shows that even very young children have a natural inclination to help others solve their problems, even when the other person is a stranger and there is nothing to be gained. They conclude that this is evidence of the existence of pure altruism. Helpfulness is apparently in our genes, at least for most people. Not only are we able to tell when others need help at an early age, we are also prepared to help, even if the help offered in the experimental scenario did not take much effort and the children did not have to sacrifice much. Daniel Batson and his team have carried out a great deal of research into the situations in which adults are altruistic. Their experiments show that people help others when they feel empathy for them, even when the costs are greater than the rewards. This empathy is generated when people see that the other needs help, when they value the well-being of the person in need, and when they are able to put themselves in the position of the other and to understand what the help means for them.

_

For centuries many philosophers, as well as most individuals, have pondered on the question what is good and what is evil. More-so philosophers of all ages have also stumbled upon a more in depth question which is if the intuitive knowledge of man’s nature is good, or if it is evil. A new set of studies provides compelling data allowing us to analyze human nature not through a philosopher’s kaleidoscope or a TV producer’s camera, but through the clear lens of science. These studies were carried out by a diverse group of researchers from Harvard and Yale—a developmental psychologist with a background in evolutionary game theory, a moral philosopher-turned-psychologist, and a biologist-cum-mathematician—interested in the same essential question: whether our automatic impulse—our first instinct—is to act selfishly or cooperatively. This focus on first instincts stems from the dual process framework of decision-making, which explains decisions (and behavior) in terms of two mechanisms: intuition and reflection. Intuition is often automatic and effortless, leading to actions that occur without insight into the reasons behind them. Reflection, on the other hand, is all about conscious thought—identifying possible behaviors, weighing the costs and benefits of likely outcomes, and rationally deciding on a course of action. With this dual process framework in mind, we can boil the complexities of basic human nature down to a simple question: which behavior—selfishness or cooperation—is intuitive, and which is the product of rational reflection? In other words, do we cooperate when we overcome our intuitive selfishness with rational self-control, or do we act selfishly when we override our intuitive cooperative impulses with rational self-interest? To answer this question, the researchers first took advantage of a reliable difference between intuition and reflection: intuitive processes operate quickly, whereas reflective processes operate relatively slowly. Whichever behavioral tendency—selfishness or cooperation—predominates when people act quickly is likely to be the intuitive response; it is the response most likely to be aligned with basic human nature.

_

The experimenters first examined potential links between processing speed, selfishness, and cooperation by using 2 experimental paradigms (the “prisoner’s dilemma” and a “public goods game”), 5 studies, and a total of 834 participants gathered from both undergraduate campuses and a nationwide sample. Each paradigm consisted of group-based financial decision-making tasks and required participants to choose between acting selfishly—opting to maximize individual benefits at the cost of the group—or cooperatively—opting to maximize group benefits at the cost of the individual. The results were striking: in every single study, faster—that is, more intuitive—decisions were associated with higher levels of cooperation, whereas slower—that is, more reflective—decisions were associated with higher levels of selfishness. These results suggest that our first impulse is to cooperate—that Hobbes was wrong, and that we are fundamentally “good” creatures after all. The researchers followed up these correlational studies with a set of experiments in which they directly manipulated both this apparent influence on the tendency to cooperate—processing speed—and the cognitive mechanism thought to be associated with this influence—intuitive, as opposed to reflective, decision-making. In the first of these studies, researchers gathered 891 participants (211 undergraduates and 680 participants from a nationwide sample) and had them play a public goods game with one key twist: these participants were forced to make their decisions either quickly (within 10 seconds) or slowly (after at least 10 seconds had passed). In the second, researchers had 343 participants from a nationwide sample play a public goods game after they had been primed to use either intuitive or reflective reasoning. Both studies showed the same pattern—whether people were forced to use intuition (by acting under time constraints) or simply encouraged to do so (through priming), they gave significantly more money to the common good than did participants who relied on reflection to make their choices. This again suggests that our intuitive impulse is to cooperate with others. Taken together, these studies—7 total experiments, using a whopping 2,068 participants—suggest that we are not intuitively selfish creatures. But does this mean that we our naturally cooperative? Or could it be that cooperation is our first instinct simply because it is rewarded? After all, we live in a world where it pays to play well with others: cooperating helps us make friends, gain social capital, and find social success in a wide range of domains. As one way of addressing this possibility, the experimenters carried out yet another study. In this study, they asked 341 participants from a nationwide sample about their daily interactions—specifically, whether or not these interactions were mainly cooperative; they found that the relationship between processing speed (that is, intuition) and cooperation only existed for those who reported having primarily cooperative interactions in daily life. This suggests that cooperation is the intuitive response only for those who routinely engage in interactions where this behavior is rewarded—that human “goodness” may result from the acquisition of a regularly rewarded trait.

_

Throughout the ages, people have wondered about the basic state of human nature—whether we are good or bad, cooperative or selfish. This question—one that is central to who we are—has been tackled by theologians and philosophers, presented to the public eye by television programs, and dominated the sleepless nights of both guilt-stricken villains and bewildered victims; now, it has also been addressed by scientific research. Although no single set of studies can provide a definitive answer—no matter how many experiments were conducted or participants were involved—this research suggests that our intuitive responses, or first instincts, tend to lead to cooperation rather than selfishness. Although this evidence does not definitely solve the puzzle of human nature, it does give us evidence we may use to solve this puzzle for ourselves—and our solutions will likely vary according to how we define “human nature.” If human nature is something we must be born with, then we may be neither good nor bad, cooperative nor selfish. But if human nature is simply the way we tend to act based on our intuitive and automatic impulses, then it seems that we are an overwhelmingly cooperative species, willing to give for the good of the group even when it comes at our own personal expense.

_______

_______

What is evil?

The obvious thing to say about evil is that it is the opposite of good. However, this definition is too imprecise to be of much use. “The Free Dictionary” proposes; that which is “morally bad or wrong; wicked”. Hence something that is immoral, but also wicked. Wicked is defined as “evil by nature” or “malicious”. “The WordNet Search” at Princeton University’s web pages has a similar definition: “morally objectionable behaviour” and “morally bad or wrong”. Clearly, if something is evil it opposes morality. But whose morality? This is where the problem lies. Is a person evil if he or she acts according to his or hers morality? “Wikipedia“offers the explanation that something is evil if it violates “the most basic moral or ethical standards prescribed by a society, philosophy, or religion“. Further, it says that since different societies have different morals, evil is not a fixed thing. So, if this definition has some validity, it is the society’s morality, and not the individual’s, that determines if something is evil. However, both “The Free Dictionary” and “The WordNet Search’s” definitions have a second significant part. The focus lies on the consequences of an action, not the intention. It seems that, to be evil, an action must, at least, be wrong. The Free Dictionary’s second definition of evil is that which is “causing ruin, injury, or pain; harmful”. Furthermore, the WordNet Search’s is “that which causes harm or destruction or misfortune”. Both focus on the consequences of an action. If it causes injury, pain or harm, it is considered evil. As a rule, by “evil” we mean acts that are profoundly anti-human or anti-social, such as rape, torture, killing, etc. Evil is intentionally behaving — or causing others to act – in ways that demean, dehumanize, harm, destroy, or kill innocent people. This behaviorally-focused definition makes evil responsible for purposeful, motivated actions that have a range of negative consequences to other people. It excludes accidental or unintended harmful outcomes, as well as the broader, generic forms of institutional evil, such as poverty, prejudice or destruction of the environment by agents of corporate greed. But it does include corporate responsibility for marketing and selling products with known disease-causing, death-dealing properties, such as cigarette manufacturers, or other drug dealers. It also extends beyond the proximal agent of aggression, as studied in research on interpersonal violence, to encompass those in distal positions of authority whose orders or plans are carried out by functionaries. This is true of military commanders and national leaders, such as Hilter, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Idi Amin, and others who history has identified as tyrants for their complicity in the deaths of untold millions of innocent people. We live in a world cloaked in the evils of civil and international wars, of terrorism — home-grown and exported — of homicides, of rapes, of domestic and child abuse, and more forms of devastation. The same human mind that creates the most beautiful works of art and extraordinary marvels of technology is equally responsible for the perversion of its own perfection. This most dynamic organ in the universe has been a seemingly endless source for creating ever more vile torture chambers and instruments of horror in earlier centuries, the “bestial machinery” unleashed on Chinese citizens by Japanese soldiers in their rape of Nanking, and the recent demonstration of “creative evil” of the destruction of the World Trade Center by weaponizing commercial airlines. We continue to ask why? Why and how is it possible for such deeds to continue to occur? How can the unimaginable become so readily imagined? And these are the same questions that have been asked by generations before ours. The human mind is so marvellous that it can adapt to virtually any known environmental circumstance in order to survive, to create, and to destroy as necessary. The vast majority of human cultures have been observed doing evil things, and otherwise ordinary people from contemporary civilisations have been observed doing these things under certain conditions. This suggests it is in our nature to be evil (in this sense), but also that it is not inevitable that we manifest this aspect of our nature.

_

The Evil of Inaction:

Perpetrators, collaborators, bystanders, victims: we can be clear about three of these categories. The bystander, however, is the fulcrum. If there are enough notable exceptions, then protest reaches a critical mass. We don’t usually think of history as being shaped by silence, but, as English philosopher Edmund Burke said, ‘The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.’ Our usual take on evil focuses on violent, destructive actions, but non-action can also become a form of evil, when helping, dissent and disobedience are called for. Social psychologists heeded the alarm when the infamous Kitty Genovese case made national headlines. As she was being stalked, stabbed and eventually murdered, 39 people in a housing complex heard her screams and did nothing to help. It seemed obvious that this was a prime example of the callousness of New Yorkers, as many media accounts reported. A counter to this dispositional analysis came in the form of a series of classic studies by Bibb Latan and John Darley (1970) on bystander intervention. One key finding was that people are less likely to help when they are in a group, when they perceive others are available who could help, than when those people are alone. The presence of others diffuses the sense of personal responsibility of any individual. A research study found that you should not be a victim in distress when people are late and in a hurry, because 90 percent of them are likely to pass you by, giving you no help at all! The more time the people believed they had, the more likely they were to stop and help. So the situational variable of time press accounted for the major variance in helping, without any need to resort to dispositional explanations about people being callous or cynical or indifferent.

_

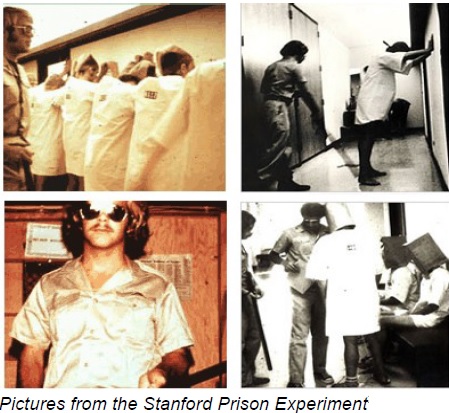

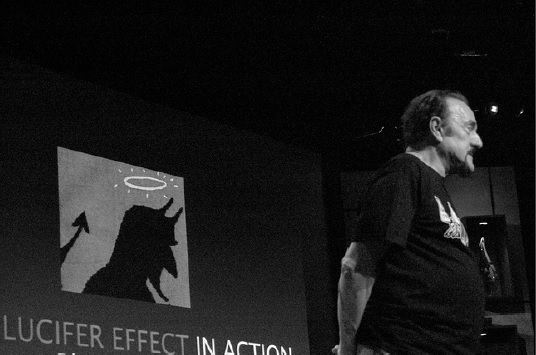

“The line between good and evil is permeable,” said psychologist Philip Zimbardo, “and almost anyone can be induced to cross it when pressured by situational forces. …I argue that we all have the capacity for love and evil—to be Mother Theresa, to be Hitler or Saddam Hussein. It’s the situation that brings that out.” As Zimbardo and other social scientists have shown in a range of experiments, actions we deem evil – cheating, lying, stealing, and worse – don’t spring from people’s character, but the situations they find themselves in. When people have an ideology to justify their actions, they’ll do bad things. Philip Zimbardo, professor emeritus of psychology at Stanford University, argues that people do evil things when they have an ideology — or system of ideals — to lean on. “All evil begins with a big ideology,” Zimbardo said. “What is the evil ideology about the Iraq war? National security. National security is the ideology that is used to justify torture in Brazil. You always begin with this big, good thing because once you have the big ideology then it’s going to justify all the action.”

_

What makes us evil?

Research has uncovered many answers to this question: Evil can be fostered by dehumanization, diffusion of responsibility, obedience to authority, unjust systems, group pressure, moral disengagement, and anonymity, to name a few. We are all born with tremendous capacity to be anything, and we get shaped by our circumstances—by the family or the culture or the time period in which we happen to grow up, which are accidents of birth; whether we grow up in a war zone versus peace; if we grow up in poverty rather than prosperity. George Bernard Shaw captured this point in the preface to his great play “Major Barbara”: “Every reasonable man and woman is a potential scoundrel and a potential good citizen. What a man is depends upon his character what’s inside. What he does and what we think of what he does depends on upon his circumstances.” So each of us may possess the capacity to do terrible things. But we also possess an inner hero; if stirred to action, that inner hero is capable of performing tremendous goodness for others.

_

God versus devil:

“Who is responsible for evil in the world, given that there is an all-powerful, omniscient God who is also all-Good?” That conundrum began the intellectual scaffolding of the Inquisition in the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe. As revealed in Malleus Maleficarum, the handbook of the German Inquisitors from the Roman Catholic Church, the inquiry concluded that the Devil was the source of all evil. However, these theologians argued the Devil works his evil through intermediaries, lesser demons and of course, human witches. So the hunt for evil focused on those marginalized people who looked or acted differently from ordinary people, who might qualify under rigorous examination of conscience, and torture, to expose them as witches, and then put to death. They were mostly women who could readily be exploited without sources of defence, especially when they had resources that could be confiscated. An analysis of this legacy of institutionalized violence against women is detailed by historian Anne Barstow (1994) in Witchcraze. Paradoxically, this early effort of the Inquisition to understand the origins of evil and develop interventions to cope with evil instead created new forms of evil that fulfilled all facets of definition of evil. But it exemplifies the notion of simplifying the complex problem of widespread evil by identifying individuals who might be the guilty parties, and then making them pay for their evil deeds.

_

Psychodynamic theory, as well as most traditional psychiatry, also locates the source of individual violence and anti-social behavior within the psyches of disturbed people, often tracing it back to early roots in unresolved infantile conflicts. Like genetic views of pathology, such psychological approaches seek to link behaviors society judges as pathological to pathological origins — defective genes, “bad seeds,” or pre-morbid personality structures. But the same violent outcomes can be generated by very different types of people, who give no hint of evil impulses. Psychologists interviewed and tested 19 inmates in California prisons who had all recently been convicted of homicide. Half of these killers had a long history of violence, showing lack of impulse control, were decidedly masculine in sexual identity, and generally extroverted. The other ten murderers were totally different. They had never committed any criminal offense prior to the current homicide — their murders were totally unexpected given their mild manner and gentle disposition. Their problem was excessive impulse control that inhibited their expression of any feelings. Their sexual identity was feminine or androgynous, and the majority was shy. These “Shy Sudden Murderers” killed just as violently as did the habitual criminals, and their victims died just as surely, but it would have been impossible to predict this outcome from any prior knowledge of their personalities that were so different from the more obvious habitual criminals. Human nature proves to be both good and evil because they’re dependent on strength despite individual experiences, showing that a person’s destiny can only be decided by themselves. Once an individual lets either good or evil take over, it will become extremely difficult to reverse. The great philosopher Socrates said “the unexamined life is not worth living.” We are forced to examine our lives at some point by the pressing questions of our own nature. The answers to questions of our goodness or badness are answered every day by our actions and the actions of those around us. One doesn’t have to look far to see both the best and the worst of who we are as a species.

________

________

Genocide by ordinary people:

The last century has been nicknamed the “age of genocide”. It started with the killing of 80 percent of the Heroro population in Namibia in 1905–07, followed by the Armenian holocaust and the Greek genocide where the Ottoman government was the culprit, the extermination of Jews by the Nazis, the persecutions of Germans by the hands of the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, the Rwandan genocide, up to the more recent South African farm attacks. These atrocities are carried out by ordinary people. One day they will carry out gruesome acts of pillage and plunder, and the next day be ever so nice to their family, pets, and neighbours.

_

Around six million people were killed in the Holocaust, the Nazis’ systematic attempt to exterminate the Jewish people. Jews from across Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe were rounded up, and either transported to extermination camps where they were gassed, shot locally, or starved and abused in ghettos and labour camps until they died. This was murder on an industrial scale, and it took an industrial process to do it. From the office workers who planned and oversaw the logistics, to the railway staff who ran the trains, to the community policemen who guarded the streets, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people were part of this attempted genocide. It can be hard for us to even try to understand how this was possible. We might assume that ordinary citizens were so terrified of retribution from the vicious Nazi regime that they reluctantly went along with it. But the truth is far more disturbing than that. In fact, thousands of people, who had lived side by side with their Jewish neighbours for generations, were quite willing to turn on them and become part of a programme of mass murder. After the war, many of the people who played their part in the Holocaust said that they had no choice but to follow orders. Yet historians and German prosecutors have failed to find a single case of any person being threatened with death or imprisonment for refusing to take part. In fact even when given a choice to opt out, ordinary people went on to commit atrocities.

_

The 2002 Gujarat riots was a three-day period of inter-communal violence in the Indian state of Gujarat. The burning of a train in Godhra on 27 February 2002, which caused the deaths of 58 Hindu pilgrims karsevaks returning from Ayodhya, is believed to have triggered the violence. According to official figures, the riots resulted in the deaths of 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus; 2,500 people were injured non-fatally, and 223 more were reported missing. Other sources estimate that over 2000 people died. There were instances of rape, children being burned alive, and widespread looting and destruction of property. 273 dargahs, 241 mosques, 19 temples, and 3 churches had been either destroyed or damaged. It is estimated that Muslim property losses were, “100,000 houses, 1,100 hotels, 15,000 businesses, 3,000 handcarts and 5,000 vehicles destroyed.” In total 27,780 persons were arrested, either for rioting or as a preventative measure. Most of them were ordinary people and not hardened criminals. While officially classified as a communal riot, the events of 2002 have been described as a pogrom by many scholars, and other independent observers have stated that these events had met the “legal definition of genocide”. Similarly horrific example might have surfaced from Babi Yar or Dili, Srebrenica or Rwanda. Genocides in vastly different cultures share this reality: Scores of innocent people die at the brutal hands of ordinary people.

_

James Waller, a professor of psychology at Whitworth College in Spokane, Wash., suggests that perpetrators of genocide — those who commit what Waller calls “extraordinary human evil” — aren’t just ideologically committed sociopaths or else passive weaklings who’ve been forced to pull the trigger. And contrary to what historians such as Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, the author of “Hitler’s Willing Executioners,” contend, there isn’t a far-reaching cultural explanation for why one ethnic, religious or political group decides to slaughter another. Instead, according to Waller, complex forces in human nature make all of us capable of committing acts of genocide. Even healers become killers, even women can be just as brutal as men, and we should expect more cases of genocide in the future. In the range of human evil, some of it is very ordinary — gossip, slander, the petty evil we perpetrate every day. But at some level, it takes a qualitative jump and evil becomes rather extraordinary. This extraordinary evil is genocide and mass killing — the murder of innocent men, women and children outside of military conflict. It’s extraordinary in the sense that a political, social or religious group has come to power or take law in their hand, and they decide to exterminate another group of people living in their midst. The perpetrators of genocide and mass killing are not lunatics or insane but ordinary people with extraordinary evil. We know that 6 million Jews died in the Holocaust, but very seldom do we step back and ask the question: How many people does it take to kill 6 million people? We know that 800,000 Rwandans died in 100 days, but again, how many people does it take to kill 800,000 people? A lot of ordinary people are recruited to do genocide or massacre. And in the Holocaust you had incidences of this, too — read Jan Gross’ book, entitled “Neighbors,” about a small village in Poland named Jedwabne where the Catholic half of the village killed the Jewish half simply because they were given permission to do so. You realize how thin this veneer of civilization is that we put up. We say we live as neighbors and in a community, but when something happens structurally that says now you have permission to persecute, to take from, to even kill people that you’ve lived with for years, the relative ease with which people can do that is incredible. Robert J. Lifton said it very well in one of his interviews with a Nazi doctor. The doctor said, “If a patient comes to me with a gangrenous appendix, I have to remove that appendix; I take out a part of their body to save the larger body.” The doctor saw the Jews as the gangrenous appendix in Germany, so he could kill Jews because it was part of healing the larger national body of Germans.

_

Ordinary men murder ordinary men, women, and children:

One of the clearest illustrations of how ordinary people can be transformed into engaging in evil deeds that are alien to their past history and to their moral development comes from the analysis of British historian, Christopher Browning. He recounts in Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (1993) that in March, 1942 about 80 percent of all victims of the Holocaust were still alive, but a mere 11 months later about 80 percent were dead. In this short period of time, the Endlösung (Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’) was energized by means of an intense wave of mass mobile murder squads in Poland. This genocide required mobilization of a large-scale killing machine at the same time as able-bodied soldiers were needed on the Russian front. Since most Polish Jews lived in small towns and not the large cities, the question that Browning raised about the German high command was “where had they found the manpower during this pivotal year of the war for such an astounding logistical achievement in mass murder?” His answer came from archives of Nazi war crimes, in the form of the activities of Reserve Battalion 101, a unit of about 500 men from Hamburg, Germany. They were elderly, family men too old to be drafted into the army, from working-class and lower middle-class backgrounds, with no military police experience, just raw recruits sent to Poland without warning of, or any training in, their secret mission — the total extermination of all Jews living in the remote villages of Poland. In just 4 months they had shot to death at point blank range at least 38,000 Jews and had another 45,000 deported to the concentration camp at Treblinka. Initially, their commander told them that this was a difficult mission which must be obeyed by the battalion but any individual could refuse to execute these men, women and children. Records indicate that at first about half the men refused and let the others do the mass murder. But over time, social modelling processes took their toll, as did any guilt-induced persuasion by buddies who did the killing, until at the end up to 90 percent of the men in Battalion 101 were involved in the shootings, even proudly taking photographs of their up-close and personal killing of Jews. Browning makes clear that there was no special selection of these men, only that they were as “ordinary” as can be imagined — until they were put into a situation in which they had “official” permission and encouragement to act sadistically and brutishly against those arbitrarily labelled as the “enemy.”

_______

_______

Ethics are compromised in pursuit of Career:

Ethics can be dangerous to your career. The danger may come not from your own ethics but from the ethics of people around you and the organization of which you are a part. At work, you may be called upon to do things that turn out to be unethical or even illegal. What should you do if that occurs? According to the old adage, “The best defense is a good offense.” And the best defense against involvement in wrongdoing is being prepared for organizational challenges that will inevitably test your personal values, moral beliefs, and commitment to doing the right thing. A study of more than 1,000 Columbia Business School graduates found that 40 percent had been rewarded for taking some action they considered to be “ethically troubling,” and 31 percent of those who refused to act in ways they considered to be unethical believed that they were penalized for their choice, compared to less than 20 percent who felt they had been rewarded. Ethics can be dangerous to your career if you have not been trained to identify and analyze ethical problems and to resolve them effectively. Ethics can also be dangerous to your career if you work in an organization that does not support ethical behavior or, worse, encourages misconduct. Finally, we should recognize that anyone can get caught up in unethical conduct under the right circumstances. Organizational forces are very strong, and we humans have many psychological weaknesses that make us vulnerable to wrongdoing. Steps can be taken to improve both organizations and the individuals in them, and we should take those steps. But the dangers cannot be eliminated entirely.

_

Conflict of interest: